Fractal

From Nwe

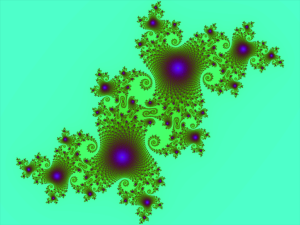

From Nwe A fractal is an irregular geometric shape that can be divided into parts in such a manner that the shape of each part resembles the shape of the whole. This property is called self-similarity. However, not all self-similar objects are fractals. For example, a straight Euclidean line (or real line) is formally self-similar, but it is regular enough to be described in Euclidean terms.

Images of fractals can be created using fractal generating software. Such software allows scientists to construct computer models of natural objects with irregular shapes that approximate fractals to some degree. These objects include clouds, coastlines, mountain ranges, lightning bolts, and snowflakes.

Etymology

The term fractal was coined by Benoît Mandelbrot in 1975 and was derived from the Latin word fractus, meaning "broken" or "fractured." In his book The Fractal Geometry of Nature, Mandelbrot describes a fractal as "a rough or fragmented geometric shape that can be split into parts, each of which is (at least approximately) a reduced-size copy of the whole."[1]

Features

A mathematical fractal is based on an equation that undergoes iteration, a form of feedback based on recursion.[2]

A fractal often has the following features:[3]

- It has a fine structure at arbitrarily small scales.

- It is too irregular to be easily described in traditional Euclidean geometric language.

- It is self-similar (at least approximately or stochastically).

- It has a Hausdorff dimension which is greater than its topological dimension (although this requirement is not met by space-filling curves such as the Hilbert curve).

- It has a simple and recursive definition.

History

The mathematics behind fractals began to take shape in the seventeenth century when mathematician and philosopher Leibniz considered recursive self-similarity (although he made the mistake of thinking that only the straight line was self-similar in this sense).

It took until 1872 before a function appeared whose graph would today be considered fractal, when Karl Weierstrass gave an example of a function with the non-intuitive property of being everywhere continuous but nowhere differentiable. In 1904, Helge von Koch, dissatisfied with Weierstrass's very abstract and analytic definition, gave a more geometric definition of a similar function, which is now called the Koch snowflake. In 1915, Waclaw Sierpinski constructed his triangle and, one year later, his carpet. Originally these geometric fractals were described as curves rather than the 2D shapes that they are known as in their modern constructions. In 1918, Bertrand Russell had recognized a "supreme beauty" within the mathematics of fractals that was then emerging.[2] The idea of self-similar curves was taken further by Paul Pierre Lévy, who, in his 1938 paper Plane or Space Curves and Surfaces Consisting of Parts Similar to the Whole described a new fractal curve, the Lévy C curve.

Georg Cantor also gave examples of subsets of the real line with unusual properties—these Cantor sets are also now recognized as fractals.

Iterated functions in the complex plane were investigated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries by Henri Poincaré, Felix Klein, Pierre Fatou and Gaston Julia. However, without the aid of modern computer graphics, they lacked the means to visualize the beauty of many of the objects that they had discovered.

In the 1960s, Benoît Mandelbrot started investigating self-similarity in papers such as How Long Is the Coast of Britain? Statistical Self-Similarity and Fractional Dimension, which built on earlier work by Lewis Fry Richardson. Finally, in 1975 Mandelbrot coined the word "fractal" to denote an object whose Hausdorff-Besicovitch dimension is greater than its topological dimension. He illustrated this mathematical definition with striking computer-constructed visualizations. These images captured the popular imagination; many of them were based on recursion, leading to the popular meaning of the term "fractal."

Examples

A class of examples is given by the Cantor sets, Sierpinski triangle and carpet, Menger sponge, dragon curve, space-filling curve, and Koch curve. Additional examples of fractals include the Lyapunov fractal and the limit sets of Kleinian groups. Fractals can be deterministic (all the above) or stochastic (that is, non-deterministic). For example, the trajectories of the Brownian motion in the plane have a Hausdorff dimension of two.

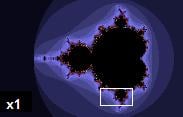

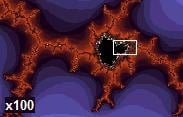

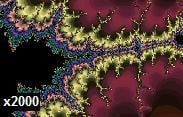

Chaotic dynamical systems are sometimes associated with fractals. Objects in the phase space of a dynamical system can be fractals (see attractor). Objects in the parameter space for a family of systems may be fractal as well. An interesting example is the Mandelbrot set. This set contains whole discs, so it has a Hausdorff dimension equal to its topological dimension of two—but what is truly surprising is that the boundary of the Mandelbrot set also has a Hausdorff dimension of two (while the topological dimension of one), a result proved by Mitsuhiro Shishikura in 1991. A closely related fractal is the Julia set.

Even simple smooth curves can exhibit the fractal property of self-similarity. For example the power-law curve (also known as a Pareto distribution) produces similar shapes at various magnifications.

Generating fractals

|

|

|

Even 2000 times magnification of the Mandelbrot set uncovers fine detail resembling the full set. Even 2000 times magnification of the Mandelbrot set uncovers fine detail resembling the full set. |

Four common techniques for generating fractals are:

-

- Escape-time fractals — (also known as "orbits" fractals) These are defined by a formula or recurrence relation at each point in a space (such as the complex plane). Examples of this type are the Mandelbrot set, Julia set, the Burning Ship fractal, the Nova fractal and the Lyapunov fractal. The 2d vector fields that are generated by one or two iterations of escape-time formulae also give rise to a fractal form when points (or pixel data) are passed through this field repeatedly.

- Iterated function systems — These have a fixed geometric replacement rule. Cantor set, Sierpinski carpet, Sierpinski gasket, Peano curve, Koch snowflake, Harter-Heighway dragon curve, T-Square, Menger sponge, are some examples of such fractals.

- Random fractals — Generated by stochastic rather than deterministic processes, for example, trajectories of the Brownian motion, Lévy flight, fractal landscapes and the Brownian tree. The latter yields so-called mass- or dendritic fractals, for example, diffusion-limited aggregation or reaction-limited aggregation clusters.

- Strange attractors — Generated by iteration of a map or the solution of a system of initial-value differential equations that exhibit chaos.

Classification

Fractals can also be classified according to their self-similarity. There are three types of self-similarity found in fractals:

-

- Exact self-similarity — This is the strongest type of self-similarity; the fractal appears identical at different scales. Fractals defined by iterated function systems often display exact self-similarity.

- Quasi-self-similarity — This is a loose form of self-similarity; the fractal appears approximately (but not exactly) identical at different scales. Quasi-self-similar fractals contain small copies of the entire fractal in distorted and degenerate forms. Fractals defined by recurrence relations are usually quasi-self-similar but not exactly self-similar.

- Statistical self-similarity — This is the weakest type of self-similarity; the fractal has numerical or statistical measures which are preserved across scales. Most reasonable definitions of "fractal" trivially imply some form of statistical self-similarity. (Fractal dimension itself is a numerical measure which is preserved across scales.) Random fractals are examples of fractals which are statistically self-similar, but neither exactly nor quasi-self-similar.

In nature

Approximate fractals are easily found in nature. These objects display self-similar structure over an extended, but finite, scale range. Examples include clouds, snow flakes, crystals, mountain ranges, lightning, river networks, cauliflower or broccoli, and systems of blood vessels and pulmonary vessels. Coastlines may be loosely considered fractal in nature.

Trees and ferns are fractal in nature and can be modeled on a computer by using a recursive algorithm. This recursive nature is obvious in these examples—a branch from a tree or a frond from a fern is a miniature replica of the whole: not identical, but similar in nature. The connection between fractals and leaves are currently being used to determine how much carbon is really contained in trees. This connection is hoped to help determine and solve the environmental issue of carbon emission and control. [4]

In 1999, certain self similar fractal shapes were shown to have a property of "frequency invariance"—the same electromagnetic properties no matter what the frequency—from Maxwell's equations (see fractal antenna).[5]

- widths="200px"

-

Fractal pentagram drawn with a vector iteration program

In creative works

Fractal patterns have been found in the paintings of American artist Jackson Pollock. While Pollock's paintings appear to be composed of chaotic dripping and splattering, computer analysis has found fractal patterns in his work.[6]

Decalcomania, a technique used by artists such as Max Ernst, can produce fractal-like patterns.[7] It involves pressing paint between two surfaces and pulling them apart.

Fractals are also prevalent in African art and architecture. Circular houses appear in circles of circles, rectangular houses in rectangles of rectangles, and so on. Such scaling patterns can also be found in African textiles, sculpture, and even cornrow hairstyles.[8]

- widths="200px"

Applications

As described above, random fractals can be used to describe many highly irregular real-world objects. Other applications of fractals include:[10]

- Classification of histopathology slides in medicine

- Fractal landscape or Coastline complexity

- Enzyme/enzymology (Michaelis-Menten kinetics)

- Generation of new music

- Generation of various art forms

- Signal and image compression

- Creation of digital photographic enlargements

- Seismology

- Fractal in soil mechanics

- Computer and video game design, especially computer graphics for organic environments and as part of procedural generation

- Fractography and fracture mechanics

- Fractal antennas—Small size antennas using fractal shapes

- Small angle scattering theory of fractally rough systems

- T-shirts and other fashion

- Generation of patterns for camouflage, such as MARPAT

- Digital sundial

- Technical analysis of price series (see Elliott wave principle)

See also

- Bifurcation theory

- Butterfly effect

- Chaos theory

- Complexity

- Constructal theory

- Diamond-square algorithm

- Fractal compression

- Fractal cosmology

- Fractal flame

- Fractal landscape

- Fractint

- Fracton

- Graftal

- Greeble

- Lacunarity

- Newton fractal

- Recursionism

- Sacred geometry

- Self-reference

- Strange loop

- Turbulence

Notes

- ↑ Mandelbrot, B.B. 1982. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. San Francisco, CA: W.H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0716711869.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 John Briggs, 1992, Fractals:The Patterns of Chaos. London, UK: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0500276935. 148.

- ↑ Kenneth Falconer, 2003, Fractal Geometry: Mathematical Foundations and Applications. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. ISBN 0470848626. xxv.

- ↑ "Hunting the Hidden Dimension." Nova. PBS. WPMB-Maryland.

- ↑ R. Hohlfeld, and N. Cohen. 1999. Self-similarity and the geometric requirements for frequency independence in antennae. Fractals. 7(1):79-84.

- ↑ Taylor, Richard, Adam P. Micolich, and David Jonas. Fractal Expressionism : Can Science Be Used To Further Our Understanding Of Art? phys.unsw.edu.au. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Michael Frame, and Benoît B. Mandelbrot. A Panorama of Fractals and Their Uses. Yale. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Ron Eglash, 1999, African Fractals: Modern Computing and Indigenous Design. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813526140. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Peng, Gongwen, Decheng Tian. 1990. The fractal nature of a fracture surface. Journal of Physics A. 23(14):3257–3261. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Applications. ThinkQuest. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barnsley, Michael F., and Hawley Rising. Fractals Everywhere. Morgan Kaufmann Pub., 1993. ISBN 0120790610.

- Falconer, Kenneth. Techniques in Fractal Geometry. New York, NY: John Willey and Sons, 1997 (original 1990). ISBN 0471922870.

- Gouyet, Jean-François. Physics and Fractal Structures. Paris, FR: Masson; New York, NY: Springer, 1996. ISBN 2225851301.

- Jones, Jesse. Fractals for the Macintosh. Corte Madera, CA: Waite Group Press, 1993. ISBN 1878739468.

- Jürgens, Hartmut, Heins-Otto Peitgen, and Dietmar Saupe. Chaos and Fractals: New Frontiers of Science. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 1992. ISBN 0387979034.

- Lauwerier, Hans, and Sophia Gill-Hoffstadt trans. Fractals: Endlessly Repeated Geometrical Figures. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1991. ISBN 069108551X. - "This book has been written for a wide audience..." Includes sample BASIC programs in an appendix.

- Lesmoir-Gordon, Nigel, Ian Stewart, Paul Sinclair, David Gilmour, and Arthur C Clarke. The Colours of Infinity: The Beauty, The Power and the Sense of Fractals. Bath, UK: Clear, 2004. ISBN 1904555055. (The book comes with a related DVD of the Arthur C. Clarke documentary introduction to the fractal concept and the Mandelbrot set.

- Mandelbrot, Benoît B. The Fractal Geometry of Nature. New York, NY: W.H. Freeman and Co., 1982. ISBN 0716711869.

- Peitgen, Heinz-Otto, and Dietmar Saupe, eds. The Science of Fractal Images. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag, 1988. ISBN 0387966080.

- Pickover, Clifford A. ed. Chaos and Fractals: A Computer Graphical Journey - A 10 Year Compilation of Advanced Research. Amsterdam, NL; New York, NY: Elsevier, 1998. ISBN 0444500022.

- Sprott, Julien Clinton. Chaos and Time-Series Analysis. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 0198508395.

- Wahl, Bernt, Peter Van Roy, Michael Larsen, and Eric Kampman. Exploring Fractals on the Macintosh. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley, 1995. ISBN 0201626306.

External links

All links retrieved April 20, 2017.

- Fractal Geometry – An introductory course on fractals at Yale University.

- A Fractals Unit for Elementary and Middle School Students

- The Chaos Hypertextbook.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:17:42 | 18 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Fractal | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF