Japan

From Rationalwiki

From Rationalwiki

“”The Japan of old still dwells deep in the soul of every inhabitant of her islands and manifests itself at every turn in some euphuistic subtlety or an exquisitely delicate courtesy.

|

| —Louis-Frédéric Nussbaum, French historian[1]:161 |

The State of Japan (日本国 Nippon-koku or Nihon-koku, either is correct)

is an East Asian archipelago nation on the westernmost edge of the Pacific Ocean, and the object of much misplaced admiration by naive Westerners. Its four main islands are Hokkaido, Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu. It is the world's last nation to have an emperor as its leader, although that emperor is bound by constitutional restrictions to the point where he is essentially a figurehead. Similar arrangements persisted for much of Japan's history, but it is clear that the imperial Yamato dynasty has proven to be remarkably resilient and long-lived. Today, Japan is known for its technological innovation, excellent food, and unique blending of Western and Eastern cultures. Its capital and largest city is Tokyo.

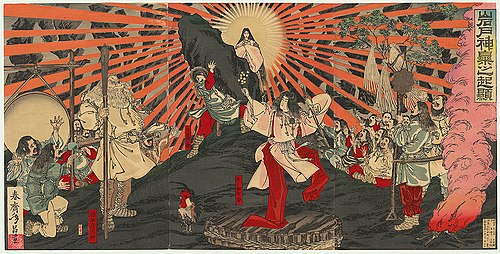

Japan started showing up in Imperial China's writings as early as the 1st century CE, and sometime around the 3rd century, it became unified under an imperial government. The most influential of Japan's early clans, the Yamato, became the ruling dynasty during this period and started to claim descent from Amaterasu![]() , Japan's traditional sun goddess.Court life in Japan was heavily influenced by their Chinese neighbors, but the emperor himself increasingly retreated into personal pursuits while allowing court officials to rule Japan in his stead. This first created an effective hereditary regency led by powerful court families, but these court families themselves soon lost interest in day-to-day administration. In their place rose a succession of military dictators (shōguns), feudal lords (daimyō), and a class of warrior nobility (samurai). The warlords fought amongst themselves for land and power during a bloody period of constant civil wars called the Sengoku Jidai, or the "Age of Warring States." Japan wouldn't reunify until the rise of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603. During the Sengoku era, though, traders from Europe showed up to exploit the wars for profit. The Tokugawa retaliated by implementing the Sakoku policy, which forced Japan into two centuries of isolationism, peace, and stagnation.

, Japan's traditional sun goddess.Court life in Japan was heavily influenced by their Chinese neighbors, but the emperor himself increasingly retreated into personal pursuits while allowing court officials to rule Japan in his stead. This first created an effective hereditary regency led by powerful court families, but these court families themselves soon lost interest in day-to-day administration. In their place rose a succession of military dictators (shōguns), feudal lords (daimyō), and a class of warrior nobility (samurai). The warlords fought amongst themselves for land and power during a bloody period of constant civil wars called the Sengoku Jidai, or the "Age of Warring States." Japan wouldn't reunify until the rise of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1603. During the Sengoku era, though, traders from Europe showed up to exploit the wars for profit. The Tokugawa retaliated by implementing the Sakoku policy, which forced Japan into two centuries of isolationism, peace, and stagnation.

Everything changed in 1854 when a modern war fleet from the United States showed up to threaten Japan into reopening trade. Western trade had an explosive effect on the Japanese economy, and disgruntled samurai launched the Boshin War in 1868 to destroy the shogunate and return power to the emperor. Emperor Meiji embarked on a bold series of modernization and industrialization reforms which rapidly transformed Japan from a feudal state into a modern military force. Emboldened by its new military, Imperial Japan started throwing its weight around. It made inroads into Korea, beat China in a war, beat Russia in a war, allied with the British Empire, and then started bullying China even harder during and after World War I. This age of imperialism culminated in Japan's re-invasion of China in 1937, kicking off the Second Sino-Japanese War. During this campaign, Japan's horrific brutality and war crimes earned condemnation and sanctions from much of the world. This placed Japan in a desperate economic situation, leading it to attack Pearl Harbor and various European colonies in 1941, bringing Japan into World War II on the side of the Axis. Japan did even more horrible things in that war until 1945, when the US dropped two nuclear bombs on Japanese cities, compelling the nation's emperor to surrender near-unconditionally.

After the destruction of the war and subsequent military occupation, Japan rebuilt itself on the principle that it should make cars and electronics, not war. Japan's new constitution stripped the emperor's divinity and basically all power and forever renounced Japan's right to declare war. In the absence of military adventurism, Japan focused on building its economy and became a major market force through the latter 20th century, although economic stagnation became to set in after the 1990s until today. Although Japan seems like a more friendlier nation on the global stage than it was during the imperialist age, there are still echoes of that dark past. A de facto one-party state under the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), Ultranationalism is a major force in Japanese politics. Its former prime minister Shinzō Abe seemed to have his heart set on undermining the constitution and returning to the good old days when Japan could use its military offensively again.[2] After he was assassinated for his links to the Unification Church cult, he became a martyr among far-right revisionist organizations, and the LDP has echoed that they would implement Abe's policies which was not realized when he stepped down. Japan has also refused to deal with the crimes its soldiers and government committed during the imperial age, a major sticking point with Japan's neighbors and allies.[3] Japan's largest conservative political organization, Nippon Kaigi, has made it its goal to stoke ultranationalism and revise history to rebuild Japan's empire.[4]

History[edit]

Mythological founding (and actual history)[edit]

According to Japan's Shinto traditions, the gods created the Japanese islands. Alongside the Japanese islands came kami, which were nature deities influencing various natural phenomena.[5] The most important of the kami was Amaterasu, the sun goddess who holds the forces of evil at bay with her presence.[6] She essentially serves as the patron deity for all of Japan. That red circle on Japan's flag is a sun representing her. Japan's legends hold that Amaterasu created Japan as a nation and is the direct ancestor of the ruling Yamato dynasty.[7] Ever since the codification of this legend, Japan has heavily associated itself with the sun and its imagery.

So that's Japan's mythic origin story. Of course, we here at RationalWiki are at least a little bit skeptical of sun goddess stories, so we'll also give you the accepted history. In reality, Japan started off as a collection of disunited peoples considered unimportant by the nearby Chinese empire.[8] Although generally disinterested in Japan as a potential tributary, Chinese travelers documented much of the region's early culture. They described ancient Japan as a land of hundreds of scattered tribal communities that subsisted on raw vegetables, rice, and fish served on bamboo and wooden trays, had vassal-master relations, collected taxes, and had provincial granaries and markets, violent succession struggles, and formed political alliances and federations.[9] During that early period, Japan was influenced by visiting travelers from China. Japan's remote situation meant that its rulers could pick and choose which customs and traditions to adopt and which to ignore. Japan eventually adopted Chinese-style writing (kanji) and architecture, and the evolution of these practices was also often inspired by happenings in China.[10]

Around the 5th century, a kingdom ruled by the Yamato dynasty rose to power by unifying most of what is now Japan. During the 7th century, those Yamato rulers got word of China's extensive written histories. Deciding to give that a go themselves, the Yamato commissioned an official chronicle of myths, history, and legends. The Kojiki, as it's now known, mainly served to dictate Japan's "canon" history and justify the Yamato dynasty's imperial rule by connecting them to Japan's mythological founding.[11] And when we say the Kojiki was legal canon, we mean it. Scholars who questioned the work's accuracy faced censorship, forced resignation, or were even brought to trial on criminal charges.[12] Indeed, the Japanese founding myth is less mythology or history than outright propaganda. The Yamato had brilliantly manipulated Japanese beliefs to create for themselves a divine right to rule.

Early Yamato rule[edit]

During the rise and consolidation of the Yamato state, Japan started developing an aristocratic society whose elites were expected to be skilled soldiers.[13] This aristocracy was divided into many powerful clans, each headed by a patriarch and sworn to serve the emperor. It was essentially Japan's take on feudalism.

Around 538 CE, Chinese Buddhism crossed into Japan and was quickly adopted by many clans and Yamato emperors.[14] The emperors also started modeling their rulership style after Chinese Confucianism, mainly where fiscal policy and central banking were concerned. Based on the Chinese model, the Yamato emperors built an elaborate court life where subordinate clan patriarchs would help the emperor administrate Japan. Like China, Japan had no fixed capital during this period, as the emperor could move his court wherever he pleased.

The common people weren't lucky enough to benefit from this lavish lifestyle. The Yamato gradually appropriated most of Japan's land under direct imperial rule and organized the population according to their professions, which they were stuck with for life.[13] Most people were farmers; others were fishers, weavers, potters, artisans, armorers, and ritual specialists.

In 645, the process of imperial centralization got a huge shot in the arm with the Taika reforms. Inspired by some bloody infighting among the clans, the Taika reforms placed all Japanese land under the personal ownership of the emperor. They instituted a census upon which a new tax system would be built.[15] Much of this was meant to emulate the success of the Tang dynasty in Imperial China, and Japan built government bureaus and trained officials in the Chinese way.

To further solidify itself as an empire, Japan built itself a permanent capital city at Heijokyo, or Nara, in 710. The new city was styled after the Tang dynasty capital at Chang'an and had around 200,000 people.[16] Although economic activity around the capital was hopping, the emperors' focus on their capital caused things to stagnate elsewhere. Due to pushback from nobles and Buddhist monks, the Taika reforms were eventually abandoned.[17] In the reform's place rose a system of large noble estates, which gradually became increasingly autonomous from imperial rule.[16] Factional infighting and court intrigues consumed most of the emperor's time and energy, and power started to decentralize.

In a last-ditch attempt to reverse decentralization, some Yamato emperors tried moving the capital around. They moved in 784 to Nagaoka and in 794 to Heian. The latter city would eventually become known as Kyoto, its name ever since.

Fujiwara regency[edit]

Moving the capital to Kyoto did indeed reinvigorate the imperial government. However, a series of wars in northeastern Japan against unsubjugated peoples necessitated the appointment of a chief commander, the seii taishogun.[18] The clans also became more powerful as their military abilities were called into action. As a result, the nobles completely disregarded many of their obedience and tax obligations with basically no consequence.

More noble knife-fighting ensued and one noble family, the Fujiwara, became the dominant political force in the imperial court. Members of the family intermarried into the Yamato dynasty, ensuring that the Fujiwara would always be able to influence where and how the emperor's time and money were spent.[19] Eventually, they leveraged that influence to manipulate the imperial succession by placing the youngest possible candidate on the throne. They ensured that the child emperor would need a regent to rule and that regent would always be a member of the Fujiwara clan. In this manner, the Fujiwara had neatly side-stepped the imperial myth to seize power without actually needing to remove the Yamato dynasty.

To keep the emperor and other nobles from protesting at this blatant usurpation, the Fujiwara made it their policy to distract everyone in court with frivolous pursuits. The aristocracy busied themselves with poetry, artwork, and the finer things in life.[18] During this period, the Japanese written language began to differentiate itself from Chinese. Japanese noblewomen wrote elaborate works describing semi-fictionalized accounts of court life and romance, most notably The Tale of Genji.![]() Many of these works are now counted in the canon of classical Japanese literature. Meanwhile, the Fujiwara and other clever clans used the lack of imperial oversight to acquire vast amounts of land and wealth for themselves.

Many of these works are now counted in the canon of classical Japanese literature. Meanwhile, the Fujiwara and other clever clans used the lack of imperial oversight to acquire vast amounts of land and wealth for themselves.

Rise of the warlord class[edit]

The Fujiwara eventually started to fail in the early 1000s due to the emergence of factions within the clan and subsequent power struggles. Opposition Fujiwara factions also hired private, professional armies of samurai, which they used to fight giant pissing contests.[20] The Fujiwara eventually tore each other apart, making way for rival clans Minamoto and Taira to fight a vast civil war between 1180 and 1185 over control of the regency.[21] The Minamoto won out due to their superior military strength, and Minamoto no Yoritomo used his newfound power to declare himself military dictator and create the first bakufu or shogunate.[22]

Minamoto no Yoritomo also invented the office of shugo. The shogun appointed a shugo to rule one or more provinces in his name. Upon the shugo's death, a successor would be appointed by the shogun without regard to familial succession.[23] The shugo, as you might expect, immediately decided to start treating the land as their personal property. They raised their own samurai armies using the profits from their granted holdings, and they quickly became too numerous and powerful for the shogunate to control.[23] By the 1400s, the shugo decided to start completely ignoring the shogun's authority. They became the daimyō, lords in their own right who ruled as they chose.

One of the most critical events speeding along the rise of the warlord era were the two invasions by Kublai Khan and the Mongol Empire in 1274 and 1281. Japan's shogun rejected the Mongol demands, raised an army of samurai, and defended Kyushu against two Mongol invasions, eventually thwarted by typhoons. Shinto priests attributed the two defeats of the Mongols to a "divine wind" (kamikaze), a sign of heaven's special protection of Japan. The daimyō, though, were convinced that their way of warlordism and samurai honor codes was the key to protecting Japan.[24] They continued grasping up more and more power, now having decided that they were doing it for the good of Japan as a whole.

This process was completed in 1467 when a succession dispute led different clans to fight against each other for the shogunate. The Ōnin War![]() , a nationwide free-for-all melee, lasted for a decade, devastating Japan and leaving many of the daimyō militarily exhausted but entirely beyond the shogun's control. It also permanently set the daimyō against each other, creating a situation in which Japan would remain in a low-intensity civil war for more than a century afterward.

, a nationwide free-for-all melee, lasted for a decade, devastating Japan and leaving many of the daimyō militarily exhausted but entirely beyond the shogun's control. It also permanently set the daimyō against each other, creating a situation in which Japan would remain in a low-intensity civil war for more than a century afterward.

Sengoku period[edit]

“”Most of the leading samurai families took part in what can only be described as an orgy of violence, burning of temples, ransacking shops, massacring hostages, and defiling the dead.

|

| —J. L. Huffman, historian.[25] |

The Onin War led to serious political fragmentation; a great struggle for land and power ensued among daimyō, plunging Japan into constant violence. Most wars of the period were short and localized, but they happened all over the country, and new wars started constantly. This had a catastrophic effect on Japan's economy. Near Kyoto, the shogunate could maintain security, but the non-stop movement and clashes of armies strained local resources elsewhere.[26]

To support these constant wars and the construction of new forts and castles, the daimyō oppressed and taxed their peasants even harder. The peasants didn't take well to that, and many revolted to form Ikki. The Ikki were armies of rampaging peasants who started by sacking and destroying their overlords' possessions and then evolved into regional protection rackets.[27] One powerful peasant group took over Kyoto itself, cutting the city off from the outside world and ignoring the shoguns' legal authority.

During this tumultuous time, Europeans started showing up to establish trade relations. First came Portugal in 1543, then Spain in 1587, followed by the Netherlands in 1609. In exchange for Japanese gold and silver, the Europeans started selling firearms and information on how to use them. This had a dramatic effect when warlord Oda Nobunaga adopted firearm technology around 1560 and used these new tactics to conquer a vast chunk of Japan and become the country's new leader, taking the first step towards unification.[28] His greatest victory was the Battle of Nagashino, where he and his ally Tokugawa Ieyasu used firearm tactics to destroy a samurai cavalry charge.[29] That had a permanent impact on Japanese warfare, as warlords realized that guns trumped the old ways of war. The samurai was on his way out.

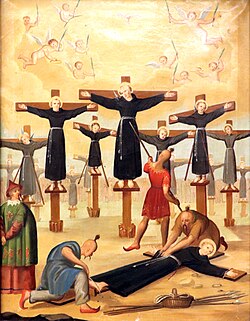

Another impact of European trade made itself known not too long after. European missionaries did their thing basically unhindered during the struggle, spreading Christianity to hundreds of thousands of converts. As Japan started unifying, though, the daimyō were able to start putting a stop to this. Proscriptions against Christianity began in 1587 and outright persecutions in 1597.[26] One notable event saw the rulers of Nagasaki execute 26 Catholics via crucifixion. Suppressing missionary activity would become one of Japan's motivations for completely severing contact with the outside world.

Reunification process[edit]

Oda Nobunaga would later be betrayed by one of his generals and forced to commit suicide. His close second-in-command Toyotomi Hideyoshi took over the conquests, creating the second step towards unification by turning Japan into a patchwork realm built on alliances.[30] Hideyoshi fucked up, though, by trying to invade Korea, which was a tributary state under Chinese domination. He started the effort in 1592, but it quickly went sour in the face of huge Chinese armies. The wars ended abruptly in 1598 with his death.

In the place of the first two great unifiers came the third and last: Tokugawa Ieyasu, their former ally. After his old friend's death, he quickly seized control of Japan, aided by the vast wealth and land area he had amassed during the Sengoku campaigns. By 1600, Tokugawa had defeated all of the rebellious warlords and brought the entirety of Japan under his personal control. He rapidly abolished numerous enemy clans, reduced many others in size, and redistributed the spoils of war to his family and allies.[31]

Once his rule was indisputable, Tokugawa took on the title of shogun, legitimizing himself as the ruler of all of Japan. This marks the beginning of the Tokugawa Shogunate and the end of the Sengoku period and its wars.

Tokugawa Shogunate[edit]

Tokugawa's first task as a shogun was to deal with the rising problem of Christianity within Japan. In 1612, he ordered his direct vassals to swear never to adopt the religion, and he spent the next few decades gradually restricting European traders to just a few cities.[32] In 1635, this policy of seclusion became even more extreme, with an edict forbidding any Japanese person from ever leaving the country.

By this point, Japan had about 720,000 Christians.[33] Tokugawa feared that the nearby Spanish, who had recently taken over the Philippines, would use Christianity as a way to force colonial rule on Japan.[33] To prevent that, he outright banned Christianity, beginning a horrifying process where tens of thousands of Christian converts were beheaded or tortured to death.[33]

The Christians didn't take that lying down. In 1637, they launched the Shimabara Rebellion. The Tokugawa failed to suppress the rebellion even after sending in more than 120,000 soldiers, so they had to hire help from the Dutch. Once back in control, Tokugawa officials ordered the execution of about 37,000 rebels. The uprising confirmed to many Japanese that Christianity meant disloyalty and effectively spelled the end of that religion's chances of making significant headway in Japan. By 1641 Japan had expelled almost all foreigners save the Dutch and Chinese and limited even them to just the city of Nagasaki.[32]

Meanwhile, Tokugawa had enforced a strict Confucian-inspired social hierarchy on the people of Japan. At the top were the samurai, who were just 7% of the population; they levied taxes on farmers and were the only class legally permitted to bear weapons.[34] Peasants were second, as the Japanese acknowledged that farmers and laborers performed an essential service to society.[35] Then came artisans who produced non-essential goods, restricted to their own quarters in every city. At the very bottom were merchants, who had wealth but were forbidden from showing it. Finally, below the very bottom were the untouchables, people who were stuck doing jobs Japan considered shitty, like being a tanner or an undertaker.[36] Untouchables were carefully sectioned away from the rest of society until they were needed for some reason.

Even in a single household, there were enforced restrictions. Absolute obedience was demanded from family members toward the head of household (kachō), and women were officially held in contempt.[34]

Perry Expedition and the Bakumatsu[edit]

Throughout the early 1800s, Westerners became more and more determined to trade with Japan. Western ships routinely docked at Japanese harbors without permission, trespassed on Japanese territorial waters, and offloaded Western merchants to do some down-low buying and selling.[37] Meanwhile, the Tokugawa Shogunate was in crisis due to many natural disasters and the inability to deal with the resulting fallout. Merchants and bankers, after all, were considered scum in Japan at the time.

Meanwhile, the United States had just annexed California in the Mexican-American War and was looking to capitalize on having a Pacific port by throwing some weight around in the Pacific. China was first on the menu, but Japan wasn't far behind. In 1852, Matthew Calbraith Perry, who commanded the US East India Squadron, received orders from President Millard Fillmore to take his fleet to Japan and use gunboat diplomacy to get the Japanese to allow trade with the US.[38] The US had tried this move before on multiple occasions, but Perry realized that the key to success was to perform a suitably intimidating show of military might.[39]

Perry started in 1853 with a dry-run in Okinawa (then part of the Ryukyu Kingdom,![]() effectively a tributary state of Japan). He parked his warships near the islands and refused to meet with anyone save the island's lead official.[39] After getting the Okinawans to cave, Perry ignored their objections and moved on to Japan itself. His fleet arrived in Tokyo Bay a month later, fired a few heavy artillery salutes, and refused to meet with anyone save the emperor.[39] After two weeks of this standoff, the Japanese finally sent their emperor to meet with the aggressive new threat. Perry gave the emperor letters of friendship from President Fillmore and what was basically an advertisement for trade with the US. The Japanese only ordered him to leave. He complied but returned a year later with eight ships and many soldiers.[38] After about a month of negotiation and threats, Perry got the Japanese to agree to the Treaty of Kanagawa, which opened Japan to trade and provided shipwrecked Americans care.

effectively a tributary state of Japan). He parked his warships near the islands and refused to meet with anyone save the island's lead official.[39] After getting the Okinawans to cave, Perry ignored their objections and moved on to Japan itself. His fleet arrived in Tokyo Bay a month later, fired a few heavy artillery salutes, and refused to meet with anyone save the emperor.[39] After two weeks of this standoff, the Japanese finally sent their emperor to meet with the aggressive new threat. Perry gave the emperor letters of friendship from President Fillmore and what was basically an advertisement for trade with the US. The Japanese only ordered him to leave. He complied but returned a year later with eight ships and many soldiers.[38] After about a month of negotiation and threats, Perry got the Japanese to agree to the Treaty of Kanagawa, which opened Japan to trade and provided shipwrecked Americans care.

First contact with the US and the subsequently forced renegotiations for more concessions over the next five years prompted a general Japanese discussion over dealing with the new threat of an industrialized outside world. It was clear that the old Japan could not defend itself from a modern Western power. In 1855, the Japanese turned to the Dutch for help, opening Dutch military schools and purchasing outdated Dutch warships.[37] Still, Japan's ascendance was slow and more economical and trade concessions were forced upon it by other Western powers. Opposition to this rapid reform ushered in a period of political chaos. Today, the period is known as the Bakumatsu, literally meaning "end of the shogunate." Uncontrolled trade with the West destroyed Japan's economy, as its artisans and peasants couldn't compete with industrially-produced Western goods.[40] Those parts of Japan that resisted Western influence came under attack by Western allied forces. The most significant example of this was the Shimonoseki campaign of 1863, where the British Empire, France, Russia, the Netherlands, and the United States teamed up to force control over the straits between Kyushu and Honshu.[41]

Boshin War[edit]

The conflict became inevitable in 1868 when the young Emperor Meiji started flexing his political muscles, convinced that Japan needed to evolve to meet the times without the hampering influence of the shogunate. The emperor forced Tokugawa Yoshinobu to resign from the shogunate and then stripped him of his titles and lands.[42] Yoshinobu, who was to be the last shogun, marched to the emperor's palace at Kyoto with his personal army, ostensibly to voice his objections. By most accounts, Yoshinobu wasn't looking for a fight, but a rival clan caught him near the capital and attacked.[42]

That first battle set off a chain of events where the Tokugawa and the emperor declared war on each other. The emperor had been politically irrelevant for so long that many of the shogun's soldiers didn't recognize the imperial banner during the first few clashes.[42] The imperial forces generally won these fights due to their greater usage of modern military technology. The emperor's seeming invulnerability in battle convinced many powerful daimyō to switch sides in the conflict. The emperor's revered place in Japanese culture meant that he generally had the support of the Japanese people.

Saigo Takamori, later famed as the "Last Samurai," led imperial troops to surround the city of Edo (old Tokyo) in 1869, forcing the shogun to surrender.[43] The shogun's navy fled north to Aizu in northern Japan, but the imperial faction managed to suppress this last defiance in one final battle. The city of Edo was later renamed Tokyo, meaning "eastern capital."

Meiji modernization[edit]

“”♫Imperial force defied, facing 500 samurai,

♫Surrounded and outnumbered, 60 to 1 the sword face the gun! |

| —Sabaton, "Shiroyama".[44] |

With Emperor Meiji in complete control of Japan, he launched a far-reaching series of reforms. First, he abolished the old social order, notably casting aside the samurai class and declaring them equal to other citizens.[45] He then established Western-style military academies to train a professional army. Gone were the samurai and the sword; soldiers would be conscripted, and they would use guns and cannons to win the day. Most importantly, Japan industrialized with truly shocking speed. Merchants and businessmen were elevated from the bottom of society to the top. The government assisted them in forming huge corporations to produce iron, steel, ships, railroads, and other heavy industrial goods.[45] In addition, he began aggressive efforts to assimilate the Ainu people![]() , first in Hokkaido and later in southern Sakhalin (unfortunately for the Ainu, this was the only half of Sakhalin they inhabited) and the Kuril Islands; this eventually resulted in the near-total destruction of their culture and rendered their language all but dead. Despite laws formally recognizing Ainu identity and funding cultural research and revival, many Ainu face vicious discrimination in everyday life.

, first in Hokkaido and later in southern Sakhalin (unfortunately for the Ainu, this was the only half of Sakhalin they inhabited) and the Kuril Islands; this eventually resulted in the near-total destruction of their culture and rendered their language all but dead. Despite laws formally recognizing Ainu identity and funding cultural research and revival, many Ainu face vicious discrimination in everyday life.

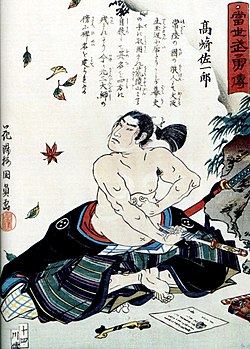

This total societal upheaval didn't happen without resistance. Satsuma clan samurai Saigo Takamori, previously an instrumental player in the Boshin War for the imperials, turned against the new government when it started centralizing the country at his family's expense.[46] In 1877, he led a samurai uprising, the Satsuma Rebellion, which became the old ways' last gasp against the new modern era. The samurai fought valiantly against long odds, and in the end, most of them committed suicide rather than surrender. Although that event spelled the end of the samurai era, Saigo Takamori, the "Last Samurai", became a hero to the Japanese people.[46] The samurai code of honor (bushidō) and their refusal to surrender became integral parts of Japanese military culture.

After all of that, the emperor decided that he needed to strengthen his position in the eyes of the people. In 1889, the emperor promulgated a new constitution based on the German Empire's model, which created a parliament and prime minister but still reserved effective power for the emperor.[47] He then established the Office of Shinto Worship to reshape Japan into a society built around the emperor's godlike status.[48]

The Red Sun rises[edit]

Economic and cultural modernization was all well and good, but the emperor and many Japanese officials also decided that they needed to completely rethink Japan's place among other nations. To escape the fate of colonized and brutalized Asian nations, Japan would need to emulate the West by becoming its own imperial power.

First Sino-Japanese War[edit]

The first test of Japanese imperialism was naturally Korea. Japan had historically been preoccupied with Korea due to its proximity to the Home Islands (as well as the historical memory of having lost the first invasion of Korea in 1592-1598), and Japan spent the 1880s dueling with China for diplomatic influence in the peninsula.[49] The different approaches Japan and China took toward meeting the demands of a modern world soon became apparent. While Japan hastily adopted new technologies and ways of thinking, the Chinese Qing dynasty simply entrenched itself further in tradition and conservatism.[50]

By 1894, Japan had realized that its modern military was ready to kick the Chinese ass, and Japan's resulting imperiousness and stubbornness in dealing with the Korean dispute touched off the inevitable First Sino-Japanese War. Although Western onlookers predicted an easy victory for China's huge army, the better-equipped Japanese force quickly scored rapid victories.[50] China's military was also hampered by corruption, most notably by Empress Dowager Cixi, who had siphoned military funds to build herself a giant palace.[51] China also lacked support from its own populace, as the Qing dynasty's corruption and neglect of its duties didn't do much to inspire Chinese patriotism.[52]

By 1895, the Japanese had overrun Korea, made their way into Manchuria, and threatened to take Beijing itself.[50] The Chinese had no choice but to sue for peace, abandoning Korea and ceding Taiwan and the Liaodong Peninsula to Japan.[53] Although Japan was later threatened by other Western powers to hand back Liaodong, this marked the first great expansion of what was to become the mighty Japanese Empire.

Russo-Japanese War[edit]

Japan's dominion over Korea still didn't go without challenge, as Russia also hoped to expand its holding southward into Asia to gain more warm-water Pacific ports. The British Empire also had a vested interest in keeping the Russians out of the Pacific, so the two powers signed a treaty of alliance in 1902.[49] That treaty stipulated that Japan would have to fight Russia alone, but the British would intervene if Russia managed to call another European power against Japan. That agreement allowed the British to threaten Russia and still be able to focus elsewhere in Asia.

In 1904, Japan ordered Russia to withdraw its troops from Manchuria to get them away from Korea. When Russia failed to meet the demand of the upstart Asian nation, Japan attacked. Without declaring war, the main Japanese fleet assaulted the Russian Pacific fleet in its leased Chinese port on the Liaodong Peninsula (Port Arthur), inflicting heavy damage.[54] Launching a surprise attack on a fleet in port? Have we heard that story before?

With Russia's only Pacific naval forces either bottled up in port or sunk, the Russian land force was cut off from aid or supply. Japan's army launched a series of attacks against the Russian troops in northern Korea, pushing them back into Manchuria, where they were defeated in the decisive Battle of Mukden. That battle involved hundreds of thousands of soldiers on both sides and was one of the largest land engagements before World War I.[55]

Meanwhile, Russia had been forced to painstakingly redeploy its Baltic Sea fleet to the Pacific. Unfortunately for them, some of the Russian ships mistakenly fired on British fishing boats, nearly provoking the British into war and forcing most of the fleet to divert away from the Suez Canal.[56] As a result, the aging Russian fleet had to take an even longer sea route to get to Asia. Once the Russian fleet arrived, the Japanese welcomed them with the Battle of Tsushima, in which the modern Japanese fleet sank almost the entire Russian force while taking no significant losses.[57] That astounding Japanese victory forced the Russians to concede defeat, and they surrendered the southern half of Sakhalin island and their Chinese port to Japan.

Japan's defeat of a European imperial power confirmed its status as a force to be reckoned with.

Annexation of Korea[edit]

With Russia dealt with, Japan had a free hand to deal with Korea. Korea had been a target of Japanese expansionism for centuries, and after the Perry Expedition, Japan had started to emulate American-style gunboat diplomacy when dealing with it.[58] In 1905, the Japanese forced Korea into protectorate status. In 1907 Japan forced Korea to consult a Japanese general in all internal affairs,[59] and in 1910 this culminated in Korea's outright annexation.[60]

The Japanese treated the Koreans as second-class citizens from the annexation onwards despite theoretically granting them equal rights. Koreans could not publish their own newspapers or organize political or intellectual groups.[61] Harsh treatment by the Japanese eventually triggered anti-Japanese uprisings in 1919, which resulted in Japan treating the Koreans a bit nicer, at least until the Second World War. Nonetheless, the initial armed struggle against the Japanese came at a high cost, as nearly 17,700 Koreans were killed by the Japanese occupiers.[58]

Japan also significantly developed Korea's economy, but Koreans did not benefit from this. Virtually all industries were owned either by Japan-based corporations or Japanese corporations in Korea.[61] Korean entrepreneurs were charged interest rates 25 percent higher than their Japanese counterparts, so it was difficult for Korean enterprises to emerge. Japanese colonists also took over farmland from Koreans, meaning that the Koreans became little more than sharecroppers. Korea's rice cultivation was redirected to Japan, meaning that per capita consumption of rice among the Koreans declined; between 1932 and 1936, per capita consumption of rice declined to half the level consumed between 1912 and 1916.[61]

From the late 1930s until 1945, the colonial government instituted a policy of forced assimilation by attempting to require the Koreans to learn and speak Japanese, believe in the divinity of the emperor, and even take Japanese names.[61][58]

Japan in World War I[edit]

With Japan having been the British Empire's ally since 1902, it was inevitable that Japan would be sucked into the continental shitstorm that was World War I. After the British joined the war, the Japanese sent a diplomatic offer for themselves to enter the conflict and honor the alliance. In reality, the Japanese did this for self-serving reasons, as they hoped to use the war as an opportunity to annex the Pacific island colonies of the German Empire.[62] The British agreed that Japan should help out, and Japan declared war on Germany in August 1914.

Japan quickly focused its attacks on Germany's main outpost in China, the port of Qingdao (or "Tsing-tao", as the Germans called it, which lives on in the name of the beer). Its strategy in taking the area made the conquest quite easy. First, Japan blockaded Qingdao by land and sea, then it had its navy and artillery bombard the city, and finally, it attacked once the Germans had been sufficiently weakened.[63][64]

While Japan bullied Germany's forces in the Far East, it couldn't help but notice that this show of military power gave it a nice opportunity to push China around. In January 1915, Japan issued China the "21 Demands", ordering the Chinese government to recognize Japan's ownership of the former German concessions and granting Japan special economic privileges in China.[65] None of the Western powers could object since they were fighting alongside or against Japan, and Japanese forces were already dispersed throughout China to attack Germany's colonial outposts. China had no choice but to comply.

The Japanese navy also picked off the German island colonies in the Pacific while all of this was going on. Control of Pacific islands had long been a key objective for Japanese war planners. They had already identified the United States as their key rival for influence in the Pacific. These islands would prove to be useful naval outposts in a conflict.[63]

Turn to fascism[edit]

For about a decade after the First World War, Japan experienced a brief period called the "Taishō democracy", where there was a functioning two-party system.[66] Problems simmered beneath the surface of this seemingly quiet time. Socialist ideas became influential among the country's youth, and large but orderly protests happened daily for more electoral freedom and universal suffrage.[67] The old elites of Japan, though, were shocked and nervous about the victory of the communists in the Russian Civil War.

Although Japan was barely affected by the global Great Depression, its economy still had problems, and its political system became increasingly unstable. The government started to suppress leftists, causing them to become more radical. A series of harsh new election laws banned leftist parties, and strict enforcement pushed most leftist movements underground. In place of democracy, the Japanese elites focused on State Shintoism, exalting the emperor and championing a unique "Japanness" in the face of growing Western cultural influence.[68] This trend was only strengthened when Emperor Hirohito, known as Emperor Shōwa, came to the throne in 1927.

To consolidate Japan's turn to authoritarianism, the Japanese military inflicted a state of terror upon the people while attempting to distract them with promises of foreign expansionism. In 1931, the Japanese army staged a violent incident (the Mukden Incident![]() ) that served as an excuse for Japan to occupy Manchuria.[69] The military established the territory as the puppet state "Manchukuo", a move the civilian government had no influence over.[68]

) that served as an excuse for Japan to occupy Manchuria.[69] The military established the territory as the puppet state "Manchukuo", a move the civilian government had no influence over.[68]

Emboldened by these foreign successes, the Japanese military moved to overthrow the civilian government. In 1936, a cadre of military officers went on an assassination spree against the civilians, murdering many government members, including two former prime ministers.[70] Although the coup attempt failed, the civilian government resigned and allowed many high-level military officers to replace them. Japan had become a dictatorship, built on militarism and the promise of a great Japanese colonial empire.

Japan's new military regime aligned with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, eventually joining the Axis. Japan clashed with the Soviet Union over Mongolia and suffered a severe defeat, causing Japan to focus its expansionist aims on southern Asia. In 1940, the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of Japan, according to tradition, the military regime called for the establishment of a "Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere."[68] It was superficially anti-colonialist, but in reality, it would be Japan's planned Asian order as the head of a group of client states.

Second Sino-Japanese War[edit]

“”殺し尽くし・焼き尽くし・奪い尽くす. (koroshi tsukushi-yaki tsukushi-ubai tsukusu, Kill all, loot all, burn all).

|

| —Japanese scorched-earth policy in the war.[71] |

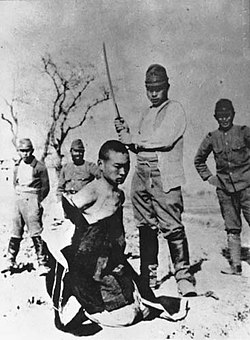

In 1937, Japan staged another border clash, the Marco Polo Bridge Incident,![]() and used it as a pretext to invade China. The Chinese nationalist forces, led by Chiang Kai-shek, were quickly overwhelmed by Japan's superior technology and tactical training. Japanese forces moved quickly along the Chinese coastline, seizing China's capital of Nanjing within months.[72]

and used it as a pretext to invade China. The Chinese nationalist forces, led by Chiang Kai-shek, were quickly overwhelmed by Japan's superior technology and tactical training. Japanese forces moved quickly along the Chinese coastline, seizing China's capital of Nanjing within months.[72]

The capture of Nanjing provided the first great demonstration of Japanese brutality. In the Rape of Nanjing, an orgy of murder and rape transpired that resulted in as many as 300,000 deaths.[73] It was so bad that a local Nazi, John Rabe,![]() was compelled to help shelter people.

was compelled to help shelter people.

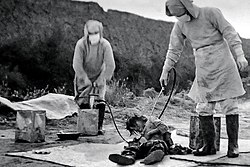

Then Japan started using the weapons of Unit 731, a biowarfare team that had stockpiled bubonic plague, anthrax, and cholera. In 1935, it tested its weapons by dropping aerial bombs filled with sawdust and plague-infected fleas over Manchurian population centers in an attack that killed as many as 600,000 people.[73] The unit also conducted human experimentation against civilians and POWs, vivisecting people and testing weapons like flamethrowers on live human beings. Japan also forced hundreds of thousands of civilian women from its occupied territories into sexual slavery, calling them comfort women.

Beyond 1938, the war reached a virtual stalemate. China's geographical size, lack of infrastructure, and scattered pockets of resistance helped slow the Japanese advance.[72] Japanese atrocities in China, though, caused the US to view them with disgust. Relations only got worse when the Japanese "accidentally" bombed the USS Panay, which had been evacuating US civilians from China.[74] The US retaliated in 1940 by loaning military aid to China and then slapping an embargo on all militarily useful materials to Japan.[74] The immediate main effect of the embargo was to cut off Japan's access to fuel oil, particularly the type used to power ships ("bunker oil").[75] Cut off from natural resources, Japan had only bad choices. It could end the war in China, thus getting the US to lift the embargo. Or, it could attack the US and its allies to conquer resource-rich land in south Asia.

Japan in World War II[edit]

Opening offensives[edit]

“”In the first six to twelve months of a war with the United States and Great Britain I will run wild and win victory upon victory. But then, if the war continues after that, I have no expectation of success.

|

| —Marshal Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku's assessment of the Japanese government's war plans.[76] He was proven right six months later |

As just about everyone knows, Japan decided to bomb Pearl Harbor to take the US Pacific Fleet out of action and allow it to swiftly take over Asia with no opposition. Dutch and Commonwealth forces were occupied elsewhere during the war against Adolf Hitler and could not put up much more than token resistance when the Japanese attacked their colonies. Japan started with an air attack and invasion of British Malaya.[77] Japan then occupied Thailand and turned it into a puppet state, aiming to use its border with British India as a springboard for an invasion.[78] Japan then took Hong Kong, Singapore, and Indonesia and began its invasion of British-held Burma. Singapore saw another horrific Japanese massacre, as Japan murdered about 70,000 prisoners and ethnic Chinese.[79]

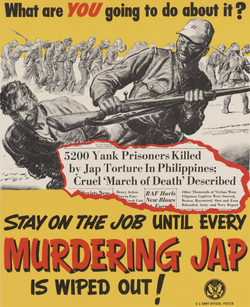

Japan also hit the Americans again right after Pearl Harbor, managing to catch US planes on the ground and unready in the Philippines due to General MacArthur's inaction and incompetence.[80] The Japanese conquered the Philippines despite fierce American and Filipino resistance before murdering thousands of POWs during the Bataan Death March.[81]

Turning point and island hopping[edit]

“”The Three Great Allies expressed their resolve to bring unrelenting pressure against their brutal enemies by sea, land, and air... The Three Great Allies are fighting this war to restrain and punish the aggression of Japan... It is their purpose that Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the first World War in 1914, and that all the territories Japan has stolen from the Chinese, such as Manchuria, Formosa, and The Pescadores, shall be restored to the Republic of China.

|

| —The Cairo Declaration by the US, UK, and China.[82] |

By 1942, though, the Allies were starting to regroup. In revenge for Pearl Harbor, the US launched the Doolittle Raid, a bombing run against the Japanese mainland. The US troopers were forced to bail in China, where they were sheltered by the Chinese, and Japan retaliated against the Chinese with a horrific massacre of 10,000 people.[79] Unit 731 also handed out typhoid-infected bread rolls to starving Chinese prisoners and then set them loose to spread the disease.

In the face of increasing American naval power, Japan hoped to draw in the US fleet for a decisive engagement that would crush the US navy![]() and open the door for a negotiated settlement on favorable terms for Japan.[83] That decisive engagement was the Battle of Midway

and open the door for a negotiated settlement on favorable terms for Japan.[83] That decisive engagement was the Battle of Midway![]() , where the US destroyed most of Japan's aircraft carrier forces and decisively turned the war in its favor. That began a long, hard string of Japanese naval defeats, but the Japanese army on the ground still fought diligently whenever the Allies faced them.

, where the US destroyed most of Japan's aircraft carrier forces and decisively turned the war in its favor. That began a long, hard string of Japanese naval defeats, but the Japanese army on the ground still fought diligently whenever the Allies faced them.

The Allies adopted the "island hopping" strategy, hoping to take islands closer and closer to Japan to mount an invasion of the Home Islands. This started in Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands, a ferocious struggle marked by seven major naval battles, three major land battles, and almost continuous air combat.[84] General MacArthur's southern offensive continued while a separate US operation went further north to target Tarawa at the Gilbert Islands. The vital part of the strategy was that the US didn't have to take every Japanese-held island; US naval power could cut un-conquered islands off and make them basically irrelevant.[85]

By 1944, most of the Pacific was under US control and at the end of that year after several![]() massive

massive![]() naval battles, the Imperial Japanese Navy was seriously crippled and caused Japan to start resorting to kamikaze suicide strikes, hoping to shock the Americans even if that failed to turn the war, but the Japanese army was holed up in the Home Islands with most of its strength intact.

naval battles, the Imperial Japanese Navy was seriously crippled and caused Japan to start resorting to kamikaze suicide strikes, hoping to shock the Americans even if that failed to turn the war, but the Japanese army was holed up in the Home Islands with most of its strength intact.

Preparing to invade Japan[edit]

The final months of the Pacific campaign were focused on preparing for an all-out invasion of the Japanese Home Islands. Japan was cut off from most of its forces and resources abroad, and US submarines sank most Japanese ships brave enough to try anything. Despite this disaster, though, the Japanese did try one last huge offensive in late 1944 in China, which inflicted huge damage on the nationalist forces.[86] However, it didn't improve the empire's war against the Western Allies.

In early 1945, the US invaded Iwo Jima in the Bonin Islands south of Japan. The month-long battle was a hell on earth for all sides, as the Japanese used the previous lessons of war to fight a well-fought but doomed battle of resistance against the overwhelming American strength. Iwo Jima was the only battle in the Pacific where the US Marines suffered more casualties than they inflicted.[87]

In mid-1945, the US turned its sights to the last island on the path to Japan: Okinawa. This would be the bloodiest US battle of the Pacific War, as the Japanese launched their largest spree of suicide attacks by sea, including the sacrifice of the last

operational ships of their navy![]() , and put up a determined defense on land. Among the Americans killed was Army Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., the highest-ranking US KIA in its history.[88]

, and put up a determined defense on land. Among the Americans killed was Army Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr., the highest-ranking US KIA in its history.[88]

Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki[edit]

The Borneo Campaign in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia) proved to be the last major Allied campaign of the war, and it was a bloody mess.[89] Conventional bombing raids over Japanese cities killed countless people. One firebombing raid leveled Tokyo itself.

The Allies also started preparing the Operation Downfall plan, which was the proposed invasion of the Japanese Home Islands and could potentially have cost millions of Allied and Japanese lives.[90] That grim prospect was averted when US President Harry Truman found out about the US nuclear weapons program and ordered the atomic bombing of two Japanese cities.

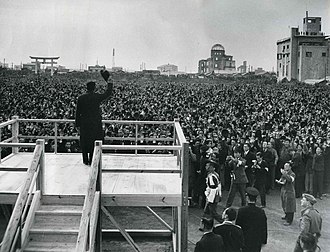

The first bomb fell on Hiroshima, killing around 70,000 people instantly and doubling that death toll over time due to radioactive fallout.[91] The heat and pressure vaporized many people and destroyed most of the city; many more died due to health complications. The US targeted Hiroshima because it had thus far been spared from conventional bombing raids and was considered a significant military base.[92]

When Japan failed to respond to the first nuclear bombing, the US hit Nagasaki. Although the Hiroshima strike had been planned, Nagasaki was hastily chosen (they originally wanted to bomb Kokura, but cloud conditions that day made it impossible) and had already been bombed and partially evacuated.[93] That's why the death toll was so much smaller.

Combined with the Soviet Union's breaking of their truce with Japan and subsequent invasion of Manchuria, the endgame catastrophes forced Japan's Emperor Hirohito finally to agree to surrender to the Allies. The terms of surrender included the occupation of Japan by Allied military forces, assurances that Japan would never again go to war, restriction of Japanese sovereignty to its Home Islands, and surrender of all of Japan's colonies.[94]

Military occupation and reconstruction[edit]

“”Unite your total strength, to be devoted to construction for the future. Cultivate the ways of rectitude, foster nobility of spirit, and work with resolution – so that you may enhance the innate glory of the imperial state and keep pace with the progress of the world.

|

| —Emperor Hirohito's final message to the Japanese people in his broadcast of surrender.[95] |

So, Japan spent about eight years committing horrific war crimes and then getting its shit pushed in. You don't come back from that without a little bit of work. Immediately after Japan's surrender, the country fell under Allied military occupation. Although theoretically an international effort, the primary burden of the occupation fell upon the United States military under the command of General Douglas MacArthur.[96]

MacArthur immediately had all military factories torn down and set about helping the Japanese create a new constitution. The new constitution confirmed that Japan would be a sovereign democracy with its legislature (the National Diet) replacing the emperor as the supreme legal authority in Japan.[97] The constitution also guaranteed certain civil liberties like women's equality and freedom of speech.

MacArthur and the United States also held the Tokyo War Crimes Trials, Japan's version of the Nuremberg Trials. To be clear, those Asian countries that Japan had more directly victimized got to deal with most Japanese war criminals, executing hundreds and sentencing many more to life sentences in prison.[98]

However, the US was in charge of occupying Japan itself and thus got the prestigious responsibility of placing Japan's highest authorities on trial. The Tokyo Trials began in 1946, and it has been heavily criticized as "victor's justice" since its relationship with established international law was admittedly shaky.[98] The court convicted all defenders and had many of them hanged, including many of Japan's top generals and its defeated prime minister Tojo Hideki. Notably absent from the defendant's dock? Emperor Hirohito was spared from any liability by the Americans since they didn't want to infuriate the Japanese people.[99]

Millions of Japanese colonists, spread out all over Asia, were compelled to return to the Home Islands. The hikiagesha, or "repatriates", had grown culturally distinct from their Home Islands' counterparts and faced discrimination.[100]

To support the many political changes in Japan, the Americans enforced many economic and even cultural adaptations. First, the Americans instituted broad land reform, redistributing land from large absentee landholders and handing it out to farmers.[97] Because farm families became more independent economically, they could participate more freely in the new democracy. However, the Americans did not try to break up Japan's huge state-run zaibatsu corporations, as they figured this might have made economic recovery much more difficult.

The most successful aspect of democratization was the Americans' usage of Japanese media outlets to publish pro-democracy propaganda. Combined with educational reforms, this policy helped inspire broad public support for Japan's new direction as a country. After the American withdrawal in 1952, most of the reforms were kept despite some bickering in the Diet.[97]

All was not sunshine and roses, though. Rape and sexual violence inflicted on Japanese women by American servicemen was so common that the Japanese authorities established the "Recreation and Amusement Association" to organize state-run prostitution catering to occupying soldiers.[101] Working conditions in these brothels were about as bad as you'd expect, mainly since the Americans were operating from a position of power over a defeated enemy culture. Despite ample warning, the Americans did nothing about Yoshio Kodama![]() , who had long been a hugely powerful figure in the Japanese underworld; thanks to letting him run free, the yakuza flourished to a degree even the Mafia could only dream of, and despite being a band of organized criminals they remain strangely well-integrated in mainstream Japanese society.

, who had long been a hugely powerful figure in the Japanese underworld; thanks to letting him run free, the yakuza flourished to a degree even the Mafia could only dream of, and despite being a band of organized criminals they remain strangely well-integrated in mainstream Japanese society.

Economic "miracle"[edit]

Japan's first postwar leader, Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida, set Japan's strategy going into the future. The so-called Yoshida Doctrine stated that the Japanese government would abandon its pre-war imperialism to focus on economic growth and depend on its security relationship with the United States.[102] However, much of that was forced since Article 9 of the new constitution clarified that Japan could never return to its warlike ways again. Yoshida's party later became the right-wing Liberal Democratic Party, continuously in power since 1955.[103]

Japan's economic boom era began during the Korean War. It became the primary staging area for the United Nations coalition and thus provided many necessary supplies for the war effort.[104] Farmers had benefited greatly from the American land reform, allowing them to mechanize agriculture to produce greater yields and profits and thus increase Japan's overall wealth.[104] That led to the development of a consumer economy that fueled further industrialization. Japan's rapid turnaround from the postwar ruination led to the term "economic miracle".

Between 1967 and 1971 saw Japan's most rapid period of growth by far, but its economy still managed to keep things going during the OPEC oil crisis of 1973.[105] A big contributor to this was Japan's powerful tech industry, most famously including Japan's enthusiastic embracement of the video games industry. Japanese video game titans like Nintendo and Sega drove the early enthusiasm for video games and helped create the electronics market as the world knows it today.[106] Japan also had multiple automobile and electronics titans like Toyota, Honda, and Mitsubishi.

Japan's economic growth got so powerful that it started causing severe tensions with the United States. The US economy, especially the manufacturing industry, stagnated in the early 1980s while Japan made a killing selling cars, semiconductors, and consumer electronics.[107] Trade with Japan became a focus of the Ronald Reagan administration, which pressured Japan into limiting its automobile exports and started imposing tariffs on Japanese electronics. Japan had no choice but to accept these economic bitch-slaps since it depended on the US for defense. Things were about to change for Japan for the worse.

Stagnation and modern Japan[edit]

Trouble started brewing in the mid-1980s, as its economy took on billions of dollars of bad corporate debt.[108] It also became clear that Japan's success was at least partially based on the fact that it had an industrialization model to follow. Once it was caught up, the path forward became much less clear. The seeds of trouble Japan had sown during its climb to the top started sprouting. Many of Japan's proposed technological innovations started failing to send returns. Japan's rigid and bureaucratic workplace culture prevented it from catching up to the US' head start on the internet.[108] Many Japanese were also encouraged to postpone having a family to get higher education. Japanese youth increasingly decided that it wasn't in their economic interest to have children.[109] As a result, Japan's population growth fell and then went negative.

These factors combined around 1991 to bring Japan's economy to a screeching halt. During the so-called "Lost Decade", Japan's economy lagged way behind the rest of the industrial world.[110] Although the Lost Decade is technically over, policymakers still are concerned about Japan's economy. Shinzō Abe took office on the promise to use his "Abenomics" policy to unfuck Japan's economy. His rule was a mixed economic bag, though, as unemployment went down but wages are still stagnant, and Japan's aging population still presents a severe problem in the near future.[111]

Government and politics[edit]

Yamato monarchy (or how to win by doing nothing)[edit]

The Yamato dynasty is currently the ruling house of Japan, and it's lasted more than a millennium, making it one of the longest-lived royal families in the world. Its origin story from the very beginning was deliberately shrouded in religious myth to portray the emperor as a divine being. While many Western rulers claimed divine authority, the Japanese emperors simply portrayed themselves as a divine and integral aspect of Japanese culture.[112] Indeed, the real secret behind the imperial dynasty's longevity was its ability to adapt to changing political circumstances. Because the dynasty claimed divine nature rather than divine authority, the emperors could easily fade into the background and let other people run things in their name.[112] As a result, it was never necessary for any potential usurpers to view the imperial dynasty as a threat. It was instead far more useful to maintain them as quasi-religious symbols. Therefore, while Imperial China saw dynasties rise and fall, Japan has had one dynasty on its throne basically forever.

That pattern, where emperors are revered as a figurehead rather than a leader, has persisted into the modern day. After Japan lost World War II, the US overhauled its imperial system and reduced the emperor to "the symbol of the State and of the unity of the People."[113] In other words, the emperor was relegated back to the same role he had fulfilled during the Fujiwara and Shogunate eras. The much-touted surrendering of the imperial divinity really didn't impact the monarchy. The emperor was considered divine in that he was related to Shinto spirits; he was not considered infallible or a literal god.[114] Thus, surrendering the emperor's authority as a god was almost redundant since he was a symbol of the nation rather than a manifest deity.

Of course, some aspects of tradition still stuck to the emperor's role. Women, for instance, may not ever ascend the Chrysanthemum Throne, and the emperor's wife must always deferentially remain a few steps behind him.[115]

Conservative one-party state[edit]

It's no secret that Japanese forces conducted extensive looting of occupied territories during its imperial period. However, the historical analysis in The Yamato Dynasty: The Secret History of Japan's Imperial Family by Sterling and Peggy Seagrave suggests that much of this wealth, which went missing after the war, financed the Liberal Democratic Party.[116]

The Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) has dominated Japanese politics since its formation in 1955. All of Japan's prime ministers and most of its high-level government officials until 1993 came from this party.[117] The party doesn't really have a solid ideology. Instead, it simply supports whatever policies happen to be in the interest of big businesses at any given moment. Japan's latest two nationalist leaders, Shinzō Abe and Yoshihide Suga, came from this party. The LDP gets away with its various shenanigans (see below) because there isn't any viable opposition party. Abe and his party routinely get disapproval ratings over 40%, but the opposition Democratic Party is basically defunct due to internal divisions and power plays.[118]

As a result of Japan's being an effectively one-party state, the LDP can be guaranteed to win elections easily despite backing controversial and dangerous policies like tax hikes, an end to pacifism, and raiding the pension system.[119]

Return to the old ways[edit]

_06.jpg/330px-Shinzō_Abe_visits_Russia_(2018-05-26)_06.jpg)

The Liberal Democratic Party and its most influential leader Shinzō Abe were dead set on returning Japan to its authoritarian and militaristic past. Abe has been described as the "Donald Trump before Donald Trump". He ran on a platform calling to "Take Back Japan". His stint as prime minister was focused on removing Japan from its postwar limitations, rewriting history about Japan's war crimes, and standing firm on territorial disputes with Japan's neighbors.[120] In 2015, he effectively bypassed Japan's constitutional prohibition on war by radically reinterpreting it in legislation he rammed through the Diet, meaning that Japan now claims the right to declare war at will.[121]

Abe and his party also weakened Japan's democratic institutions. In 2015 and 2017, Mr. Abe ignored calls by opposition members of the Diet to convene sessions to discuss controversial legislation, which is a right Article 53 of Japan's constitution guarantees.[118] The prime minister also frequently dissolves the parliament whenever he feels like it, and he uses that power to suppress dissent and ram through bad legislation.

Shitty legislation rammed through by Abe's government included a state secrets law that authorizes the government to hide politically inconvenient truths and jail journalists[122] and an "anti-conspiracy" law that gives the government broad surveillance powers against "suspected criminals."[123] Press freedom? Dropped dramatically since 2012 due to Abe's tactic of marshaling market forces and online nationalist groups to hound independent journalists and harass uncooperative publications.[124] The government says these measures stop crime, but crime in Japan has hit a record low, and the last terrorist attack was more than 20 years ago.[125]

LDP members routinely tout their contempt and disgust toward democratic norms and rights. Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Taro Aso notoriously cited Nazi Germany as a good role model for revising the pacifist Constitution.[126] When Japanese citizens peacefully protested against the state secrets law, Liberal Democratic Party Secretary-General Shigeru Ishiba said they were committing "acts of terrorism."[127] Mio Sugita, an LDP member of the Diet, said in 2018 that same-sex couples "don’t produce children. In other words, they lack productivity and, therefore, do not contribute to the prosperity of the nation."[128] The LDP signaled its support for these comments by refusing to condemn her.

Most worrying of all is the authoritarian transformation of Japan's schools. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe wanted to revive the spirit of the Imperial Rescript on Education, issued in 1890, that encourages children to "offer yourselves courageously to the State".[129] Other disturbing trends are the rise of "black" clubs that subject students to harsh treatment and physical punishments, growing class sizes, suppression of individuality, and a mandate that schools instill patriotism in children.[129]

Ultranationalism and the far-right[edit]

Like many other countries, Japan has seen the rise of nationalist movements in previous years. That has been driven by separate factors from the West's rightward turn. Abe encouraged a conspiracy theory during his first term claiming that North Korean spies had kidnapped some random couple's 13-year-old daughter and hustled her onto a submarine.[130] He used that conspiracy theory and genuinely true stories of North Korean misdeeds to stoke fears in the country and encouraged support for his tough stance towards Japan's neighbors. Japan's fear of North Korea and an increasingly aggressive China have fueled Abe's push to end Japanese pacifism and erode democracy.

Japan, in general, has become more nationalistic and more conservative, to the point where Western alt-right figures like Steve Bannon, German Alternative für Deutschland member Jan Moldenhauer, and Italian neo-fascist Simone di Stefano all openly see Japan as an example and potential ally.[131] The Japanese far-right has successfully found a home within the establishment of LDP. Prime Minister Abe was a special advisor for Nippon Kaigi, a radical nationalist group that wants to return Japan to its imperial days.[131] Japan also sees attacks on the media by the LDP, harsh restrictions on immigration, and abuse directed towards racial minorities.

Nippon Kaigi, the country's largest, most powerful conservative group, openly derides Japan's constitution and hates "liberal" values.[132] The group and Japan's far-right movement have roots in the immediate postwar opposition to Japan's new democracy. Although antiwar sentiment was too strong initially, the far-right found other rallying cries like anti-feminism in the 1990s, anti-communism still to this day, and an ongoing push to restore patriotism by scrubbing Japanese war crimes from textbooks.[132]

At least 900 uyoku dantai, or far-right groups, regularly protest in front of foreign embassies and harass Korean and Chinese ethnic communities.[133]

Rise of Sanseitō[edit]

Founded in 2020 by a man named Sohei Kamiya, Sanseitō is a far-right, ultranationalist party whose leader (Kamiya) won a seat in parliament after complaining about "Jewish capital."[134] Once seen as a fringe group, Sanseitō only had Kamiya as their lone member of parliament. But Kamiya used that time as the face and core of his party to elevate his preferred policies and build an army of followers using social media. How did he accomplish this? Sanseitō's motto is "Japanese First," claiming that foreigners bring crime and receive better treatment than native citizens. In fact Kamiya openly says immigration is a "silent invasion of foreigners."[135] Sanseitō also promotes COVID vaccine misinformation, with one of their party leaders, Manabu Matsuda calling the vaccine a "murder weapon." And on top of that, Sanseitō unironically thinks anime and manga are too degenerate, so if they take power, they plan to regulate anime and manga to ensure they only promote stories which champion "healthy development" for Japanese culture. [136] What kind of "cultural values" do they want to promote in Japan? We can tell which ones they don't want - Sanseitō hates gay marriage, opposes LGBT rights in general, and proposes drafting a new constitution that doesn't respect human rights. [137] Why are they so important? Because after three years of having only Kamiya as an MP, on a platform explicitly calling for cultural censorship in anime and manga, curtailing gender equality efforts, reversing diversity initiatives, striking down LGBT rights, deemphasizing human rights, and phasing out immigration, Sanseitō won three new MPs in the lower chamber and fourteen new MPs in Japan's upper chamber in 2025. Now everyone's forced to finally pay attention to their nonsense. Much of their support comes from Kamiya's grassroots effort, speaking to citizens directly via social media and getting his supporters elected to local council seats. [138]

"Abenomics"[edit]

Of course, much of this nationalist bullshittery is designed to distract from Japan's real problem: the economy. After Abe's failed first run as prime minister back in 2006, he came back to the saddle with promises of huge "Abenomics" reforms that would return Japan's economy to the days of booming growth. That hasn't materialized. Instead, Abe waits for marginally good news, like Sony making money or inflation ticking up by a tenth of a percent. He trumpets it as his own personal success while hoping people don't notice how he's whittling away at democratic institutions.[139]

If you look at the facts, Abenomics has proven nothing short of absolute failure. The idea was textbook Ronald Reagan: deregulation combined with fiscal stimulus and monetary easing. Its positive effect on the economy was negligible, and the negative effect was huge. The economy jolted a bit and then slumped back over like an electrocuted corpse, and Japan's national debt skyrocketed to 250% of GDP.[140] Japan was once known for high levels of lifetime employment. Now, Abe's deregulation of the labor industry has resulted in a market where 40% of the labor force now works on temporary contracts.[140] With job security gone, things like pensions, unemployment insurance, and healthcare coverage are gone. That has had the effect you might expect on Japan's population growth. Why have a kid when you can't possibly hope to pay for it?

Culture[edit]

Suicide[edit]

“”The fastest growing suicide demographic is young men. It is now the single biggest killer of men in Japan aged 20-44. And the evidence suggests these young people are killing themselves because they have lost hope and are incapable of seeking help. The numbers first began to rise after the Asian financial crisis in 1998. They climbed again after the 2008 worldwide financial crisis. Experts think those rises are directly linked to the increase in "precarious employment", the practice of employing young people on short-term contracts. Japan was once known as the land of lifetime employment. But while many older people still enjoy job security and generous benefits, nearly 40% of young people in Japan are unable to find stable jobs.

|

| —Rupert Wingfield-Hayes, BBC News, July 2015.[141] |

The Aokigahara forest near Mount Fuji is infamous as the "Suicide Forest" since roughly a hundred or so people attempt suicide there each year.[142] Suicide has been considered a severe social issue here for decades, and it's quite likely tied to the fact that Japan's economy is in the shitter and future prospects for young people are dim and getting dimmer.[143]

The problem is that Japanese culture has historically viewed suicide as a noble act. Suicide was considered a way to go out honorably, and in a culture where unemployment is considered shameful, suicide becomes an obvious course of action.[144] As unemployment and high personal debts rise, so too does the social stigma, feeling of helplessness, and the perceived need to find the best way out. Even today, suicide is considered a morally responsible action for someone who has "failed" their family and themselves.[145]

Also worrying is the rising trend of online Shinjū pacts, where online Japanese communities would crop up revolving around suicide to encourage and enable group suicide pacts.[146]

There are signs of progress, though. 2019 marked the tenth consecutive year that suicide numbers have declined, and the Japanese government is still focusing on efforts to keep bringing that number down.[147] The fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic also brought the issue of suicide to the forefront of Japanese consciousness, as the single month of October 2020 saw more suicide deaths than Japan had COVID deaths in that entire year.[148] Despite Japan seeing a relatively light impact from the virus. By 2021, the suicide issue had gotten so bad that the recently-elected Japanese prime minister Yoshihide Suga appointed an actual "Minister of Loneliness" to address Japan's social isolation and suicide crises.[149]

Whaling[edit]

“”Admiral, if we were to assume these whales were ours to do with as we pleased, we would be as guilty as those who caused their extinction.

|

| —Mr. Spock, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home.[150] |

Recently, whaling has been criticized within Japan, perhaps reflecting changing dietary trends — few people eat whale meat nowadays. Whaling is still supported in rural communities across Japan, though only a handful still depend on it for their livelihoods. Only a few whaling vessels are still active, under heavy subsidies due to its lack of profitability, and whaling has been declining even if the government's supposed target numbers haven't.[151]

There have been several incidents during which Japanese whaling ships have come under attack from hard green environmental groups such as the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society.[152] Such attacks ironically reduce the Japanese government's desire to stop whaling since it'd be a severe loss of face to appear to give in to foreign pressure. It's also hard to convince people that their culture is wrong and yours is morally superior by throwing shitty-smelling substances (butyric acid) at them.[153]

In contrast, the general public is pretty apathetic about the whole thing. Almost all young people, especially women, don't eat whale meat. Not much of the older generations eat it regularly either. However, most Japanese of all ages believe cultures should be allowed to hunt whales if it is a traditional activity and they want to. Still, few have strong opinions about whether Japanese whaling should or shouldn't continue.[154]