Hovercraft

From Nwe

From Nwe A hovercraft, or air-cushion vehicle (ACV), is a vehicle or craft that can be supported by a cushion of air ejected downwards against a surface close below it, and can in principle travel over any relatively smooth surface. The Hovercraft is designed for traveling over land or water on a supportive cushion of slowly moving, low-pressure air.

History

The first hovercraft was invented and patented by the English inventor Christopher Cockerell, in 1952. Several inventors prior to that date had built or attempted to build vehicles based on the "ground effect" principle (the idea that trapping air between a fast moving vehicle and the ground can give extra lift and reduce drag), but these efforts were of limited success and did not use the annular air cushion that known today

In the mid-1870s, the British engineer Sir John Isaac Thornycroft built a number of ground effect machine test models based on his idea of using air between the hull of a boat and the water to reduce drag. Although he filed a number of patents involving air-lubricated hulls in 1877, no practical applications were found. Over the years, various other people had tried various methods of using air to reduce the drag on ships.

Finnish engineer DI Toivo J. Kaario, head inspector of Valtion Lentokonetehdas (VL) airplane engine workshop, began to design an air cushion craft in 1931. He constructed and tested his craft, dubbed pintaliitäjä ("surface glider"), and received its Finnish patents 18630 and 26122. Kaario is considered to have designed and built the first functional ground effect vehicle, but his invention did not receive sufficient funds for further development.

In the mid 1930s, Soviet engineer Vladimir Levkov assembled about 20 experimental air-cushion boats (fast attack craft and high-speed torpedo boats). The first prototype, designated L-1, had a very simple design, which consisted of two small wooden catamarans that were powered by three engines. Two M-11 radial aero-engines were installed horizontally in the funnel-shaped wells on the platform which connected the catamaran hulls together. The third engine, also an air-cooled M-11, was placed in the aft part of the craft on a removable four-strut pylon. An air cushion was produced by the horizontally-placed engines. During successful tests, one of Levkov's air-cushion craft, called fast attack L-5 boat, achieved a speed of 70 knots, or about 130 kilometers per hour.

In the U.S., during the Second World War, Charles J. Fletcher designed his "Glidemobile" while a United States Navy Reservist. The design worked on the principle of trapping a constant airflow against a uniform surface (either the ground or water), providing anywhere from ten inches to two feet of lift to free it from the surface, and control of the craft would be achieved by the measured release of air. Shortly after being tested on Beezer's Pond in Fletcher's home town of Sparta Township, New Jersey, the design was immediately appropriated by the United States Department of War and classified, denying Fletcher the opportunity to patent his creation. As such, Fletcher's work was largely unknown until a case was brought (British Hovercraft Ltd v. The United States of America) in which the British corporation maintained that its rights, coming from Sir Christopher Cockerell's patent, had been infringed. British Hovercraft's claim, seeking $104,000,000 in damages, was unsuccessful. However, Colonel Melville W. Beardsley (1913-1998), an American inventor and aeronautical engineer, received $80,000 from Cockerell for his rights to American patents. Beardsley worked on a number of unique ideas in the 1950s and '60s which he patented. His company built craft based on his designs at his Maryland base for the U.S. Government and commercial applications. Beardsley later worked for the U.S. Navy on developing the Hovercraft further for military use. Dr. W. Bertelsen also worked on developing early ACVs in the U.S. Dr. Bertelsen built an early prototype of a hovercraft vehicle in 1959 (called Aeromobile 35-B), and was photographed for Popular Science magazine riding the vehicle over land and water in April 1959. The article on his invention was the front page story for the July 1959, edition of Popular Science.

In 1952, the British inventor Christopher Cockerell worked with air lubrication with test craft on the Norfolk Broads. From this, he moved on to the idea of a deeper air cushion. Cockerell used simple experiments involving a vacuum cleaner motor and two cylindrical cans to create his unique peripheral jet system, the key to his hovercraft invention, patented as the "hovercraft principle." He proved the workable principle of a vehicle suspended on a cushion of air blown out under pressure, making the vehicle easily mobile over most surfaces. The supporting air cushion would enable it to operate over soft mud, water, and marshes and swamps as well as on firm ground. He designed a working model vehicle based on his patent. Showing his model to the authorities led to it being put on the secret list as being of possible military use and therefore restricted. However, to keep Britain in the lead in developments, in 1958, the National Research and Development Corporation took on his design (paying £1000 for the rights) and paid for an experimental vehicle to be built by Saunders-Roe, the SR.N1. The craft was built to Cockerell's design and was launched in 1959, and made a crossing from France to the UK on the 50th anniversary of Bleriot's cross-Channel flight. He was knighted for his services to engineering in 1969. Sir Christopher coined the word "Hovercraft" to describe his invention.

Design

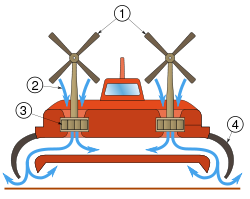

Hovercraft have one or more separate engines (some craft, such as the SR-N6, have one engine with a drive split through a gearbox). One engine drives the fan (the impeller) which is responsible for lifting the vehicle by forcing air under the craft. The air therefore must exit throughout the "skirt," lifting the craft above the area on which the craft resides. One or more additional engines are used to provide thrust in order to propel the craft in the desired direction. Some hovercraft utilize ducting to allow one engine to perform both tasks, by directing some of the air to the skirt, the rest of the air passing out of the back to push the craft forward.

Civil commercial hovercraft

The British aircraft manufacturer Saunders Roe, which had aeronautical expertise, developed the first practical man-carrying hovercraft, the SR-N1, which carried out several test programmes in 1959 to 1961 (the first public demonstration in 1959), including a cross-channel test run. The SR-N1 was powered by one (piston) engine, driven by expelled air. Demonstrated at the Farnborough Airshow in 1960, it was shown that this simple craft could carry a load of up to 12 marines with their equipment as well as the pilot and co-pilot with only a slight reduction in hover height proportional to the load carried. The SR.N1 did not have any skirt, instead using the peripheral air principle that Sir Christopher has patented. It was later found that the craft's hover height was improved by the addition of a "skirt" of flexible fabric or rubber around the hovering surface to contain the air. The skirt was an independent invention made by a Royal Navy officer, Latimer-Needham, who sold his idea to Westland (parent company of Saunders-Roe), and who worked with Sir Christopher to develop the idea further.

The first passenger-carrying hovercraft to enter service was the Vickers VA-3, which in the summer of 1962, carried passengers regularly along the North Wales Coast from Moreton, Merseyside, to Rhyl. It was powered by two turboprop aero-engines and driven by propellers.

During the 1960s Saunders Roe developed several larger designs which could carry passengers, including the SR-N2, which operated across the Solent in 1962, and later the SR-N6, which operated across the Solent from Southsea to Ryde on the Isle of Wight, for many years. Operations by Hovertravel commenced on July 24, 1965, using the SR-N6, which carried just 38 passengers. Two modern 98 seat AP1-88 hovercraft now ply this route, and over 20 million passengers have used the service as of 2004.

In 1966, two Cross Channel passenger hovercraft services were inaugurated using hovercraft. Hoverlloyd ran services from Ramsgate Harbour to Calais and Townshend Ferries also started a service to Calais from Dover.

As well as Saunders Roe and Vickers (which combined in 1966, to form the British Hovercraft Corporation), other commercial craft were developed during the 1960s, in the United Kingdom, by Cushioncraft (part of the Britten-Norman Group) and Hovermarine (the latter being "sidewall" type hovercraft, where the sides of the hull projected down into the water to trap the cushion of air with "normal" hovercraft skirts at the bow and stern).

The world's first car-carrying hovercraft made their debut in 1968; the BHC Mountbatten class (SR-N4) models, each powered by four Rolls-Royce Proteus gas turbine engines, were used to start the regular car and passenger ferry service across the English Channel from Dover, Ramsgate, where a special hoverport had been built at Pegwell Bay by Hoverlloyd, and Folkestone in England to Calais and Boulogne in France. The first SR-N4 had a capacity of 254 passengers and 30 cars, and a top speed of 83 knots (96 miles per hour). The Channel crossing took around 30 minutes and was run rather like an airline with flight numbers. The later SR-N4 MkIII had a capacity of 418 passengers and 60 cars. The French-built SEDAM N500 Naviplane had a capacity of 385 passengers and 45 cars,[1] of which only one example entered service, and was used intermittently for a few years on the cross-channel service due to technical problems. The service ceased in 2000, after 32 years, due to competition with traditional ferries, catamaran, and the opening of the Channel tunnel.

In 1998, the U.S. Postal Service began using the British built Hoverwork AP.1-88 to haul mail, freight, and passengers from Bethel, Alaska, to and from eight small villages along the Kuskokwim River. Bethel is far removed from the Alaska road system, thus making the hovercraft an attractive alternative to the air based delivery methods used prior to introduction of the hovercraft service. Hovercraft service is suspended for several weeks each year while the river is beginning to freeze, to minimize damage to the river ice surface. The hovercraft is perfectly able to operate during the freeze-up period; however, this could potentially break the ice and create hazards for villagers using their snowmobiles along the river during the early winter.

The commercial success of hovercraft suffered from rapid rises in fuel prices during the late 1960s and 1970s following conflict in the Middle East. Alternative over-water vehicles, such as wave-piercing catamarans (marketed as the SeaCat in Britain) use less fuel and can perform most of the hovercraft's marine tasks. Although developed elsewhere in the world for both civil and military purposes, except for the Solent Ryde to Southsea crossing, hovercraft disappeared from the coastline of Britain until a range of Griffon Hovercraft were bought by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution.

In Finland, small hovercraft are widely used in maritime rescue and during the rasputitsa ("mud season") as archipelago liaison vehicles.

The Scandinavian airline SAS used to charter an AP. 1-88 Hovercraft for regular passengers between Copenhagen Airport, Denmark, and the SAS Hovercraft Terminal in Malmo, Sweden.

Military hovercraft

First applications of the hovercraft in military use was with the SR.N1 through SR.N6 craft built by Saunder Roe in the Isle of Wight in the UK, and used by the UK joint forces. To test the use of the hovercraft in military applications, the UK set up the Interservice Hovercraft Trails Unit (IHTU) base at Lee-on-the-Solent, in the UK (now the site of the Hovercraft Museum). This unit carried out trials on the SR.N1 from Mk1 through Mk5 as well as testing the SR.N2, 3, 5 and 6 craft. Currently, the Royal Marines use the Griffon 2000TDX as an operational craft. This craft was recently deployed by the UK in Iraq.

In the U.S., during the 1960s, Bell licensed and sold the Saunder Roe SRN-5 as the Bell SK-5. They were deployed on trial to the Vietnam War by the Navy as PACV patrol craft in the Mekong Delta where their mobility and speed was unique. This was used in both the UK SR.N5 curved deck configuration and later with modified flat deck, gun turret, and grenade launcher, designated the 9255 PACV. One of these craft is currently on display in the Army Transport Museum in Virginia. Experience led to the proposed Bell SK-10, which was the basis for the LCAC now deployed.

The former Soviet Union was one of the first few nations to use a hovercraft, the Bora, as a guided missile corvette.

The Finnish Navy designed an experimental missile attack hovercraft class, Tuuli class hovercraft, in the late 1990s. The prototype of the class, Tuuli, was commissioned in 2000. It proved an extremely successful design for a littoral fast attack craft, but due to fiscal reasons and doctrinal change in the Navy, the hovercraft was soon withdrawn.

The Hellenic Navy has bought four Russian designed Zubr/Pomornik (LCAC). This is the world’s largest military Landing air-cushion craft.

Hoverbarge

A real benefit of air cushion vehicles in moving heavy loads over difficult terrain, such as swamps, was overlooked by the excitement of the government funding to develop high-speed hovercraft. It was not until the early 1970s, that the technology was used for moving a modular marine barge with a dragline on board for use over soft reclaimed land.

Mackace (Mackley Air Cushion Equipment) produced a number of successful Hoverbarges, such as the 250 ton payload Sea Pearl, which operated in Abu Dhabi, and the twin 160 ton payload Yukon Princesses, which ferried trucks across the Yukon river to aid the pipeline build. Hoverbarges are still in operation today. In 2006, Hovertrans (formed by the original managers of Mackace) launched a 330 ton payload drilling barge in the swamps of Suriname.

The Hoverbarge technology is somewhat different than high-speed hovercraft, which has traditionally been constructed using aircraft technology. The initial concept of the air cushion barge has always been to provide a low-tech amphibious solution for accessing construction sites using typical equipment found in this area, such as diesel engines, ventilating fans, winches, and marine equipment. The load to move a 200-ton payload ACV barge at 5 knots would only be 5 tons. The skirt and air distribution design on the high-speed craft, again, is more complex, as they have to cope with the air cushion being washed out by a wave and wave impact. The slow speed and large mono chamber of the hover barge actually helps reduce the effect of wave action, giving a very smooth ride.

Hovertrain

Several attempts have been made to adopt air cushion technology for use in fixed track systems, in order to take advantage of the lower frictional forces to deliver high speeds. The most advanced example of this was the Aérotrain, an experimental high speed hovertrain built and operated in France between 1965 and 1977. The project was abandoned in 1977, due to lack of funding, the death of its main protagonist, and the adoption of TGV by the French government as its high-speed ground transport solution.

At the other end of the speed spectrum, the Dorfbahn Serfaus has been in continuous operation since 1985. This is an unusual underground air cushion funicular rapid transit system, situated in the Austrian ski resort of Serfaus. Only 1,280 m (4,199.5 ft) long, the line reaches a maximum speed of Template:Mph.

Records

- World's Largest Civil Hovercraft—The BHC SRN4 Mk III at 56.4 m (185 ft) length and 310 metric tons (305 tons) weight, can accommodate 418 passengers and 60 cars.

- English Channel crossing—22 minutes by Princess Anne MCH SR-N4 Mk3 on September 14, 1995

- World's Hovercraft Speed Record[2]—September 18, 1995—Speed Trials, Bob Windt (U.S.) 137.4 kilometers per hour (kmph). (85.87mph), 34.06 secs measured kilometer

Hobbyists

There are an increasing number of small, homebuilt and kit-built hovercraft used for fun and racing purposes, mainly on inland lakes and rivers but also in marshy areas and in some estuaries.

Notes

- ↑ Hoverline Scandinavia, In 1965 Sweden become the pioneers of commercial hovercraft services. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ↑ Hovercraft Club of Great Britain, [http://www.hovercraft.org.uk/download/hovercraftspeedrecords.doc Hovercraft speed records.] Retrieved April 24, 2007. }}

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bullard, Lisa. 2007. Hovercraft (Pull Ahead Books). North Minneapolis: First Avenue Editions. ISBN 0822564270

- Hopping, Lorraine Jean. 2004. Flight Test Lab: Hovercrafts: Build and Launch 4 Different Hovercrafts! Berkeley, CA: Silver Dolphin Books. ISBN 1592230318

- Jackson, Kevin. 2004. Discover the Hovercraft. Windermere, FL: Flexitech LLC. ISBN 0975341405

External links

All links retrieved January 15, 2018.

- Hovercraft on the Isle of Wight, UK from H2G2.

- Personal website for Hovercraft Builders.

- Rescue hovercraft in Burnham-On-Sea, Somerset, UK.

- The Hovercraft Museum.

- English hovercraft of the 1960s.

- ABS Hovercraft, a major hovercraft designer/manufacturer.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:49:07 | 38 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Hovercraft | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF