Mark Rothko

From Nwe

From Nwe

| Mark Rothko | |

Photograph of Mark Rothko by Conseulo Kanaga, Brooklyn Museum |

|

| Birth name | Markus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz |

| Born | September 25 1903 |

| Died | February 25 1970 (aged 66) New York City, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Field | Painting |

| Movement | Abstract expressionism, Color Field |

| Patrons | Peggy Guggenheim, John de Menil, Dominique de Menil |

Mark Rothko, born Marcus Rothkowitz, (September 25, 1903 – February 25, 1970) was a Latvian-born American painter and printmaker. Rothko was one of the most highly-regarded painters to emerge from the New York City art scene after the end of World War II.

Between the mid-1920s and the end of the 1940s, Rothko's paintings evolved from distorted figures and pseudo-primitive figures to less distinct figures known as "multiforms," then finally to the large, rectangular fields of color for which he became famous.

Many critics have hailed Rothko's work as transcendental, creating spiritual work for secular times. Rothko canvases of the 1950s and 1960s engender a sense of sublimity through their size, space, and light.[1]

Though he was classified as an abstract expressionist artist, Rothko rejected the label. His art is known for creating an experience for his audience described as otherworldly.

Childhood

Mark Rothko was born in Dvinsk, Latvia. His father was a pharmacist and an intellectual, who provided his children with a strictly secular and political upbringing. However, following the Russian pogrom against Jews, incited by the 1905 revolution, Jacob became an Orthodox Jew (Baal teshuva). Rothko’s early childhood was plagued with fear, as he witnessed the occasional violence brought down upon Jews by Cossacks attempting to stifle revolutionary uprisings. An image that remained with him throughout his adult life was that of dug-up pits, where Cossacks were alleged to have buried Jews they kidnapped and murdered. Rothko was sent to the cheder at age five, where he studied the Talmud.

Emigration to the US

Fearing that his sons were about to be drafted into the Czarist army, Rothko's father decided to emigrate to the United States, following the path of many other Jews who left Dvinsk in the wake of the Cossack purges, including two of his brothers.

Marcus started school in America in 1913 and in 1921 graduated with honors at Lincoln High School in Portland, Oregon at the age of 17. He became an active member of the Jewish community center, where he proved adept at political discussions. Like his father, Marcus was liberal and passionate about such issues as workers' rights and women’s rights to contraception.

Following graduation, he received a scholarship to Yale University which ran out after the first year. Along with the financial situation, Rothko was turned off by the bourgeoisie culture of the university and left. He would return 46 years later to receive an honorary degree.

Artistic apprenticeship

While visiting a friend in the autumn of 1923 at the Art Students League of New York, Rothko witnessed students sketching a nude model. According to Rothko, this was the beginning of his life as an artist. He was 20 years old and had taken some art classes in high school, but these were experiences far from an immediate calling. Rothko moved to New York and enrolled in the New School of Design, where one of his instructors was the artist Arshile Gorky, probably his first encounter with a member of the avant-garde. That autumn, he took courses at the Art Students League of New York taught by still life artist Max Weber, another Russian Jew. It was from Weber that Rothko began to see art as a tool of emotional and religious expression. As such, Rothko’s earliest paintings show a Weberian influence.

Rothko's circle

New York provided Rothko the experience of art from all cultures and periods. In 1928, Rothko had his own showing with a group of young artists at the Opportunity Gallery. His paintings covered dark, moody, expressionist interiors as well as urban scenes and were generally well-accepted among critics and peers. Despite some growing success, Rothko still needed to supplement his income, and in 1929, he began giving classes in painting and clay sculpture at the Center Academy where he stayed until 1952. During this time, he met Adolph Gottlieb, who, along with Barnett Newman, Joseph Sloman and John Graham, was part of a group of young artists surrounding the painter Milton Avery, who was 15 years Rothko’s senior. Avery’s stylized natural scenes, utilizing a rich knowledge of form and color, would be a tremendous influence on Rothko, whose own paintings, soon after meeting Avery, began to address similar subject matter and color, as in Rothko’s 1933/1934 Bathers, or Beach Scene.

Rothko, Gottlieb, Newman, Sloman, Graham and their mentor Avery, spent considerable time together, vacationing at Lake George and Gloucester, Massachusetts, spending their days painting and their evenings discussing art. Avery was very generous with his attention to these young artists, hosting literary readings and giving courses to them on nude drawings. During a 1932 visit to Lake George, Rothko met Edith Sachar, a jewelry designer. The two were married on November 12 and maintained, at first, a close and mutually supportive relationship.

First one-man shows

In the summer of 1933, Rothko had his first one-man show at the Portland Art Museum, mostly of drawings and aquarelles, as well as the works of Rothko’s pre-adolescent students from the Center Academy. During this time his family was unable to understand his decision to be an artist, especially at a time when the Great Depression was at its peak. Having suffered serious financial setbacks, the Rothkoviches were mystified by Rothko’s seeming indifference to financial necessity.

Returning to New York, unhampered by his lack of family support, Rothko had his first large one-man show at the Contemporary Arts Gallery, showing 15 oil paintings, mostly portraits, along with some aquarelles and drawings. In late 1935, Rothko joined with Ilya Bolotowsky, Ben-Zion, Adolph Gottlieb, Lou Harris, Ralph Rosenborg, Louis Schanker and Joe Solomon to form the Whitney Ten Dissenters, whose mission it was (according to a catalog from a 1937 Mercury Gallery show,) "to protest against the reputed equivalence of American painting and literal painting."[2]

Artistic Maturity

Rothko became a citizen of the United States in 1937, prompted by fears that the growing Nazi influence in Europe might provoke sudden deportation of American Jews. In 1940, Marcus Rothkovich changed his name to Mark Rothko. Following the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939, Rothko, along with Avery, Gottlieb, and others, left the American Artists’ Congress in protest of the Congress’ association with radical communism. He and a number of other artists formed the Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. Their agenda was to keep art free from political propaganda.

Inspiration from mythology

Some of Rothko's inspirations were rooted in philosophy and mythology. Rothko, Gottlieb and Newman read and discussed the works of Freud and Jung, in particular their respective theories concerning dreams and the archetypes of the collective unconscious. Rothko used mythological symbols in his work as a commentary on current history, which he understood from a Freudian perspective as images that refer to themselves, operating in a space of human consciousness that transcends specific history and culture. Rothko said his artistic approach was "reformed" by his study of the "dramatic themes of myth."[3]

Influence of Nietzsche

The period between Rothko's primitivist and playful urban scenes and aquarelles, and his use of transcendent fields of color, is one of transition, incorporating elements from both his early and late periods. It is marked by a rich and often complex milieu provoked mostly by two important events in Rothko’s life: the onset of World War and his reading of Friedrich Nietzsche.

The most crucial book for Rothko in this period was Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy. Nietzsche's idea that the artist has the power to transform tragedy into beauty is what Rothko attempted to demonstrate in his paintings.[4]

Break with Surrealism

Rothko’s one-man show at the Guggenheim in late 1945 resulted in only a few sales (priced between $150 and $750) and less-than-favorable reviews. Sensing that his art was becoming passé and no longer a viable medium for the direction he was moving (stimulated by Still’s abstract landscapes of color), Rothko broke with the Surrealists. He could no longer bring himself to continue interpreting the unconscious symbolism of everyday forms and he turned his efforts to pursue abstraction; in it, Rothko found release from the Surrealist program of the humanist impulse to mere "memory and hallucination." His 1945 masterpiece Slow Swirl at Edge of Sea illustrates Rothko’s newfound propensity towards abstraction. Interpreted by many critics as a meditation on Rothko’s courtship of his second wife Mell, the painting presents two humanlike forms embraced in a swirling, floating atmosphere of shapes and colors, subtle grays and browns. The rigid rectangular background foreshadows Rothko’s later experiments in pure color. The painting was completed, not coincidentally, the year the World War II ended.

Multiforms

1946 saw the creation of Rothko’s new "multiform" paintings. In viewing the catalogue raisonne, one finds a gradual metamorphosis from surrealistic, myth-influenced paintings of the early part of the decade to those highly abstract, Clyfford Still-influenced forms of pure color. The term "multiform" is applied by art critics; it was never utilized by Rothko himself, yet it is an accurate description of these paintings, which, as with his paintings of the latter part of the previous decade, are best viewed as a period of transition from that of surrealism to abstraction.

Signature period

It was not long before the "multiforms" developed into the signature style; by early 1949 Rothko exhibited these new works at the Betty Parsons Gallery. For critic Harold Rosenberg, the paintings were nothing short of a revelation. Rothko had, after painting his first "multiform," secluded himself to his home in East Hampton on Long Island, only inviting a select few, including Rosenberg, to view the new paintings.[5] The discovery of his definitive form came at a period of great distress to the artist; his mother Kate died in October 1948 and it was at some point during that winter that Rothko happened upon the striking symmetrical rectangular blocks of two to three opposing or contrasting, yet complementary colors. Additionally, for the next seven years, Rothko painted in oil only on large canvas with vertical formats. This considerably large proportion was utilized in order to overwhelm the viewer, or, in Rothko’s words, to make the viewer feel enveloped within the painting.

Many of the "multiforms" and early signature paintings display an affinity for bright, vibrant colors, particularly reds and yellows, expressing energy and ecstasy. By the mid-1950s however, close to a decade after the completion of the first "multiforms," Rothko began to employ dark blues and greens; for many critics of his work this shift in colors was representative of a growing darkness within Rothko’s personal life.

In 1958, Rothko received his first commission, for paintings for the upscale Four Seasons Restaurant in New York. From then on, he would become renowned for his work in murals. His murals for Harvard University in 1962 and in 1964 were landmarks. He also accepted a commission for the then new Seagram Building in New York. After visiting the restaurant where his paintings were to hang, he canceled and returned his first commission. The paintings were stored and some were later donated to the Tate Gallery.[6]

The Chapel

The Rothko Chapel, a gallery of Mark Rothko's work, is located adjacent to the Menil Collection in Houston, Texas. The building is small, windowless, and unassuming; a decidedly geometric, postmodern structure in a decidedly postmodern, pre-fabricated neighborhood. The Chapel, the Menil Collection, and the nearby Cy Twombly gallery were funded by Texas oil millionaires John and Dominique de Menil.

For Rothko, the Chapel was to be a destination, a place of pilgrimage far from the center of art (in this case, New York) where seekers of Rothko’s "religious" artwork, could journey. That one had to journey specifically to see his artwork implied an already sympathetic audience in an increasingly indifferent postmodernist art market. Initially, the Chapel, now non-denominational, was to be specifically Roman Catholic, and the three years Rothko worked on the project (1964-1967) he believed it would remain as such. Thus Rothko’s design of the building and the religious implications of the paintings were inspired by Roman Catholic art and architecture. Its octagonal shape is based on a Byzantine church of St. Maria Assunta, and the format of the triptychs is based on paintings of the Crucifixion.

The Chapel, which opened in 1971, is the culmination of six years of Rothko’s life and, for some viewers, it culminates a career in art that charted a gradually growing concern for the transcendent. For some, to witness these paintings is a spiritual experience in itself. However, Rothko did not live to see the chapel's completion in 1971.

Suicide

In the spring of 1968, Rothko suffered an aneurysm of the aorta, a result of his chronic high blood pressure. Ignoring doctor’s orders, Rothko continued to drink and smoke heavily, did not exercise, and maintained an unhealthy diet. However, he followed the advice not to paint pictures larger than a yard in height and turned his attention to smaller formats, including acrylics on paper. Sensing the end was near, Rothko and his financial advisor, Bernard Reis, created a foundation intended to fund "research and education" that would receive the bulk of Rothko’s work following his death. (Reis later sold the paintings to the Marlborough Gallery at a considerable loss and pocketed the difference with Gallery representatives, the result of which was one of the longest and most heavily hyped legal battles in art history.)

On February 25, 1970, Oliver Steindecker, Rothko’s assistant, found the artist in his kitchen, lying dead from suicide. During an autopsy it was revealed he had overdosed on anti-depressants. He was 66 years old.

Legacy

The settlement of his estate became the subject of the famous Rothko Case. For nearly a dozen years beginning in 1971 a battle ensued between Rothko's executors, all of them his good friends, and his two children, who accused the executors of waste and fraud, and by the ensuing appeals and related litigation. As a result, many of his paintings, which had been sold or consigned by his estate to the Marlborough Gallery in Manhattan at deflated prices, were donated to museums.[7]

In early November, 2005, Rothko's 1953 oil on canvas painting, Homage to Matisse, broke the record of any post-war painting at a public auction selling for $22.5 million.

In May 2007 Rothko's 1950 painting White Center (Yellow, Pink and Lavender on Rose), broke this record again, selling at auction for $72.8 million at Sotheby's New York. The painting was sold by philanthropist David Rockefeller.[8] There was no mention of who the buyer was.

A previously unpublished manuscript by Rothko about his philosophies on art, entitled The Artist's Reality, edited by his son, Christopher Rothko, was issued by Yale University Press in 2004.

A song commemorating Mark Rothko was penned by Dar Williams for her album, The Honesty Room. It is titled The Mark Rothko Song.

Notes

- ↑ Indepth Arts News: On the Sublime: Mark Rothko, Yves Klein, James Turrell Exhibition 2001 at Guggenheim Museum, Berlin. Absolutearts.com. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ↑ The Ten Whitney Dissenters Louisschanker.info. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ↑ Rothko Project Hope Art Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ↑ Mark Rothko – Inspires Wobi Office Wobi Office. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ↑ James E.B. Breslin, Mark Rothko - A Biography (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993, ISBN 0226074056).

- ↑ Abigail Cain, The Story behind Rothko’s Famed Seagram Murals Mark Rothko Artsy, November 18, 2016. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ↑ Judith H. Dobrzynski, A Betrayal The Art World Can't Forget; The Battle for Rothko's Estate Altered Lives and Reputations New York Times, November 2, 1998. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ↑ Carol Vogel, Rothko Breaks a Record for Contemporary Art New York Times, May 16, 2007. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Breslin, James E.B. Mark Rothko - A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. ISBN 0226074056

- Chave, Anne. Mark Rothko, 1903-1970: A Retrospective. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

- Herskovic, Marika. American Abstract Expressionism of the 1950s, an illustrated survey: with artists' statements, artwork and biographies. New York: New York School Press, 2003. ISBN 0967799414

- Hopkins, David, After Modern Art: 1945-2000. Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 019284234X

- Rothko, Mark. Christopher Rothko (ed.). The Artist's Reality: Philosophies of Art. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 9780300102536

- Rothko, Mark. "The Individual and the Social." In Charles Harrison and Paul Wood (eds.), Art in Theory 1900-1990 An Anthology of Changing Ideas, (563-565). Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers, Ltd. 1993. ISBN 0631165754

- Seldes, Lee. The Legacy of Mark Rothko. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1978. ISBN 0030147514

- Waldman, Diane. Mark Rothko 1903-1970: a retrospective. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. 1988. ISBN 0892070145

External links

All links retrieved November 6, 2022.

- The Rothko Chapel

- Horsley, Carter B. Mark Rothko Thecityreview.com.

- Valiunas, Algis. 2006. Spirit in the Abstract Firstthings.com.

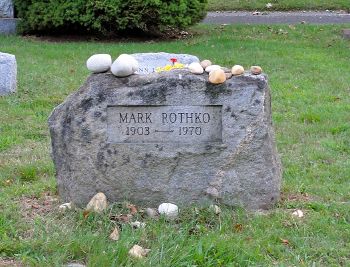

- Mark Rothko's Gravesite, Find A Grave.

- Mark Rothko, Artcyclopedia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 22:16:21 | 30 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mark_Rothko | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF