Altair

From Handwiki

From Handwiki  | |

| Observation data Equinox J2000.0]] (ICRS) | |

|---|---|

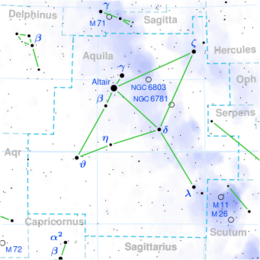

| Constellation | Aquila |

| Pronunciation | /ˈæltɛər/, /ˈæltaɪər/[1][2] |

| Right ascension | 19h 50m 46.99855s[3] |

| Declination | +08° 52′ 05.9563″[3] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 0.76[4] |

| Characteristics | |

| Evolutionary stage | Main sequence |

| Spectral type | A7Vn[5] |

| U−B color index | +0.09[4] |

| B−V color index | +0.22[4] |

| V−R color index | +0.14[4] |

| R−I color index | +0.13[4] |

| Variable type | Delta Scuti[6] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | −26.1±0.9[7] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: +536.23[3] mas/yr Dec.: +385.29[3] mas/yr |

| Parallax (π) | 194.95 ± 0.57[3] mas |

| Distance | 16.73 ± 0.05 ly (5.13 ± 0.01 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 2.22[6] |

| Details | |

| Mass | 1.86±0.03[8] M☉ |

| Radius | 1.57 – 2.01[8][nb 1] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 10.6[9] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 4.29[10] cgs |

| Temperature | 6,860 – 8,621[8][nb 1] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | −0.2[11] dex |

| Rotation | 7.77 hours[9] |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 242[8] km/s |

| Age | 100[8] Myr |

| Other designations | |

Atair, α Aquilae, α Aql, Alpha Aquilae, Alpha Aql, 53 Aquilae, 53 Aql, BD+08°4236, FK5 745, GJ 768, HD 187642, HIP 97649, HR 7557, SAO 125122, WDS 19508+0852A, LFT 1499, LHS 3490, LTT 15795, NLTT 48314[7][12][13] | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

Altair is the brightest star in the constellation of Aquila and the twelfth-brightest star in the night sky. It has the Bayer designation Alpha Aquilae, which is Latinised from α Aquilae and abbreviated Alpha Aql or α Aql. Altair is an A-type main-sequence star with an apparent visual magnitude of 0.77 and is one of the vertices of the Summer Triangle asterism; the other two vertices are marked by Deneb and Vega.[7][14][15] It is located at a distance of 16.7 light-years (5.1 parsecs) from the Sun.[16]Template:Citation page Altair is currently in the G-cloud—a nearby interstellar cloud, an accumulation of gas and dust.[17][18]

Altair rotates rapidly, with a velocity at the equator of approximately 286 km/s.[nb 2][11] This is a significant fraction of the star's estimated breakup speed of 400 km/s.[19] A study with the Palomar Testbed Interferometer revealed that Altair is not spherical, but is flattened at the poles due to its high rate of rotation.[20] Other interferometric studies with multiple telescopes, operating in the infrared, have imaged and confirmed this phenomenon.[11]

Nomenclature

α Aquilae (Latinised to Alpha Aquilae) is the star's Bayer designation. The traditional name Altair has been used since medieval times. It is an abbreviation of the Arabic phrase النسر الطائر Al-Nisr Al-Ṭa'ir, "the flying eagle".[21]

In 2016, the International Astronomical Union organized a Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)[22] to catalog and standardize proper names for stars. The WGSN's first bulletin of July 2016[23] included a table of the first two batches of names approved by the WGSN, which included Altair for this star. It is now so entered in the IAU Catalog of Star Names.[24]

Physical characteristics

Along with β Aquilae and γ Aquilae, Altair forms the well-known line of stars sometimes referred to as the Family of Aquila or Shaft of Aquila.[16]Template:Citation page

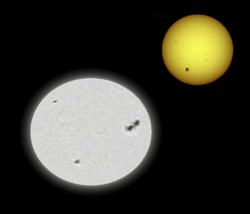

Altair is a type-A main-sequence star with about 1.8 times the mass of the Sun and 11 times its luminosity.[11][9] It is thought to be a young star close to the zero age main sequence at about 100 million years old, although previous estimates gave an age closer to one billion years old.[8] Altair rotates rapidly, with a rotational period of under eight hours;[8] for comparison, the equator of the Sun makes a complete rotation in a little more than 25 days, but Altair's rotation is similar to, and slightly faster than, those of Jupiter and Saturn. Like those two planets, its rapid rotation causes the star to be oblate; its equatorial diameter is over 20 percent greater than its polar diameter.[11]

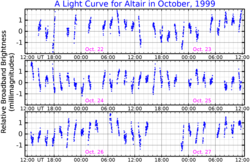

Satellite measurements made in 1999 with the Wide Field Infrared Explorer showed that the brightness of Altair fluctuates slightly, varying by just a few thousandths of a magnitude with several different periods less than 2 hours.[6] As a result, it was identified in 2005 as a Delta Scuti variable star. Its light curve can be approximated by adding together a number of sine waves, with periods that range between 0.8 and 1.5 hours.[6] It is a weak source of coronal X-ray emission, with the most active sources of emission being located near the star's equator. This activity may be due to convection cells forming at the cooler equator.[19]

Rotational effects

.jpg)

The angular diameter of Altair was measured interferometrically by R. Hanbury Brown and his co-workers at Narrabri Observatory in the 1960s. They found a diameter of 3 milliarcseconds.[25] Although Hanbury Brown et al. realized that Altair would be rotationally flattened, they had insufficient data to experimentally observe its oblateness. Later, using infrared interferometric measurements made by the Palomar Testbed Interferometer in 1999 and 2000, Altair was found to be flattened. This work was published by G. T. van Belle, David R. Ciardi and their co-authors in 2001.[20]

Theory predicts that, owing to Altair's rapid rotation, its surface gravity and effective temperature should be lower at the equator, making the equator less luminous than the poles. This phenomenon, known as gravity darkening or the von Zeipel effect, was confirmed for Altair by measurements made by the Navy Precision Optical Interferometer in 2001, and analyzed by Ohishi et al. (2004) and Peterson et al. (2006).[9][26] Also, A. Domiciano de Souza et al. (2005) verified gravity darkening using the measurements made by the Palomar and Navy interferometers, together with new measurements made by the VINCI instrument at the VLTI.[27]

Altair is one of the few stars for which a direct image has been obtained.[28] In 2006 and 2007, J. D. Monnier and his coworkers produced an image of Altair's surface from 2006 infrared observations made with the MIRC instrument on the CHARA array interferometer; this was the first time the surface of any main-sequence star, apart from the Sun, had been imaged.[28] The false-color image was published in 2007. The equatorial radius of the star was estimated to be 2.03 solar radii, and the polar radius 1.63 solar radii—a 25% increase of the stellar radius from pole to equator.[11] The polar axis is inclined by about 60° to the line of sight from the Earth.[19]

Etymology, mythology and culture

The term Al Nesr Al Tair appeared in Al Achsasi al Mouakket's catalogue, which was translated into Latin as Vultur Volans.[29] This name was applied by the Arabs to the asterism of Altair, β Aquilae and γ Aquilae and probably goes back to the ancient Babylonians and Sumerians, who called Altair "the eagle star".[2]Template:Citation page The spelling Atair has also been used.[30] Medieval astrolabes of England and Western Europe depicted Altair and Vega as birds.[31]

The Koori people of Victoria also knew Altair as Bunjil, the wedge-tailed eagle, and β and γ Aquilae are his two wives the black swans. The people of the Murray River knew the star as Totyerguil.[32]Template:Citation page The Murray River was formed when Totyerguil the hunter speared Otjout, a giant Murray cod, who, when wounded, churned a channel across southern Australia before entering the sky as the constellation Delphinus.[32]Template:Citation page

In Chinese belief, the asterism consisting of Altair, β Aquilae and γ Aquilae is known as Hé Gǔ (河鼓; lit. "river drum").[30] The Chinese name for Altair is thus Hé Gǔ èr (河鼓二; lit. "river drum two", meaning the "second star of the drum at the river").[33] However, Altair is better known by its other names: Qiān Niú Xīng (牵牛星 / 牽牛星) or Niú Láng Xīng (牛郎星), translated as the cowherd star.[34][35] These names are an allusion to a love story, The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl, in which Niulang (represented by Altair) and his two children (represented by β Aquilae and γ Aquilae) are separated from respectively their wife and mother Zhinu (represented by Vega) by the Milky Way. They are only permitted to meet once a year, when magpies form a bridge to allow them to cross the Milky Way.[35][36]

The people of Micronesia called Altair Mai-lapa, meaning "big/old breadfruit", while the Māori people called this star Poutu-te-rangi, meaning "pillar of heaven".[37]

In Western astrology, the star was ill-omened, portending danger from reptiles.[30]

This star is one of the asterisms used by Bugis sailors for navigation, called bintoéng timoro, meaning "eastern star".[38]

A group of Japan ese scientists sent a radio signal to Altair in 1983 with the hopes of contacting extraterrestrial life.[39]

NASA announced Altair as the name of the Lunar Surface Access Module (LSAM) on December 13, 2007.[40] The Russian-made Beriev Be-200 Altair seaplane is also named after the star.[41]

Visual companions

The bright primary star has the multiple star designation WDS 19508+0852A and has several faint visual companion stars, WDS 19508+0852B, C, D, E, F and G.[13] All are much more distant than Altair and not physically associated.[42]

| Component | Primary | Right ascension (α) Equinox J2000.0 |

Declination (δ) Equinox J2000.0 |

Epoch of observed separation |

Angular distance from primary |

Position angle (relative to primary) |

Apparent magnitude (V) |

Database reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | A | 19h 50m 40.5s | +08° 52′ 13″[43] | 2015 | 195.8″ | 286° | 9.8 | SIMBAD |

| C | A | 19h 51m 00.8s | +08° 50′ 58″[44] | 2015 | 186.4″ | 110° | 10.3 | SIMBAD |

| D | A | 2015 | 26.8″ | 105° | 11.9 | |||

| E | A | 2015 | 157.3″ | 354° | 11.0 | |||

| F | A | 19h 51m 02.0s | +08° 55′ 33″ | 2015 | 292.4″ | 48° | 10.3 | SIMBAD |

| G | A | 2015 | 185.1″ | 121° | 13.0 |

See also

- Lists of stars

- List of brightest stars

- List of nearest bright stars

- Historical brightest stars

- List of most luminous stars

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Owing to its rapid rotation, Altair's radius is larger at its equator than at its poles; it is also cooler at the equator than at the poles.

- ↑ From values of v sin i and i in the second column of Table 1, Monnier et al. 2007.

References

- ↑ "Altair: definition of Altair in Oxford dictionary (American English)". http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/american_english/altair.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kunitzsch, Paul; Smart, Tim (2006). A Dictionary of Modern star Names: A Short Guide to 254 Star Names and Their Derivations (2nd rev. ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Sky Pub. ISBN 978-1-931559-44-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 van Leeuwen, F. (November 2007), "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction", Astronomy and Astrophysics 474 (2): 653–664, doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357, Bibcode: 2007A&A...474..653V

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Ducati, J. R. (2002). "VizieR Online Data Catalog: Catalogue of Stellar Photometry in Johnson's 11-color system". CDS/ADC Collection of Electronic Catalogues 2237: 0. Bibcode: 2002yCat.2237....0D.

- ↑ Gray, R. O. et al. (2003), "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: Spectroscopy of Stars Earlier than M0 within 40 Parsecs: The Northern Sample. I", The Astronomical Journal 126 (4): 2048, doi:10.1086/378365, Bibcode: 2003AJ....126.2048G.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Buzasi, D. L.; Bruntt, H.; Bedding, T. R.; Retter, A.; Kjeldsen, H.; Preston, H. L.; Mandeville, W. J.; Suarez, J. C. et al. (February 2005). "Altair: The Brightest δ Scuti Star" (in en). The Astrophysical Journal 619 (2): 1072–1076. doi:10.1086/426704. ISSN 0004-637X. Bibcode: 2005ApJ...619.1072B.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 NAME ALTAIR -- Variable Star of delta Sct type, database entry, SIMBAD. Accessed on line November 25, 2008.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Bouchaud, K.; Domiciano De Souza, A.; Rieutord, M.; Reese, D. R.; Kervella, P. (2020). "A realistic two-dimensional model of Altair". Astronomy and Astrophysics 633: A78. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201936830. Bibcode: 2020A&A...633A..78B.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Peterson, D. M.; Hummel, C. A.; Pauls, T. A. et al. (2006). "Resolving the Effects of Rotation in Altair with Long-Baseline Interferometry". The Astrophysical Journal 636 (2): 1087–1097. doi:10.1086/497981. Bibcode: 2006ApJ...636.1087P. See Table 2 for stellar parameters.

- ↑ Malagnini, M. L.; Morossi, C. (November 1990), "Accurate absolute luminosities, effective temperatures, radii, masses and surface gravities for a selected sample of field stars", Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series 85 (3): 1015–1019, Bibcode: 1990A&AS...85.1015M

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Monnier, J. D.; Zhao, M; Pedretti, E; Thureau, N; Ireland, M; Muirhead, P; Berger, J. P.; Millan-Gabet, R et al. (2007). "Imaging the surface of Altair". Science 317 (5836): 342–345. doi:10.1126/science.1143205. PMID 17540860. Bibcode: 2007Sci...317..342M. See second column of Table 1 for stellar parameters.

- ↑ HR 7557, database entry, The Bright Star Catalogue, 5th Revised Ed. (Preliminary Version), D. Hoffleit and W. H. Warren, Jr., CDS ID V/50. Accessed on line November 25, 2008.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Entry 19508+0852, The Washington Double Star Catalog , United States Naval Observatory. Accessed online November 25, 2008.

- ↑ David Darling. "Altair". http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/A/Altair.html.

- ↑ Darling, David. "Summer Triangle". http://www.daviddarling.info/encyclopedia/S/Summer_Triangle.html.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Hoboken, Fred Schaaf (2008). The brightest stars : discovering the universe through the sky's most brilliant stars. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. ISBN 978-0-471-70410-2. OCLC 440257051.

- ↑ "Our Local Galactic Neighborhood". NASA. http://interstellar.jpl.nasa.gov/interstellar/probe/introduction/neighborhood.html.

- ↑ Gilster, Paul (2010-09-01). "Into the Interstellar Void" (in en-US). Centauri Dreams. http://www.centauri-dreams.org/?p=14203.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Robrade, J.; Schmitt, J. H. M. M. (April 2009), "Altair - the "hottest" magnetically active star in X-rays", Astronomy and Astrophysics 497 (2): 511–520, doi:10.1051/0004-6361/200811348, Bibcode: 2009A&A...497..511R.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Belle, Gerard T. van; Ciardi, David R.; Thompson, Robert R.; Akeson, Rachel L.; Lada, Elizabeth A. (2001). "Altair's Oblateness and Rotation Velocity from Long-Baseline Interferometry" (in en). The Astrophysical Journal 559 (2): 1155–1164. doi:10.1086/322340. ISSN 0004-637X. Bibcode: 2001ApJ...559.1155V. http://stacks.iop.org/0004-637X/559/i=2/a=1155.

- ↑ "the definition of altair" (in en). https://www.dictionary.com/browse/altair.

- ↑ "IAU Working Group on Star Names (WGSN)". https://www.iau.org/science/scientific_bodies/working_groups/280/.

- ↑ "Bulletin of the IAU Working Group on Star Names, No. 1". http://www.pas.rochester.edu/~emamajek/WGSN/WGSN_bulletin1.pdf.

- ↑ "IAU Catalog of Star Names". http://www.pas.rochester.edu/~emamajek/WGSN/IAU-CSN.txt.

- ↑ Hanbury Brown, R.; Davis, J.; Allen, L. R.; Rome, J. M. (1967). "The stellar interferometer at Narrabri Observatory-II. The angular diameters of 15 stars". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 137 (4): 393. doi:10.1093/mnras/137.4.393. Bibcode: 1967MNRAS.137..393H.

- ↑ Ohishi, Naoko; Nordgren, Tyler E.; Hutter, Donald J. (2004). "Asymmetric Surface Brightness Distribution of Altair Observed with the Navy Prototype Optical Interferometer". The Astrophysical Journal 612 (1): 463–471. doi:10.1086/422422. Bibcode: 2004ApJ...612..463O.

- ↑ Domiciano de Souza, A.; Kervella, P.; Jankov, S.; Vakili, F.; Ohishi, N.; Nordgren, T. E.; Abe, L. (2005). "Gravitational-darkening of Altair from interferometry". Astronomy & Astrophysics 442 (2): 567–578. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20042476. Bibcode: 2005A&A...442..567D.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 "Gazing up at the Man in the Star?" (Press release). National Science Foundation. May 31, 2007. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ Knobel, E. B. (June 1895). "Al Achsasi Al Mouakket, on a catalogue of stars in the Calendarium of Mohammad Al Achsasi Al Mouakket". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 55 (8): 429–438. doi:10.1093/mnras/55.8.429. Bibcode: 1895MNRAS..55..429K.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Allen, Richard Hinckley (1899). Star-names and their meanings. unknown library. New York, Leipzig [etc.] G.E. Stechert. pp. 59–60. http://archive.org/details/bub_gb_5xQuAAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Gingerich, O. (1987). "Zoomorphic Astrolabes and the Introduction of Arabic Star Names into Europe". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500 (1): 89–104. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37197.x. Bibcode: 1987NYASA.500...89G.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Aboriginal mythology: an A-Z spanning the history of aboriginal mythology from the earliest legends to the present day, Mudrooroo, London: HarperCollins, 1994, ISBN:1-85538-306-3.

- ↑ (in Chinese) 香港太空館 - 研究資源 - 亮星中英對照表 , Hong Kong Space Museum. Accessed on line November 26, 2008.

- ↑ Mayers, William Frederick (1874). The Chinese reader's manual: A handbook of biographical, historical .... Harvard University. American Presbyterian Mission Press. pp. 97–98, 161. http://archive.org/details/chinesereadersm01mayegoog.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 p. 72, China, Japan, Korea Culture and Customs: Culture and Customs, Ju Brown and John Brown, 2006, ISBN:978-1-4196-4893-9.

- ↑ pp. 105–107, Magic Lotus Lantern and Other Tales from the Han Chinese, Haiwang Yuan and Michael Ann Williams, Libraries Unlimited, 2006, ISBN:978-1-59158-294-6.

- ↑ Ross, Malcolm; Pawley, Andrew; Osmond, Meredith (2007-03-01) (in en). The Lexicon of Proto-Oceanic: The Culture and Environment of Ancestral Oceanic Society. The physical environment. Volume 2. ANU E Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-921313-19-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=bJFfm59fVr4C.

- ↑ Kelley, David H.; Milone, Eugene F.; Aveni, A.F. (2011). Exploring Ancient Skies: A Survey of Ancient and Cultural Astronomy. New York, New York: Springer. p. 344. ISBN 978-1-4419-7623-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=ILBuYcGASxcC&pg=PA307.

- ↑ "'Anybody there?' Astronomers waiting for a reply from Altair". August 20, 2023. https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14985246.

- ↑ "NASA names next-gen lunar lander Altair". December 13, 2007. http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-121307a.html.

- ↑ "Results of the competition for the best personal names for the Be-103 and the Be-200 amphibious aircraft" (Press release). Beriev Aircraft Company. February 12, 2003. Archived from the original on 2021-11-05. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ Brown, A. G. A. (August 2018). "Gaia Data Release 2: Summary of the contents and survey properties". Astronomy & Astrophysics 616: A1. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/201833051. Bibcode: 2018A&A...616A...1G.

- ↑ BD+08 4236B -- Star in double system, database entry, SIMBAD. Accessed online November 25, 2008.

- ↑ BD+08 4238 -- Star in double system, database entry, SIMBAD. Accessed online November 25, 2008.

External links

- Star with Midriff Bulge Eyed by Astronomers, JPL press release, July 25, 2001.

- Spectrum of Altair

- Imaging the Surface of Altair, University of Michigan news release detailing the CHARA array direct imaging of the stellar surface in 2007.

- PIA04204: Altair, NASA. Image of Altair from the Palomar Testbed Interferometer.

- Altair, SolStation.

- Secrets of Sun-like star probed, BBC News, June 1, 2007.

- Astronomers Capture First Images of the Surface Features of Altair , Astromart.com

- Image of Altair from Aladin.

Coordinates: ![]() 19h 50m 46.9990s, +08° 52′ 05.959″

19h 50m 46.9990s, +08° 52′ 05.959″

|

Categories: [Aquila (constellation)] [A-type main-sequence stars] [Multiple stars] [Flamsteed objects] [Bayer objects] [Henry Draper Catalogue objects] [Hipparcos objects] [Bright Star Catalogue objects] [Delta Scuti variables] [Stars with proper names] [Durchmusterung objects] [G-Cloud] [Astronomical objects known since antiquity] [Gliese and GJ objects]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 08/26/2024 20:06:08 | 3 views

☰ Source: https://handwiki.org/wiki/Astronomy:Altair | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

KSF

KSF