Anointing

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) Anointing.

Two words are employed in the Old Testament for Anointing,

and

and

. The former designates the private use of unguents in making one's toilet, the latter their use as a religious rite.

. The former designates the private use of unguents in making one's toilet, the latter their use as a religious rite.

As a means of soothing the skin in the fierce heat of the Palestinian climate, oil seems to have been applied to the exposed parts of the body, especially to the face (Ps. civ. 15); that this was a part of the daily toilet may be inferred from Matt. vi. 17. The practise is older than David, and runs throughout the Old Testament (see Deut. xxviii. 40; Ruth, iii. 3; II Sam. xii. 20, xiv. 2; II Chron. xxviii. 15; Ezek. xvi. 9; Micah, vi. 15; Dan. x. 3). Anointing accompanied a bath (Ruth, iii. 3; II Sam. xii. 20; Ezek. xvi. 9; Susanna, 17); it was a part of the toilet for a feast (Eccl. ix. 8, Ps. xxiii. 5) [in which a different term is poetically used] (Amos, vi. 6). Hence, it was omitted in mourning as a sign of grief (II Sam. xiv. 2, Dan. x. 3), and resumed to indicate that mourning was over (II Sam. xii. 20; Judith, x. 3).

The primary meaning of mashaḥ , which occurs also in Arabic, seems to have been to daub or smear. It is used (Jer. xxii. 14) of painting a ceiling and (Isa.xxi. 5) of anointing a shield. It is applied to sacred furniture, like the altar (Ex. xxix. 36, Dan. ix. 24), and to the sacred pillar (Gen. xxxi. 13): "where thou anointedst the pillar."

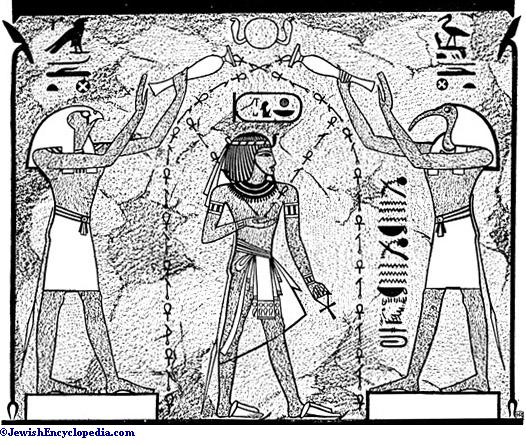

Anointing of King.The most important use of mashaḥ is in connection with certain sacred persons. The principal and oldest of these is the king, who was anointed from the earliest times (Judges, ix. 8, 15; I Sam. ix. 16, x. 1; II Sam. xix. 10; I Kings, i. 39, 45; II Kings, ix. 3, 6, xi. 12). So exclusively was Anointing reserved for the king in this period that "the Lord's anointed" became a synonym for king (I Sam. xii. 3, 5, xxvi. 11; II Sam. i. 14; Ps. xx. 7). This custom was older than the Hebrews. El-Amarna Tablet No. 37 tells of the anointing of a king.

In that section of the Pentateuch known as the Priestly Code the high priest is anointed (Ex. xxix. 7; Lev. vi. 13, viii. 12), and, in passages which critics regard as additions to the Priestly Code, other priests as well (Ex. xxx. 30, xl. 13-15). It appears from the use of "anointed priest," in the sense of high priest (Lev. iv. 5-7, 16; Num. xxxv. 25, etc.), that the high priest was at first the only one anointed, and that the practise of anointing all the priests was a later development (compare Num. iii. 3; Dillman on Lev. viii. 12-14; Nowack, "Lehrbuch der Hebräischen Archäologie," ii. 124). In the earliest times the priests were not anointed, but "their hands were filled," which probably means that they were hired (compare Judges, xvii. 5, 12; I Kings, xiii. 33; Wellhausen, "Prolegomena," 5th ed., pp. 155

et seq.

; Benzinger, "Lehrbuch der Hebräischen Archäologie," p. 407). Weinel (Stade's "Zeitschrift," xviii. 60

et seq.

) contests this view. The earliest mention of an anointed priest is in Zech. iv. 14; and as Ezek. xliii. 26 still uses "fill the hand" for "consecrated" (that Ezekiel uses it here figuratively for the altar does not materially affect the argument), we may infer that priests were not anointed before the middle of the sixth century

W. R. Smith found the origin of this sacred Anointing in the custom of smearing the sacred fat on the maẓẓebah , or altar ("Religion of the Semites," 2d ed., pp. 233, 383 et seq. ); so also Wellhausen ("Reste des Arabischen Heidenthums," 2d ed., pp. 125 et seq. ). Weinel maintains (Stade's "Zeitschrift," xviii. 50 et seq. ) that the use of oil is an agricultural custom borrowed from the Canaanites; that the offering of oil poured on an altar is parallel to the offering of first-fruits; thus the anointing of a king with sacred oil is an outgrowth from its regular use by all persons for toilet purposes.

From this latter view it seems difficult to account for the great sanctity of "the Lord's anointed." The different terms used would lead us to accept Robertson Smith's views of the origin of mashaḥ (namely, that it is nomadic and sacrificial) and to believe that the suk , or use of oil for toilet purposes, was of agricultural and secular origin; hence the distinct and consistent use of the two terms.

The first Biblical instance of Anointing as a sign of consecration—the pouring of oil by Jacob upon the stone of Beth-el —offered a problem to later speculative rabbis as to the source whence Jacob obtained the oil in that lonely spot. The reply was made by them that it must have "streamed down from heaven in quantity just sufficient for the purpose" (Gen. R. lxix., Pirḳe R. El. xxxv.). The oil of holy ointment prepared by Moses in the wilderness (Ex. xxx. 23 et seq. ) had many miraculous qualities: it was never absorbed by the many spices mixed therewith; its twelve logs (1.68 gallons) were sufficient for the anointment of all the kings and high priests of Israelitish history, and will be in use in the Messianic time to come. During the reign of Josiah this oil was hidden away simultaneously with the holy ark, to reappear in the Messianic time (Hor. 11 b et seq. ; Sifra, Milluim, 1).

As to the mode of anointment, an old rabbinical tradition relates (Hor. 12

a

, Ker. 5

b

) that "the kings were anointed in the form of a crown; that is, all around the head; and the high priests in the form of a Greek Chi (χ). In other words, in anointing the priests the oil was poured first upon the head and then upon the eyebrows (see Rashi, and "'Aruk,"

s.v.

; and, as against Kohut's dissertation, compare Plato, "Timæus," chap. xxxvi., referred to by Justin Martyr, "First Apology," lx.: "He impressed the soul as an unction in the form of the letter χ (chiasma) upon the universe." It is not unlikely that, owing to their opposition to the Christian cross, the Jewish interpreters adopted the

kaph

form instead of the χ—the original

tav

of Ezek. ix. 4.

; and, as against Kohut's dissertation, compare Plato, "Timæus," chap. xxxvi., referred to by Justin Martyr, "First Apology," lx.: "He impressed the soul as an unction in the form of the letter χ (chiasma) upon the universe." It is not unlikely that, owing to their opposition to the Christian cross, the Jewish interpreters adopted the

kaph

form instead of the χ—the original

tav

of Ezek. ix. 4.

The rule is stated that every priest, whether the son of a high priest or not, had to be anointed. The son of a king was, however, exempt, except for special reasons, as in the case of Joash, because of Athaliah (II Kings, xi. 12); Solomon, because of Adonijah (I Kings, i. 39); and Jehu, because of Joram's claims (II Kings, ix. 1 et seq. ); or of Jehoahaz, because Jehoiakim was two years his senior (II Kings, xxiii. 30). This rule was, however, modified, as indicated by the statement that David and Solomon were anointed from the horn (I Sam. xvi. 13; I Kings, i. 39) and Saul and Jehu from the cruse— pak (I Sam. x. 1; II Kings, ix. 3: the A. V. has "vial" and "box" in these respective passages). Another rule is mentioned, according to which the kings of the house of Israel were not anointed with the sacred oil at all. In their cases pure balsam was used instead; nor could the last reigning kings of Judah have been anointed with the sacred oil of consecration, since Josiah is said to have hidden it away (see Hor. 11 b ; Yer. Soṭah, viii. 22 c ; Yer. Hor. iii. 4 c ). Rabbinical tradition distinguishes also between the regular high priest and the priest anointed for the special purpose of leading in war— mashuaḥ milḥamah (Soṭah, viii. 1; Yoma, 72 b , 73 a ). According to tradition (see Josippon, xx.; Chronicle of Jerahmeel, xci. 3; compare I Macc. iii. 55), Judas Maccabeus was anointed as priest for the war before he proclaimed the words prescribed in Deut. xx. 1-9.

Anointing stands for greatness (Sifre, Num. 117; Yer. Bik. ii. 64 d ): consequently, "Touch not mine anointed" signifies "my great ones." All the vessels of the tabernacle, also, were consecrated with the sacred oil for all time to come (Num. R. xii.).

For Health and Comfort.As a rule, Anointing with oils and perfumes followed the bath (see Shab. 41 a ; Soṭah, 11 b ), the head being anointed first (Shab. 61 a ). On the Sabbath, Anointing whether for pleasure or for health, is allowed (Yer. Ma'as. Sh. ii. 53 b ; Yer. Shab. ix. 12 a , based on Mishnah Shab. ix. 4; compare Tosef., Shab. iii. [iv.] 6).

It is forbidden, however, in both instances on the Day of Atonement (compare Yoma, viii. 1,76 b ); whereas on the Ninth of Ab and other fast-days it is permitted for health only (compare Ta'anit, 127 b ), and is declared as enjoyable as drinking (Shab. ix. 4).

Anointing as a remedy in case of skin diseases is mentioned in Yer. Ma'as. Sh. ii. 53 a ; Bab. Yoma, 77 b ; and Yer. Shab. xiv. 14 c ; but at the same time incantations were used, the person anointing the head with oil also pronouncing an incantation over the sore spots ( loḥesh 'al ha-makkah ) exactly as stated in the Epistle of James, v. 14, and Mark, vi. 13 (compare Isa. i. 6; Ps. cix. 18; Luke, x. 34).

Men should not go out on the street perfumed (Ber. 43 b ); but women perfume themselves when going out (see Josephus, "B. J." iv. 9, § 10). A wife could demand one-tenth of her dowry-income for unguents and perfumes; the daughter of the rich Nicodemus ben Gorion was accustomed to spend annually four hundred gold denarii for the same (Ket. 66 b ). These facts serve to cast light on the story of Luke, vii. 38-46, and John, xii. 3.

When Adam, in his nine hundred and thirtieth year, was seized with great pain during his sickness, he told Eve to "take Seth with her to the neighborhood of paradise and pray to God that He should send an angel with oil from the tree of mercy, in order that they might anoint Adam therewith and release him from his pain" (Apocalypse Mosis, 13; Vita Adæ et Evæ, 36-4). What follows here seems to be the work of a Christian writer or interpolator, and corresponds with "Evangelium Nicodemi," ch. 19, "Descensus," ch. 3. Compare the baptismal rite of the Elkesaites in Hippolytus," "Refutation of Heresies"; the baptismal formula of the Ophites in Origen, "Contra Celsum," vi. 27, "I have been anointed with the white ointment from the tree of life"; and the Ebionitic view of Christ and Adam as the first prophet anointed with oil from the tree of life, while the ointment of Aaron was made after the mode of the heavenly ointment in the Clementine "Recognitiones," xlv.-xlvii. "The pious anoint themselves with the blessed ointment of incorruption" ("Prayer of Aseneth," chaps. viii. and xv.). Compare also the mystery of the spiritual ointment, in the Gnostic books (Schmidt, "Gnostische Schriften in Koptischer Sprache," pp. 195, 339 et seq. , 377, 492, 509).

- Hastings, Dict. s.v.;

- Hamburger, R. B. T. s.v. Salbe and Salböl.

Categories: [Jewish encyclopedia 1906]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 09/04/2022 17:46:58 | 73 views

☰ Source: https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/1559-anointing.html | License: Public domain

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF