Bangladesh

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia | গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী বাংলাদেশ Gônoprojatontri Bangladesh | |

|---|---|

| Flag | Coat of Arms |

| Capital | Dhaka |

| Government | Parliamentary republic |

| Language | Bengali (Bangla) (official) |

| President | Abdul Hamid |

| Prime minister | Sheikh Hasina Wazed |

| Area | 55,599 sq mi |

| Population | 165,000,000 (2020) |

| GDP | $310,000,000,000 (2020) |

| GDP per capita | $1,879 (2020) |

| Currency | Taka |

Bangladesh (officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh) is a country in South Asia which is bordered by India and to a lesser extent Myanmar. It is a heavily Muslim country with a substantial Hindu minority. It was called East Pakistan, being the easternmost region of Pakistan before the Bangladeshi War of Independence in 1971, an armed conflict which lasted for 9 months and resulted in the creation of the nation of Bangladesh and resulted in it being severed from Pakistan. The national language is Bangla or Bengali.

Geography[edit]

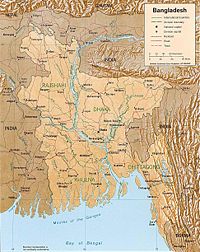

Bangladesh is a low-lying, riparian country located in South Asia with a largely marshy jungle coastline of 710 kilometers (440 mi.) on the northern littoral of the Bay of Bengal. Formed by a deltaic plain at the confluence of the Ganges (Padma), Brahmaputra (Jamuna), and Meghna Rivers and their tributaries, Bangladesh's alluvial soil is highly fertile but vulnerable to flood and drought. Hills rise above the plain only in the Chittagong Hill Tracts in the far southeast and the Sylhet division in the northeast. Straddling the Tropic of Cancer, Bangladesh has a subtropical monsoonal climate characterized by heavy seasonal rainfall, moderately warm temperatures, and high humidity. Natural calamities, such as floods, tropical cyclones, tornadoes, and tidal bores affect the country almost every year. Bangladesh also is affected by major cyclones—on average 16 times a decade.

Urbanization is proceeding rapidly, and it is estimated that only 30% of the population entering the labor force in the future will be absorbed into agriculture, although many will likely find other kinds of work in rural areas. The areas around Dhaka and Comilla are the most densely settled. The Sundarbans, an area of coastal tropical jungle in the southwest and last wild home of the Bengal Tiger, and the Chittagong Hill Tracts on the southeastern border with Burma and India, are the least densely populated.

People[edit]

The area that is now Bangladesh has a rich historical and cultural past, combining Dravidian, Indo-Aryan, Mongol/Mughul, Arab, Persian, Turkic, and west European cultures. Residents of Bangladesh, about 98% of whom are ethnic Bengali and speak Bangla, are called Bangladeshis. Urdu-speaking, non-Bengali Muslims of Indian origin, and various tribal groups, mostly in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, comprise the remainder. Most Bangladeshis (about 88.3%) are Muslims, but Hindus constitute a sizable (10.5%) minority. There also are a small number of Buddhists, Christians, and animists. English is spoken in urban areas and among the educated.

Sufi religious teachers succeeded in converting many Bengalis to Islam, even before the arrival of Muslim armies from the west. About 1200 AD, Muslim invaders established political control over the Bengal region. This political control also encouraged conversion to Islam. Since then, Islam has played a crucial role in the region's history and politics, with a Muslim majority emerging, particularly in the eastern region of Bengal.

- Population: 165 million.

- Annual growth rate: 1.7%.

- Ethnic groups: Bengali 98%, tribal groups, non-Bengali Muslims.

- Religions: Muslim 88.3%; Hindu 10.5%; Christian 0.3%, Buddhist 0.6%, others 0.3%.

- Languages: Bangla (official, also known as Bengali), English.

- Education: Attendance—61%. Literacy—62.66%.

- Health: Infant mortality rate (below 1)--65/1,000. Life expectancy—61 years (male), 62 years (female).

- Work force (60.3 million): Agriculture—62.3%; manufacturing and mining—7.6%; others—30.1%.

Government[edit]

The president, while chief of state, holds a largely ceremonial post; the real power is held by the prime minister, who is head of government. The president is elected by the legislature (Parliament) every 5 years. The president's circumscribed powers are substantially expanded during the tenure of a caretaker government. (Under the 13th Amendment, which Parliament passed in March 1996, a caretaker government assumes power temporarily to oversee general elections after dissolution of the Parliament.) In the caretaker government, the president has control over the Ministry of Defense, the authority to declare a state of emergency, and the power to dismiss the Chief Adviser and other members of the caretaker government. Once elections have been held and a new government and Parliament are in place, the president's powers and position revert to their largely ceremonial role. The Chief Adviser and other advisers to the caretaker government must be appointed within 15 days from the day the current Parliament expires.

The prime minister is appointed by the president. The prime minister must be a Member of Parliament (MP) whom the president feels commands the confidence of the majority of other MPs. The cabinet is composed of ministers selected by the prime minister and appointed by the president. At least 90% of the ministers must be MPs. The other 10% may be non-MP experts or "technocrats" who are not otherwise disqualified from being elected MPs. According to the constitution, the president can dissolve Parliament upon the written request of the prime minister.

The legislature is a unicameral, 300-seat body. All of its members are elected by universal suffrage at least every five years. Parliament amended the constitution in May 2004, making a provision for adding 45 seats reserved for women and to be distributed among political parties in proportion to their numerical strength in Parliament. The AL did not take its share of the reserved seats, arguing that they did not support the indirect election or nomination of women to fill these seats. Several women's groups also demanded direct election to fill the reserved seats for women.

Bangladesh's judiciary is a civil court system based on the British model; the highest court of appeal is the appellate court of the Supreme Court. At the local government level, the country is divided into divisions, districts, subdistricts, unions, and villages. Local officials are elected at the union level and selected at the village level. All larger administrative units are run by members of the civil service.

Principal Government Officials[edit]

- President—Abdul Hamid

- Prime Minister—Sheikh Hasina

- Speaker of the Jatiya Sangsad—Shirin Sharmin Chaudhury

- Deputy Speaker—Fazle Rabbi Miah

- Leader of the Opposition—Rowshan Ershad

- Chief Justice—Syed Mahmud Hossain

Political Conditions[edit]

Despite serious problems related to a dysfunctional political system, weak governance, and pervasive corruption, Bangladesh remains one of the few democracies in the Muslim world. Bangladeshis regard democracy as an important legacy of their bloody war for independence, and vote in large numbers. However, the practice and understanding of democratic concepts is often shallow. The current government has banned all political activities and has yet to set a date for elections or its own departure from office. Bangladesh is generally a force for moderation in international forums, and it is also a long-time leader in international peacekeeping operations. Its activities in international organizations, with other governments, and its regional partners to promote human rights, democracy, and free markets are coordinated and high-profile. In May 2005, Bangladesh became a member of the United Nations Human Rights Council.

Bangladesh lies at the strategic crossroads of South and Southeast Asia. Potential terrorist movements and activities in or through Bangladesh pose a potentially serious threat to India, Nepal, Bhutan, and Burma, as well as Bangladesh itself. The Bangladesh Government routinely denies Indian allegations that Indian insurgents in northeast India operate out of Bangladesh and that extremist Islamist forces are overwhelming Bangladesh's traditionally moderate character. It also denies there is any international terrorist presence in Bangladesh. The Bangladesh Government, however, banned a number of Islamic extremist groups in recent years. In February 2002, the government banned Shahdat al Hiqma, in February 2005 it banned Jagrata Muslim Janata, Bangladesh (JMJB) and Jama’atul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB), and in October 2005 it banned Harkatul Jehad Al Islami (HUJI). Following the August 17, 2005 serial bombings in the country, the government launched a crackdown on the extremists. In 2006, seven senior JMB leaders were sentenced to death for their role in the 2005 murder of two judges. Six of the seven were executed in March 2007; another leader was tried and sentenced to death in absentia in the same case. In May 2005, the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) killed six alleged Indian rebels in a raid on a house near the border with India in north-eastern Maulvibazar district. In June 2006, army and RAB personnel killed 10 gunrunners, who media reports described as suspected Indian insurgents, in a remote forest in southeastern Rangamati Hill district. Given its size and location, a major crisis in Bangladesh could have important consequences for regional stability, particularly if significant refugee movements ensue.

Human rights[edit]

Today, extensive human rights violations by the Bangladesh Government are reported by Human Rights Groups. The more egalitarian Awami League government was ousted and replaced by the Islamic Fundamentalist government of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party [1][2][3] [4][5]

Dr. Janice Shaw Crouse of Concerned Women for America's (CWA) Beverly LaHaye Institute and CWA's expert in anti-trafficking efforts, called upon the government of Bangladesh in June 2007 to end the house arrest of Sigma Huda, the United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on trafficking in persons. Suda has made attempts to attend official meetings in New York, Belarus and Sweden but has been prevented from leaving the country.

Crouse said, “Sigma Huda provides an international voice for those women and children who are victimized and exploited by criminals who use human beings as commodities and profit from the odious modern day slave trade. Efforts to censor her reports or to curtail her work is a crime against human rights and violates the immunity that she receives as a United Nations’ diplomat commissioned to protect some of the most vulnerable people around the world.”

Crouse added, “CWA calls on President Bush — who is at the forefront in fighting trafficking in persons and who calls such trafficking ‘modern day slavery’ — to use his credibility on the issue of sex trafficking to enlist the other leaders who are attending the G8 meeting in Germany to urge the caretaker government of Bangladesh to free Miss Huda to fulfill her responsibilities as Special Rapporteur. CWA also calls on the United Nations’ Secretary General Ban Ki Moon to use the authority of the United Nations to ensure that its Special Rapporteur is able to carry out her duties without harassment or interference.” [1]

Foreign Relations[edit]

Bangladesh pursues a moderate foreign policy that places heavy reliance on multinational diplomacy, especially at the United Nations.

Participation in Multilateral Organizations Bangladesh was admitted to the United Nations in 1974 and was elected to a Security Council term in 1978 and again for a 2000-01 term. Then Foreign Minister Choudhury served as president of the 41st UN General Assembly in 1986. The government has participated in numerous international conferences, especially those dealing with population, food, development, and women's issues. In 1982-83, Bangladesh played a constructive role as chairman of the "Group of 77," an informal association encompassing most of the world's developing nations. It has taken a leading role in the "Group of 48" developing countries and the "Developing-8" group of countries. It is also a participant in the activities of the Non-aligned Movement.

Since 1975, Bangladesh has sought close relations with other Islamic states and a role among moderate members of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC). In 1983, Bangladesh hosted the foreign ministers meeting of the OIC. The government also has pursued the expansion of cooperation among the nations of South Asia, bringing the process—an initiative of former President Ziaur Rahman—through its earliest, most tentative stages to the formal inauguration of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) at a summit gathering of South Asian leaders in Dhaka in December 1985. Bangladesh hosted the last SAARC summit in November 2005, and Prime Minister Khaleda Zia had reassumed its chairmanship. In the latest summit, Bangladesh has participated in a wide range of ongoing SAARC regional activities. The head of the current caretaker government participated in the April 2007 SAARC summit in India.

In recent years, Bangladesh has played a significant role in international peacekeeping activities. Several thousand Bangladeshi military personnel are deployed overseas on peacekeeping operations. Under UN auspices, Bangladeshi troops have served or are serving in Sierra Leone, Somalia, Rwanda, Mozambique, Kuwait, Ethiopia-Eritrea, Kosovo, East Timor, Georgia, Congo, Côte d'Ivoire and Western Sahara, Bosnia, and Haiti. Bangladesh responded quickly to President Clinton's 1994 request for troops and police for the multinational force for Haiti and provided the largest non-U.S. contingent.

Bilateral Relations With Other Nations[edit]

Bangladesh is bordered on the west, north, and east by a 2,400-kilometer land frontier with India, and on the southeast by a land and water frontier (193 kilometers) with Burma.

India[edit]

India is Bangladesh's most important neighbor. Geographic, cultural, historic, and commercial ties are strong, and both countries recognize the importance of good relations. During and immediately after Bangladesh's struggle for independence from Pakistan in 1971, India assisted refugees from East Pakistan, intervened militarily to help bring about the independence of Bangladesh, and furnished relief and reconstruction aid.

Indo-Bangladesh relations are often strained, and many Bangladeshis feel India likes to play "big brother" to smaller neighbors, including Bangladesh. Bilateral relations warmed in 1996, due to a softer Indian foreign policy and the new Awami League government. A 30-year water-sharing agreement for the Ganges River was signed in December 1996, after an earlier bilateral water-sharing agreement for the Ganges River lapsed in 1988. Bangladesh remains extremely concerned about a proposed Indian river linking project, which the government says could turn large parts of Bangladesh into a desert The Bangladesh Government and tribal insurgents signed a peace accord in December 1997, which allowed for the return of tribal refugees who had fled into India, beginning in 1986, to escape violence caused by an insurgency in their homeland in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. The implementation of most parts of this agreement has stalled, and the army maintains a strong presence in the Hill Tracts. Arms smuggling and reported opium poppy cultivation are concerns in this area. Occasional skirmishes between Bangladeshi and Indian border forces sometimes escalate and seriously disrupt bilateral relations.

The ruling party views the Indian Government as a major benefactor of the opposition Awami League, and blames negative international media coverage of Bangladesh on alleged Indian manipulation. Prime Minister Khaleda Zia, however, visited the Indian capital in March 2006 and reviewed bilateral relations with her Indian counterpart. Two agreements—The Revised Trade Agreement and the Agreement on Mutual Cooperation for Preventing Illicit Drug Trafficking in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances and Related Matters—were signed between the two countries during this visit. Indian Foreign Minister Pranab Mukherjee met with Chief Adviser Ahmed in Dhaka on February 26, 2007. Mukherjee invited Ahmed to the April 3–4, 2007, SAARC summit in Delhi, and both sides pledged to put Bangladesh-India relations on "an irreversible higher trajectory."

Pakistan[edit]

Bangladesh enjoys warm relations with Pakistan, despite the strained early days of their relationship. Landmarks in their reconciliation are:

- An August 1973 agreement between Bangladesh and Pakistan on the repatriation of numerous individuals, including 90,000 Pakistani prisoners of war stranded in Bangladesh as a result of the 1971 conflict;

- A February 1974 accord by Bangladesh and Pakistan on mutual recognition followed more than 2 years later by establishment of formal diplomatic relations;

- The organization by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) of an airlift that moved almost 250,000 Bengalis from Pakistan to Bangladesh, and non-Bengalis from Bangladesh to Pakistan; and

- Exchanges of high-level visits, including a visit by Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto to Bangladesh in 1989 and visits by Prime Minister Zia to Pakistan in 1992 and in 1995.

- President Pervez Musharraf visited Bangladesh in 2002.

- Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz visited Bangladesh in 2004.

- Prime Minister Khaleda Zia visited Pakistan in 2006.

Still to be resolved are the division of assets from the pre-1971 period and the status of more than 250,000 non-Bengali Muslims (known as "Biharis") remaining in Bangladesh but seeking resettlement in Pakistan.

Burma[edit]

Bilateral ties with Burma are good, despite occasional border strains and an influx of more than 270,000 Muslim refugees (known as "Rohingya") from predominantly Buddhist Burma. As a result of bilateral discussions, and with the cooperation and assistance of the UNHCR, most of the Rohingya refugees have now returned to Burma. As of 2007, about 20,000 refugees remain in camps in southern Bangladesh. Thousands of other Burmese, not officially registered as refugees, are squatting on the bank of the river Naaf or living in Bangladeshi villages in the southeastern tip. Bangladesh and Burmese officials are negotiating a deal to establish direct road link between the capitals of the two countries.

Former Soviet Union[edit]

The former Soviet Union supported India's actions during the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war and was among the first to recognize Bangladesh. The U.S.S.R. initially contributed considerable relief and rehabilitation aid to the new nation. After Sheikh Mujib was assassinated in 1975 and replaced by military regimes, however, Soviet-Bangladesh relations cooled.

In 1989, the U.S.S.R. ranked 14th among aid donors to Bangladesh. The Soviets focused on the development of electrical power, natural gas and oil, and maintained active cultural relations with Bangladesh. They financed the Ghorasal thermal power station—the largest in Bangladesh. Recently, Russia has conducted an aggressive military sales effort in Dhaka and has succeeded with a $124-million deal for eight MiG-29 fighters. Bangladesh began to open diplomatic relations with the newly independent Central Asian states in 1992.

China[edit]

China traditionally has been more important to Bangladesh than the former U.S.S.R., even though China supported Pakistan in 1971. As Bangladesh's relations with the Soviet Union and India cooled in the mid-1970s, and as Bangladesh and Pakistan became reconciled, China's relations with Bangladesh grew warmer. An exchange of diplomatic missions in February 1976 followed an accord on recognition in late 1975.

Since that time, relations have grown stronger, centering on trade, cultural activities, military and civilian aid, and exchanges of high-level visits, beginning in January 1977 with President Zia's trip to Beijing. The largest and most visible symbol of bilateral amity is the Bangladesh-China "Friendship Bridge," completed in 1989 near Dhaka, as well as the extensive military hardware in the Bangladesh inventory and warm military relations between the two countries. In the 1990s, the Chinese also built two 210-megawatt power plants outside of Chittagong; mechanical faults in the plants cause them to frequently shut down for days at a time, heightening the country's power shortage. In April 2005, Bangladesh and China signed nine memoranda of understanding on trade and other issues during the visit to Dhaka of Prime Minister Wen. The opening of a Taiwanese trade center in Dhaka in 2004 displeased China, but the Bangladesh government moved quickly to repair the crack and closed the trade center. In August 2005 Prime Minister Khalda Zia visited China.

Other countries in South Asia[edit]

Bangladesh maintains friendly relations with Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka and strongly opposed the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Bangladesh and Nepal recently agreed to facilitate land transit between the two countries. Bangladesh is considering importing electricity from Nepal and Bhutan through India to meet its energy shortfall.

Defense[edit]

The Bangladesh Army, Navy, and Air Force are composed of regular military members. The 110,000-member, seven-division army is modeled and organized along British lines, similar to other armies on the Indian subcontinent. However, it has adopted U.S. Army tactical planning procedures, training management techniques, and noncommissioned officer educational systems. It also is eager to improve its peacekeeping operations capabilities and is working with the U.S. military in that area. The United States gave the Bangladesh Air Force four U.S. C-130 B transport aircraft in 2001 under the excess defense article (EDA) program. These aircraft will improve the military's disaster response and peacekeeping capabilities. The Bangladesh Navy is mostly limited to coastal patrolling, but in 2001 it paid to have an ULSAN-class frigate built in South Korea.

In addition to traditional defense roles, the military has been called on to provide support to civil authorities for disaster relief and internal security. Since the proclamation of the state of emergency on January 11, 2007, the military has played a central role in the formulation and execution of key government strategies, including the anti-corruption campaign. The Bangladesh Air Force and Navy, with about 7,000 personnel each, perform traditional military missions. A Coast Guard has been formed, under the home ministry, to play a stronger role in the area of anti-smuggling, anti-piracy, and protection of offshore resources. Recognition of economic and fiscal constraints has led to the establishment of several paramilitary and auxiliary forces, including the 40,000-member Bangladesh rifles; the Ansars and village defense parties organization, which claim 64 members in every village in the country; and a 5,000-member specialized police unit known as the armed police. In 2004, a new police unit called the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) was constituted with personnel drawn from the military and different law enforcement agencies. RAB is designed to fight hardcore criminal gangs. Bangladesh Rifles, under the authority of the home ministry, are commanded by army officers who are seconded to the organization.

In addition to in-country military training, some advanced and technical training is done abroad, including grant aid training in the United States. China, Pakistan, and Eastern Europe are the major defense suppliers to Bangladesh, but military leaders are trying to find affordable alternatives to Chinese equipment.

A 2,300-member Bangladesh Army contingent served with coalition forces during the 1991 Gulf war. As of February 28, 2007, Bangladesh's 9,653 peacekeepers deployed around the world made it the second-largest troop contributor to international peacekeeping operations. Troops are deployed in Côte d'Ivoire, Liberia, Sudan, Congo, Ethiopia and Eritrea, Western Sahara, Georgia, East Timor, Kosovo, Sierra Leone, and Afghanistan.

Economy[edit]

Although one of the world's poorest and most densely populated countries, Bangladesh has made major strides to meet the food needs of its increasing population, through increased domestic production augmented by imports. The land is devoted mainly to rice and jute cultivation, although wheat production has increased in recent years; the country is largely self-sufficient in rice production. Nonetheless, an estimated 10% to 15% of the population faces serious nutritional risk. Bangladesh's predominantly agricultural economy depends heavily on an erratic monsoonal cycle, with periodic flooding and drought. Although improving, infrastructure to support transportation, communications, and power supply is poorly developed. Bangladesh is limited in its reserves of coal and oil, and its industrial base is weak. However, the country's main endowments include its vast human resource base, rich agricultural land, relatively abundant water, and substantial reserves of natural gas.

Since independence in 1971, Bangladesh has received more than $30 billion in grant aid and loan commitments from foreign donors, about $15 billion of which has been disbursed. Major donors include the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, the UN Development Program, the United States, Japan, Saudi Arabia, and west European countries. Bangladesh historically has run a large trade deficit, financed largely through aid receipts and remittances from workers overseas. Foreign reserves dropped markedly in 2001 but appear to have now stabilized in the $3 to $4 billion range (or about 3 months import cover). On January 7, 2007, reserves stood at $3.73 billion.

Moves Toward a Market Economy[edit]

Following the violent events of 1971 during the fight for independence, Bangladesh—with the help of large infusions of donor relief and development aid—slowly began to turn its attention to developing new industrial capacity and rehabilitating its economy. The static economic model adopted by its early leadership, however—including the nationalization of much of the industrial sector—resulted in inefficiency and economic stagnation. Beginning in late 1975, the government gradually gave greater scope to private sector participation in the economy, a pattern that has continued. A few state-owned enterprises have been privatized, but many, including major portions of the banking and jute sectors, remain under government control. Population growth, inefficiency in the public sector, a resistance to developing the country's richest natural resources, and limited capital have all continued to restrict economic growth.

In the mid-1980s, there were encouraging, if halting, signs of progress. Economic policies aimed at encouraging private enterprise and investment, denationalizing public industries, reinstating budgetary discipline, and liberalizing the import regime were accelerated. From 1991 to 1993, the government successfully followed an enhanced structural adjustment facility (ESAF) with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) but failed to follow through on reforms in large part because of a preoccupation with the government's domestic political troubles. In the late 1990s the government's economic policies became more entrenched, and some of the early gains were lost, which was highlighted by a precipitous drop in foreign direct investment in 2000 and 2001. In June 2003 the IMF approved 3-year, $490-million plan as part of the Poverty Reduction and Growth Facility (PRGF) for Bangladesh that aimed to support the government's economic reform program up to 2006. Seventy million dollars was made available immediately. In the same vein the World Bank approved $536 million in interest-free loans.

Efforts to achieve Bangladesh's macroeconomic goals have been problematic. The privatization of public sector industries has proceeded at a slow pace—due in part to worker unrest in affected industries—although on June 30, 2002, the government took a bold step as it closed down the Adamjee Jute Mill, the country's largest and most costly state-owned enterprise. The government also has proven unable to resist demands for wage hikes in government-owned industries. Access to capital is impeded. State-owned banks, which control about three-fourths of deposits and loans, carry classified loan burdens of about 50%.

The IMF and World Bank predict GDP growth over the next 5 years will be about 6.0%, well short of the 8%-9% that they feel is needed to lift Bangladesh out of its severe poverty. The initial impact of the end of quotas under the Multi-Fiber Arrangement has been positive for Bangladesh, with continuing investment in the ready-made garment sector, which is experiencing 20%-25% export growth. Downward price pressure means Bangladesh must continue to cut final delivered costs if it is to remain competitive in the world market. Foreign investors in a broad range of sectors are increasingly frustrated with the politics of confrontation, the level of corruption, and the slow pace of reform. While investors view favorably recent steps by the interim government to address corruption, governance, and infrastructure issues, most believe it is too early to assess the long-term impact of these developments.

Agriculture[edit]

Most Bangladeshis earn their living from agriculture. Although rice and jute are the primary crops, maize and vegetables are assuming greater importance. Due to the expansion of irrigation network, some wheat producers have switched to cultivation of maize which is used mostly as poultry feed. Tea is grown in the northeast. Because of Bangladesh's fertile soil and normally ample water supply, rice can be grown and harvested three times a year in many areas. Due to a number of factors, Bangladesh's labor-intensive agriculture has achieved steady increases in food grain production despite the often unfavorable weather conditions. These include better flood control and irrigation, a generally more efficient use of fertilizers, and the establishment of better distribution and rural credit networks. With 28.8 million metric tons produced in 2005-2006 (July–June), rice is Bangladesh's principal crop. By comparison, wheat output in 2005-2006 was 9 million metric tons. Population pressure continues to place a severe burden on productive capacity, creating a food deficit, especially of wheat. Foreign assistance and commercial imports fill the gap. Underemployment remains a serious problem, and a growing concern for Bangladesh's agricultural sector will be its ability to absorb additional manpower. Finding alternative sources of employment will continue to be a daunting problem for future governments, particularly with the increasing numbers of landless peasants who already account for about half the rural labor force.

Industry and Investment[edit]

Fortunately for Bangladesh, many new jobs—1.8 million, mostly for women—have been created by the country's dynamic private readymade garment industry, which grew at double-digit rates through most of the 1990s. The labor-intensive process of shipbreaking for scrap has developed to the point where it now meets most of Bangladesh's domestic steel needs. Other industries include sugar, tea, leather goods, newsprint, pharmaceutical, and fertilizer production. The country has done less well, however, in expanding its export base—garments account for more than three-fourths of all exports, dwarfing the country's historic cash crop, jute, along with leather, shrimp, pharmaceuticals, and ceramics.

Despite the country's politically motivated general strikes, poor infrastructure, and weak financial system, Bangladeshi entrepreneurs have shown themselves adept at competing in the global garments marketplace. Bangladesh exports significant amounts of garments and knitwear to the U.S. and the European Union (EU) market. As noted, the initial impact of the end of quotas on Bangladesh's ready-made garment industry has been positive. Downward price pressures, however, mean Bangladesh must continue to cut final delivered costs if it is to remain competitive in the world market. Bangladesh has been a world leader in its efforts to end the use of child labor in garment factories. On July 4, 1995, the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers Export Association, International Labor Organization, and UNICEF signed a memorandum of understanding on the elimination of child labor in the garment sector. Implementation of this pioneering agreement began in fall 1995, and by the end of 2001, child labor in the garment trade virtually had been eliminated.

The Bangladesh Government continues to court foreign investment, something it did fairly well in the 1990s in private power generation and gas exploration and production, as well as in other sectors such as cellular telephony, textiles, and pharmaceuticals. In 1989, the same year it signed a bilateral investment treaty with the United States, it established a board of investment to simplify approval and start-up procedures for foreign investors, although in practice the board has done little to increase investment. Bangladesh also has established successful export processing zones in Chittagong (1983), Dhaka (1994) and Comilla (2000), and has given the private sector permission to build and operate competing export promotion zones (EPZs).

The most important reforms Bangladesh should make to be able to compete in a global economy are to privatize the state-owned enterprises (SOEs), deregulate and promote foreign investment in high-potential industries like energy and telecommunications, and take decisive steps toward combating corruption and strengthening rule of law.

History[edit]

Bengal was absorbed into the Mughul Empire in the 16th century, and Dhaka, the seat of a nawab (the representative of the emperor), gained some importance as a provincial center. But it remained remote and thus a difficult to govern region—especially the section east of the Brahmaputra River—outside the mainstream of Mughul politics. Portuguese traders and missionaries were the first Europeans to reach Bengal in the latter part of the 15th century. They were followed by representatives of the Dutch, the French, and the British East India Companies. By the end of the 17th century, the British presence on the Indian subcontinent was centered in Calcutta. During the 18th and 19th centuries, the British gradually extended their commercial contacts and administrative control beyond Calcutta to Bengal. In 1859, the British Crown replaced the East India Company, extending British dominion from Bengal, which became a region of India, in the east to the Indus River in the west.

The rise of nationalism throughout British-controlled India in the late 19th century resulted in mounting animosity between the Hindu and Muslim communities. In 1885, the All-India National Congress was founded with Indian and British membership. Muslims seeking an organization of their own founded the All-India Muslim League in 1906. Although both the League and the Congress supported the goal of Indian self-government within the British Empire, the two parties were unable to agree on a way to ensure the protection of Muslim political, social, and economic rights. The subsequent history of the nationalist movement was characterized by periods of Hindu-Muslim cooperation, as well as by communal antagonism. The idea of a separate Muslim state gained increasing popularity among Indian Muslims after 1936, when the Muslim League suffered a decisive defeat in the first elections under India's 1935 constitution. In 1940, the Muslim League called for an independent state in regions where Muslims were in the majority. Campaigning on that platform in provincial elections in 1946, the League won the majority of the Muslim seats contested in Bengal. Widespread communal violence followed, especially in Calcutta.

When British India was partitioned and the independent dominions of India and Pakistan were created in 1947, the region of Bengal was divided along religious lines. The predominantly Muslim eastern half was designated East Pakistan—and made part of the newly independent Pakistan—while the predominantly Hindu western part became the Indian state of West Bengal. Pakistan's history from 1947 to 1971 was marked by political instability and economic difficulties. Dominion status was rejected in 1956 in favor of an "Islamic republic within the Commonwealth." Attempts at civilian political rule failed, and the government imposed martial law between 1958 and 1962, and again between 1969 and 1971.

Almost from the advent of independent Pakistan in 1947, frictions developed between East and West Pakistan, which were separated by more than 1,000 miles of Indian territory. East Pakistanis felt exploited by the West Pakistan-dominated central government. Linguistic, cultural, and ethnic differences also contributed to the estrangement of East from West Pakistan. Bengalis strongly resisted attempts to impose Urdu as the sole official language of Pakistan. Responding to these grievances, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1948 formed a students' organization called the Chhatra League. In 1949, Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani and some other Bengali leaders formed the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League (AL), a party designed mainly to promote Bengali interests. This party dropped the word Muslim from its name in 1955 and came to be known as Awami League. Mujib became president of the Awami League in 1966 and emerged as leader of the Bengali autonomy movement. In 1966, he was arrested for his political activities.

After the Awami League won almost all the East Pakistan seats of the Pakistan national assembly in 1970-71 elections, West Pakistan opened talks with the East on constitutional questions about the division of power between the central government and the provinces, as well as the formation of a national government headed by the Awami League. The talks proved unsuccessful, however, and on March 1, 1971, Pakistani President Yahya Khan indefinitely postponed the pending national assembly session, precipitating massive civil disobedience in East Pakistan. Mujib was arrested again; his party was banned, and most of his aides fled to India and organized a provisional government. On March 26, 1971, following a bloody crackdown by the Pakistan Army, Bengali nationalists declared an independent People's Republic of Bangladesh. As fighting grew between the army and the Bengali mukti bahini ("freedom fighters"), an estimated 10 million Bengalis, mainly Hindus, sought refuge in the Indian states of Assam and West Bengal. On April 17, 1971, a provisional government was formed in Meherpur district in western Bangladesh bordering India with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, who was in prison in Pakistan, as president, Syed Nazrul Islam as Acting President, and Tajuddin Ahmed as Prime Minister.

The crisis in East Pakistan produced new strains in Pakistan's troubled relations with India. The two nations had fought a war in 1965, mainly in the west, but the refugee pressure in India in the fall of 1971 produced new tensions in the east. Indian sympathies lay with East Pakistan, and in November, India intervened on the side of the Bangladeshis. On December 16, 1971, Pakistani forces surrendered, and Bangladesh—meaning "Bengal country"—was born; the new country became a parliamentary democracy under a 1972 constitution.

The first government of the new nation of Bangladesh was formed in Dhaka with Justice Abu Sayeed Choudhury as president, and Sheikh Mujibur Rahman ("Mujib")--who was released from Pakistani prison in early 1972—as Prime Minister.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, 1972-75[edit]

Mujib came to office with immense personal popularity but had difficulty transforming this popular support into the political strength needed to function as head of government. The new constitution, which came into force in December 1972, created a strong executive prime minister, a largely ceremonial presidency, an independent judiciary, and a unicameral legislature on a modified Westminster model. The 1972 constitution adopted as state policy the Awami League's (AL) four basic principles of nationalism, secularism, socialism, and democracy.

The first parliamentary elections held under the 1972 constitution were in March 1973, with the Awami League winning a massive majority. No other political party in Bangladesh's early years was able to duplicate or challenge the League's broad-based appeal, membership, or organizational strength. Relying heavily on experienced civil servants and members of the Awami League, the new Bangladesh Government focused on relief, rehabilitation, and reconstruction of the economy and society. Economic conditions remained precarious, however. In December 1974, Mujib decided that continuing economic deterioration and mounting civil disorder required strong measures. After proclaiming a state of emergency, Mujib used his parliamentary majority to win a constitutional amendment limiting the powers of the legislative and judicial branches, establishing an executive presidency, and instituting a one-party system, the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL), which all members of Parliament (and senior civil and military officials) were obliged to join.

Despite some improvement in the economic situation during the first half of 1975, implementation of promised political reforms was slow, and criticism of government policies became increasingly centered on Mujib. In August 1975, Mujib, and most of his family, were assassinated by mid-level army officers. His daughters, Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, were out of the country. A new government, headed by former Mujib associate Khandakar Moshtaque, was formed.

Ziaur Rahman, 1975-81[edit]

Successive military coups resulted in the emergence of Army Chief of Staff Gen. Ziaur Rahman ("Zia") as strongman. He pledged the army's support to the civilian government headed by President Chief Justice Sayem. Acting at Zia's behest, Sayem dissolved Parliament, promising fresh elections in 1977, and instituted martial law.

Acting behind the scenes of the Martial Law Administration (MLA), Zia sought to invigorate government policy and administration. While continuing the ban on political parties, he sought to revitalize the demoralized bureaucracy, to begin new economic development programs, and to emphasize family planning. In November 1976, Zia became Chief Martial Law Administrator (CMLA) and assumed the presidency upon Sayem's retirement 5 months later, promising national elections in 1978.

As President, Zia announced a 19-point program of economic reform and began dismantling the MLA. Keeping his promise to hold elections, Zia won a 5-year term in June 1978 elections, with 76% of the vote. In November 1978, his government removed the remaining restrictions on political party activities in time for parliamentary elections in February 1979. These elections, which were contested by more than 30 parties, marked the culmination of Zia's transformation of Bangladesh's Government from the MLA to a democratically elected, constitutional one. The AL and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), founded by Zia, emerged as the two major parties.

In May 1981, Zia was assassinated in Chittagong by dissident elements of the military. The attempted coup never spread beyond that city, and the major conspirators were either taken into custody or killed. In accordance with the constitution, Vice President Justice Abdus Sattar was sworn in as acting president. He declared a new national emergency and called for election of a new president within 6 months—an election Sattar won as the BNP's candidate. President Sattar sought to follow the policies of his predecessor and retained essentially the same cabinet, but the army stepped in once again.

Hussain Mohammed Ershad, 1982-90[edit]

Army Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. H.M. Ershad assumed power in a bloodless coup in March 1982. Like his predecessors, Ershad suspended the constitution and—citing pervasive corruption, ineffectual government, and economic mismanagement—declared martial law. The following year, Ershad assumed the presidency, retaining his positions as army chief and CMLA. During most of 1984, Ershad sought the opposition parties' participation in local elections under martial law. The opposition's refusal to participate, however, forced Ershad to abandon these plans. Ershad sought public support for his regime in a national referendum on his leadership in March 1985. He won overwhelmingly, although turnout was small. Two months later, Ershad held elections for local council chairmen. Pro-government candidates won a majority of the posts, setting in motion the President's ambitious decentralization program. Political life was further liberalized in early 1986, and additional political rights, including the right to hold large public rallies, were restored. At the same time, the Jatiya (National) Party, designed as Ershad's political vehicle for the transition from martial law, was established.

Despite a boycott by the BNP, led by President Zia's widow, Begum Khaleda Zia, parliamentary elections were held on schedule in May 1986. The Jatiya Party won a modest majority of the 300 elected seats in the National Assembly. The participation of the Awami League—led by the late President Mujib's daughter, Sheikh Hasina Wajed—lent the elections some credibility, despite widespread charges of voting irregularities.

Ershad resigned as Army Chief of Staff and retired from military service in preparation for the presidential elections, scheduled for October. Protesting that martial law was still in effect, both the BNP and the AL refused to put up opposing candidates. Ershad easily outdistanced the remaining candidates, taking 84% of the vote. Although Ershad's government claimed a turnout of more than 50%, opposition leaders, and much of the foreign press, estimated a far lower percentage and alleged voting irregularities.

Ershad continued his stated commitment to lift martial law. In November 1986, his government mustered the necessary two-thirds majority in the National Assembly to amend the constitution and confirm the previous actions of the martial law regime. The President then lifted martial law, and the opposition parties took their elected seats in the National Assembly.

In July 1987, however, after the government hastily pushed through a controversial legislative bill to include military representation on local administrative councils, the opposition walked out of Parliament. Passage of the bill helped spark an opposition movement that quickly gathered momentum, uniting Bangladesh's opposition parties for the first time. The government began to arrest scores of opposition activists under the country's Special Powers Act of 1974. Despite these arrests, opposition parties continued to organize protest marches and nationwide strikes. After declaring a state of emergency, Ershad dissolved Parliament and scheduled fresh elections for March 1988.

All major opposition parties refused government overtures to participate in these polls, maintaining that the government was incapable of holding free and fair elections. Despite the opposition boycott, the government proceeded. The ruling Jatiya Party won 251 of the 300 seats. The Parliament, while still regarded by the opposition as an illegitimate body, held its sessions as scheduled, and passed a large number of bills, including, in June 1988, a controversial constitutional amendment making Islam Bangladesh's state religion and provision for setting up High Court benches in major cities outside of Dhaka. While Islam remains the state religion, the provision for decentralizing the High Court division has been struck down by the Supreme Court.

By 1989, the domestic political situation in the country seemed to have quieted. The local council elections were generally considered by international observers to have been less violent and more free and fair than previous elections. However, opposition to Ershad's rule began to regain momentum, escalating by the end of 1990 in frequent general strikes, increased campus protests, public rallies, and a general disintegration of law and order.

On December 6, 1990, Ershad offered his resignation. On February 27, 1991, after 2 months of widespread civil unrest, an interim government headed by Acting President Chief Justice Shahabuddin Ahmed oversaw what most observers believed to be the nation's most free and fair elections to that date.

Khaleda Zia, 1991-96[edit]

The center-right BNP won a plurality of seats and formed a government with support from the Islamic fundamentalist party Jamaat-I-Islami, with Khaleda Zia, widow of Ziaur Rahman, obtaining the post of prime minister. Only four parties had more than 10 members elected to the 1991 Parliament: The BNP, led by Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia; the AL, led by Sheikh Hasina; the Jamaat-I-Islami (JI), led by Ghulam Azam; and the Jatiya Party (JP), led by acting chairman Mizanur Rahman Choudhury while its founder, former President Ershad, served out a prison sentence on corruption charges. The electorate approved still more changes to the constitution, formally re-creating a parliamentary system and returning governing power to the office of the prime minister, as in Bangladesh's original 1972 constitution. In October 1991, members of Parliament elected a new head of state, President Abdur Rahman Biswas.

In March 1994, controversy over a parliamentary by-election, which the opposition claimed the government had rigged, led to an indefinite boycott of Parliament by the entire opposition. The opposition also began a program of repeated general strikes to press its demand that Khaleda Zia's government resign and a caretaker government supervise a general election. Efforts to mediate the dispute, under the auspices of the Commonwealth Secretariat, failed. After another attempt at a negotiated settlement failed narrowly in late December 1994, the opposition resigned en masse from Parliament. The opposition then continued a campaign of marches, demonstrations, and strikes in an effort to force the government to resign. The opposition, including the Awami League's Sheikh Hasina, pledged to boycott national elections scheduled for February 15, 1996.

In February, Khaleda Zia was re-elected by a landslide in voting boycotted and denounced as unfair by the three main opposition parties. In March 1996, following escalating political turmoil, the sitting Parliament enacted a constitutional amendment to allow a neutral caretaker government to assume power and conduct new parliamentary elections; former Chief Justice Mohammed Habibur Rahman was named Chief Adviser (a position equivalent to prime minister) in the interim government. New parliamentary elections were held in June 1996 and the Awami League won plurality and formed the government with support from the Jatiya Party led by deposed president Ershad; party leader Sheikh Hasina became Prime Minister.

Sheikh Hasina, 1996-2001[edit]

Sheikh Hasina formed what she called a "Government of National Consensus" in June 1996, which included one minister from the Jatiya Party and another from the Jatiyo Samajtantric Dal, a very small leftist party. The Jatiya Party never entered into a formal coalition arrangement, and party president H.M. Ershad withdrew his support from the government in September 1997. Only three parties had more than 10 members elected to the 1996 Parliament: The Awami League, BNP, and Jatiya Party. Jatiya Party president, Ershad, was released from prison on bail in January 1997.

Although international and domestic election observers found the June 1996 election free and fair, the BNP protested alleged vote rigging by the Awami League. Ultimately, however, the BNP party decided to join the new Parliament. The BNP soon charged that police and Awami League activists were engaged in large-scale harassment and jailing of opposition activists. At the end of 1996, the BNP staged a parliamentary walkout over this and other grievances but returned in January 1997 under a four-point agreement with the ruling party. The BNP asserted that this agreement was never implemented and later staged another walkout in August 1997. The BNP returned to Parliament under another agreement in March 1998.

In June 1999, the BNP and other opposition parties again began to abstain from attending Parliament. Opposition parties staged an increasing number of nationwide general strikes, rising from 6 days of general strikes in 1997 to 27 days in 1999. A four-party opposition alliance formed at the beginning of 1999 announced that it would boycott parliamentary by-elections and local government elections unless the government took steps demanded by the opposition to ensure electoral fairness. The government did not take these steps, and the opposition subsequently boycotted all elections, including municipal council elections in February 1999, several parliamentary by-elections, and the Chittagong city corporation elections in January 2000.

In July 2001, the Awami League government stepped down to allow a caretaker government to preside over parliamentary elections. Political violence that had increased during the Awami League government's tenure continued to increase through the summer in the run up to the election. In August, Khaleda Zia and Sheikh Hasina agreed during a visit of former President Jimmy Carter to respect the results of the election, join Parliament win or lose, foreswear the use of hartals (violently enforced strikes) as political tools, and if successful in forming a government allow for a more meaningful role for the opposition in Parliament. The caretaker government was successful in containing the violence, which allowed a parliamentary general election to be successfully held on October 1, 2001.

Khaleda Zia, 2001-2006[edit]

The four-party alliance led by the BNP won over a two-thirds majority in Parliament. Begum Khaleda Zia was sworn in on October 10, 2001, as Prime Minister for the third time (first in 1991, second after the February 15, 1996 elections).

Despite her August 2001 pledge and all election monitoring groups declaring the election free and fair, Sheikh Hasina condemned the election, rejected the results, and boycotted Parliament. In 2002, however, she led her party legislators back to Parliament, but the Awami League again walked out in June 2003 to protest derogatory remarks about Hasina by a State Minister and the allegedly partisan role of the Parliamentary Speaker. In June 2004, the AL returned to Parliament without having any of their demands met for an apology to Sheikh Hasina and guarantees of a neutral Speaker. They then attended Parliament irregularly before announcing a boycott of the entire June 2005 budget session.

On August 17, 2005, near-synchronized blasts of improvised explosive devices in 63 out of 64 administrative districts targeted mainly government buildings and killed two persons. An extremist Islamist outfit named Jamiatul Mujahideen, Bangladesh (JMB) claimed responsibility for the blasts aimed to press home their demand for replacement of the secular legal system with Islamic sharia courts. Subsequent attacks on the courts in several districts killed 28 people, including judges, lawyers, and police personnel guarding the courts. A government campaign against the Islamic extremists led to the arrest of hundreds of senior and mid-level JMB leaders. Six top JMB leaders were tried and sentenced to death for their role in the murder of two judges; another leader was tried and sentenced to death in absentia in the same case.

In February 2006, the AL returned to Parliament, raised demands for early elections, and requested significant changes in the electoral and caretaker government systems to stop alleged moves by the ruling coalition to rig the next election. The AL blames the ruling party for several high-profile attacks on opposition leaders, and asserts that the ruling party is bent on eliminating Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League as a viable force. The BNP and its allies accuse the AL of maligning Bangladesh at home and abroad out of jealousy over the government's performance on development and economic issues. Dialogue between the Secretaries General of the main ruling and opposition parties failed to sort out the electoral reform issues.

Caretaker Government, October 2006-Present[edit]

The 13th Amendment to the constitution required the president to offer the position of the Chief Adviser to the immediate past Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, Justice K.M. Hasan, once the previous parliamentary session expired on October 28, 2006. The AL opposed Justice Hasan, alleging that he belonged to ruling BNP in his past life and that the BNP government in 2004 amended the constitution to extend retirement age for the Supreme Court judges to make sure that Justice Hasan became the Chief Adviser during the next elections to help BNP win the election. Justice Hasan declined the position, and after two days of violent protests, President Iajuddin Ahmed also assumed the role of Chief Adviser to the caretaker government.

On January 3, 2007, the Awami League announced that they would boycott the January 22 parliamentary elections. The Awami League planned a series of country-wide general strikes and transportation blockades.

On January 11, 2007, President Iajuddin Ahmed declared a state of emergency under the Bangladesh constitution, resigned as Chief Adviser, and indefinitely postponed parliamentary elections. On January 12, former Bangladesh Bank governor Fakhruddin Ahmed was sworn in as the new Chief Adviser, and ten new advisers (ministers) have been appointed. Under emergency provisions, the government suspended certain fundamental rights of the citizens as guaranteed by the constitution and detained a large number of politicians and others on apparent suspicion of involvement in corruption and other crimes. The government has announced elections will occur in late 2008.

References[edit]

- ↑ CWA Urges Bangladesh to Release Trafficking Diplomat From House Arrest, Concerned Women for America Press Release, 6/7/2007.

| Copyright Details | |

| License: | This work is in the public domain in the United States because it is a work of the United States Federal Government under the terms of Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 105 of the US Code. |

| Source: | [6] |

| This image may not be freely used on user pages. | |

| If you think this image is incorrectly licensed you may discuss this on the image's talk page. | |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Categories: [Muslim-Majority Countries] [Indian History]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/26/2023 08:53:37 | 292 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Bangladesh | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF