Murray River

From Nwe

From Nwe | Murray River | |

|---|---|

| Murray River at Murray Bridge | |

| Origin | Australian Alps |

| Mouth | Goolwa, South Australia |

| Basin countries | Australia |

| Length | 2,575 km (1,600 mi) |

| Avg. discharge | 767 m³/s |

| Basin area | 1,061,469 km² |

The Murray River, or River Murray and sometimes informally referred to as the "Mighty Murray," is Australia's largest river. It rises in the Australian Alps, draining the western side of Australia's highest mountains and meanders across Australia's inland plains, forming the border between New South Wales and Victoria.

The Murray is one of the major river systems in one of the driest continents on Earth, and as such has significant cultural relevance to Indigenous Australians. Forming 1,600 miles (2,575 km) of the 2,300 mile (3,700 km) long combined Murray-Darling river system which drains most of inland Victoria, New South Wales, and southern Queensland, its catchment area is one-seventh of Australia's land mass. Understandably, it has life-sustaining significance to modern populations throughout much of southern Australia. The river and its tributaries support a variety of unique river life adapted to its vagaries and supports fringing corridors and forests of the famous river red gum (eucalyptus).

The Murray River is crucial to life in Australia. However, the river's health has declined significantly and much of its aquatic life, including native fish, are now either declining, rare or endangered. Introduced fish species, disruption of its natural flow through damming, and run-off from agriculture has had negative effects on its ecosystem throughout its length. The large city of Adelaide, dependent on the Murray for nearly half its water supply, has at times received water that, by World Health Organization criteria, is unfit for drinking. The salinity problem of the river has been recognized as being of national significance to Australia.

Efforts to alleviate the river's problems proceed but disagreement between interested groups stalls progress. Success will come on the basis of positive interaction and shared knowledge and resources among those with common goals.

Mythology

The Murray River is one of the major river systems in one of the driest continents of Earth, and as such has significant cultural relevance to Indigenous Australians.

According to the peoples of Lake Alexandrina, the Murray was created by the tracks of the Great Ancestor, Ngurunderi, as he pursued Pondi, the Murray Cod. The chase originated in the interior of New South Wales. Ngurunderi pursued the fish (who, like many totem animals in Aboriginal myths, is often portrayed as a man) on rafts constructed from Eucalyptus and continually launched spears at his target. But Pondi was a wily prey and carved a weaving path, carving out the river's various tributaries. Ngurundi was forced to beach his rafts often and create new ones as he changed from reach to reach of the river.

At Kobathatang, Ngurunderi was finally lucky enough to strike Pondi in the tail with a spear. However, the shock to the fish was so great that it launched him forward in a straight line to a place called Peindjalang, near Tailem Bend. Eager to rectify his failure to catch his prey, the hunter and his two wives (sometimes told as the escaped sibling wives of Waku and Kanu) hurried on, and took positions high on the cliff on which Tailem Bend now stands. They sprung an ambush on Pondi only to fail again. Ngurunderi again set off in pursuit, but lost his prey as Pondi dived into Lake Alexandrina. Ngurunderi and his women settled on the shore, only to suffer bad luck with fishing, being plagued by a water fiend known as Muldjewangk. They later moved to a more suitable spot at the site of present-day Ashville. The twin summits of Mount Misery are the remnants of his rafts; known as Lalangengall or the two watercraft.

This story of a hunter pursuing a Murray cod and in the process creating the Murray River persists in numerous forms in various language groups that inhabit the enormous area spanned by the Murray system. The Wotojobaluk people of Victoria tell of Totyerguil from the area now known as Swan Hill who ran out of spears while chasing Otchtout the cod.

Geography

The Murray River forms part of the 2,300 mile (3,750 kilometer) long combined Murray-Darling river system which drains most of inland Victoria, New South Wales, and southern Queensland. Overall the catchment area is one-seventh of Australia's land mass. The Murray carries only a small fraction of the water of comparably-sized rivers in other parts of the world, and with a great annual variability of its flow. In its natural state it has been known to dry up completely in extreme drought, although that is extremely rare, with only two or three instances of this occurring since official record-keeping began.

The Murray makes up much of the border of the Australian states of Victoria and New South Wales. The border is generally agreed upon to be the southern high water mark of the river, meaning none of the river itself is actually in Victoria. This boundary definition can be ambiguous, as the river has changed its course slightly since the boundary was defined in 1851.

West of the 141°E line of longitude, the river continues as the Victoria - South Australia border for just over two miles (3.6 km), this being the only stretch where an Australian state border runs down the middle of the river. This was due to a miscalculation in the 1840s when the border was originally surveyed. Past this point, the Murray River is entirely within the state of South Australia.

River crossings

Due to the wide crossing and high clearance required to allow river boats to pass even during floods, and relatively low traffic requirements in South Australia, there are very few bridges across the Murray River. Most crossings are cable ferries operated by the South Australian Department of Transport. These ferries are known locally as punts, presumably as the original ferries were punts before the cable ferries replaced them to provide for heavier loads and greater safety. Both the ferries and the bridges are toll-free. Many of the ports for transport of goods along the Murray have also developed as river crossings, either by bridge or ferry.

River life

The Murray River and associated tributaries support a variety of unique river life adapted to its vagaries. This includes a variety of native fish such as the famous Murray cod, trout cod, golden perch, Macquarie perch, silver perch, eel-tailed catfish, Australian smelt, and western carp gudgeon, to name a few, and other aquatic species such as the Murray short-necked turtle, Murray River crayfish, broad-clawed yabbies, and the large clawed Macrobrachium shrimp, as well as aquatic species more widely distributed through southeastern Australia such as common long-necked turtles, common yabbies, the small claw-less Parataya shrimp, water rats, and Platypus. The Murray River also supports fringing corridors and forests of the famous river red gum.

The health of the Murray River has declined significantly since European settlement, particularly due to river regulation, and much of its aquatic life including native fish are now either declining, rare or endangered. Extreme droughts that occurred from 2000–2007 have put significant stress on river red gum forests, with mounting concern over their long term survival. The Murray has also flooded on occasion, the most significant of which was the "1956 Murray River flood," which inundated many towns on the lower Murray and lasted for up to six months.

Introduced fish species such as Carp, Gambusia, weather loach, redfin perch, and brown and rainbow trout have also had serious negative effects on native fish, while Carp have contributed to environmental degradation of the Murray River and tributaries by destroying aquatic plants and permanently raising turbidity. In some segments of the Murray, carp have been the only species found.

Mouth of the river

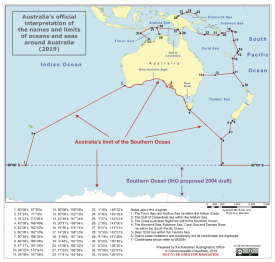

The Murray Mouth (35°33′S 138°53′E) is the point at which the Murray River empties into the Southern Ocean, according to the Australian definition of the ocean which includes the entire body of water between Antarctica and the south coasts of Australia and New Zealand, and up to 60°S elsewhere.

The mouth is between two sandhill peninsulas. Sir Richard Peninsula on the northwest separates the Goolwa channel (the main river channel) from the ocean. The much longer Younghusband Peninsula separates the Coorong from the ocean on the southeast of the mouth. The Murray Mouth is separated from Lake Alexandrina by a row of low islands. The largest one, directly facing the mouth, is Hindmarsh Island. A series of barrages join the islands, separating the salt water from the fresh water of the lakes and river. The barrages can be opened during high river flow.

When early European explorers looked for the mouth of the river they had high hopes of finding a natural harbor suitable for shipping. Had they found such a harbor, the Murray would have been utilized as a means of connecting many parts of inland Australia with the coast and beyond. Instead, what Captain Charles Sturt found was a treacherous river mouth that punched a channel through sand dunes into the sea.

At the time we had arrived at the end of the channel the tide had turned and was again setting in. The entrance appeared to me to be somewhat less than a quarter mile in breadth. Under the sandhill on the off side the water is deep and the current strong… The mouth of the channel is defended by a double line of breakers amidst which it would be dangerous to venture except in calm and summer weather… Thus our fears of the impracticability and in-utility of the channel of communication between the lake and ocean confirmed (Charles Sturt, February 12, 1830, quoted in South Coast Story, J.C. Tolley 1968).

Historical records show that the channel to the sea moves along the sand dunes over time. At times of greater river flow and rough seas, the two bodies of water would erode the sand dunes to create a new channel leaving the old one to silt and disappear.

At high tides, seawater flows in through the channel and into the Coorong National Park's lagoon system. At the mouth, the Murray flows eastward until it turns south for the last few hundred meters. To the east of the mouth, river water and high tide seawater can continue eastward for over a 62 miles (100km) into magnificent saltwater lagoons protected from the fierce ocean by tall sand dunes.

Since October 2002, two dredging machines have operated at the Murray Mouth, moving sand from the channel to maintain a minimal flow from the sea and into the Coorong's lagoon system. Without the 24-hour dredging, the Mouth would silt up and close, cutting the supply of fresh seawater into the Coorong, which would then warm up, stagnate and die. In mid-2006, the dredging was scaled back as a result of the improved conditions at the mouth. One dredging machine continues to operate, and permission was granted to one commercial operator to navigate the channel between Goolwa and the Coorong, passing the mouth.

History

Lake Bungunia

Between 2.5 and 0.5 million years ago the Murray River terminated in a vast freshwater lake called Lake Bungunia. Lake Bungunia was formed by earth movement that blocked the Murray River near Swan Reach during this period of time. At its maximum extent Lake Bungunia covered 12,740 square miles (33,000 sq km), extending to near the Menindee Lakes in the north and to near Boundary Bend on the Murray in the south. The draining of Lake Bungunia approximately 0.5 million years ago must have been a dramatic event. Deep clays deposited by the lake are evident in cliffs around Chowilla in South Australia. Considerably higher rainfall than is experienced in present day would have been required to keep such a lake full; the draining of Lake Bungunia appears to mark the end of a wet phase in the history of the Murray-Darling Basin and the onset of widespread arid conditions similar to today. A species of Neoceratodus lungfish existed in Lake Bungunia (McKay & Eastburn, 1990); today Neoceratodus lungfish are only found in several Queensland rivers.

Cadell Fault and formation of the Barmah Red Gum Forests

The famous Barmah Red Gum Forests owe their existence to the Cadell Fault. About 25,000 years ago, displacement occurred along the Cadell fault, raising the eastern edge of the fault (which runs north-south) 8-12 meters above the floodplain, creating a complex series of events. A section of the original Murray River channel immediately behind the fault was abandoned, and exists today as an empty channel known as Green Gully. The Goulburn River was dammed by the southern end of the fault to create a natural lake. The Murray River flowed to the north around the Cadell Fault, creating the channel of the Edward River which exists today and through which much of the Murray River's waters still flow. Then the natural dam on the Goulburn River failed, the lake drained, and the Murray River avulsed to the south and began to flow through the smaller Goulburn River channel, creating "The Barmah Choke" and "The Narrows" (where the river channel is unusually narrow), before entering into the proper Murray River channel again.

This complex series of events, however, divert attention from the primary result of the Cadell Fault. The primary result being that the west-flowing water of the Murray River strikes the north-south running fault and diverts both north and south around the fault in the two main channels (Edward and ancestral Goulburn) as well as a fan of small streams, and regularly floods a large amount of low-lying country in the area. These conditions are perfect for Eucalyptus, which rapidly formed forests in the area. Thus the displacement of the Cadell Fault lead directly to the formation of the famous Barmah River Red Gum Forests.

The Barmah Choke and The Narrows mean the amount of water that can travel down this part of the Murray River is restricted. In times of flood and high irrigation-flows the majority of the water, in addition to flooding the Red Gum forests, actually travels through the Edward River channel. The Murray River has not had enough flow power to naturally enlarge The Barmah Choke and The Narrows to increase the amount of water they can carry.

The Cadell Fault is quite noticeable as a continuous, low, earthen embankment as one drives into Barmah from the west, although to the untrained eye it may appear human-made.

Exploration

The first Europeans to explore the river were Hamilton Hume and William Hovell, who crossed the river where Albury now stands in 1824: Hume named it the Hume River after his father. In 1830, Captain Charles Sturt reached the river after traveling down its tributary the Murrumbidgee River and named it the Murray River in honor of the then British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies Sir George Murray, not realizing it was the same river that Hume and Hovell had encountered further upstream. Sturt continued down the remaining length of the Murray to finally reach Lake Alexandrina and the river's mouth.

The area of the Murray Mouth was explored more thoroughly by Captain Collet Barker in 1831. In 1852, Francis Cadell built a canoe and set off to become the first European to travel the whole length of the river.

In 1858, the Government Zoologist, William Blandowski, along with Gerard Krefft, explored the lower reaches of the Murray and Darling rivers, compiling a list of birds and mammals. During the expedition they accumulated 17,400 specimens and described several new species.

River transport

During the nineteenth century, the river supported a substantial commercial trade using shallow-draft steamboats, the first trips being made by two boats from South Australia on the spring flood of 1853. One vessel, Lady Augusta, reached Swan Hill while another, Mary Ann made it as far as Moama in New South Wales. In 1855, a steamer carrying gold-mining supplies reached Albury but Echuca was the usual turn-around point, though small boats continued to link with up-river ports such as Tocumwal, New South Wales, Wahgunyah, Victoria, and Albury.

The arrival of steamboat transport was welcomed by pastoralists who had been suffering from a shortage of transport due to the demands of the gold fields. By 1860, a dozen steamers were operating in the high-water season along the Murray and its tributaries. Once the railway reached Echuca in 1864, the bulk of the woolclip from the Riverina was transported via river to Echuca and then south to Melbourne. The Murray was plagued by "snags," fallen trees submerged in the water, and considerable efforts were made to clear the river of these threats to shipping by using barges equipped with steam-driven winches. In recent times, efforts have been made to restore many of these "snags" by placing dead gum trees back into the river. The primary purpose of this is to provide habitat for fish species whose breeding grounds and shelter were eradicated by the removal of snags.

The volume and value of river trade made Echuca Victoria's second port and in the decade from 1874 it underwent considerable expansion. By this time up to thirty steamers and a similar number of barges were working the river in season. River transport began to decline once the railways touched the Murray at numerous points. The unreliable water levels made it impossible for boats to compete with the rail and later road transport. However, the river still carries pleasure boats along its entire length.

Today, most traffic on the river is recreational. Small private boats are used for water skiing and fishing. Houseboats are common, both commercial for hire and privately owned. There are a number of both historic paddle steamers and newer boats offering cruises ranging from a half-hour to five days.

Water storage and irrigation

Small-scale pumping plants began drawing water from the Murray in the 1850s and the first large-volume plant was constructed at Mildura in 1887. The introduction of pumping stations along the river promoted an expansion of farming and led ultimately to the development of irrigation areas (including the Murrumbidgee Irrigation Area).

In 1915, the three Murray states—New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia—signed the River Murray Agreement which proposed the construction of storage reservoirs in the river's headwaters as well as at Lake Victoria near the South Australian border. Along the intervening stretch of the river a series of locks and weirs were built. These were originally proposed to support navigation even in times of low water, but river-borne transport was already declining due to improved road and rail systems.

In 2006, the state government of South Australia revealed their plan to investigate the construction of the controversial Wellington Weir.

Locks

Lock 1 was completed near the city of Blanchetown in 1922. Torrumbarry Weir downstream of Echuca began operating in December 1923. Of the numerous locks that were proposed, only thirteen were completed; Locks 1 to 11 on the stretch downstream of Mildura, Lock 15 at Euston and Lock 26 at Torrumbarry. Construction of the remaining weirs purely for navigation purposes was abandoned in 1934. The last lock to be completed was Lock 15, in 1937.

Lock 11, just downstream of Mildura, creates a 62 mile (100 km) long lock pool which aided irrigation pumping from Mildura and Red Cliffs. Each lock has a navigable passage next to it through the weir, which is opened during periods of high river flow, when there is too much water for the lock. The weirs can be completely removed, and the locks completely covered by water during flood conditions. Lock 11 is unique in that the lock was built inside a bend of the river, with the weir in the bend itself. A Channel was dug to the lock, creating an island between it and the weir. The weir is also of a different design, being dragged out of the river during high flow, rather than lifted out.

Four large reservoirs were built along the Murray; in addition to Lake Victoria (completed late 1920s) is Lake Hume near Albury-Wodonga (completed 1936), Lake Mulwala at Yarrawonga (completed 1939) and Lake Dartmouth, which is actually on the Mitta Mitta River upstream of Lake Hume (completed 1979). The Murray also receives water from the complex dam and pipeline system of the Snowy Mountains Scheme.

Environmental problems

Dams on the Murray inverted the patterns of the river's natural flow from the original winter-spring flood and summer-autumn dry to the present low-level through winter and higher during summer. These changes ensured the availability of water for irrigation and made the Murray Valley Australia's most productive agricultural region, but have seriously disrupted the life cycles of many ecosystems both inside and outside the river, and the irrigation has led to dryland salinity that now threatens the agricultural industries. The large city of Adelaide, dependent on the Murray for nearly half its water supply, has at times received water that, by World Health Organization criteria, is unfit for drinking. The salinity problem of the river has been recognized as being of national significance to Australia.

The disruption of the river's natural flow, run-off from agriculture, and the introduction of pest species such as the European Carp has led to serious environmental damage along the river's length and to concerns that the river will be unusably salty in the medium to long term. Efforts to alleviate the problems proceed but disagreement between interested groups stalls progress.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Isaacs, Jennifer. 1980. Australian Dreaming: 40,000 Years of Aboriginal History. Sydney: Lansdowne Press. ISBN 9780701813307.

- Mackay, Norman, and David Eastburn. 1990. The Murray. Canberra, Australia: Murray Darling Basin Commission. ISBN 1875209050.

- Tolley, John C. 1968. South Coast Story. Mount Compass, SA: Rowett Print. ISBN 0958796432.

External links

All links retrieved November 10, 2022.

- Murray River EEC Department of Primary Industries.

- About the Murray River Discover Murray River

- The Murray Visit Melbourne

- Welcome to the Murray Visit the Murray

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 06:43:24 | 130 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Murray_River | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF