Charles Lindbergh

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974) was an aviation pioneer and the world's most famous hero in the 1920s. In 1927 he became the first to fly alone, non-stop, from New York to Paris. This solo feat created a sensation and he was welcomed by enormous crowds in France and, on his return, in New York. He was a hero to conservatives for his exploits and his leadership of the "isolationists" in opposition to Franklin D. Roosevelt's foreign policy in the late 1930s.

Contents

The flight[edit]

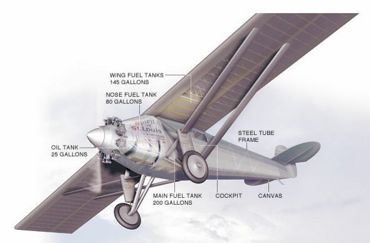

Lindbergh was bold in using a single-engine plane and in flying solo. He argued that aircraft engines were now reliable enough to be counted on, and that the loss of a single engine in a multi-engine aircraft would be so serious that having several engines increased, rather than reduced, the risk. Bolder still was his decision to fly alone, meaning that he needed to remain awake for 33 hours.

Celebrity[edit]

Myron T. Herrick, US ambassador to France, used Charles Lindbergh's solo flight across the Atlantic in 1927 to improve relations between the United States and France. Rescuing him from the crowd at Le Bourget airport, Herrick sheltered Lindbergh, gave him a "crash course in modesty," and presented him to the world in a manner designed to make the best use of his hero status to build good relations between the two nations. To a significant degree, Herrick helped make Lindbergh into an American icon with lasting fame.

Writers were mesmerized by the flight. Over 10,000 poems about it appeared in local newspapers. Across the globe people projected on the flight their own emotions, which typically involved two themes. Looking to the past. the achievement was a brief escape from the course of history, an emergence into a new and open world with the self-sufficient individual at its center. Looking to the future the flight represented a new and higher stage in historical evolution and that its fulfillment lay in the development of society. For some Americans, the American ideal was an escape from institutions, from the forms of society, and from limitations put upon the free individual; for others, the American ideal was the elaboration of the complex institutions which made modern society possible, an acceptance of the discipline of the machine, and the achievement of the individual within a context of which he was only a part. The two views were contradictory but both can be seen in the public reaction to Lindbergh's flight.[1]

Lindbergh's years in the public spotlight illustrate the power of the press to shape images of celebrities to suit its own agendas. Between 1927 and the late 1930s, the mainstream media depicted Lindbergh as rising above the hazards of celebrity. Lindbergh's rude behavior in front of crowds and even in dealing with the press was dismissed as a need for privacy. This image reflected the middle-class ideal of true success. Tabloids pioneered an alternative version of Lindbergh as a boorish, ungrateful cad. The dominant media adopted this critical image after Lindbergh returned to the United States and advocated isolationism at a time when the dominant media supported Roosevelt's interventionism. Lindbergh had become a pariah, but his ideas had not changed since the 1920s. What had changed was his usefulness to the media.[2]

He was known as "Lucky Lindy" and inspired a dance, the "Lindy Hop."

Family life vs. fame[edit]

In 1929 Lindbergh married Anne Morrow (1906-2001), daughter of a wealthy diplomat. She became a famous author in her own right. Anne Morrow Lindbergh became a popular poet and writer. In her best-seller North to the Orient (1935), she narrates the 1931 pioneering flight she and Charles made from New York over Canada and across the Arctic to Japan and China.

She desired a degree of privacy impossible to find. The more the couple tried to avoid reporters, the more they were hounded.[3]

They had six children.

Son murdered[edit]

In 1932 their first son was kidnapped for ransom, but died when the kidnapper's ladder broke. Bruno Richard Hauptmann was executed for the crime. The crime and investigation dominated national attention for years. The Lindberghs left the country and settled in France, returning when World War II broke out. In his later years, Lindbergh lived quietly in Hana, Hawaii where he died of cancer August 26, 1974.

Germany[edit]

Lindbergh visited Germany in 1938 on a mission for the U.S. Air Corps. he studied and was impressed by the "Luftwaffe", the German air force, warning Americans it had the best equipment in the world. He accepted a medal from Hermann Goering for his services to aviation. Roosevelt supporters vehemently denounced him as a Nazi sympathizer, a charge he strongly denied and which historians generally reject.America First[edit]

Lindbergh was the leading isolationist of the day, and the hero to conservatives opposing Roosvelt's foreign policies. He strongly opposing American entry into World War II as an unnecessary war that would help Britain and the Jews, but not serve American interests and would lead to a dictatorship at home. He made a major speech on 11 September 1941 at an America First rally in Des Moines, Iowa, that led ex-New York governor and presidential candidate Al Smith to charge Lindbergh with being an anti-Semite. Previous speeches had hinted at Jewish control of the government, but it was in this speech that Lindbergh named Jews as a group of "war agitators."

World War II[edit]

Lindbergh was an outspoken opponent of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who used the Internal Revenue Service and the FBI to spy on him, and refused to allow him to play any role in the war.[4]

Nevertheless, Lindbergh worked as a civilian consultant to aviation companies during the war and even flew combat missions. He worked for Pan American Airways (Pan Am), scouting possible routes all over the world that Pan American could fly. In later years, he served on the Board of Directors of the Lockheed Corporation.

Lindbergh wrote two books about his flight: We and The Spirit of St. Louis.

Environment[edit]

Lindbergh strongly promoted aviation, but came to question the peaceful uses of aviation after viewing Germany's Luftwaffe in 1936. After World War II Lindbergh again visited Germany and saw the destruction caused by Allied bombing, which he blamed on the Germans' obsession with science and technology. Lindbergh's world had been one in which technology was equated with progress, but he slowly realized that technological progress did not necessarily mean social progress. He lent his name to numerous environmental causes, particularly wildlife protection. He consulted throughout his life on aircraft development, including the Supersonic Transport program (SST), but with increasing ambivalence. His ultimate opposition to the SST became a deciding factor in defeating its development in the United States.[5]

See also[edit]

Further reading[edit]

- Berg, A. Scott. Lindbergh (1999), the best biography excerpt and text search

- Cole, Wayne S. Charles A. Lindbergh and the Battle Against American Intervention in World War II (1974) 298pp

- Milton, Joyce. Loss of Eden: A Biography of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh. (1993). 520 pp.

- Mosely, Leonard. Lindbergh: A Biography (2000) excerpt and text search

- Ward, John William. "The Meaning of Lindbergh's Flight," American Quarterly 10, no. 1 (Spring 1958) pp 3–16 online

- "Charles Lindbergh, An American Aviator" Spirit of St. Louis 2 Project

Video[edit]

- "Lindbergh". produced by Stephen Ives; 58min. Insignia Films, 1990. Distributed by PBS Video,

Notes[edit]

- ↑ Ward (1958)

- ↑ Charles L. Ponce De Leon, "The Man Nobody Knows: Charles A. Lindbergh and the Culture of Celebrity." Prospects 1996 21: 347-372.

- ↑ Sacred Marriage, Pp. 136-142

- ↑ Douglas M. Charles, “ Informing FDR: FBI Political Surveillance and the Isolationist-Interventionist Foreign Policy Debate, 1939-1945.” Diplomatic History 2000 24(2): 211-232; Douglas M. Charles, and John P. Rossi, "FBI Political Surveillance and the Charles Lindbergh Investigation, 1939-1944", Historian 1997 59(4): 831-847

- ↑ Leonard S. Reich, "From The Spirit of St. Louis to the SST: Charles Lindbergh, Technology, and Environment." Technology and Culture 1995 36(2): 351-393.

Categories: [Pilots] [United States History] [1920s] [New Deal] [Conservatives] [Environmentalism] [Anti-Semitism] [Non-Interventionism]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/13/2023 04:16:25 | 35 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Charles_Lindbergh | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF