Continental Congress

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia The Continental Congress refers to two separate organizations that played a major role in leading the Thirteen Colonies into the American Revolution. The First set the stage in 1774. The Second became the national government of the United Colonies, which in July 1776 became the United States of America. Both congresses met in Philadelphia and were composed of delegates selected by the 13 colonies/states. The Second Continental Congress in March 1781 took a new name, "The United States in Congress Assembled", when it came under the jurisdiction of the Articles of Confederation. The Congress was a weak national government—there was no president or executive branch, and no judges; most business was handled by committees.

Contents

Background[edit]

The idea of a central government for the 13 main British colonies in America dates to the Albany Congress of 1754. Led by Benjamin Franklin there were discussions about unity for more effective defense against the French and Indians. The Albany Congress drafted a plan that proposed a central government with the power to raise troops and levy taxes for colonial defense, to dispose of western lands and create new colonies, and to regulate Indian affairs. Colonial legislatures rejected the plan and Great Britain ignored it.

After the expulsion of France from North America in 1763, there was no longer an external danger to the colonies. They did not need British military or naval protection. The British, however, insisted on imposing a series of taxes such as those contained in the Stamp Act, partly to raise revenue and partly to demonstrate the superiority of Parliament. The Americans insisted that they possessed the traditional rights of Englishmen and only their elected officials had the power to raise taxes; they were not represented in Parliament, which therefore could not levy taxes. The dispute was unbridgeable, especially as Americans started adopting republican political ideas that warned the aristocratic British system was corrupt and dangerous. Popular leaders in the colonies, such as Samuel Adams in Massachusetts and Patrick Henry in Virginia tried to achieve united opposition to British policies. Shortly after the passage of the Stamp Act, the Stamp Act Congress was convened.

During the fifteen years that the Continental Congress met, Charles Thomson served as its secretary.

First Continental Congress[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see First Continental Congress.

Leaders such as Adams argued that there must be a general government to regulate trade, to prevent civil war among the colonies, and to suppress internal dissension. Nothing was done. 55 delegates represented twelve of the Thirteen Colonies (Georgia did not send a representative). This body debated over what the colonies should do, if anything, in reaction to the Intolerable Acts passed by Parliament that year. With the passage of the Continental Association, the First Continental Congress successfully boycotted British goods coming into the colonies, drastically reducing imports. It agreed that a Second Continental Congress should meet in 1775.

Second Continental Congress[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see Second Continental Congress.

The Second Continental Congress is by far the more noteworthy of the two. It was the national government that conducted the war, controlled the army, raised money, conducted diplomacy and formed alliances, and finally (in 1783) made peace with Britain.

Trouble brewed in Boston where the British army, opposed by colonial Minute Men, had marched on Lexington and Concord. An outpouring of militia trapped the British in Boston, and Congress took control of them, appointing one of their members Colonel George Washington of Virginia as commander in chief "of all the continental forces, raised, or to be raised, for the defense of American liberty." For the next six years Congress became the national government.

The Second Continental Congress, called by the First Continental Congress, convened in Philadelphia, May 10, 1775, adopting the name the "United Colonies." Fighting had begun and the Americans had trapped a major British army in Boston. The failure in Sept. 1775 of the "Olive Branch Petition" of conciliation with Britain convinced the members of Congress that there was no turning back.

During the course of the Congress leading up to war with Britain in 1776, three important and separate committees were created: the first committee drafted the Model Treaty, the second drafted the Articles of Confederation, and the other drafted the Declaration of Independence.

On September 9, 1776, the Continental Congress voted to change the name of the country to the "United States of America".

Congress of the Confederation[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see Congress of the Confederation.

The Congress of the Confederation, which was viewed as an extension of the earlier Continental Congresses, met from 1781 to 1789.[2]

New nation[edit]

After expelling the British from all 13 colonies in spring 1776, Congress called on each to set up a state government. Convinced by Thomas Paine that there was no further need for a king, the Congress unanimously approved independence and issued the Declaration of Independence in July 1776, announcing a new nation had been formed on July 4.

With war underway urgent problems of organization, procedure, and policy prevented adjournment. Battles at Crown Point, Ticonderoga, and Bunker Hill requires a central authority to supervise the war. Washington's success in forcing the British evacuation of Boston on March 17, 1776, tended to give force and direction to this sentiment and to make it doubly apparent that only by arms could the prized liberties be preserved.

One of the first acts was "to prepare a plan of treaties to be proposed to foreign powers." This "Plan" served as the model for a critical treaty with France negotiated by Benjamin Franklin in 1777-78 after the capture of an invading British army at Saratoga. France not only provided money and munition, it declared war on Britain and turned the American Revolution into a world war.

Congress authorized the "Continental Army" giving it a force directly under its control; Washington gave it a national vision and a national mission, overcoming localism and regional demands. Lacking the power to tax, Congress undertook to finance the war by its own letters of credit, but when these bills began to depreciate and Congress called on the states for aid there was grumbling and discord.

Immediately after the Declaration, Congress drafted the Articles of Confederation. It went into effect in 1777 but was not finally ratified in 1781. After a four month long Constitutional Convention and ratifying conventions in all 13 states, the Articles were replaced by the much more powerful Constitution in 1789.

In 1778 the government of Britain organized the Carlisle Peace Commission to try to negotiate terms.

National capital moves around[edit]

The British advance on Philadelphia compelled Congress in mid-December 1776, to flee to Baltimore. When the British pulled out it returned to Philadelphia in March 1777. In September, Congress was again forced out, going to Lancaster and then York, Pennsylvania, where it remained until the British left Philadelphia in June 1778. In June 1783, Congress left Philadelphia because of the mutiny of Pennsylvania militia, this time going to Princeton, New Jersey, until Nov. 4, 1783, then to Annapolis, Maryland and in 1784 to Trenton, New Jersey. It moved to New York City in early, 1785, and remained until it closed its books in 1789.

Peacetime[edit]

The serious fighting ended in 1781 when Washington captured the main British combat army at Yorktown. The British garrison army in New York City (and a few other places) remained until the peace treaty took effect in late 1783.

The peacetime Congress had to grapple with large issues, especially the national debt and the huge western territories between the settled Atlantic seacoast and the Mississippi River.

National debt[edit]

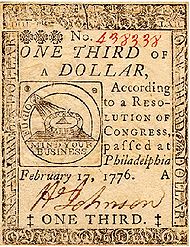

During the war Congress printed paper money called "Continentals". Due to economic warfare conducted by the British, Continentals soon became worthless—indeed, any worthless thing was said to be "not worth a continental."

By the end of the war the national government had foreign debts of $8 million (mostly to French and Dutch bankers), and debts to Americans amounting to $42 million. Annual interest payments were $2.5 million. The Congress had no taxing powers, and the states were reluctant to give it money. It borrowed more from Europe. The best solution was to sell land.

Western lands[edit]

Sales of western lands could provide the national government with needed revenue without asking he states, while also facilitating western settlement. The challenge was to get the land from the states. In 1776 seven states had overlapping and conflicting claims to western lands that were based on old royal grants and charters. Virginia had the largest claim, which included the present states of Kentucky and West Virginia, and parts of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois. Cutting across Virginia's northwestern claims were the claims of Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York. South of Virginia were the claims of North Carolina (claiming Tennessee) and South Carolina and Georgia, which claimed the lands between their western boundaries and the Mississippi. The ownership of such vast areas by a few states aroused jealousy and ill-feeling among the six smaller states that had no western lands. Maryland refused to ratify the Articles until the landowning states surrendered their claims to the new government.

The Continental Congress successfully urged the states to cede their land claims to it and promised that the territory so ceded would be erected into new states having full equality with the old. New York and Virginia ceded their claims in 1781 and 1783. Virginia ceded its lands in Ohio on condition of being allowed to reserve for itself the Military District between the Scioto and Little Miami rivers to satisfy military grants made during the Revolution. Virginia also retained its land south of the Ohio, which became the state of Kentucky in 1791. In 1785 Massachusetts ceded its claim to a belt of land extending across the present states of Michigan and Wisconsin, and in the following year Connecticut ceded its western lands. Connecticut reserved to itself a tract of 3.8 million acres in northeastern Ohio—called the Western Reserve—a part of which was set aside for the relief of Connecticut sufferers whose property had been destroyed by the British during the Revolution. The remainder was sold to the Connecticut Land Company. South Carolina ceded its narrow strip of land in 1787, and North Carolina transferred its western lands in 1790. All the land in Kentucky and Tennessee had already been granted to revolutionary war veterans, settlers, and land companies so the national government received no land but only political jurisdiction.

These cessions of 222 million acres of western lands gave to the national government a vast public domain in which it owned the land and over which it had governmental jurisdiction. In 1785 a land ordinance provided a method of selling the lands. In 1787, in response to demands of the Ohio and Scioto land companies, which were negotiating for the purchase of large tracts of land north of the Ohio, the Northwest Ordinance was adopted to provide a form of government for what came to be known as the "Old Northwest." The Ordnance, written by Thomas Jefferson, provided for an elaborate survey that created the checkerboard land pattern still in use, and provided that no slavery was allowed there during the territorial stage.[3]

Sermons preached in front of the Congress[edit]

In 1774, Jacob Duché led the Congress in a well known sermon while reading Psalm 35.[4] William Gordon also addressed the Congress.[5]

One member of the Continental Congress, Silas Deane, said of Duché:

The Congress met, and opened with a Prayer made by the Rev. Mr. Deshay [Duché] which it was worth riding one hundred miles to hear. He read the Lessons of the day, which were accidentally extremely applicable, and then prayed without book about ten minutes so pertinently, with such fervency, purity and sublimity of style and sentiment, and with such an apparent sensibility of the scenes and business before us, that even Quakers shed tears. The thanks of the Congress were most unanimously returned him by a select honorable committee.[6]

Further reading[edit]

- see Bibliography of the American Revolution

- Journals of the Continental Congress, From September 5, 1774, to December 31, 1776, inclusive

References[edit]

- Blanco, Richard L., ed. The American Revolution, 1775-1783: An Encyclopedia. 2 vol. Garland, 1993. 1857 pp.; 800 articles by 129 experts

- Faragher, John Mack, ed. The Encyclopedia of Colonial and Revolutionary America. 1990.

- Fremont-Barnes, Gregory, and Richard A. Ryerson, eds. The Encyclopedia of the American Revolutionary War: A Political, Social, and Military History (ABC-CLIO, 2006) 5 volume paper and online editions; 1000 entries by 150 experts, covering all topics

- American Revolutionary War: A Student Encyclopedia (5 vol. 2006), shorter version, 800 articles

- Greene, Jack P. and J. R. Pole, eds. A Companion to the American Revolution (2nd ed. 2004) 778pp. 90 excellent essays by experts

- Purcell, L. Edward, ed. Who Was Who in the American Revolution. (1993).

Surveys[edit]

- Ferling, John. Almost A Miracle: The American Victory in the War of Independence (2009) excerpt and text search

- Higginbotham, Don. The war of American independence: military attitudes, policies, and practice, 1763-1789(1971) best scholarly overview of military affairs; online through ACLS History E-Book

- Jensen, Merrill; The New Nation: A History of the United States during the Confederation, 1781-1789 (1950), a standard scholarly survey

- Lancaster, ed. Bruce. The American Revolution (American Heritage Library) (1985), heavily illustrated

- Miller, John C. Triumph of Freedom, 1775-1783 (1948) online edition

- Morris, Richard. The Forging of the Union, 1781-1789 (1788), a standard scholarly survey

- Nevins, Allan. The American States During and After the Revolution, 1775-1789 (1923)

- Rakove, Jack N. The Beginnings of National Politics: An Interpretive History of the Continental Congress (1979)

Primary sources[edit]

- Commager, Henry Steele, and Richard Morris, eds. The Spirit of 'Seventy-Six: The Story of the American Revolution as Told by Participants (1967); excellent collection of primary sources

- Morison, S. E. Sources and Documents Illustrating the American Revolution, 1764-1788, and the Formation of the Federal Constitution (1923) online edition

References[edit]

- ↑ The American Revolution: A Historical Guidebook

- ↑ Congressional Dynamics: Structure, Coordination, and Choice in the First American Congress, 1774-1789

- ↑ Benjamin Horace Hibbard, History of the Public Land Policies (1965)

- ↑ America's Founding Fathers and the Bible: A Select Study of America's Christian Origin

- ↑ A sermon preached before the House of representatives, on the day intended for the choice of counsellors

- ↑ S. Deane to Elizabeth Deane

first continental congress prayer[edit]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RwkTYFk3HSw

george washington

john adams

samuel adams

john jay

patrick henry

peyton randolph

Jacob duche an Anglican minister of christ church this was the chaplin

the province of Massachusetts Bay is mentioned in this video.

External links[edit]

| |||||||||||

Categories: [United States History] [American Revolution]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/15/2023 14:45:32 | 22 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Continental_Congress | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF