History Of Japan

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia The history of Japan, the rich, powerful island nation off the coast of China and Korea, is typically divided into three stages: the period of interaction with China and East Asia; a period of isolation; and the opening-up of the country to the world. For contemporary Japan see: Japan.

Contents

Early Japan[edit]

The mythology of ancient Japan is contained within the Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters) which records the creation myth of Japan and its lineage of Emperors to the Sun Goddess Amaratsu. Large portions of this book are Chinese mythology and the distinction of what is truly Japanese and what is Chinese is continually questioned.

In the myth of Japan's creation the two gods Isanagi and Isanami swirled the primordial soup below the bridge of heaven with a rod and when retrieving the rod the drops of liquid that formed and dropped created the first islands of Japan.

Archaeology[edit]

Korean and Chinese influence[edit]

Throughout history, Japan has gotten many influences from Korea and China. They have been modified to fit Japanese needs, in most aspects. Some include chopsticks, the Chinese writing system and Chinese-style poetry. Buddhism also arrived in Japan via Korea.

Nara and Heian[edit]

In early Japan, every emperor moved the capital to a place of his own choosing. The first permanent capital was established by Empress Gemmei at Heijokyo, present-day Nara, in 710. When the influence of nearby Bhuddist monasteries on the capital became too large, the capital was moved and a new capital established in Heiankyo, modern Kyoto, in 794. Heiankyo remained the seat of government until the end of the Heian Period in 1185 when court authority had given way to the feudal rule of warrior clans and the rise of the Shogunate established at Kamakura by Minamoto no Yoritomo. The emperor and remnants of the court nobility continued to reside in Kyoto until the 19th century, but without any political power.

The Fujiwara clan[edit]

The Fujiwara clan was the most powerful family of court nobility throughout much of the Nara and Heian periods. They monopolized the position of Regent and issued edicts in the emperors' name. This system removed so much power from the emperors that by the 11th century the emperors preferred to resign and wield power as retired emperors.

Development of Buddhism[edit]

Buddhism had been introduced to Japan from Korea in the sixth century, but its influence was small until it was embraced by Emperor Shomu in the first half of the 8th century. Shomu's daughter who twice ruled as empress (Empress Koken and Empress Shotoken, respectively) continued to increase Buddhism's influence. At the same time, Buddhist concepts began to be associated with older elements of Shinto.

Feudal Era[edit]

Kyoto served as Japan's imperial capital for more than a thousand years (794-1868) and in the 21st century is still one of Japan's leading cultural centers.

Vassalage and of great military houses[edit]

Kamakura Military Government[edit]

The Ashikaga clan[edit]

Civil War and Unification[edit]

The Tokugawa Era, 1600-1868[edit]

In 1603, the Tokugawa Shogunate (military dictatorship) ushered in a long period of isolation from foreign influence in order to secure its power. For 250 years this policy enabled Japan to enjoy stability and a flowering of its indigenous culture.Christian missions[edit]

Social structure[edit]

Japanese society had an elaborate social structure, in which everyone knew their place and level of prestige. At the top were the emperor and the court nobility, invincible in prestige but weak in power. Next came the "bushi" of shogun, daimyo and layers of feudal lords whose rank was indicated by their closeness to the Tokugawa. They had power. The "daimyo" comprised about 250 local lords of local "han" with annual outputs of 50,000 or more bushels of rice. The upper strata was much given to elaborate and expensive rituals, including elegant architecture, landscaped gardens, nō drama, patronage of the arts, and the tea ceremony.

Then came the 400,000 warriors, called "samurai", in numerous grades and degrees. A few upper samurai were eligible for high office; most were foot soldiers (ashigaru) with minor duties. The samurai were affiliated with senior lords in a well-established chain of command. The shogun had 17,000 samurai retainers; the daimyo each had hundreds. Most lived in modest homes near their lord's headquarters, and lived off of hereditary rights and stipends. Together these high status groups comprised Japan's ruling class making up about 6% of the total population.

Lower orders divided into two main segments—the peasants—80% of the population—whose high prestige as producers was undercut by their burden as the chief source of taxes. They were illiterate and lived in villages controlled by appointed officials who kept the peace and collected taxes.

Near the bottom of the prestige scale—but much higher up in terms of income and life style—were the merchants and artisans of the towns and cities. They had no political power, and even rich merchants found it difficult to rise in the world in a society in which place and standing were fixed at birth. Finally came the entertainers, prostitutes, day laborers and servants, and the thieves, beggars and hereditary outcasts.[1]

Economy[edit]

The Tokugawa era brought peace, and that brought prosperity to a nation of 31 million, 80% of them rice farmers. Rice production increased steadily, but population remained stable. Rice paddies grew from 1.6 million chō in 1600 to 3 million by 1720.[2] Improved technology helped farmers control the all-important flow of water to their paddies. The daimyo's operated several hundred castle towns, which became loci of domestic trade. Large-scale rice markets developed, centered on Edo and Osaka. Merchants invented credit instruments to transfer money, and currency came into common use. In the cities and towns, guilds of merchants and artisans met the growing demand for goods and services.[3]

The merchants benefited enormously, especially those with official patronage. The samurai, forbidden to engage in farming or business but allowed to borrow money, borrowed too much. The bakufu and daimyos raised taxes on farmers, but did not tax business, so they too fell into debt. By 1750 rising taxes incited peasant unrest and even revolt. The nation had to deal somehow with samurai impoverishment and treasury deficits. The financial troubles of the samurai undermined their loyalties to the system, and the empty treasury threaten the whole system of government. One solution was reactionary—with prohibitions on spending for luxuries. Other solutions were modernizing, with the goal of increasing agrarian productivity. The eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (in office 1716-1745) had considerable success, though much of his work had to be done again between 1787 and 1793 by the shogun's chief councilor Matsudaira Sadanobu (1759-1829). Others shoguns debased the coinage to pay debts, which caused inflation.

By 1800 the commercialization of the economy grew rapidly, bringing more and more remote villages into the national economy. Rich farmers appeared who switched from rice to high-profit commercial crops and engaged in local money-lending, trade, and small-scale manufacturing. Some wealthy merchants sought higher social status by using money to marry into the samurai class.

A few domains, notably Chōsū and Satsuma, used innovative methods to restore their finances, but most sunk further into debt. The financial crisis provoked a reactionary solution near the end of the "Tempo era" (1830-1843) promulgated by the chief counselor Mizuno Tadakuni. He raised taxes, denounced luxuries and tried to impede the growth of business; he failed and it appeared to many that the continued existence of the entire Tokugawa system was in jeopardy.[4]

Edo/Tokyo[edit]

Edo (Tokyo) had been a small settlement for 400 years but began to grow rapidly after 1603 when Shogun Ieyasu built a fortified city as the administrative center of the new Tokugawa Shogunate. Edo resembled the capital cities of Europe with military, political, and economic functions. The Tokugawa political system rested on both feudal and bureaucratic controls, so that Edo lacked a unitary administration. The typical urban social order was composed of samurai, unskilled workers and servants, artisans, and businessmen. The artisans and businessmen were organized in officially sanctioned guilds; their numbers grew rapidly as Tokyo grew and became a national trading center. Businessmen were excluded from government office, and in response they created their own subculture of entertainment, making Edo a cultural as well as a political and economic center. With the Meiji Restoration, Tokyo's political, economic, and cultural functions simply continued as the new capital of imperial Japan.

Three cultures[edit]

Three distinct cultural traditions operated during the Tokugawa era, having little to do with each other. In the villages the peasants had their own rituals and localistic traditions. In the high society of the imperial court, daimyos and samurai, Chinese cultural influence was paramount, especially in the areas of ethics and political ideals. Neo-Confucianism became the approved philosophy, and was taught in official schools; Confucian norms regarding personal duty and family honor became deeply implanted in elite thought. Equally pervasive was the Chinese influence in painting, decorative arts and history, economics, and natural science. One exception came in religion, where there was a revival of Shinto, which had originated in Japan. Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801) freed Shinto from centuries of Buddhist accretions and gave a new emphasis to the myth of imperial divine descent, which later became a political tool for imperialist conquest until it was destroyed in 1945.

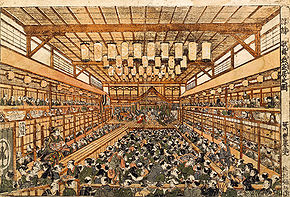

The third cultural level was the popular art of the low-status artisans, merchants and entertainers, especially in Edo and other cities. It revolved around "ukiyo", the floating world of the city pleasure quarters and theaters that was officially off-limits to samurai. Its actors and courtesans were favorite subjects of the woodblock color prints that reached high levels of technical and artistic achievement in the 18th century. They also appeared in the novels and short stories of popular prose writers of the age like Ihara Saikaku (1642-1693). The theater itself, both in the puppet drama and the newer kabuki, as written by the greatest dramatist, Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724), relied on the clash between duty and inclination in the context of revenge and love.

The Meiji Era: 1868-1912[edit]

Following the Treaty of Kanagawa with the United States in 1854, Japan opened its ports and began to intensively modernise and industrialise. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Japan became a regional power that was able to defeat the forces of both China and Russia. It occupied Korea, Formosa (Taiwan), and southern Sakhalin Island.

Revolt[edit]

The rule of the Shoguns came to an end in the middle of the 19th century during a brief but bloody period of conflict known as the Meiji Restoration, which was triggered in part by American Commodore Matthew Perry's 1853 naval expedition to Japan. During the Restoration a large number of young samurai from minor families, tired of the government's mishandling of the country and feeling that if action was not taken Japan would be dominated by western countries, initiated an armed revolt to restore imperial rule. Most samurai from the more powerful families sided with the Shogun, fearing that the minor families would replace them if the revolt was successful. Nonetheless, the shogunate was done away with in 1867 and the imperial period began. The capital was moved to Edo, which was renamed Tokyo; by the early twenty-first century, it had become the center of the world's largest urban conglomeration. In 1898, the last of the "unequal treaties" with Western powers was removed, signaling Japan's new status among the nations of the world. In a few decades, by creating modern social, educational, economic, military, and industrial systems, the Emperor Meiji's "controlled revolution" had transformed a feudal and isolated state into a world power.

Imperialism[edit]

The phrase "imperial period" refers to Japan competing with European powers and the United States for colonies and influence during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The high point of Japanese prestige was the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, in which Japan became the principal power in Manchuria and consolidated its control of Korea and over the southern portion of Sakhalin Island and Taiwan. In World War I Japan fought over a limited number of German-controlled pacific colonies as part of the Anglo-Japanese alliance, gaining control of Qingdao (Tsingtao), a German-controlled colony in China, as well as several German-controlled Pacific Islands, the most significant being Truk lagoon.

Economy and empire; war and defeat: 1912-1950[edit]

Hirohito was the Showa Emperor 1926-89 after serving as regent since 1921.

1930s[edit]

In 1931 Japan occupied Manchuria ("Dongbei"), setting up the puppet state of Manchukuo. In 1933, Japan resigned from the League of Nations. By 1936, during the reign of Emperor Hirohito, the Japanese Empire adopted the catch-phrase "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere".

While the genocide and war crimes of Nazi Germany and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia were motivated by far-left politics just as the Ottoman Empire's genocide against Christians were motivated by Islam, Japan's war crimes were motivated by Bushido (Samurai way), which combines the martial aspects of Zen Buddhism and the nationalist aspects of Nichiren Buddhism while fueled by western imperialism.

In 1937 Japan launched a full-scale invasion of China, seizing most of the coastline and population centers. The U.S. undertook large scale military and economic aid to China and demanded Japanese withdrawal. Instead of withdrawing Japan took over French Indochina in 1940-41; the U.S., Britain and the Netherlands cut off oil imports in 1941, which accounted for over 90% of Japan's oil supply. Desultory negotiations with the US led nowhere. Japan attacked U.S. forces at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, triggering America's entry into World War II.

The increasingly powerful Japanese armed forces, came to dominate Japanese politics, assassinating politicians whom they deemed insufficiently devoted to the Emperor and nation. For the next nine years, the military leadership installed its own members (such as Hideki Tojo, chief Japanese strategist of World War II) or, occasionally, civilians who were completely identified with their agenda, as prime minister. In 1937 Japan's joined the "anti-Comintern pact" with Nazi Germany, leading to (exaggerated) American fears of a close relationship. In fact Germany and Japan remained distant until the latter part of the wwar. Thus Germany refused to give Japan blueprints for advanced weapons or synthetic oil.

World War II[edit]

In a blitzkrieg operation Japan rapidly expanded at sea and land, capturing Singapore and the Philippines in early 1942, and threatening India and Australia. Meanwhile, fighting in China itself largely came to standstill, and Japan remained on neutral terms with the Soviet Union. The U.S. Navy stopped Japanese expansion at two great naval battles in 1942, the Battle of the Coral Sea and the Battle of Midway. Japanese overextension resulted in defeat in the Guadalcanal Campaign. Japanese sea power was destroyed by the U.S. Navy in 1944 at the Battle of the Philippine Sea and the Battle of Leyte Gulf. The U.S. industrial economy was ten times larger than Japan's, and was manifest in warplanes and warships as two main thrusts approached Japan, one through the central Pacific and one through the Philippines.

Systematic destruction of Japan's industrial centers began in early 1945 with the B-29 raids. The Emperor refused to surrender until shocked by two atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and Soviet entry into the war in August 1945.

On the conventional and atomic bombings see Bombing of Japan

Total Japanese military fatalities between 1937 and 1945 were 2.1 million; most came in the last year of the war. Starvation or malnutrition-related illness accounted for roughly 80 percent of Japanese military deaths in the Philippines, and 50 percent of military fatalities in China. The aerial bombing of a total of 65 Japanese cities appears to have taken a minimum of 400,000 and possibly closer to 600,000 civilian lives (over 100,000 in Tokyo alone, over 200,000 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki combined, and 80,000-150,000 civilian deaths in the battle of Okinawa). Civilian death among settlers who died attempting to return to Japan from Manchuria in the winter of 1945 were probably around 100,000.[5]

U.S. occupation[edit]

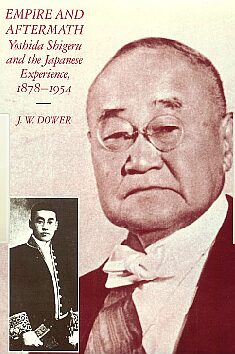

- See Shigeru Yoshida

After its defeat in World War II, Japan was occupied by the U.S. until 1951, and recovered from the effects of the war to become an economic power, staunch American ally and a democracy. While Emperor Hirohito was allowed to retain his throne as a symbol of national unity, actual power rests in networks of powerful politicians, bureaucrats, and business executives.

Japan was stripped of its overseas possessions and retained only the home islands and Okinawa. Manchukuo was dissolved, and Manchuria was returned to China; Japan renounced all claims to Formosa; Korea was occupied and divided by the U.S. and the Soviet Union; and the U.S. became the sole administering authority of the Ryukyu, Bonin, and Volcano Islands. The Soviets rehgained southern Sakhalin and took over the Kurile islands. Japan vehemently rejects Soviet control of the Kuriles, and tension over the issue continues high into the 21st century.

Japan was placed under the nominal international control of the Allies, and in actuality was ruled by one person, through the Supreme Commander, Gen. Douglas MacArthur. U.S. objectives were to ensure that Japan would become a peaceful nation and to establish democratic self-government supported by the freely expressed will of the people. Political, economic, and social reforms were introduced, such as a freely elected Japanese Diet (legislature) and universal adult suffrage. The country's new constitution took effect in May 1947. The United States and 45 other Allied nations signed the Treaty of Peace with Japan in September 1951 and Japan regained full sovereignty in April 1952. The 1972 reversion of Okinawa completed the U.S. return of control of these islands to Japan.

Shigeru Yoshida (1878-1967) played the central role as prime minister between 1946 and 1954 (with one interruption). His goal was rapid rebuilding Japan and cooperation with the American Occupation. He led Japan to adopt the “Yoshida Doctrine”, based on three tenets: economic growth as the primary national objective, no involvement in international political-strategic issues, and the provision of military bases to the United States. The Yoshida Doctrine proved immensely successful.

Economic miracle: 1950-1990[edit]

Economic stagnation: 1990-2009[edit]

The economy experienced a major slowdown starting in the 1990s following three decades of unprecedented growth, but Japan still remains a major economic power, both in Asia and globally.

When the worldwide Recession of 2008 hit, it first appeared Japan would hold up better than other industrial countries. However exports of cars and electronics has plunged, leading to a dramatic 12% drop in GDP.

Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011[edit]

A massive 8.9-magnitude earthquake and several powerful aftershocks struck the eastern coast of Japan on March 11, 2011 (12:46 a.m. in Washington), triggering a tsunami that devastated the coastline north of Tokyo with waves up to 10 meters (33 ft.) high. The earthquake epicenter was in the western Pacific Ocean, 130 kilometers east of Sendai, Honshu island. The earthquake occurred along the subduction zone between two tectonic plates.

The Japan Meteorological Agency said the earthquake was the strongest in the country's history;[6] the death toll is expected to top 10,000 people; Prime Minister Naoto Kan called it the nation's worst crisis since World War II.[7]

The earthquake has caused three nuclear power plant cooling systems to fail and those affected reactors. Thousands of residents were evacuated.[8]

After the earthquake and tsunami, entire towns in Japan are impossible to reach. But search and rescue teams are fanning out in what will be a lengthy, complex endeavor.

See also[edit]

Basic Further reading[edit]

- Allinson, Gary D. The Columbia Guide to Modern Japanese History. (1999). 259 pp. excerpt and text search

- Allinson, Gary D. Japan's Postwar History. (2nd ed 2004). 208 pp. excerpt and text search

- Beasley, W. G. The Modern History of Japan (1963) online edition

- Clement, Ernest Wilson. A Short History of Japan (1915), 190pp online edition

- Cullen, L. M. A History of Japan, 1582-1941: Internal and External Worlds (2003) online edition

- Edgerton, Robert B. Warriors of the Rising Sun: A History of the Japanese Military. (1999). 384 pp. excerpt and text search

- Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present (2003) online edition; also excerpt and text search

- Hall John W. Japan: From Prehistory to Modern Times. 1970.

- Hane, Mikiso. Modern Japan: A Historical Survey (2nd ed 1992), 474pp online edition

- Huffman, James L., ed. Modern Japan: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism. (1998). 316 pp.

- Hunter Janet. Concise Dictionary of Modern Japanese History. 1984.

- Jansen, Marius B. The Making of Modern Japan (2002) excerpts and search online

- McClain, James L. Japan: A Modern History. (2001). 512 pp. excerpt and text search

- Perez, Louis G. The History of Japan (1998) 244pp online edition

- Perkins, Dorothy. Encyclopedia of Japan: Japanese History and Culture, from Abacus to Zori. (1991). 410 pp.

- Reischauer, Edwin O. Japan: The Story of a Nation. 1990.

- Stockwin, J. A. A. Dictionary of the Modern Politics of Japan. (2003). 291pp online edition

- Tipton, Elise. Modern Japan: A Social and Political History (2002) excerpt and text search

- Totman, Conrad. A History of Japan. (2nd ed. 2000). 620 pp.; stress on environment online excerpts and search

Advanced Bibliography[edit]

Surveys and reference[edit]

- Allinson, Gary D. The Columbia Guide to Modern Japanese History. (1999). 259 pp. excerpt and text search

- Beasley, W. G. The Modern History of Japan (1963) online edition

- Clement, Ernest Wilson. A Short History of Japan (1915), 190pp online edition

- Cullen, L. M. A History of Japan, 1582-1941: Internal and External Worlds (2003) online edition

- Edgerton, Robert B. Warriors of the Rising Sun: A History of the Japanese Military. (1999). 384 pp. excerpt and text search

- Goedertier Joseph M. A. Dictionary of Japanese History. 1968.

- Gordon, Andrew. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present (2003) online edition; also excerpt and text search

- Hall John W. Japan: From Prehistory to Modern Times. 1970.

- Hane, Mikiso. Modern Japan: A Historical Survey (2nd ed. 1992), 474pp online edition

- Huffman, James L., ed. Modern Japan: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism. (1998). 316 pp.

- Hunter Janet. Concise Dictionary of Modern Japanese History. 1984.

- Jansen, Marius B. The Making of Modern Japan (2002) excerpts and search online

- McClain, James L. Japan: A Modern History. (2001). 512 pp. excerpt and text search

- Mosk, Carl. Japanese Industrial History: Technology, Urbanization, and Economic Growth. M. E. Sharpe, 2001. 293 pp.

- Najita, Tetsuo. Japan: The Intellectual Foundations of Modern Japanese Politics (1980), 200 year interpretation excerpt and text search

- Perez, Louis G. The History of Japan (1998) 244pp online edition

- Perkins, Dorothy. Encyclopedia of Japan: Japanese History and Culture, from Abacus to Zori. (1991). 410 pp.

- Reischauer, Edwin O. Japan: The Story of a Nation. 1990.

- Reischauer, Edwin O., and Albert M. Craig. Japan, Tradition and Transformation 1978.

- Sims, Richard. Japanese Political History since the Meiji Renovation, 1868-2000. (2001). 395 pp.

- Stockwin, J. A. A. Dictionary of the Modern Politics of Japan. (2003). 291pp online edition

- Tipton, Elise. Modern Japan: A Social and Political History (2002) excerpt and text search

- Totman, Conrad. A History of Japan. (2nd ed. 2000). 620 pp.; stress on environment online excerpts and search

- Totman, Conrad. Early Modern Japan (1995) excerpt and text search

- Umesao, Tadao. An Ecological View of History: Japanese Civilization in the World Context. Melbourne: Trans Pacific Press, 2003. 208 pp.

- Van Sant, John, Peter Mauch, and Yoneyuki Sugita. Historical Dictionary of United States-Japanese Relations (2007) 344 pp. online review

to 1860[edit]

- Hall, John W. ed. Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. IV, Early Modern Japan. (1991). 831pp

- Hane, Mikiso. Premodern Japan: A Historical Survey (1991)

- Hayami, Akira; Saito, Osamu; and Toby, Ronald P., eds. The Economic History of Japan, 1600-1990. Vol. 1: Emergence of Economic Society in Japan, 1600-1859. (2004). 420 pp.

- Jansen, Marius B., ed. The Cambridge History of Japan. Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century. (1989). 828 pp. excerpt and text search

- Sansom, Sir George B. A History of Japan, 3 vols. 1963, in dense, sophisticated prose excerpts and search vol 1 to 1334, excerpts and search vol 2 to 1615 excerpts and search vol 3 to 1867

- Totman, Conrad. "Tokugawa Peasants: Win, Lose, or Draw?" Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 41, No. 4. (Winter, 1986), pp. 457–476. in English; in JSTOR

- Wilson, George M. Patriots and Redeemers in Japan: Motives in the Meiji Restoration. (1992). 201 pp.

- Yamamura Kozo, ed. Cambridge History of Japan, Vol. III. Medieval Japan. (1990).

- Yamamura, Kozo. "Toward a Reexamination of the Economic History of Tokugawa Japan, 1600-1867." Journal of Economic History 1973 33(3): 509-546. Issn: 0022-0507 Fulltext: in Jstor

1860 to 1945[edit]

- Cohen, Jerome B. Japan's Economy in War and Reconstruction (1949) 545 pp. online edition

- Dower, John W. War without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War. Pantheon, 1986. 398 pp. excerpt and text search

- Duus, Peter, ed. The Cambridge History of Japan: Vol. 6: The Twentieth Century. (1989). 866 pp.

- Ericson, Steven J. The Sound of the Whistle: Railroads and the State in Meiji Japan. (1996). 506 pp.

- Iriye, Akira. Power and Culture: The Japanese-American War, 1941-1945 (1981),

- Jansen, Marius B. and Rozman, Gilbert, eds. Japan in Transition, from Tokugawa to Meiji. (1986). 485 pp. modernization models

- Keene, Donald. Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World , 1852-1912. (2002). 928 pp.

- LaFeber, Walter. The Clash: A History of U.S.-Japan Relations. (1997). 544 pp.

- Sims, Richard. Japanese Political History since the Meiji Renovation, 1868-2000. Palgrave, 2001. 395 pp.

- Sugihara, Kaoru. Japan, China, and the Growth of the Asian International Economy, 1850-1949 - Vol. 1 (2005) online edition

Occupation: 1945-1952[edit]

- Buckley, Roger. Occupation Diplomacy: Britain, the United States and Japan, 1945-1952. (1982). 294 pp.

- Cohen, Jerome B. Japan's Economy in War and Reconstruction (1949) 545 pp. online edition

- Cohen, Theodore. Remaking Japan: The American Occupation as New Deal. (1987). 526 pp.

- Dower, John W. Empire and Aftermath: Yoshida Shigeru and the Japanese Experience, 1878-1954 (1988), the major scholarly study excerpt and text search

- Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. (1999). 688 pp. excerpt and text search

- Eldridge, Robert. The Origins of the Bilateral Okinawa Problem: Okinawa in Postwar US-Japan Relations, 1945-1952 (2001) excerpt and text search

- Finn, Richard B. Winners in Peace: MacArthur, Yoshida, and Postwar Japan. (1992). 413 pp. excerpt and text search

- Hane, Mikiso. Eastern Phoenix: Japan since 1945 (1996)

- Harvey, Robert. American Shogun: General MacArthur, Emperor Hirohito, and the Drama of Modern Japan. (2006). 480 pp.

- Hellegers, Dale M. We, the Japanese People: World War II and the Origins of the Japanese Constitution. (2 vol. 2002). 826 pp.

- Hewes Jr., Laurence I. Japan -- Land and Men: An Account of the Japanese Land Reform Program, 1945-51 154 pgs. (1955) online edition

- Hirano, Kyoko. Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: The Japanese Cinema under the American Occupation, 1945-1952. (1992). 400 pp.

- Koseki, Shoichi. The Birth of Japan's Postwar Constitution. (1997). 257 pp online edition

- Koshiro, Yukiko. Trans-Pacific Racisms and the U.S. Occupation of Japan. (1999). 295 pp.

- Molasky, Michael S. The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa: Literature and Memory. (1999). 244 pp.

- Moore, Ray A. and Robinson, Donald L. Partners for Democracy: Crafting the New Japanese State under MacArthur. (2002). 409 pp.

- Orbaugh, Sharalyn. Japanese Fiction of the Allied Occupation: Vision, Embodiment, Identity. (2007). 515 pp.

- Sandler, Mark, ed. The Confusion Era: Art and Culture in Japan during the Allied Occupation, 1945-52. (1998). 112 pp.

- Schonberger, Howard B. Aftermath of War: Americans and the Remaking of Japan, 1945-1952 (1989)

- Schaller, Michael. The American Occupation of Japan: The Origins of the Cold War in Asia (1987) excerpt and text searcj

- Shibata, Masako. Japan and Germany under the US Occupation: A Comparative Analysis of Post-War Education Reform. (2005). 212 pp.

- Sodei, Rinjiro. Dear General MacArthur: Letters from the Japanese during the American Occupation. (2001). 308 pp., primary sources

- Takemae, Eiji. Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy. (2002). 800 pp.

- VanStaaveren, Jacob. An American in Japan, 1945-1948: A Civilian View of the Occupation. (1995). 286 pp. primary course

- Ward, Robert E. and Yoshikazu, Sakamoto. Democratizing Japan: The Allied Occupation. (1987). 456 pp.

- Williams, Justin, Sr. Japan's Political Revolution Under MacArthur: A Participant's Account. (1979). 317 pp. primary source

- Yoshida, Shigeru. The Yoshida Memoirs: The Story of Japan in Crisis 1961, primary source online edition

Since 1952[edit]

- Allinson, Gary D. Japan's Postwar History. (2nd ed 2004). 208 pp. excerpt and text search

- Duus, Peter, ed. The Cambridge History of Japan: Vol. 6: The Twentieth Century. (1989). 866 pp.

- Hane, Mikiso. Eastern Phoenix: Japan since 1945 (1996) online edition

- LaFeber, Walter. The Clash: A History of U.S.-Japan Relations. (1997). 544 pp.

- Ohtsu, Makoto. Inside Japanese Business: A Narrative History, 1960-2000. (2002). 459 pp.

- Sims, Richard. Japanese Political History since the Meiji Renovation, 1868-2000. Palgrave, 2001. 395 pp.

- Sugihara, Kaoru. Japan, China, and the Growth of the Asian International Economy, 1850-1949 - Vol. 1 (2005) online edition

- Sumiya, Mikio, ed. A History of Japanese Trade and Industry Policy. (2000). 662 pp.

Cultural history[edit]

- Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Buddhism: A History. Vol. 2. Japan. (1989). 509 pp.

- Duus, Peter, ed. The Japanese Discovery of America: A Brief History with Documents. (1997). 226 pp.

- Earhart, H. Byron. Japanese Religion: Unity and Diversity (1974).

- Guttmann, Allen and Thompson, Lee. Japanese Sports: A History. (2001). 368 pp.

- Harootunian, Harry. History's Disquiet: Modernity, Cultural Practice, and the Question of Everyday Life. (2000). 182 pp.

- Keene, Donald. Japanese Literature: An Introduction for Western Readers (1955)

- Morris, Ivan. The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan (1964)

- Kitagawa Joseph M. Religion in Japanese History. 1966.

- Kuitert, Wybe. Themes in the History of Japanese Garden Art (2002). 283 pp.

- Leiter, Samuel L. A Kabuki Reader: History and Performance. (2002). 430 pp.

- Mason, Penelope. History of Japanese Art. (1993). 431 pp.

- Morris-Suzuki, Tessa. A History of Japanese Economic Thought (1991) online edition

- Munsterberg, Hugo. The Arts of Japan: An Illustrated History (1957)

- Roberts, Laurance P. A. Dictionary of Japanese Artists. Tokyo: 1976.

- Sansom, Sir George B. Japan, A Short Cultural History. 1978. online edition

- Siever, Sharon Flowers in Salt: The Beginning of Feminine Consciousness in Modern Japan (1983)

- Standish, Isolde. A New History of Japanese Cinema: A Century of Narrative Film. (2005). 452 pp.

- Wakabayashi, Bob Tadashi. Modern Japanese Thought. (1998). 403 pp. excerpt and text search

Historiography[edit]

- Allinson, Gary D. The Columbia Guide to Modern Japanese History. (1999). 259 pp. excerpt and text search

- Beasley W. G., and E. G. Pulleyblank, eds. Historians of China and Japan. 1961. online edition

- Hardacre, Helen and Kern, Adam L., eds. New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan. (1997). 782 pp.

Primary sources[edit]

- Cook, Haruko Taya and Cook, Theodore F. eds. Japan at War: An Oral History. (1992). 504 pp., World War II homefront excerpt and text search

- Huffman, James L. ed. Modern Japan: A History in Documents (2004)

- Tsunoda, Ryusaku, W. T. de Bary, and Donald Keene, eds. Sources of Japanese Tradition. 1958.

- Yoshida, Shigeru. The Yoshida Memoirs: The Story of Japan in Crisis 1961, on Occupation, 1945–51 online edition

notes[edit]

- ↑ Totman (2000) 225-30

- ↑ One chō, or chobu, equals 2.45 acres.

- ↑ Totman (2000) ch 11

- ↑ McClain (2002) pp 128-29

- ↑ John Dower, "Lessons from Iwo Jima," Perspectives (Sept 2007) 45#6 pp 54-56 at [1]

- ↑ Japan Quake - Tsunami

- ↑ https://www.usatoday.com/news/world/2011-03-13-japan-earthquake_N.htm

- ↑ Radiation Levels Surge Outside Two Nuclear Plants in Japan.

Categories: [Japanese History] [Japan] [Asian History]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/01/2023 15:17:37 | 40 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/History_of_Japan | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF