Fourteen Points

From Conservapedia

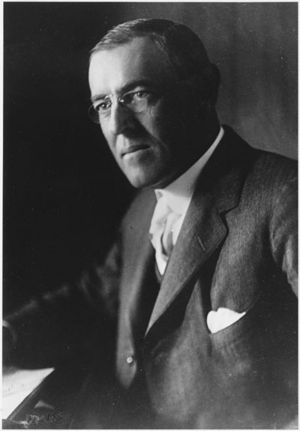

From Conservapedia The Fourteen Points was a major policy position by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, expressed in a speech to Congress on January 8, 1918. It was a peace plan designed to rally opponents of the war in Germany, and it succeeded in that main goal. Points 4-14 were largely realized in fact by 1922. Parts of the first three points were adopted in the long run, and even in the 21st century are a basis of world diplomacy.

The plan expressed of Wilsonian idealism in foreign policy, that is, "Wilsonianism." The goal was to identify the main underlying causes of war in the entire world, and to eliminate or minimize them. The first five points were broad in scope: open diplomacy; freedom of the seas; the beating down of economic barriers; the reduction of armament; and the adjustment of colonial claims on a fair basis. There followed Wilson's formulas for applying justice to specific countries or areas. The 14th point was a declaration in favor of an Association of Nations (or League of Nations) to resolve unexpected future conflicts and thus guarantee world peace. In three followup addresses, Wilson set forth elaborations, clarifications and new point, bringing the total proposals to twenty-three.[1]

Wilson sought a just and lasting peace; no bartering of ethnic groups; the satisfaction of legitimate national aspirations; honorable international dealing; the destruction of arbitrary militarism; and territorial adjustments in the interests of the peoples concerned, or "self determination." He was vague on the rights of minority groups in areas where self-determination would be controlled by ethnic majorities.

Wilson was most of all committed to a League of Nations, a peace agency that would be able to use force to preserve territorial integrity and political independence among large and small nations alike. The speech was highly idealistic, translating Wilson's progressive ideals of democracy, self-determination, open agreements, and free trade into the international realm. Much of the speech was drafted by aide Walter Lippmann. It made several suggestions for specific disputes in Europe on the recommendation of Wilson's foreign policy advisor, Colonel House, and his team of 150 advisors known as “The Inquiry.” Politically, he made a serious blunder by not seeking advice from Republican leaders in his policy formulation; some of them, such as William Howard Taft, had very similar goals in mind and could have forestalled the partisanship that caused Wilson trouble in 1919 and led to American refusal to join the league,

Wilson did not invent new terms; he pulled together the best of existing war aims, including many that had been expressed by the British and a few that originated with the Germans and the Bolsheviks, and then added a few of his own. Walter Lippmann helped draft the speech. Wilson's timing was brilliant; it was the combination that was so powerful: here was an authoritative voice, unburdened by any treaty, who proclaimed what many saw as the best possible outcome of the war, and one that would justify the horrible events by cleansing the earth and opening up a peaceful utopia. Europe went wild when he arrived in Paris, for Wilson had made himself the most trusted man in the world.

The promise of national self-determination aroused audiences in Ireland, Eastern and Central Europe, Asia and the Middle East, and remains a powerful idea in the 21st century.

Contents

Contents[edit]

In summary the points are:

I. Abolition of secret treaties

II. Freedom of the seas

III. Free Trade

IV. Disarmament

V. Adjustment of colonial claims (decolonization and national self-determination)

VI. Russia to be assured independent development and international withdrawal from occupied Russian territory

VII. Restoration of Belgium to antebellum national status

VIII. Alsace-Lorraine returned to France from Germany

IX. Italian borders redrawn on lines of nationality

X. Autonomous development of Austria-Hungary as a nation, as the Austro-Hungarian Empire dissolved

XI. Romania, Serbia, Montenegro, and other Balkan states to be granted integrity, have their territories deoccupied, and Serbia to be given access to the Adriatic Sea

XII. Sovereignty for the Turkish people of the Ottoman Empire as the Empire dissolved, autonomous development for other nationalities within the former Empire

XIII. Establishment of an independent Poland with access to the sea

XIV. General association of the nations – a multilateral international association of nations to enforce the peace (League of Nations)

Background[edit]

The details of Wilson's January 8, 1918, speech were based on reports generated by “The Inquiry,” a group of about 150 political and social scientists organized by Wilson's adviser and long-time friend, Col. Edward M House. Their job was to study Allied and American policy in virtually every region of the globe and analyze economic, social, and political facts likely to come up in discussions during the peace conference. The team began its work in secret and in the end produced and collected nearly 2,000 separate reports and documents plus at least 1,200 maps.

In the speech, Wilson directly addressed what he perceived as the causes for the world war by calling for the abolition of secret treaties, a reduction in armaments, an adjustment in colonial claims in the interests of both native peoples and colonists, and freedom of the seas. Wilson also made proposals that would ensure world peace in the future. For example, he proposed the removal of economic barriers between nations, the promise of “self-determination” for those oppressed minorities, and a world organization that would provide a system of collective security for all nations. Wilson's 14 Points were designed to undermine the Central Powers’ will to continue and to inspire the Allies to victory. The 14 Points were broadcast throughout the world and were showered from rockets and shells behind the enemy's lines.

Paris Peace Conference 1919[edit]

The speech was widely hailed by public opinion in the U.S. and Europe, and drove a wedge between the German leaders and the German people, who welcomed Wilson's formula. The Fourteen Points thus played a major role in Germany's surrender.

The Fourteen Points made Wilson the hero of the world as the victors gathered in Paris to write the terms that were to be imposed upon defeated Germany. Although Wilson in fact gained most of his points, he was dismayed to realize that Britain, France, and Italy wanted revenge and humiliation for Germany. They wanted huge cash reparations so that Germany would pay the entire cost of the war, including veterans' benefits. The French government demanded high reparations from Germany to pay for the past and future costs of the war to France. Britain, as the great naval power, did not want freedom of the seas. Wilson compromised with Georges Clemenceau, Lloyd George, and many other European leaders during the Paris Peace talks to ensure that most of the points, and especially the fourteenth point, the League of Nations, would be established.

League of Nations[edit]

Wilson's capstone point calling for a world organization that would provide some system of collective security was incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles. This organization would later be known as the League of Nations. Though Wilson launched a tireless missionary campaign to overcome opposition in the U.S. Senate to the adoption of the treaty and membership in the League, the treaty was never adopted by the Senate, and the United States never joined the League of Nations. Wilson would later suggest that without American participation in the League, there would be another world war within a generation.

Text of the "Fourteen Points" speech, January 8, 1918[edit]

Gentlemen of the Congress:

Once more, as repeatedly before, the spokesmen of the Central Empires have indicated their desire to discuss the objects of the war and the possible basis of a general peace. Parleys have been in progress at Brest-Litovsk between Russian representatives and representatives of the Central Powers to which the attention of all the belligerents have been invited for the purpose of ascertaining whether it may be possible to extend these parleys into a general conference with regard to terms of peace and settlement.

The Russian representatives presented not only a perfectly definite statement of the principles upon which they would be willing to conclude peace but also an equally definite program of the concrete application of those principles. The representatives of the Central Powers, on their part, presented an outline of settlement which, if much less definite, seemed susceptible of liberal interpretation until their specific program of practical terms was added. That program proposed no concessions at all either to the sovereignty of Russia or to the preferences of the populations with whose fortunes it dealt, but meant, in a word, that the Central Empires were to keep every foot of territory their armed forces had occupied—every province, every city, every point of vantage—as a permanent addition to their territories and their power.

It is a reasonable conjecture that the general principles of settlement which they at first suggested originated with the more liberal statesmen of Germany and Austria, the men who have begun to feel the force of their own people's thought and purpose, while the concrete terms of actual settlement came from the military leaders who have no thought but to keep what they have got. The negotiations have been broken off. The Russian representatives were sincere and in earnest. They cannot entertain such proposals of conquest and domination.

The whole incident is full of significances. It is also full of perplexity. With whom are the Russian representatives dealing? For whom are the representatives of the Central Empires speaking? Are they speaking for the majorities of their respective parliaments or for the minority parties, that military and imperialistic minority which has so far dominated their whole policy and controlled the affairs of Turkey and of the Balkan states which have felt obliged to become their associates in this war?

The Russian representatives have insisted, very justly, very wisely, and in the true spirit of modern democracy, that the conferences they have been holding with the Teutonic and Turkish statesmen should be held within open, not closed, doors, and all the world has been audience, as was desired. To whom have we been listening, then? To those who speak the spirit and intention of the resolutions of the German Reichstag of the 9th of July last, the spirit and intention of the Liberal leaders and parties of Germany, or to those who resist and defy that spirit and intention and insist upon conquest and subjugation? Or are we listening, in fact, to both, unreconciled and in open and hopeless contradiction? These are very serious and pregnant questions. Upon the answer to them depends the peace of the world.

But, whatever the results of the parleys at Brest-Litovsk, whatever the confusions of counsel and of purpose in the utterances of the spokesmen of the Central Empires, they have again attempted to acquaint the world with their objects in the war and have again challenged their adversaries to say what their objects are and what sort of settlement they would deem just and satisfactory. There is no good reason why that challenge should not be responded to, and responded to with the utmost candor. We did not wait for it. Not once, but again and again, we have laid our whole thought and purpose before the world, not in general terms only, but each time with sufficient definition to make it clear what sort of definite terms of settlement must necessarily spring out of them. Within the last week Mr. Lloyd George has spoken with admirable candor and in admirable spirit for the people and Government of Great Britain.

There is no confusion of counsel among the adversaries of the Central Powers, no uncertainty of principle, no vagueness of detail. The only secrecy of counsel, the only lack of fearless frankness, the only failure to make definite statement of the objects of the war, lies with Germany and her allies. The issues of life and death hang upon these definitions. No statesman who has the least conception of his responsibility ought for a moment to permit himself to continue this tragical and appalling outpouring of blood and treasure unless he is sure beyond a peradventure that the objects of the vital sacrifice are part and parcel of the very life of Society and that the people for whom he speaks think them right and imperative as he does.

There is, moreover, a voice calling for these definitions of principle and of purpose which is, it seems to me, more thrilling and more compelling than any of the many moving voices with which the troubled air of the world is filled. It is the voice of the Russian people. They are prostrate and all but hopeless, it would seem, before the grim power of Germany, which has hitherto known no relenting and no pity. Their power, apparently, is shattered. And yet their soul is not subservient. They will not yield either in principle or in action. Their conception of what is right, of what is humane and honorable for them to accept, has been stated with a frankness, a largeness of view, a generosity of spirit, and a universal human sympathy which must challenge the admiration of every friend of mankind; and they have refused to compound their ideals or desert others that they themselves may be safe.

They call to us to say what it is that we desire, in what, if in anything, our purpose and our spirit differ from theirs; and I believe that the people of the United States would wish me to respond, with utter simplicity and frankness. Whether their present leaders believe it or not, it is our heartfelt desire and hope that some way may be opened whereby we may be privileged to assist the people of Russia to attain their utmost hope of liberty and ordered peace.

It will be our wish and purpose that the processes of peace, when they are begun, shall be absolutely open and that they shall involve and permit henceforth no secret understandings of any kind. The day of conquest and aggrandizement is gone by; so is also the day of secret covenants entered into in the interest of particular governments and likely at some unlooked-for moment to upset the peace of the world. It is this happy fact, now clear to the view of every public man whose thoughts do not still linger in an age that is dead and gone, which makes it possible for every nation whose purposes are consistent with justice and the peace of the world to avow nor or at any other time the objects it has in view.

We entered this war because violations of right had occurred which touched us to the quick and made the life of our own people impossible unless they were corrected and the world secure once for all against their recurrence. What we demand in this war, therefore, is nothing peculiar to ourselves. It is that the world be made fit and safe to live in; and particularly that it be made safe for every peace-loving nation which, like our own, wishes to live its own life, determine its own institutions, be assured of justice and fair dealing by the other peoples of the world as against force and selfish aggression. All the peoples of the world are in effect partners in this interest, and for our own part we see very clearly that unless justice be done to others it will not be done to us. The program of the world's peace, therefore, is our program; and that program, the only possible program, as we see it, is this:

- Open covenants of peace must be arrived at, after which there will surely be no private international action or rulings of any kind, but diplomacy shall proceed always frankly and in the public view.

- Absolute freedom of navigation upon the seas, outside territorial waters, alike in peace and in war, except as the seas may be closed in whole or in part by international action for the enforcement of international covenants.

- The removal, so far as possible, of all economic barriers and the establishment of an equality of trade conditions among all the nations consenting to the peace and associating themselves for its maintenance.

- Adequate guarantees given and taken that national armaments will be reduced to the lowest points consistent with domestic safety.

- A free, open-minded, and absolutely impartial adjustment of all colonial claims, based upon a strict observance of the principle that in determining all such questions of sovereignty the interests of the population concerned must have equal weight with the equitable claims of the government whose title is to be determined.

- The evacuation of all Russian territory and such a settlement of all questions affecting Russia as will secure the best and freest cooperation of the other nations of the world in obtaining for her an unhampered and unembarrassed opportunity for the independent determination of her own political development and national policy, and assure her of a sincere welcome into the society of free nations under institutions of her own choosing; and, more than a welcome, assistance also of every kind that she may need and may herself desire. The treatment accorded Russia by her sister nations in the months to come will be the acid test of their good will, of their comprehension of her needs as distinguished from their own interests, and of their intelligent and unselfish sympathy.

- Belgium, the whole world will agree, must be evacuated and restored, without any attempt to limit the sovereignty which she enjoys in common with all other free nations. No other single act will serve as this will serve to restore confidence among the nations in the laws which they have themselves set and determined for the government of their relations with one another. Without this healing act the whole structure and validity of international law is forever impaired.

- All French territory should be freed and the invaded portions restored, and the wrong done to France by Prussia in 1871 in the matter of Alsace-Lorraine, which has unsettled the peace of the world for nearly fifty years, should be righted, in order that peace may once more be made secure in the interest of all.

- A re-adjustment of the frontiers of Italy should be effected along clearly recognizable lines of nationality.

- The peoples of Austria-Hungary, whose place among the nations we wish to see safeguarded and assured, should be accorded the freest opportunity of autonomous development.

- Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro should be evacuated; occupied territories restored; Serbia accorded free and secure access to the sea; and the relations of the several Balkan states to one another determined by friendly counsel along historically established lines of allegiance and nationality; and international guarantees of the political and economic independence and territorial integrity of the several Balkan states should be entered into.

- The Turkish portions of the present Ottoman Empire should be assured a secure sovereignty, but the other nationalities which are now under Turkish rule should be assured an undoubted security of life and an absolutely unmolested opportunity of autonomous development, and the Dardanelles should be permanently opened as a free passage to the ships and commerce of all nations under international guarantees.

- An independent Polish state should be erected which should include the territories inhabited by indisputably Polish populations, which should be assured a free and secure access to the sea, and whose political and economic independence and territorial integrity should be guaranteed by international covenant.

- A general association of nations must be formed under specific covenants for the purpose of affording mutual guarantees of political independence and territorial integrity to great and small states alike.

In regard to these essential rectifications of wrong and assertions of right we feel ourselves to be intimate partners of all the governments and peoples associated together against the Imperialists. We cannot be separated in interest or divided in purpose. We stand together until the end.

For such arrangements and covenants we are willing to fight and to continue to fight until they are achieved; but only because we wish the right to prevail and desire a just and stable peace such as can be secured only by removing the chief provocations to war, which this program does remove. We have no jealousy of German greatness, and there is nothing in this programmer that impairs it. We grudge her no achievement or distinction of learning or of pacific enterprise such as have made her record very bright and very enviable. We do not wish to injure her or to block in any way her legitimate influence or power. We do not wish to fight her either with arms or with hostile arrangements of trade if she is willing to associate herself with us and the other peace- loving nations of the world in covenants of justice and law and fair dealing. We wish her only to accept a place of equality among the peoples of the world, -- the new world in which we now live, -- instead of a place of mastery.

Neither do we presume to suggest to her any alteration or modification of her institutions. But it is necessary, we must frankly say, and necessary as a preliminary to any intelligent dealings with her on our part, that we should know whom her spokesmen speak for when they speak to us, whether for the Reichstag majority or for the military party and the men whose creed is imperial domination.

We have spoken now, surely, in terms too concrete to admit of any further doubt or question. An evident principle runs through the whole program I have outlined. It is the principle of justice to all peoples and nationalities, and their right to live on equal terms of liberty and safety with one another, whether they be strong or weak.

Unless this principle be made its foundation no part of the structure of international justice can stand. The people of the United States could act upon no other principle; and to the vindication of this principle they are ready to devote their lives, their honor, and everything they possess. The moral climax of this the culminating and final war for human liberty has come, and they are ready to put their own strength, their own highest purpose, their own integrity and devotion to the test.

See also[edit]

External links[edit]

- Wilson, Woodrow. President Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points (1918).

- The 14 points

Bibliography[edit]

- Ambrosius, Lloyd E. Wilsonianism: Woodrow Wilson and His Legacy in American Foreign Relations (2002) excerpt and text search

- Bailey, Thomas A. Wilson and the Peacemakers: Combining Woodrow Wilson and the Lost Peace and Woodrow Wilson and the Great Betrayal (1947) online edition

- Clements, Kendrick, A. Woodrow Wilson: World Statesman (1999)

- Clements, Kendrick A. "Woodrow Wilson and World War I," Presidential Studies Quarterly 34:1 (2004). pp 62+. online edition

- Knock, Thomas J. To End All Wars: Woodrow Wilson and the Quest for a New World Order (1995) excerpt and text search

- Link, Arthur S. Wilson the Diplomatist: A Look at His Major Foreign Policies (1957) online edition

- Link, Arthur S. Woodrow Wilson and a Revolutionary World, 1913-1921 (1982) online edition

- Link, Arthur S. Woodrow Wilson: Revolution, War, and Peace (1979) online edition

- Manela, Erez. The Wilsonian Moment: Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism (2007) excerpt and text search

- Steigerwald, David. Wilsonian Idealism in America (1994) excerpt and text search

- Walworth, Arthur. Wilson and His Peacemakers: American Diplomacy at the Paris Peace Conference, 1919 (1986)online edition

References[edit]

- ↑ Bailey (1947) pp 23ff

Categories: [World War I] [Progressive Era]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/02/2023 18:12:09 | 15 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Fourteen_Points | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF