Life (Magazine)

From Nwe

From Nwe Life is an American magazine that publishes interviews, essays, cartoons, and photographs. Since 1972, Life has ceased publication twice, only to be brought back to readers in different incarnations. Today, Life is distributed as a free supplement in major U.S. newspapers. The first incarnation of Life was as a humor magazine in the 1880s. It later took the form of a photojournalism magazine under Henry Luce, and then as a monthly magazine, before reaching its current weekly supplement format. At one point it sold more than 13.5 million copies a week. In the years following World War II, Life was so popular that President Harry S. Truman, Sir Winston Churchill, and General Douglas MacArthur all serialized their memoirs in its pages. Although no longer fulfilling such an influential role, Life impacted society in unforgettable ways, bringing events and personalities in the world home to all through its images and "photo essays," allowing people to come closer together and thus advancing humankind as one family.

History

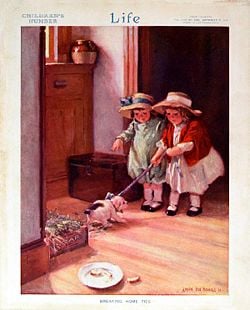

Founding (1883 - 1936)

Life was founded January 4, 1883, in a New York City artist’s studio at 1155 Broadway. The founding publisher was John Ames Mitchell, a 37-year old illustrator, who used a $10,000 inheritance to launch the weekly magazine. Mitchell created the first Life nameplate with cupids as mascots; he later drew its masthead of a knight leveling his lance at a fleeing devil. Mitchell took advantage of a revolutionary new printing process using zinc-coated plates, which improved the reproduction of his illustrations and artwork. This helped because Life faced stiff competition from the bestselling humor magazines The Judge and Puck, which were already established and successful. Edward Sandford Martin, a Harvard graduate and a founder of the Harvard Lampoon, was brought on as Life’s first literary editor.

The motto of the first issue of Life was “While there’s Life, there’s hope.” The new magazine set forth its principles and policies to its readers:

We wish to have some fun in this paper... We shall try to domesticate as much as possible of the casual cheerfulness that is drifting about in an unfriendly world... We shall have something to say about religion, about politics, fashion, society, literature, the stage, the stock exchange, and the police station, and we will speak out what is in our mind as fairly, as truthfully, and as decently as we know how.[1]

The magazine was a success and soon attracted the industry’s leading contributors. Among the most important was Charles Dana Gibson. Three years after the magazine was founded, the Massachusetts native sold Life his first contribution for $4: a dog outside his kennel howling at the moon. Encouraged by a publisher who was also an artist, Gibson was joined in Life’s early days by such well-known illustrators as Palmer Cox, A. B. Frost, Oliver Herford, and E. W. Kemble. Life attracted an impressive literary roster too: John Kendrick Bangs, James Whitcomb Riley, and Brander Matthews all wrote for the magazine at the beginning of the twentieth century.

However, Life also had its dark side. Mitchell was sometimes accused of outright anti-Semitism. When the magazine blamed the theatrical team of Klaw and Erlanger for Chicago’s grisly Iroquois Theater Fire in 1903, a national uproar ensued.

Life became a place that discovered new talent; this was particularly true among illustrators. In 1908 Robert LeRoy Ripley published his first cartoon in Life, 20 years before his Believe It or Not! fame. Norman Rockwell’s first cover for Life, "Tain’t You," was published May 10, 1917. Rockwell’s paintings were featured on Life’s cover 28 times between 1917 and 1924. Rea Irvin, the first art director of The New Yorker and creator of Eustace Tilley, got his start drawing covers for Life.

Just as pictures would later become Life’s most compelling feature, Charles Dana Gibson dreamed up its most celebrated figure. His creation, the "Gibson Girl," was a tall, regal beauty. After her early Life appearances in the 1890s, the Gibson Girl became the nation’s feminine ideal. The Gibson Girl was a publishing sensation and earned a place in fashion history.

This version of Life took sides in politics and international affairs, and published fiery pro-American editorials. Mitchell and Gibson were incensed when Germany attacked Belgium; in 1914 they undertook a campaign to push America into the war. Mitchell’s seven years spent at Paris art schools made him partial to the French. Gibson drew the Kaiser as a bloody madman, insulting Uncle Sam, sneering at crippled soldiers, and even shooting Red Cross nurses. Mitchell lived just long enough to see Life’s crusade result in the U. S. declaration of war in 1917.

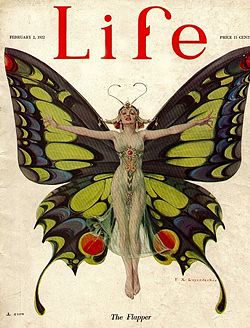

Following Mitchell’s death in 1918, Gibson bought the magazine for $1 million. But the world was a different place for Gibson’s publication. It was not the "Gay Nineties" where family-style humor prevailed and the chaste Gibson Girls wore floor-length dresses. World War I had spurred changing tastes among the magazine-reading public. Life’s brand of fun, clean, cultivated, humor began to pale before the new variety: crude, sexy, and cynical. Life struggled to compete on newsstands with such risqué rivals.

In 1920, Gibson tapped former Vanity Fair staffer Robert E. Sherwood to be editor. A World War I veteran and member of the Algonquin Round Table, Sherwood tried to inject sophisticated humor onto the pages. Life published Ivy League jokes, cartoons, Flapper sayings, and all-burlesque issues. Beginning in 1920 Life undertook a crusade against Prohibition. It also tapped the humorous writings of Frank Sullivan, Robert Benchley, Dorothy Parker, Franklin P. Adams, and Corey Ford. Among the illustrators and cartoonists were Ralph Barton, Percy Crosby, Don Herold, Ellison Hoover, H. T. Webster, Art Young, and John Held Jr..

Despite such all-star talents on staff, Life had passed its prime, and was sliding toward financial ruin. The New Yorker, debuting in February 1925, copied many of the features and styles of Life; it even raided its editorial and art departments. Another blow to Life’s circulation came from raunchy humor periodicals such as Ballyhoo and Hooey, which ran what can be termed outhouse gags. Esquire joined Life’s competitors in 1933. A little more than three years after purchasing Life, Gibson quit and turned the decaying property over to publisher Clair Maxwell and treasurer Henry Richter. Gibson retired to Maine to paint and lost active interest in the magazine, which he left deeply in the red.

Life had 250,000 readers in 1920. But as the Jazz Age rolled into the Great Depression, the magazine lost money and subscribers. By the time Maxwell and editor George Eggleston took over, Life had switched from publishing weekly to monthly. The two men went to work revamping its editorial style to meet the times, and in the process it did win new readers. Life struggled to make a profit in the 1930s when Henry Luce pursued purchasing it.

Announcing the death of Life, Maxwell declared: “We cannot claim, like Mr. Gene Tunney, that we resigned our championship undefeated in our prime. But at least we hope to retire gracefully from a world still friendly.”

For Life’s final issue in its original format, 80-year-old Edward Sandford Martin was recalled from editorial retirement to compose its obituary:

That Life should be passing into the hands of new owners and directors is of the liveliest interest to the sole survivor of the little group that saw it born in January 1883. ... As for me, I wish it all good fortune; grace, mercy and peace and usefulness to a distracted world that does not know which way to turn nor what will happen to it next. A wonderful time for a new voice to make a noise that needs to be heard! [1]

The photojournalism magazine (1936 - 1960)

In 1936 publisher Henry Luce paid $92,000 to the owners of Life magazine because he sought the name for Time, Inc. Wanting only the old Life’s name in the sale, Time Inc. sold Life’s subscription list, features, and goodwill to The Judge.

Convinced that pictures could tell a story instead of just illustrating text, Luce launched his version of Life on November 23, 1936. The third magazine published by Luce, after Time in 1923 and Fortune in 1930, Life gave birth to the photo magazine in the U.S., giving as much space and importance to pictures as to words. The first issue of Life, which sold for 10 cents, featured five pages of Alfred Eisenstaedt’s pictures.

When the first issue of Life magazine appeared on the newsstands, the U.S. was in the midst of the Great Depression and the world was headed toward war. Adolf Hitler was firmly in power in Germany. In Spain, General Francisco Franco’s rebel army was at the gates of Madrid; German Luftwaffe pilots and bomber crews, calling themselves the Condor Legion, were honing their skills as Franco’s air arm. Italy’s Benito Mussolini annexed Ethiopia. Luce ignored tense world affairs when the new Life was unveiled: the first issue depicted the Fort Peck Dam in Montana photographed by Margaret Bourke-White.

The format of Life in 1936 was an instant classic: the text was condensed into captions for fifty pages of pictures. The magazine was printed on heavily coated paper that cost readers only a dime. The magazine’s circulation skyrocketed beyond the company’s predictions, going from 380,000 copies of the first issue to more than one million a week four months later.[2] It spawned many imitators, such as Look, which folded in 1971.

Luce pulled Time's Edward K. Thompson, to become assistant picture editor in 1937. From 1949 to 1961 he was the managing editor, and served as editor-in-chief until his retirement in 1970. His influence was significant during the magazine’s heyday—roughly from 1936 until the mid-1960s. Thompson was known for the free reign he gave his editors, particularly a “trio of formidable and colorful women: Sally Kirkland, fashion editor; Mary Letherbee, movie editor; and Mary Hamman, modern living editor.”[3]

Life moved its headquarters to 9 Rockefeller Plaza in 1937, from its original building, a Beaux-Arts architecture jewel built in 1894 and considered of "outstanding significance" by the New York Landmarks Preservation Commission at 19 West 31st Street.

The magazine became archly conservative, and attacked organized labor and trade unions. In August 1942, writing of labor unrest, Life concluded: “The morale situation is perhaps the worst in the U.S. It is time for the rest of the country to sit up and take notice. For Detroit can either blow up Hitler or it can blow up the U.S.” Detroit’s Mayor Edward J. Jeffries was outraged: “I’ll match Detroit’s patriotism against any other city’s in the country. The whole story in Life is scurrilous. I’d just call it a yellow magazine and let it go at that.”[4] Martin R. Bradley, a U.S. Collector of Customs, was ordered to tear out of the August 17 issue five pages containing an article captioned “Detroit is Dynamite” before permitting copies of the magazine to cross the international border to Canada.

When the U.S. entered the war in 1941, so did Life. By 1944 not all of Time and Life’s 40 war correspondents were men; six were newswomen: Mary Welsh, Margaret Bourke-White, Lael Tucker, Peggy Durdin, Shelley Smith Mydans, and Annalee Jacoby reported on the war for the company.

Life was pro-American and backed the war effort each week. In July 1942, Life launched its first art contest for soldiers and drew more than 1,500 entries, submitted by all ranks. Judges sorted out the best and awarded $1,000 in prizes. Life picked sixteen for reproduction in the magazine. Washington’s National Gallery agreed to put 117 on exhibition that summer.

The magazine employed the distinguished war photographer Robert Capa. A veteran of Colliers magazine, Capa was the sole photographer among the first wave of the D-Day invasion in Normandy, France, on June 6, 1944. A notorious controversy at the Life photography darkroom ensued after a mishap ruined dozens of Capa’s photos that were taken during the beach landing; the magazine claimed in its captions that the photos were fuzzy because Capa’s hands were shaking. He denied it; he later poked fun at Life by titling his memoir Slightly out of Focus. In 1954, Capa was killed while working for the magazine while covering the First Indochina War after stepping on a landmine.

Each week during World War II the magazine brought the war home to Americans; it had photographers in all theaters of war, from the Pacific to Europe.

In May 1950 the council of ministers in Cairo banned Life from Egypt forever. All issues on sale were confiscated. No reason was given, but Egyptian officials expressed indignation over the April 10, 1950, story about King Farouk of Egypt, entitled the “Problem King of Egypt.” The government considered it insulting to the country.

Life in the 1950s earned a measure of respect by commissioning work from top authors. After Life’s publication in 1952 of Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, the magazine contracted with the author for a four thousand-word piece on bullfighting. Hemingway sent the editors a ten thousand-word article, following his last visit to Spain in 1959 to cover a series of contests between two top matadors. The article was republished in 1985 as the novella The Dangerous Summer.[5]

In February 1953, just a few weeks after leaving office, President Harry S. Truman announced that Life magazine would handle all rights to his memoirs. Truman said it was his belief that by 1954 he would be able to speak more fully on subjects pertaining to the role his administration played in world affairs. Truman observed that Life editors had presented other memoirs with great dignity; he added that Life also made the best offer.

Life’s motto became, "To see Life; see the world." In the post-war years it published some of the most memorable images of events in the United States and the world. It also produced many popular science serials such as The World We Live In and The Epic of Man in the early 1950s.

The magazine was losing readers as the 1950s drew to a close. In May 1959 it announced plans to reduce its regular newsstand price to 19 cents a copy from 25 cents. With the increase in television sales and viewership, interest in news magazines was waning. Life would need to reinvent itself.

The end of an era (1960 - 1978)

In the 1960s the magazine was filled with color photos of movie stars, President John F. Kennedy and his family, the Vietnam War, and the Moon landing. Typical of the magazine’s editorial focus was a long 1964 feature on actress Elizabeth Taylor and her relationship to actor Richard Burton. Reporter Richard Meryman Jr. traveled with Taylor to New York City, California, and Paris. Life ran a six thousand-word first-person article on the screen star: “I’m not a ‘sex queen’ or a ‘sex symbol,’” Taylor said. “I don’t think I want to be one. Sex symbol kind of suggests bathrooms in hotels or something. I do know I’m a movie star and I like being a woman, and I think sex is absolutely gorgeous. But as far as a sex goddess, I don’t worry myself that way... Richard is a very sexy man. He’s got that sort of jungle essence that one can sense... When we look at each other, it’s like our eyes have fingers and they grab a hold... I think I ended up being the scarlet woman because of my rather puritanical up bringing and beliefs. I couldn’t just have a romance. It had to be a marriage.”[6]

In the 1960s, the magazine’s photographs featured those by Gordon Parks. “The camera is my weapon against the things I dislike about the universe and how I show the beautiful things about the universe,” Parks recalled in 2000. “I didn’t care about Life magazine. I cared about the people,” he said.[7]

In March 1967 Life won the 1967 National Magazine Award, chosen by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. The prestigious award paid tribute to the stunning photos coming out of the war in Southeast Asia, such as Henri Huet’s riveting series of a wounded medic that were published in January 1966. Increasingly, the photos that Life was printing of the war in Vietnam were searing images of death and loss.

However, despite the accolades the magazine continued to win, and publishing American’s mission to the Moon in 1969, circulation was lagging. It was announced in January 1971 that Life would reduce its circulation from 8.5 million to 7 million in an effort to offset shrinking advertising revenues. Exactly one year later, Life cut its circulation from 7 million to 5.5 million beginning with the January 14, 1972, issue. Publisher Gary Valk announced that Life was not losing money, but its costs were rising faster than its profits. Industry figures showed some 96 percent of its circulation went to mail subscribers and only four percent to newsstands. Valk was at the helm as publisher when hundreds lost their jobs. The end came when the weekly Life magazine shut down on December 8, 1972.

From 1972 to 1978, Time Inc. published ten Life Special Reports on such themes as “The Spirit of Israel,” “Remarkable American Women,” and “The Year in Pictures.” With a minimum of promotion, those issues sold between 500,000 and one million copies at cover prices of up to $2.

Life as a monthly, (1978 - 2000)

In 1978, Life reemerged as a monthly, and with this resurrection came a new, modified logo. Although still the familiar red rectangle with the white type, the new version was larger, and the lettering was closer together and the box surrounding it was smaller (this "new" larger logo would be used on every issue until July 1993).

Life continued for the next 22 years as a moderately-successful general interest news features magazine. In 1986, it decided to mark its 50th anniversary under the Time Inc. umbrella with a special issue showing every Life cover starting from 1936, which included the issues that were published during the six-year hiatus in the 1970s. The circulation in this era hovered around the 1.5 million mark. The cover price in 1986 was $2.25. The publisher at the time was Charles Whittingham.

Life was able to go back to war in 1991, and it did so just like in the 1940s. Four issues of this weekly Life in Time of War were published during the first Gulf War.

Hard times came to the magazine once again, and in February 1993 Life announced the magazine would be printed on smaller pages starting with its July issue. This issue would also mark the return of the original Life logo.

Also at this time, Life slashed advertising prices 35 percent in a bid to make the monthly publication more appealing to advertisers. The magazine reduced its circulation guarantee for advertisers by 12 percent in July 1993 to 1.5 million copies from the current 1.7 million. The publisher in this era was Nora McAniff; Life for the first time was the same format size as its longtime Time, Inc. sister publication, Fortune.

The magazine was back in the national consciousness upon the death in August 1995 of Alfred Eisenstaedt, the Life photographer whose pictures constitute some of the most enduring images of the twentieth century. Eisenstaedt’s photographs of the famous and infamous —Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini, Marilyn Monroe, Ernest Hemingway, the Kennedys, Sophia Loren—won him worldwide renown and 87 Life covers.

In 1999 the magazine was suffering financially, but still made news by compiling lists to round out the twentieth century. Life editors ranked its “100 Most Important Events of the Millennium.” This list has been criticized for being overly focused on Western achievements. The Chinese, for example, had invented movable type four centuries before Johannes Gutenberg, but with thousands of ideograms, found its use impractical. Life also published a list of the “100 Most Important People of the Millennium.” This list, too, was criticized for focusing on the West. Also, Thomas Edison's number one ranking was challenged since there were others whose inventions (the combustion engine, the automobile, electricity-making machines, for example), which had greater impact than Edison's. The top one hundred most important people list was further criticized for mixing world-famous names, such as Isaac Newton, Albert Einstein, Louis Pasteur, and Leonardo da Vinci, with numerous Americans largely unknown outside of the United States (18 Americans compared to 13 Italians and French, 12 English).

It appeared that the money-losing magazine was just hanging on to make it into the twenty-first century, and it did, but barely. In March 2000, Time, Inc. announced it would cease regular publication of Life with the May issue. “It’s a sad day for us here,” Don Logan, chairman and chief executive of Time, Inc., told CNNfn.com. “It was still in the black,” he said, noting that Life was increasingly spending more to maintain its monthly circulation level of approximately 1.5 million. “Life was a general interest magazine and since its reincarnation, it had always struggled to find its identity, to find its position in the marketplace,” Logan said.[8]

For Life subscribers, remaining subscriptions were honored with other Time, Inc. magazines, such as Time. And in January 2001, these subscribers received a special, Life-sized format of "The Year in Pictures" edition of Time magazine, which was in reality a Life issue disguised under a Time logo on the front (newsstand copies of this edition were actually published under the Life imprint).

While citing poor advertising sales and a rough climate for selling magazine subscriptions, Time Inc. executives said a key reason for closing the title in 2000 was to divert resources to the company’s other magazine launches that year, such as Real Simple.

Life Today

Life was absent from the U.S. market for only a few months, when it began publishing special newsstand "megazine" issues on topics such as 9/11 and the Holy Land in 2001. These issues, printed on thicker paper, were more like soft cover books than magazines.

Beginning in October 2004, it was revived for a second time. Life resumed weekly publication as a free supplement to U.S. newspapers. Life went into competition for the first time with the two industry heavyweights, Parade and USA Weekend. At its launch, it was distributed with more than 60 newspapers with a combined circulation of approximately 12 million. Among the newspapers to carry Life: New York Daily News, Los Angeles Times, Chicago Tribune, The Denver Post, and the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Time, Inc. made deals with several major newspaper publishers to carry the Life supplement, including Knight-Ridder and the McClatchy Company.

This current version of Life retained its trademark logo, but sports a new cover motto, “America’s Weekend Magazine.” It measures 9½ x 11½ inches and is printed on glossy paper in full-color. On September 15, 2006, Life was just 20 pages.

The magazine’s place in the history of photojournalism is considered its most important contribution to publishing. Photojournalism helped spur interest in current events by being more easily accessible than text only newspapers. Broader interest in current events is important in democracies such as the United States.

In popular culture

- “There are events which arouse such simple and obvious emotions that an AP cable or a photograph in Life magazine are enough and poetic comment is impossible.” — W. H. Auden, 1948. Poets at Work. Harcourt Brace.

- In 1937, Life commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design a house for a typical middle-income family. In 1993 the magazine revived the idea, launching a series of affordable houses designed by major American architects.

- In the classic 1954 motion picture directed by Alfred Hitchcock, Rear Window, the protagonist, portrayed by James Stewart, is a Life magazine photographer.

- In 1955, one year after his death, the Overseas Press Club created the Robert Capa Gold Medal. It is given annually to the photographer who provides the "best published photographic reporting from abroad, requiring exceptional courage and enterprise." Life contributors have won seven times, the last being Larry Burrows posthumously in 1971. Burrows died while working for Life in a helicopter crash in Vietnam with his friend and fellow photographer, Henri Huet.[9]

- In June 2004 it was revealed that former U.S. Army paratrooper Kelso Horne Sr.’s deathbed wish was for his ashes to be spread on the beach of Normandy, France. Horne was made world famous when Life featured his picture on its cover on Aug. 14, 1944, two months after he jumped with 13,000 other men into northern France on D-Day. The 82nd Airborne Division soldier became a symbol of the American fighting man. When he died sixty years later, his ashes were taken to France.[10]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1936. "Life: Dead & Alive." Time.

- ↑ 1937. "Pictorial to Sleep." Time.

- ↑ Hamblin, Dora. 1977. That Was the "Life". New York: W. W. Norton & Co.

- ↑ 1942. "Mansfield (Ohio)." News Journal.

- ↑ Palin, Michael. 1999. Michael Palin’s Hemingway Adventure. PBS.

- ↑ 1964. "Our Eyes Have Fingers." Time.

- ↑ 2000. The Rocky Mountain News.

- ↑ 2000. "Time Inc. to cease publication of Life magazine." CNNMoney.com. Retrieved February 10, 2007.

- ↑ Overseas Press Club Robert Capa Gold Medal. Retrieved February 8, 2007.

- ↑ 2004. Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Editors of Life Magazine. 2001. One Nation: America Remembers September 11, 2001. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0316525405

- Editors of Life Magazine. 2003. 100 Photographs That Changed the World. ISBN 1931933847

- Editors of Life Magazine. 2003. Life: Our National Parks: Celebrating America's Natural Splendor. ISBN 1931933316

- Editors of Life Magazine. 2005. Life: 100 Events That Shook Our World: A History in Pictures from the Last 100 Years. ISBN 1932994106

- Editors of Life Magazine. 2005. Life: The Year in Pictures 2005 (Life the Year in Pictures). ISBN 1932273522

- Editors of Life Magazine. 2006. Life: The Platinum Anniversary Collection: 70 Years of Extraordinary Photography. ISBN 1933405171

- Editors of Life Magazine. 2006. Life: Heaven on Earth: 100 Places to See in Your Lifetime . ISBN 1933405058

- Hamblin, Dora Jane. 1977. That was the Life. Deutsch. ISBN 0233969306

External links

All links retrieved October 25, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 05:31:57 | 15 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Life_magazine | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF