Fallacy Of Extrapolation

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia Alternative names: Hasty Generalization, Hasty Conclusion, Overgeneralization or Unwarranted Extrapolation, Free Extrapolation.

The fallacy of extrapolation (more precisely: fallacy of unwarranted extrapolation), occurs when a phenomenon responsible for a number of trivial local effects is read into the great global phenomena, or when a generalized rule is concluded based on too few cases.[1] For example, Darwin's theory of evolution makes use of a fantastic extrapolation in which the mechanisms of random variation and natural selection are declared to account for the development of such complex structures as the mammalian eye or the immuno-defense system.[2] When attempting for an interpretation of research results, the scientist must be leery of extrapolating beyond the range of the data and conscious of the underlying assumptions to avoid drawing invalid conclusions.[3]

Contents

Valid vs. Fallacious Extrapolations[edit]

In general, extrapolation is a legitimate scientific tool. There are at least two aspects that help to distinguish between valid and fallacious extrapolation:[1]

- The likelihood of erroneous extrapolation is higher when insufficient data points were obtained for its construction.

- In science, the research is used to confirm or disprove the predictions of hypothesis. Reporting an extrapolation before testing it is unwise.

Typical examples[edit]

Euler's conjecture[edit]

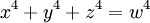

Based on evidence from unsuccessful manual searches of relatively few numbers, Euler predicted that there were no whole number solutions to the following equation, similar to one pertaining to famous Fermat's Last Theorem:

For two hundred years nobody could disprove this claim despite years of computer sifting. Lack of a counter-example was interpreted as strong evidence in favor of a theory until Naom Elkies of Harvard University discovered the solution in 1988.[4] Despite all the evidence, Euler's conjecture turned out to be false at the end. Extrapolating a theory to cover an infinity of numbers based on insufficient and limited amount of evidence without absolute proof has shown to be an unacceptable gamble. The moral is that it is not possible to use evidence from first local set of million numbers to prove the theory or rather conjecture about global set of all numbers.[5]

Microevolution and Macroevolution[edit]

In the 1980 University of Chicago conference entitled "Evolution", scientists were trying to address the question whether the mechanisms underlying microevolution can be extrapolated to explain the phenomena of macroevolution. Despite the risk of doing violence to the positions of some of the people at the meeting, the answer given was a clear "No".[6]

Hubble constant[edit]

It has been claimed with respect to so called Hubble Law, not without the sense of humor, that “Some people think that Hubble is famous because here was a bunch of coffee stains at piece of graph paper and he was able to draw a straight line through it”.[7] Although Hubble hastily concluded, based on only 20 galaxies, that the redshift of the galaxies appears to be a linear function of their distance, there is also a disturbing evidence that this linear relationship does not describe the facts entirely. Several authors made a point that Hubble's observations suggested a quadratic rather than linear relation. After research of quasars, it has been discovered that if one trends apparent brightness against the redshifts as for galaxies, the result is unexpected diagram with scattered points instead of smooth curve as it is the case of galaxies. This seems to indicate that the quasars do not follow the Hubble Law as do the most other objects. According to other authors including Capria, the value of Hubble constant depends on the cosmological model, and J.Hartnett claims that the Hubble constant is not truly constant but it has shown up that there is an inherent scale dependence to its value. Consequently, new theories emerged such as M.Carmeli's theory of Cosmological special relativity where the Hubble law is rewritten in a new invariant way.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Henry A. Virkler (2005). "9", A Christian's Guide to Critical Thinking. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 224–225. ISBN 1-59752-661-4. Retrieved on 5 July 2015.

- ↑ David Berlinski (2009). "Has Darwin met his match?", The Deniable Darwin. Seattle, USA: Discovery Institute Press (reprinted from Commentary February 1998 by permission), 307. ISBN 978-0-9790141-2-3.

- ↑ Riegelman R. (September 1979). The fallacy of free extrapolation 189–91, 194. Postgraduate medicine. Retrieved on October 31, 2013.

- ↑ David Searle (2009). The True Marvel of Numbers: And How Fermat Proved His Last Theorem!. AuthorHouse, 71. ISBN 978-1-4389-4530-9.

- ↑ Simon Singh (1997). Fermat's Last Theorem. Fourth Estate, 177–178. ISBN 1-85702-521-0.

- ↑ Evolutionary theory under fire: A historic conference in Chicago challenges the four-decade long dominance of the Modern Synthesis 883–887. Science (November 21, 1980). DOI:10.1126/science.610799. “The central question of the Chicago conference was whether the mechanisms underlying microevolution can be extrapolated to explain the phenomena of macroevolution. At the risk of doing violence to the positions of some of the people at the meeting, the answer can be given as a clear, No.”

- ↑ Michail S. Turner. Dark Matter, Dark Energy and Inflation: The Big Mysteries of Cosmology 0h:05min:00sec/1h:11min:39sec. Arizona connection, Lectures series. Retrieved on 2012-10-14. “He also discovered that the universe is expanding. ... Some people think that Hubble is famous because here was a bunch of coffee stains at piece of graph paper and he was able to draw a straight line through it.”

Categories: [Logical Fallacies] [Methodology of Science] [Rhetoric]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/20/2023 18:58:17 | 5 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Fallacy_of_extrapolation | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF