New Deal

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia

The New Deal was a group of otherwise disjointed programs conducted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, throughout the Great Depression, especially from 1933–36. His program had three aspects: Relief, Recovery and Reform. It sought to provide immediate Relief for the millions of unemployed in the Great Depression. It was intended to promote Recovery of the economy to normal standards—a goal he did not fully achieve. It involved a series of Reforms, especially in the financial system and labor relations. The basic issue was how to deal with the severely damaged economy—and great social misery—caused by three years of the Great Depression. Conservatives endorsed parts of the First New Deal (the 1933 programs) and rejected the more radical Second New Deal (the 1934–35 programs).

The New Deal was popular among voters leading to the formation of the New Deal Coalition, which made the Democrats the majority party during the Fifth Party System into the 1960s. However, a Conservative Coalition took control of Congress in 1937 and blocked nearly all additional programs; during the war years (1941–45) the conservatives successfully rolled back many of the relief efforts on the grounds they were no longer needed since full employment was achieved. The "reforms" that regulated the economy were mostly dropped in the deregulation era (1974–87), except for oversight of Wall Street by the SEC, which conservatives approved because it increased investor confidence.

The New Deal Coalition dominated national politics until it split apart in the 1960s. Ever since it has been the holy grail of liberals seeking to restore their former glory.

Although the New Deal did not fully solve the economic catastrophe that was on the verge of destroying the US economy in early 1933, it achieved many of its objectives and the period of 1933–37 saw some sectors return to economic growth.

Contents

- 1 Broker State

- 2 Economic planning

- 3 First and Second New Deals

- 4 Foreign policy

- 5 Relief, Recovery, and Reform

- 6 The Origins of the New Deal

- 7 The First Hundred Days

- 8 Reform: (NIRA)

- 9 Second New Deal

- 10 Government Role: balance labor, business and farming

- 11 Stagnation of the economy: Negative supply side

- 12 African Americans

- 13 Double dip recession

- 14 World War II and the end of the New Deal

- 15 Conflicting interpretation of the New Deal economic policies

- 16 The legacies of the New Deal

- 17 Brain trust

- 18 Main programs

- 19 Art and music

- 20 See also

- 21 Notable New Deal programs

- 22 Further reading

- 23 External links

- 24 Notes

Broker State[edit]

The New Deal created the "Broker State", where different interest groups compete in the national market. The government became a mediator between those interest groups, giving power to those who has enough political and economic power to demand it. One of the limitations of this Broker States was that minority groups were often ignored since they did not have political power.

Economic planning[edit]

- Main article: Economic planning

As the Depression set in, terms like “planned economy” and “national planning” became the watchwords of the day.[2] They had been used by theoreticians for years and popularized by best-selling writers like George Soule and Stuart Chase, who lauded the Soviet Gosplan (central planning), asking plaintively, “Why should the Russians have all the fun of remaking a world?” One prominent member of the Brain trust was Rexford Guy Tugwell. Tugwell was a follower of the school of thought known as "Institutional Economics". His official position was assistant secretary of agriculture, that is, second in command to Henry A. Wallace, but his influence extended far beyond that. Tugwell had traveled to the Soviet Union in 1927 and observed through scientific economic planning the Soviets were able to “carry out their industrial operations with a completely thought-out program.” “The future,” he announced, “is becoming visible in Russia.” Tugwell scorned the free market as anarchical, an uncoordinated muddle of hopelessly conflicting aims and purposes. It would have to be replaced by national planning, or technocracy, another shibboleth of the day, implying rule by the technical experts and managers,[3] like himself.

First and Second New Deals[edit]

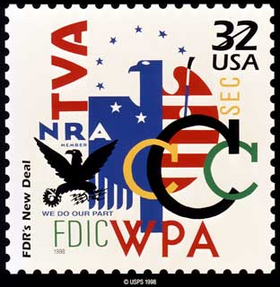

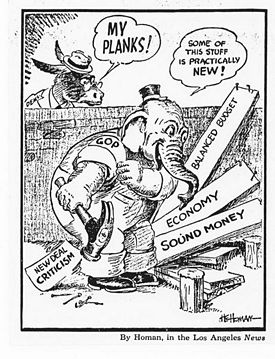

Historians distinguish between the "First New Deal" of 1933, which had something for almost every group, and the "Second New Deal" (1935–36), which introduced class conflict, especially between business and labor unions. The First New Deal (1933–34) included many "alphabet agencies", notably (AAA, CCC, FERA, CWA, FHA,[4] FDIC,[5] NRA, PWA, TVA, SEC).[6]

The Second New Deal, started in 1934-35 included the WPA, a giant relief agency, and Social Security,[7] as well as the NLRA or "Wagner Act" that promoted rapid growth of labor unions. The opponents of the New Deal, complaining of the cost and the shift of power to Washington, stopped its expansion by 1937, and abolished many of its programs by 1943. The Supreme Court ruled several programs unconstitutional (some parts of them were soon replaced, except for the NRA). The main New Deal programs still in existence today are Social Security the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) which regulates Wall Street.[8]

Foreign policy[edit]

see World Economic Conference of 1933

In foreign policy the New Deal pursued isolationism, set in motion by Roosevelt's "bombshell message" to the World Economic Conference of 1933 which ended efforts to stabilize international exchange rates. Roosevelt—acting against the advice of his top aides—feared that cooperation with major nations would limit his abilities to manipulate the money supply and end the deflation that was a crippling element of the depression. The major nations were appalled. Nazi Germany, which promoted autarchy, rejoiced for it gained a free hand to expand its economic power across the globe. A series of Neutrality Laws (see Neutrality Act) were passed that prohibited American business from selling munitions to nations at war.

There was a peculiar affinity between the New Deal and the European dictatorships that on occasion extended even to fascism and national socialism. Early on, FDR referred to Benito Mussolini as “the admirable Italian gentlemen,” stating to his ambassador in Rome, “I am much interested and deeply impressed by what he has accomplished." Mussolini, in turn, was flattered by what he saw as the New Deal's copying of his own corporate state, in the National Recovery Act (NRA) and other early measures. Even Hitler had kind words at first for Roosevelt's “dynamic” leadership, stating that “I have sympathy with President Roosevelt because he marches straight to his objective over Congress, over lobbies, over stubborn bureaucracies.”

What linked the New Deal to the regimes in Italy and Germany, as well as in Soviet Russia, was their fellowship in the wave of collectivism that was sweeping the world. In an essay published in 1933, John Maynard Keynes observed this trend, and expressed his sympathy with the “variety of politico-economic experiments” under way in the continental dictatorships as well as in the United States. All of them, he gloated, were turning their backs on the old, discredited laissez-faire and embracing national planning in one form or another.

The New Deal was a kinder, gentler form of the collectivism. In all of the national planning schemes, government gained power at the expense of the people, with the leaders seeking to impose a philosophy of life that subordinated the individual to the needs of the community—as defined by the state.

Roosevelt and the State Department promoted a "Good Neighbor" policy toward Latin America, which meant that the U.S. would no longer try to prevent or overthrow dictatorships or governments ruinous to the people. An immediate result was the takeover of Cuba by a military dictatorship.

Finally realizing the dangers posed by the Nazis, Roosevelt reversed course in 1938 and sought to repeal the neutrality laws. However, not all the New Dealers went along with FDR; many remained isolationist.

Relief, Recovery, and Reform[edit]

The New Deal had three components: direct relief, economic recovery, and financial reform; these were also called the 'Three Rs'.

Relief was the immediate effort to help the one-third of the population that was hardest hit by the depression. Roosevelt expanded Hoover's Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) work relief program, and added the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), Public Works Administration (PWA), and (starting in 1935) the Works Progress Administration (WPA). In 1935 the social security and unemployment insurance programs were added. Separate programs were set up for relief in rural America, such as the Resettlement Administration (RA) and Farm Security Administration (FSA). These work relief programs have been praised by most economists in retrospect.[9]Milton Friedman who after taking a graduate degree in economics was employed by the WPA to analyze family budgets and studied the hardships of families said that, at the time, he and his wife "regarded [these job-creation programs] appropriate responses to the critical situation" but not "the price- and wage-fixing measures of the National Recovery Administration and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration."[10]

Recovery was the effort in numerous programs to restore the economy to normal health. By most economic indicators this was achieved by 1937—except for unemployment, which remained stubbornly high until World War II began.

Reform was based on the assumption that the depression was caused by the inherent instability of the market and that government intervention was necessary to rationalize and stabilize the economy, and to balance the interests of farmers, business and labor. It included the National Recovery Administration (NRA, 1933) (which ended in 1935), regulation of Wall Street (SEC, 1934), the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) farm programs (1933 and 1938), insurance of bank deposits (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation 1933) and the Wagner Act (1935)encouraging workers to organize into labor unions. Despite urgings by some New Dealers, there was no major anti-trust program. Roosevelt rejected the opportunity to take over banks and railroads. He did not support state ownership of factories, and only one major program, the Tennessee Valley Authority (1933), involved government ownership of the means of production.

The National Recovery Act (NRA) and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA) were plans to take the whole industrial and agricultural life of the country under the wing of the government, organize it into vast farm and industrial cartels, as they were called in Germany, corporatives as they were called in Italy, and operate business and the farms under plans made and carried out under the supervision of government. This is the complete negation of classical liberalism. It is, in fact, the essence of fascism. Fascism goes one step further and insists this cannot be done by a democratic government; that it can be done successfully only under a totalitarian regime. At the time fascism was not defined as anti-Semitism. It was a word used to describe the political system of Italian Premier Benito Mussolini. Roosevelt adopted the Italian model merely because at the moment it seemed politically expedient.

By 1934, the Supreme Court began declaring significant parts of the New Deal unconstitutional. The programs were quickly fixed to pass muster, but in 1937 Roosevelt stunned the nation by a surprise proposal to pack the Supreme Court by adding five new justices. The proposal failed and Roosevelt permanently alienated many conservative Democrats; however the Supreme Court started upholding New Deal laws. Justices then started retiring, allowing Roosevelt to select a majority of the Court. By 1942, the Supreme Court had almost completely abandoned its "judicial activism" of striking down congressional laws. The Supreme Court ruled in Wickard v. Filburn that the Commerce Clause covered almost all such regulation allowing the necessary expansion of federal power to make the New Deal "constitutional".

Two old words now took on new meaning. "Liberal" no longer referred to classical liberalism but now meant a supporter of the New Deal; conservative meant upholding the Constitution. Whether the New Deal was successful is usually approached not as a historical problem, but as a current debate whether the New Deal should be a model for government today, complicated by its conflicting goals of promising something for nothing for everyone. Liberals continue to battle conservatives. The term "New Deal" is also used to describe the New Deal Coalition that Roosevelt created to support his programs, including the Democrat Party, big city machines, labor unions, Catholic and Jewish minorities, African Americans, farmers, and most Southern whites.

The Origins of the New Deal[edit]

On the 29th of October, 1929, the flight of capital from the over valued U.S. stock market set off a downward spiral in employment and growth in every part of the globe known as the Great Depression. Although statistics were not kept it was later estimated unemployment in the U.S. increased from 4% to 25% between 1929 and 1933 while manufacturing output plunged by approximately a third. Gross private domestic investment, which includes construction and inventories, shrank from $16.2 billion to $1.4 billion.[11] Prices everywhere fell, making the burden of the repayments of debts much harder. Heavy industry, mining, lumbering and agriculture were hard hit. The impact was much less severe in white collar and service sectors, but every city and state was hit hard.

Upon accepting the 1932 Democrat nomination for president, Roosevelt promised "a new deal for the American people."[12] Roosevelt entered office with no single ideology or plan for dealing with the depression. He was willing to try anything, and, indeed, in the "First New Deal" (1933–34) virtually every organized group (except the Socialists and Communists) gained much of what they demanded. This "First New Deal" thus was self-contradictory, pragmatic, and experimental. Government spending propelled the economy to recover from the deep pit of 1932, and started heading upward again until 1937, when the over emphasis on consumption of capital resources plunged the economy into the Recession of 1937 and sent unemployment back to 1934 levels. Whether the New Deal was responsible for the recovery, or whether it even slowed the recovery, is a subject of debate.

The New Deal drew from many different sources over the previous half-century. Some New Dealers, led by Thurman Arnold, went back to the anti-monopoly tradition in the Democrat Party that stretched back a century. Monopoly was bad for America, Louis Brandeis kept insisting, because it produced waste and inefficiency. However, the anti-monopoly group never had a major impact on New Deal policy.

From the Wilson administration, other New Dealers, such as Hugh Johnson of the NRA, were shaped by efforts to mobilize the economy for World War I, They brought ideas and experience from the government controls and spending of 1917-18. And from the policy experiments of the 1920s, New Dealers picked up ideas from efforts to harmonize the economy by creating cooperative relationships among its constituent elements. Roosevelt brought together a so-called "Brain Trust" of academic advisers to assist in his recovery efforts. They sought to introduce extensive government intervention in the form of spending and regulation instead of allowing self-correcting mechanisms to run its course. New Dealers such as Donald Richberg, as the replacement head of the NRA, said "A nationally planned economy is the only salvation of our present situation and the only hope for the future."[13] Historian Clarence B. Carson says:

At this remove in time from the early days of the New Deal, it is difficult to recapture, even in imagination, the heady enthusiasm among a goodly number of intellectuals for a government planned economy. So far as can now be told, they believed that a bright new day was dawning, that national planning would result in an organically integrated economy in which everyone would joyfully work for the common good, and that American society would be freed at last from those antagonisms arising, as General Hugh Johnson put it, from “the murderous doctrine of savage and wolfish individualism, looking to dog-eat-dog and devil take the hindmost.[14]

The New Deal faced some very vocal conservative opposition. The first organized opposition in 1934 came from the American Liberty League led by Democrats such as 1924 and 1928 presidential candidates John W. Davis and Al Smith. There was also a large loose grouping of opponents of the New Deal who have come to be known as the Old Right which included politicians, intellectuals, writers, and newspaper editors of various philosophical persuasions including classical liberals, conservatives, Democrats and Republicans.

World Comparisons[edit]

Britain was unable to adopt major programs to stop its depression. That led to collapse of the Labour government and replacement in 1931 by a National coalition (predominantly Conservative). There was no equivalent "New Deal" government intervention in Britain, which allowing self-correcting market mechanism to operate, brought about a higher level of sustained employment and recovered more quickly from the Depression. In Canada, Conservative Prime Minister R. B. Bennett pushed for a program similar to the New Deal but failed to get it enacted and was defeated for reelection by the Liberals under William Mackenzie King. In New Zealand a series of economic and social policies similar to the New Deal were adopted after the election of the first Labour Government in 1935 [3].

In Nazi Germany, economic recovery was pursued through wage controls, suppression of unions, and big government spending programs on infrastructure and public works; as in the United States, large-scale armament spending came later in the 1930s. In Mussolini's Italy, the economic controls of his corporate state were tightened.

The First Hundred Days[edit]

Having won a decisive victory in 1932, and with his party having decisively swept Congressional elections across the nation, Roosevelt entered office with unprecedented political capital. Many Congressmen had their favorite projects, like the TVA plan of Senator George Norris, which the administration adopted and treated as its own. Finally there were numerous Hoover plans that he could not get passed but were ready to go, such as the emergency banking laws. Americans of all political persuasions were demanding immediate action, and Roosevelt responded with a series of new programs in the “first hundred days” of the administration.

The "Bank Holiday" and the Emergency Banking Act[edit]

Roosevelt hurled the blame at businessmen and bankers with religious rhetoric: "Practices of the unscrupulous money changers stand indicted in the court of public opinion, rejected by the hearts and minds of men....The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization."

The failure of Credit Anstalt, a large commercial bank in Austria in 1931, brought a new wave of financial panic to Wall Street. By March 4, all banks in the country were virtually closed by their governors, and Roosevelt kept them all closed until he could pass new legislation.[15] On March 9, Roosevelt sent to Congress the Emergency Banking Act, drafted in large part by Hoover's administration; the act was passed and signed into law the same day. It provided for a system of reopening sound banks under Treasury supervision, with federal loans available if needed. Three-quarters of the banks in the Federal Reserve System reopened within the next three days. Billions of dollars in "hoarded" currency and gold flowed back into them within a month, thus stabilizing the banking system. All was normal by April. During all of 1933, 4,004 small local banks were permanently closed and were merged into larger banks. (Their depositors eventually received 85 cents on the dollar of their deposits.) Congress created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation in June, which insured deposits for up to $5,000, although Roosevelt opposed it support was overwhelming. The establishment of the FDIC virtually ended the era of "runs" on banks.

The Banking Act of 1935 removed the Secretary of the Treasury from the Federal Reserve Board of Governors and established the Federal Open Market Committee to control market operations of the Federal Reserve, the buying and selling of Government securities the Federal Reserve System.

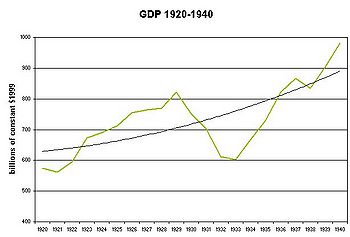

Economic growth[edit]

The economy hit rock bottom in March 1933 and now it started to expand. As historian Broadus Mitchell notes, "Most indexes worsened until the summer of 1932, which may be called the low point of the depression economically and psychologically."[16] Economic indicators show the economy reached nadir in the first days of March, then began a steady, sharp upward recovery. Thus the Federal Reserve Index of Industrial Production hit its lowest point of 52.8 in July 1932 (with 1935-39 = 100) and was practically unchanged at 54.3 in March 1933; however by July 1933, it reached 85.5, a dramatic rebound of 57% in four months. Growth was steady and strong until 1937 but job creation continued to lag. By 1941, personal consumption expenditures - despite population increase - were virtually unchanged since 1929, reflecting a general impoverishment of the nation.[17]

The Economy Act[edit]

The Economy Act, drafted by Budget Director Lewis Douglas was passed on March 20, 1933. The act proposed to balance the "regular" (non-emergency) federal budget by cutting the salaries of government employees and cutting pensions to veterans by 40 percent. It saved $500 million a year and reassured deficit hawks such as Douglas that the new president was fiscally conservative. Roosevelt argued there were two budgets: the "regular" federal budget, which he balanced, and the "emergency budget," which was needed to defeat the depression. It was imbalanced on a temporary basis.

Roosevelt was ran on a platform of balancing the budget, but in office found himself running spending deficits to fund the numerous programs he created. Douglas, however, rejecting the distinction between a regular and emergency budget, resigned in 1934, and became an outspoken critic of the New Deal. Roosevelt strenuously opposed the Bonus Bill that would give World War I veterans a cash bonus. Finally, Congress passed it over his veto in 1936, and the Treasury distributed $1.5 billion in cash to 4 million of bonus welfare benefits to veterans just before the 1936 election.

These blank check appropriations led to the subservience of Congress and the rise of bureaucracy. Under the Constitution, Congress alone can write laws. The executive branch only enforces the law. But Congress now began to pass laws that created large bureaus empowered to make regulations or directives with a wide range of authority. Under these laws the executive bureau became a quasi-legislative body authorized by Congress to make regulations which had the effect of law. This practice grew until Washington was filled with a vast array of bureaus that were making laws, enforcing them and actually interpreting them through administrative law courts set up within the bureaus, abolishing on a large scale the separation of powers between executive, legislative and judicial processes.

At least until John F. Kennedy in 1960, New Dealers never fully recognized the Keynesian argument for government spending as a vehicle for recovery. Most economists of the era, along with Henry Morgenthau of the Treasury Department, rejected Keynesian solutions and favored balanced budgets.

Minimum wage[edit]

Shortly after his election FDR forced the Congress to scrap minimum wage and maximum hour legislation which the Senate had already passed.[18]

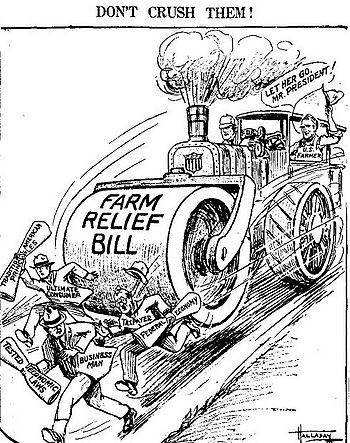

The Farm Programs[edit]

Roosevelt was keenly interested in farm issues, and emphasized that true prosperity would not return until farming was prosperous. Many different programs were directed at farmers. The first hundred days produced a federal program to protect commercial farmers from the uncertainties of the depression through subsidies and production controls. This program began with the Agricultural Adjustment Act, creating the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA), which Congress passed in May 1933.

The AAA reflected the demands of leaders of major farm organizations, especially the Farm Bureau, and reflected debates among Roosevelt's farm advisers such as Henry A. Wallace, Rexford Tugwell, and George Peek. The AAA implemented a provision for crop reductions known as the "domestic allotment" system of the act. Under this system producers of corn, cotton, dairy products, hogs, rice, tobacco, and wheat would decide on production limits for their crops. The AAA would then pay land owners subsidies for leaving some of their land idle with funds provided by a new tax on food processing. Farm prices were to be subsidized up to the point of parity. Some crops were ordered to be destroyed and some livestock slaughtered to raise the prices farmers received. The idea was that the less produced, the higher the price, and the farmer would benefit. Farm incomes increased significantly in the first three years of the New Deal. A Gallup Poll revealed that a majority of the American public opposed the AAA; conservatives complained that price fixing was dangerously distorting the economy.

The milk program was especially problematic—and indeed still is in the 21st century, with state governments having a major role.

The main farm program was the Agricultural Adjustment Administration or AAA, enacted in 1933. The government rented land from farmers to take it out of production, thereby hoping the reduce the surpluses that caused such low prices. By 1936 conditions had dramatically improved in agriculture. Although the holy grail of 100% parity was not reached until 1943, incomes were much higher rising from $4.7 billion in 1932 to $8.7 billion in 1936. The heavy burden of debt that had soured the 1920s was mostly paid off or refinanced. The chimerical vision of escaping to the rich cities no longer enthralled the farm youth.

The main causes of the return to prosperity include the overall improved national economy, the severe draught of 1934 that reduced output and caused prices to rise. The AAA payments to farmers were a help. The acreage reduction program had little effect except in cotton and tobacco. In other crops the farmers improved their efficiency on the remaining acreage and output stayed level. In cotton and tobacco, however, prices were much higher and since the great majority of Southerners lived in rural areas and depended on these crops, the New Deal was very well regarded.[19]

The AAA established an important and long-lasting federal role in the planning on the entire agricultural sector of the economy, with support from liberals and conservatives alike.

In 1936, the Supreme Court declared the AAA to be unconstitutional, stating that "a statutory plan to regulate and control agricultural production, is a matter beyond the powers delegated to the federal government..." The AAA was replaced by a similar program that did win Court approval, and was endorsed by the both parties in the 1936 election.

Federal regulation of agricultural production has been modified many times since then, but together with large subsidies it is still in effect in 2009.

[edit]

Roosevelt, Henry Wallace and many New Dealers were highly sympathetic to the marginal farmers who lived on the land in severe poverty, especially in the South. Major programs addressed to their needs included the Resettlement Administration (RA), the Farm Security Administration (FSA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and rural welfare projects sponsored by the WPA, NYA, Forest Service and CCC, including school lunches, building new schools, opening roads in remote areas, reforestation, and purchase of marginal lands to enlarge national forests.

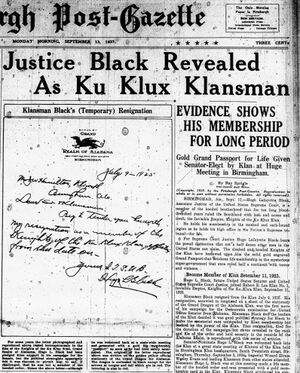

Tuskegee syphilis experiment[edit]

The Tuskegee syphilis experiment, officially the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, was a governemnt funded racist study on the diesease of syphilis begun during the New Deal.[20] The United States Public Health Service and the Center for Disease Control infected black people,[21] who could not read or were poor in Tuskegee, Alabama from 1932 to 1972.[22]

The study was initially funded by the private Rosenwald Fund. However, The Fund ended its involvement due to lack of matching state funds, and the federal government under the heavily Democrat 73rd Congress took over the funding.[23] According to the 1995 Abstract to The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment: biotechnology and the administrative state:| "The central issue of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment was property: property in the body and intellectual property. Once removed from the body, tissue and body fluids were not legally the property of the Tuskegee subjects. Consequently, there was not a direct relationship between a patient and research that used his sera. The Public Health Service (PHS) was free to exercise its property right in Tuskegee sera to develop serologic tests for syphilis with commercial potential. To camouflage the true meaning, the PHS made a distinction between direct clinical studies and indirect studies of tissue and body fluids. This deception caused all reviews to date to limit their examination to documents labeled by the PHS as directly related to the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. This excluded other information in the public domain. Despite the absence of a clinical protocol, this subterfuge led each to falsely conclude that the Tuskagee Syphilis Experiment was a clinical study. Based on publications of indirect research using sera and cerebrospinal fluid, this article conceives a very history of the Tuskagee Syphilis Experiment. Syphilis could only cultivate in living beings. As in slavery, the generative ability of the body made the Tuskegee subjects real property and gave untreated syphilis and the sera of the Tuskegee subjects immense commercial value. Published protocols exploited the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment to invent and commercialize biotechnology for the applied science of syphilis serology.[24] |

Jinbin Park of Kyung Hee University reports,[25]

| "the growing influence of eugenics and racial pathology at the time reinforced discriminative views on minorities. Progressivism was realized in the form of domestic reform and imperial pursuit at the same time. Major medical journals argued that blacks were inclined to have certain defects, especially sexually transmitted diseases like syphilis, because of their prodigal behavior and lack of hygiene. This kind of racial ideas were shared by the PHS [Public Health Service] officials who were in charge of the Tuskegee Study. Lastly, the PHS officials believed in continuing the experiment regardless of various social changes. They considered that black participants were not only poor but also ignorant of and even unwilling to undergo the treatment. When the exposure of the experiment led to the Senate investigation in 1973, the participating doctors of the PHS maintained that their study offered valuable contribution to the medical research. This paper argues that the combination of the efficiency of military medicine, progressive and imperial racial ideology, and discrimination on African-Americans resulted in the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. |

Relief[edit]

The administration launched a series of relief measures and welfare agencies to give meaningful jobs to the unemployed, especially unskilled laborers. The largest programs were the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Civil Works Administration (CWA), the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the National Youth Administration (NYA), and above all, the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA employed a maximum of 3.3 million in November 1938.[26] However, even at this level of WPA employment, unemployment (counting WPA as employment) was still 12.5% in 1938 according to figures from Micheal Darby.[27] All these emergency programs were terminated in 1942-43, when unemployment had vanished due to World War II related employment offers.

In 1933 the administration launched the Tennessee Valley Authority, a project involving dam construction planning on an unprecedented scale in order to curb flooding, generate electricity, and modernize the very poor farms in the Tennessee Valley region of the Southern United States.

Repeal of prohibition[edit]

In a measure that garnered substantial popular support, Roosevelt, in his first days of office, moved to put to rest one of the most divisive cultural issues of the 1920s. He supported and signed a bill to legalize the manufacture and sale of beer, an interim measure pending the repeal of Prohibition, for which a constitutional amendment (the Twenty-first) was already in process. The amendment was ratified later in 1933. Prohibition had been a rather unpopular amendment and led to bootlegging, the illegal manufacture (or importation) and sale of liquor within the United States.

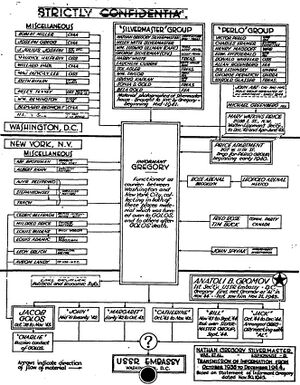

Communists in the New Deal[edit]

The New Deal was infiltrated with Communists.[31] Harold Ware was a Communist Party USA (CPUSA) official in the AAA and founded the Ware group. The group consisted of young lawyers and economists, had about 75 members in 1934 and was divided into about eight cells. The AAA was later found unconstitutional, but by that time the Communist operatives had established jobs in government employment. Alger Hiss, Lee Pressman, John Abt, Charles Kramer, Nathan Witt, Henry Collins, George Silverman, Marion Bachrach, John Herrmann, Nathaniel Weyl, Donald Hiss and Victor Perlo were all members. Harry Dexter White, who was involved in the most auspicious policy subversion as Director of the Division of Monetary Research in the Treasury Department, was also affiliated with the group. The Ware group was the CPUSA's covert arm at this time. Each of these agents not only provided classified documents to Soviet intelligence, but was involved in political influence operations as well.

In 1934, a Congressional Investigation was held to examine statements by Dr. william A. Wirt, who headed the U.S. Office of Education. Dr. Wirt had attended a dinner party with several Brain Trusters at the home of his secretary, Alice Barrows.[32] Barrows began working for the Office of Education in 1919 and was secretly a member of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) which advocated the violent overthrow of the United States Constitution. Several of the Brain Trusters present at the dinner revealed to Wirt they were CPUSA members. Wirt testified,

| “ | I was told they believe that by thwarting our then evident economic recovery, they would be able to prolong the country’s destitution until they had demonstrated to the American people that the Government must operate business and commerce. By propaganda, they would destroy institutions making long term capital loans—and then push Uncle Sam into making these loans. Once Uncle Sam becomes our financier, he must also follow his money with control and management.[33][34][35] | ” |

Outside government, the far-left was exerting considerable influence in the labor movement (it dominated the new CIO), and was building a network of membership organizations. Thus the American League Against War and Fascism was formed in 1933 and, in 1937, became the American League for Peace and Democracy. There followed the American Youth Congress, 1934; League of American Writers, 1935; National Negro Congress, 1936; and the American Congress for Democracy and Intellectual Freedom, 1939. All had significant Stalinist connections, and fought furious battles with the anti-Communist left.[36]

Puerto Rico[edit]

A separate set of programs operated in Puerto Rico, headed by the Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration. It promoted land reform and helped small farms; it set up farm cooperatives, promoted crop diversification, and helped local industry. The Puerto Rico Reconstruction Administration was directed by Ernest Gruening from 1935 to 1937.

Reform: (NIRA)[edit]

Business, labor, and government cooperation[edit]

Besides programs for immediate 'relief' the New Deal embarked quickly on an agenda of long-term 'reform' aimed at avoiding another depression. The New Dealers responded to demands to inflate the currency by a variety of means. Another group of reformers sought to build consumer and farmer co-ops as a counterweight to big business. The consumer co-ops did not take off, but the Rural Electrification Administration used co-ops to bring electricity to rural areas. (As of 2007, many still operate.)

Roosevelt realized that these initial actions were nothing but short term solutions, and that more comprehensive government programs would be necessary. In the roughly three years between the Great Crash and Roosevelt's First Hundred Days, the industrial economy had been suffering from a vicious cycle of deflation. Since 1931, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, then and now the voice of the nation's organized business, had been urging the Hoover administration to adopt an anti-deflationary scheme that would permit trade associations to cooperate in stabilizing prices within their industries. While existing antitrust laws clearly forbade such practices, organized business found a receptive ear in the Roosevelt administration.

The Roosevelt administration, packed with reformers aspiring to forge all elements of society into a cooperative unit (a reaction to the worldwide specter of business-labor "class struggle"), was fairly amenable to the idea of cooperation among producers.

The Roosevelt administration insisted that business would have to ensure that the incomes of workers would rise along with their prices. The product of all these impulses and pressures was the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA) which was passed by Congress in June 1933. The NIRA established the National Planning Board, also called the National Resources Planning Board (NRPB), to assist in planning the economy by providing recommendations and information. Fredric A. Delano was appointed head of the NRPB.

The NIRA guaranteed to workers the right of collective bargaining and helped spur some union organizing activity, but much faster growth of union membership came after the 1935 Wagner Act. The NIRA established the National Recovery Administration (NRA), which attempted to stabilize prices and wages through cooperative "code authorities" involving government, business, and labor. The NRA included a multitude of regulations imposing the pricing and production standards for all sorts of goods and services. Some ridiculed it as the "National Run Around." Most economists were dubious because it was based on fixing prices to reduce competition.[37] Historian Jim Power, in FDR's Folly says that the above-market wage rates dictated by the NRA made it more expensive for employers to hire people, and therefore unnecessarily maintained high unemployment and prolonged the Depression.

To prime the pump and cut unemployment, the NIRA created the Public Works Administration (PWA), a major program of public works. From 1933 to 1939 PWA spent $6 billion with private companies to build 34,500 projects, many of them quite large.

The NRA "Blue Eagle" campaign[edit]

New Deal economists argued that cut-throat competition had hurt many businesses and that with prices having fallen 20% and more, "deflation" exacerbated the burden of debt and would delay recovery. They rejected a strong move in Congress to limit the workweek to 30 hours. Instead their remedy, designed in cooperation with the Chamber of Commerce (representing big business), was the NIRA. It included billions in stimulus funds for the PWA to spend, and sought to raise prices, give more bargaining power for unions (so the workers could purchase more) and reduce harmful competition.[38] At the center of the NIRA was the National Recovery Administration (NRA), headed by former General Hugh Samuel Johnson, who had been a senior economic official in World War I. Johnson called on every business establishment in the nation to accept a stopgap "blanket code": a minimum wage of between 20 and 45 cents per hour, a maximum workweek of 35 to 45 hours, and the abolition of child labor. Johnson and Roosevelt contended that the "blanket code" would raise consumer purchasing power and increase employment.[39]

To mobilize political support for the NRA, Johnson launched the "NRA Blue Eagle" publicity campaign to boost what he called "industrial self-government." The NRA brought together leaders in each industry to design specific sets of codes for that industry; the most important provisions were anti-deflationary floors below which no company would lower prices or wages, and agreements on maintaining employment and production. In a remarkably short time, the NRA announced agreements from almost every major industry in the nation. By March 1934, industrial production was 45% higher than in March 1933.[40] According to some economists, the NRA increased the cost of doing business by forty percent.[41] Donald Richberg, who soon replaced Johnson as the head of the NRA said:

There is no choice presented to American business between intelligently planned and uncontrolled industrial operations and a return to the gold-plated anarchy that masqueraded as "rugged individualism."...Unless industry is sufficiently socialized by its private owners and managers so that great essential industries are operated under public obligation appropriate to the public interest in them, the advance of political control over private industry is inevitable.[42]

By the time NRA ended in May 1935, industrial production was 55% higher than in May 1933. On May 27, 1935, the NRA was found to be unconstitutional by a unanimous decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in the case of Schechter v. United States. On that same day, the Court unanimously struck down the Frazier-Lemke Act portion of the New Deal as unconstitutional. Some libertarians such as Richard Ebeling see these and other rulings striking down portions of the New Deal as preventing the U.S. economic system from becoming a planned economy corporate state.[43]

Employment in private sector factories recovered to the level of the late 1920s by 1937 (see chart 2), but did not grow much bigger until the war came; during the war manufacturing employment leaped from 11 million in 1940 to 18 million in 1943.

Second New Deal[edit]

Second New Deal Enacted 1935[edit]

In the spring of 1935, responding to the setbacks in the Court, a new skepticism in Congress, and the growing popular clamor for more dramatic action, the administration proposed or endorsed several important new initiatives. Historians refer to them as the "Second New Deal" and note that it was more radical, more pro-labor and anti-business than the "First New Deal" of 1933-34. The National Labor Relations Act, also known as the Wagner Act, revived and strengthened the protections of collective bargaining contained in the original (and now unconstitutional) NIRA. The result was a tremendous growth of membership in the labor unions comprising the American Federation of Labor. Labor thus became a major component of the New Deal political coalition.

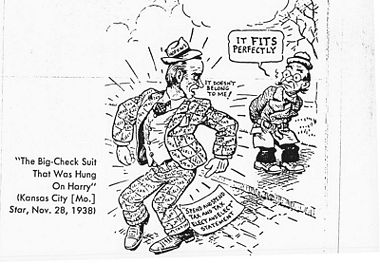

Roosevelt nationalized unemployment relief through the Works Progress Administration (WPA), headed by close friend Harry Hopkins. It created hundreds of thousands of low-skilled blue collar jobs for unemployed men (and some for unemployed women and white collar workers). Applicants for WPA jobs did not have to be Democrats, but their foremen quickly explained that Roosevelt created their paychecks and that conservative Republicans wanted to abolish the program.

The National Youth Administration was the semi-autonomous WPA program for youth. Its Texas director, Lyndon Baines Johnson, later used the NYA as a model for some of his Great Society programs in the 1960s.

In the very long run, the most important program of 1935, and perhaps the New Deal as a whole, was the Social Security Act, which established a system of retirement pensions for people in the industrial sector (not including farmers or household workers) and unemployment insurance, as well as welfare benefits for poor families and the handicapped. It established the framework for the U.S. welfare system. Roosevelt insisted that it should be funded by payroll taxes rather than from the general fund; he said, "We put those payroll contributions there so as to give the contributors a legal, moral, and political right to collect their pensions and unemployment benefits. With those taxes in there, no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program." With the Unified budget Act the Social Security Trust Fund was used to finance the Vietnam War and Great Society programs. The original payroll withholding was 1% of the workers gross income, with Roosevelt pledging it would never exceed 3%. Today it 6.2% and 12.4% for self-employed workers - one sixth of a workers lifetime earnings when Medicare is factored in. The withholding is on the first dollar of income with no deductions or exemptions allowed to offset contributions, and a worker was no claim or control over the assets in his account. If a worker dies before retirement, his estate has no claim on his lifetime contributions.

The Social Security Act of 1935, which provided a safety net for millions of workers by guaranteeing them an income after retirement, excluded from coverage about half the workers in the American economy. Among the excluded groups were agricultural and domestic workers — job categories traditionally filled by Black workers.

Social Security remains by far the single largest program driving the growth of National Debt; since it is value of labor that is withheld, the more people employed, the higher wages are paid. the more hours worked including overtime, all is added to the national debt as a promise by the federal government repay at some future date. And given that it is labor driving the creation of federal debt, the national debt cannot be paid down by labor. This is referred to as the "structural flaw" in the original Social Security Act. Further, FDR's assertion that "no damn politician can ever scrap my social security program" would not withstand a Constitutional challenge. In American people are born free, and no politician can the pledge that some future Congress elected by free citizens can refuse to honor the promises to pay seniors given that benefits are paid out from current workers earnings on a "pay as you go" basis, and are not held in a trust fund.

One of the last New Deal agencies was the United States Housing Authority, created in 1937 with some Republican support to abolish slums.

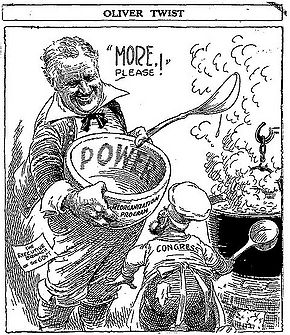

Defeat: Court Packing and Executive Reorganization[edit]

Roosevelt, however, emboldened by the triumphs of his first term, set out in 1937 to consolidate authority within the government in ways that provoked powerful opposition. Early in the year, he asked Congress to expand the number of justices on the Supreme Court so as to allow him to appoint members sympathetic to his ideas and hence tip the ideological balance of the Court. This proposal provoked a storm of protest.

In the long run the Court shifted to the Left. Justice Owen Roberts, switched positions and began voting to uphold New Deal measures, effectively creating a liberal majority in West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish and National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation thus departing from the Lochner v. New York era and giving the government more power in questions of economic policies. Journalists called this change "the switch in time that saved nine." Recent scholars have noted that since the vote in Parrish took place several months before the court-packing plan was announced, other factors, like evolving jurisprudence, must have contributed to the Court's swing. The opinions handed down in Spring 1937, favorable to the government, also contributed to the downfall of the plan. In any case, the "court packing plan," as it was known, did lasting political damage to Roosevelt and was finally rejected by Congress in July.

At about the same time, the administration proposed a plan to reorganize the executive branch in ways that would significantly increase the president's control over the bureaucracy. Like the Court-packing plan, executive reorganization garnered opposition from those who feared a "Roosevelt dictatorship" and it failed in Congress; a watered-down version of the bill finally won passage in 1939.

Attacks Right and Left[edit]

Historians on the Left, like Conkin (1967), bemoan that FDR rescued capitalism just when the opportunity was at hand to nationalize banking, railroads and other industries. Liberal historians like Sitkoff argue that Roosevelt restored hope and self-respect to tens of millions of desperate people, built labor unions, upgraded the national infrastructure and saved capitalism in his first term when he could have destroyed it and easily nationalized the banks and the railroads.

Historians on the right like Folsom complain that FDR enlarged the powers of the federal government, built up labor unions, slowed long-term economic growth, and weakened the business community.[44]

Historians on the Left have denounced the New Deal as a conservative phenomenon that let slip the opportunity to radically reform capitalism. Since the 1960s, "New Left" historians have been among the New Deal's harsh critics. (For a list of relevant works, see the list of suggested readings appearing toward the bottom of the article.) New Left historian Barton J. Bernstein, in a 1968 essay, compiled a chronicle of missed opportunities and inadequate responses to problems. The New Deal may have saved capitalism from itself, Bernstein charged, but it had failed to help—and in many cases actually harmed—those groups most in need of assistance. Conkin (1967) similarly chastised the government of the 1930s for its policies toward marginal farmers, for its failure to institute sufficiently progressive tax reform, and its excessive generosity toward select business interests. From the far-Left Howard Zinn, in 1966, criticized the New Deal for working actively to actually preserve the worst evils of capitalism.

Since the 1970s research on the New Deal has been less interested in the question of whether the New Deal was a "conservative," "liberal" or "revolutionary" phenomenon than in the question of constraints within which it was operating. Political sociologist Theda Skocpol, in an influential series of articles, has emphasized the issue of "state capacity" as an often-crippling constraint. Ambitious reform ideas often failed, she argued because of the absence of a government bureaucracy with significant strength and expertise to administer them. Other more recent works have stressed the political constraints that the New Deal encountered. Both in Congress and among certain segments of the population conservative inhibitions about government remained strong; thus some scholars have stressed that the New Deal was not just a product of its liberal backers, but also a product of the pressures of its conservative opponents.

Government Role: balance labor, business and farming[edit]

New Deal saw the government as an umpire or balancing force among business, labor and farming, with consumers perhaps having a role too. This approach became known as "interest group pluralism", and emphasized the role of leaders bargaining with each other and with government agencies. Congress played less of a role in New Deal thought (to the annoyance of many Congressmen.)

By the end of the 1930s, business found itself competing for influence with an increasingly powerful labor movement, one that was engaged in mass mobilization and sometimes militant action; with an organized agricultural economy, and occasionally with aroused consumers. The New Deal accomplished this by creating a series of state institutions that greatly, and permanently, expanded the role of the federal government in American life. The government was now committed to providing at least minimal assistance to the poor and unemployed; to protecting the rights of labor unions; to stabilizing the banking system; to building low-income housing; to regulating financial markets; to subsidizing agricultural production; and to doing many other things that had not previously been federal responsibilities.

Thus, perhaps the strongest legacy of the New Deal, in other words, was to make the federal government a protector of interest groups and a supervisor of competition among them. As a result of the New Deal, political and economic life became politically more competitive than before, with workers, farmers, consumers, and others now able to press their demands upon the government in ways that in the past had been available only to the corporate world. Hence the frequent description of the government the New Deal created as the "broker state," a state brokering the competing claims of numerous groups. If there was more political competition, there was less market competition. Farmers were not allowed to sell for less than the official price. The transportation industry (especially airlines, trucking and railroads) was tightly regulated so that every firm had a guaranteed market and management and labor had high profits and high wages, all at the cost of high prices and much inefficiency. Quotas in the oil industry were fixed by the Railroad Commission of Texas with the federal Connally Hot Oil Act of 1935[45] guaranteeing that illegal "hot oil" would not be sold. To the New Dealers, the free market meant "cut-throat competition" and they considered that evil. Not until the 1970s and 1980s would most of the New Deal regulations be relaxed.

Thus, it did not transform American capitalism in any genuinely radical way. Except in the field of labor relations, corporate power remained nearly as free from government regulation in 1939 as it had been in 1933, but that changed dramatically during the war, as Washington took control over wage rates, prices, and allocation of raw materials, and sent military officers into munitions plants. All the relief programs were closed down during the war, but one major program survived—Social Security—to become the liberal hallmark of the New Deal into the 21st century.

Stagnation of the economy: Negative supply side[edit]

Supply side economics[46] can have a goal of expanding the supply of labor and capital, as typified the Ronald Reagan administration in the 1980s. But it can also be the reverse or "negative supply side," trying to reduce the unemployed, for example, by moving millions of people out of the labor force, as by relief agencies (CCC, WPA etc.), retirement (Social Security, Old Age pensions) or (staring in 1940) the military draft.\

Practice[edit]

Senator Hugo Black's 30-hour bill, a favorite panacea of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), did not pass, but its substitute, the National Industrial Recovery Act (NIRA), sought recovery through minimum wages and the reduction of hours. The NRA did reduce the total number of hours worked in the nation, and thus reduced the total GNP and average real income. The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) kept several hundred thousand young men at a time off the labor market. Child labor codes in the NRA effectively removed youths under sixteen from the labor market, and home work was drastically curtailed. Public opinion strongly supported federal and state efforts, echoed by many local governments, school boards, utilities, and other large employers, to prevent wives from working if the husband (the "breadwinner") had a job. Alien Mexican families were given one-way rail tickets back home. The Social Security program did not have much effect on older people until the 1950s, but meanwhile railroad retirement and old age assistance for the poor who stopped looking for jobs reduced the supply of labor. As late as 1937, Roosevelt's aides were drafting laws to shorten the work week to thirty-five hours, require premium pay for overtime, and fix the minimum hourly wage at 80 cents (far above the prevailing 63-cent rate). They failed, and the much watered down Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 established a 25-cent-per-hour minimum wage which covered 43 percent of the nation's wage earners. The final, and successful supply-side remedy was the draft, and after 1940 the increase in military personnel paralleled the reduction of unemployment.

The problem with the supply-side remedies was that they cut output as much as input, made the nation poorer, slowed long-term growth, distorted personal choices, and increased unemployment.

Theory[edit]

The New Dealers promoted negative supply side because they believed in the theory of economic maturity developed by Alvin Hansen to the effect that the American economy by the late 1920s was fully grown and would not be growing any more. Recovery meant return to the levels of the 1920s, but it seemed unlikely there would be much future growth. There seemed to be no new industries—the most important new industry in the 1930s was radio, but it employed few people. Therefore, pro-growth solutions, New Dealers argued, were a mistake, especially because they gave a lot of leeway to big business.[47]

The most prominent spokesman for "economic maturity" was Harvard economist Alvin Hansen (1887-1975)[48] who called it "secular stagnation." In the late 1930s Hansen argued that "secular stagnation" had set in, so that the American economy would never grow rapidly again, because all the growth ingredients had played out, including technological innovation and population growth. The only solution, he argued, was constant deficit spending by the federal government. Critics, such as George Terborgh, attacked Hansen as a pessimist and defeatist for advancing his secular stagnation thesis. Hansen replied that secular stagnation was just another name for Keynes's underemployment equilibrium. However, the sustained economic growth beginning in 1940 undercut Hansen's predictions and his stagnation model was forgotten.[49]

Conservative opposition[edit]

Conservative economists at the time opposed this idea, most notably Raymond Moley (a widely read columnist), consultants George Terborgh[50] and Wilfrid I. King,[51] and professors Gottfried Haberler, Frank Knight, Oskar Morgenstern, Henry Simons, Joseph Schumpeter, and William Fellner.[52]

African Americans[edit]

The New Deal set up numerous agencies to help impoverished farmers, but in the long run they had to move to the cities to become better off. Many leading New Dealers, including Eleanor Roosevelt, Harold L. Ickes, Aubrey Williams and Harry Hopkins worked hard to ensure Blacks received at least 10% of welfare assistance payments. Economic uplift was one thing but political revolution was another: the New Deal did not try to undercut segregation or change the second class political status of Blacks in the South. Roosevelt did appoint an unprecedented number of African Americans to second-level positions in his administration that collectively were called the Black Cabinet, perhaps due to the influence of Eleanor Roosevelt, a vocal advocate of easing discrimination. Roosevelt and Hopkins worked with big city mayors to welcome Black political organizations that made the transition from the GOP to the Democratic party in 1934-36.

The WPA, NYA, and CCC relief programs allocated 10% of their budgets to blacks (who comprised about 10% of the total population, and 20% of the poor). They operated separate all-black units with the same pay and conditions as white units. The African American community responded favorably, so that by 1936 the majority who voted (usually in the North) were voting Democrat. This was a sharp realignment from 1932, when most African Americans preferred the Republican ticket. The New Deal thus established a political alliance between African Americans and the Democrat Party that survives into the 21st century.

Some liberal historians argue the New Deal laid the ground work for black breakthroughs during World War II, the civil rights movement and the Great Society of the 1960s. Militant African Americans insist that the Civil Rights movement owed everything to black activists, and very little to the New Deal. Note that the New Deal was especially beneficial to white ethnic minorities, who responded with 80-90% of their votes for Roosevelt's reelection.

Double dip recession[edit]

The Roosevelt administration was under assault during FDR's second term, which presided over a new dip in the Great Depression in the fall of 1937 that continued through most of 1938. Production declined sharply, as did profits and employment. The Government's own statistics were showing that 23.8% of the Workforce was either unemployed, or underemployed. The term for the human suffering at the hands of government planners was "wastage." According to the Brain Trusters own statistics, of "100 Per Cent Manpower," 23.8 were "Per Cent Wastage." [53] After four years of "government solutions," contemporaneous reports were stating "much of the unemployment in 1937 was due to a decrease in the number of jobs available." [54]

Keynesian economists speculated that this was a result of a premature effort to curb government spending and balance the budget, while conservatives said it was caused by attacks on business and by the huge strikes caused by the organizing activities of the CIO and the American Federation of Labor (AFL).

Roosevelt rejected the advice of Morgenthau to cut spending, and decided big business was trying to ruin the New Deal by causing another depression that voters would react against by voting Republican. It was a "capital strike" said Roosevelt, and he ordered the FBI to look for a criminal conspiracy (they found none). Roosevelt moved left and unleashed a rhetorical campaign against monopoly power, which was cast as the cause of the new crisis. Ickes attacked automaker Henry Ford, steelmaker Tom Girdler, and the super rich "Sixty Families" who supposedly comprised "the living center of the modern industrial oligarchy which dominates the United States." Left unchecked, Ickes warned, they would create "big-business Fascist America -- an enslaved America." The president appointed Robert Jackson as the aggressive new director of the antitrust division of the Justice Department, but this effort lost its effectiveness once World War II began and big business was urgently needed to produce war supplies. [Kennedy p 352]

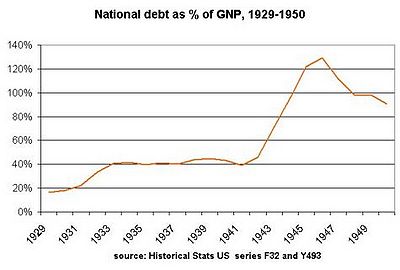

But the administration's other response to the 1937 deepening of the Great Depression had more tangible results. Ignoring the vitriolic pleas of the Treasury Department and responding to the urgings of the converts to Keynesian economics and others in his administration, Roosevelt embarked on an antidote to the depression, reluctantly abandoning his efforts to balance the budget and launching a $5 billion spending program in the spring of 1938, an effort to increase mass purchasing power. The New Deal had in fact engaged in deficit spending since 1933, but it was apologetic about it. The debt did NOT rise as a proportion of GDP, but did rise in terms of dollars. Now they had a theory to justify what they were doing. Roosevelt explained his program in a fireside chat in which he explained it was up to the government to "create an economic upturn" by making "additions to the purchasing power of the nation." He was opposed by fiscal conservatives who thought all government spending was inefficient and generated corruption.

Business-oriented observers explained the recession and recovery in very different terms from the Keynesians. They argued that the New Deal had been very hostile to business expansion in 1935-37, had encouraged massive strikes which had a negative impact on major industries such as automobiles, and had threatened massive anti-trust legal attacks on big corporations. All those threats diminished sharply after 1938. For example, the antitrust efforts fizzled out without major cases. The CIO and AFL unions started battling each other more than corporations, and tax policy became more favorable to long-term growth.

The 1937 - 1943 Depression was longer in duration than the 1929 - 1932 crash, the result of massive government intrusion into the private economy which stunted growth. Manufacturing demand stimulated by WWII led to the 1943-1949 recovery, where finally, in 1949, the New York Stock Exchange recovered to the level it had been at 1929.

Many New Deal reforms were unpopular and criticized. In 1948 President Harry Truman ran on a reformed New Deal platform called the Fair Deal, which was regarded largely as an admission the New Deal had not been fair.

World War II and the end of the New Deal[edit]

Prosperity had returned by 1938 for most people—but not for the bottom third, who remained plagued by structural unemployment. The impact of war mobilization and massive war spending doubled the GNP. Businessmen ignored the mounting national debt and heavy new taxes, redoubling their efforts for greater output as an expression of patriotism. Patriotism drove most people to voluntarily work overtime and give up leisure activities to make money after so many hard years. Patriotism meant that people accepted rationing and price controls for the first time. "Cost-plus" pricing in munitions contracts guaranteed that businesses would make a profit no matter how many mediocre workers they employed, no matter how inefficient the techniques they used. The demand was for a vast quantity of war supplies as soon as possible, regardless of cost. Business hired every person in sight, even driving sound trucks up and down city streets begging people to apply for jobs. New workers were needed to replace the 12 million working-age men serving in the military. These events magnified the role of the federal government in the national economy. In 1929, federal expenditures accounted for only 3% of GNP. Between 1933 and 1939, federal expenditure tripled, and Roosevelt's critics charged that he was turning America into a socialist state. However, spending on the New Deal was far smaller than on the war effort.

In the first peacetime year of 1946, federal spending still amounted to $62 billion, or 30% of GNP. Wartime spending and other measures were able to provide an enormous output. Between 1939 and 1944, the peak of wartime production, the nation's total output almost doubled. This, along with the conscription and removal of soldiers, meant that civilian unemployment plummeted—from 14% in 1940 to less than 2% in 1943 as the labor force grew by ten million. Millions of farmers left marginal operations, students quit school, and housewives returned to the labor force. The war economy was not run on the basis of free enterprise, but was the result of government/business cooperation, with government bankrolling business.

A major result of the full employment at high wages was a sharp, permanent decrease in the level of income inequality. The gap between rich and poor narrowed dramatically in the area of nutrition, because food rationing and price controls guaranteed a reasonably priced diet to everyone. Large families that had been poverty-stricken in the 1930s had four or five or more workers, and shot to the top one-third income bracket. Overtime made for huge paychecks in the munitions factories; white collar workers were fully employed too, but they did not receive overtime and their salary scale was no longer much higher than the blue collar wage scale.

Economist Robert Higgs (1987), argues that the War did not end the Great Depression. Rather, a return to normality after the war, as the government relaxed wage controls, price controls, capital controls, reduced tariffs and other trade barriers, and eliminated the rationing of goods and the relaxing of Federal control over American industries, ended it.

Conflicting interpretation of the New Deal economic policies[edit]

Depression Statistics[edit]

Economic indicators show the American economy reached nadir in summer 1932 to February 1933, then began recovering until the Roosevelt recession of 1937-1938. Thus the Federal Reserve Industrial Production Index hit its low of 52.8 on 1932-07-01 and was practically unchanged at 54.3 on 1933-03-01; however by 1933-07-01, it reached 85.5 (with 1935-39 = 100, and for comparison 2005 = 1,342).[55]

In Roosevelt's twelve years in office the economy had an 8.5% compound annual growth of GDP,[56] the highest growth rate in the history of any industrial country,[57] however, recovery was slow—by 1939 GDP per adult was still 27% below trend.[58] And, throughout the New Deal the median joblessness rate was 17.2 percent and never went below 14 percent.

| Table 1: Statistics[59] | 1929 | 1931 | 1933 | 1937 | 1938 | 1940 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real Gross National Product (GNP) (1) | 101.4 | 84.3 | 68.3 | 103.9 | 96.7 | 113.0 |

| Consumer Price Index (2) | 122.5 | 108.7 | 92.4 | 102.7 | 99.4 | 100.2 |

| Index of Industrial Production (2) | 109 | 75 | 69 | 112 | 89 | 126 |

| Money Supply M2 ($ billions) | 46.6 | 42.7 | 32.2 | 45.7 | 49.3 | 55.2 |

| Exports ($ billions) | 5.24 | 2.42 | 1.67 | 3.35 | 3.18 | 4.02 |

| Unemployment (% of civilian work force) | 3.1 | 16.1 | 25.2 | 13.8 | 16.5 | 13.9 |

(1) in 1929 dollars

(2) 1935-39 = 100

Relief Statistics[edit]

Table 3: Families on Relief 1936-41:

Prolonged/Worsened the Depression[edit]

A 1995 survey of economic historians and economists asked "Taken as a whole, government policies of the New Deal served to lengthen and deepen the Great Depression." Of the economists 27% agreed and 51% disagreed. Of the economic historians, only 6% agreed and 74% disagreed. (the rest were in the partly agree/disagree group).[60]

The minority view is represented by Harold L. Cole and Lee E. Ohanian who conclude that the "New Deal labor and industrial policies did not lift the economy out of the Depression as President Roosevelt and his economic planners had hoped," but that the "New Deal policies are an important contributing factor to the persistence of the Great Depression." They conclude that the New Deal "cartelization policies are a key factor behind the weak recovery." They say that the "abandonment of these policies coincided with the strong economic recovery of the 1940s."[58] Lowell E. Gallaway and Richard K. Vedder conclude that the "Great Depression was very significantly prolonged in both its duration and its magnitude by the impact of New Deal programs." They argue that without Social Security, work relief, unemployment insurance, and especially without the labor unions, business would have hired more workers and the unemployment rate would have been lower.[61] Few economists or economic historians have agreed with these speculations. The New Deal years 1933-36 (or indeed the FDR years 1933-45) showed the highest growth rates in the history of the American economy.

Unemployment continues[edit]

Darby counts WPA workers as employed; Lebergott as unemployed

source: Historical Statistics US (1976) series D-86; Smiley 1983[62]

The New Deal tried public works, farm subsidies and other devices to reduce unemployment, but FDR never completely gave up trying to balance the budget. Unemployment remained high throughout the New Deal years; business simply would not hire more people, especially the low skilled and supposedly "untrainable" men who had been unemployed for years and lost any job skill they once had. Keynesians later argued that by spending vastly more money—using fiscal policy—the government could provide the needed stimulus through the "multiplier" effect. Critics of Keynesianism said that would just take money out of the private sector, causing a negative multiplier effect there. However, no economist has written a full-scale Keynesian analysis of the depression, so it is difficult to evaluate how that model would work.

Unemployment peaked in 1933, at 24.9%, and by 1941 unemployment had subsided to 9.9%, which was near the 1930 level of 8.9%. [4] Unemployment increased 163% over the average of what it had been in 1930 by the third year of the New Deal. By contrast, recovery was well underway in Great Britain, with an increase of only 1.1%.

In recent years more influential among economists has been the monetarist interpretation of Milton Friedman, which did include a full-scale monetary history of what he calls the "Great Contraction." Friedman concentrated on the failures before 1933, and in his memoirs said the relief programs were an appropriate response. From 1935 to 1943, Friedman was himself a Keynesian who was (1941–43) an official spokesman for the New Deal before Congress; he did not at that time criticize any New Deal or Federal Reserve policies.

Apart from building up labor unions, the New Deal did not substantially alter the distribution of power within American capitalism.

Keynes visited to the White House in 1934 to urge President Roosevelt to do more deficit spending. Roosevelt complained to Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, "He left a whole rigmarole of figures--he must be a mathematician rather than a political economist." That is, Keynes had an abstract theory but no useful suggestions about what to do.

| Table 2: Unemployment (% labor force) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Lebergott | Darby |

| 1933 | 24.9 | 20.6 |

| 1934 | 21.7 | 16.0 |

| 1935 | 20.1 | 14.2 |

| 1936 | 16.9 | 9.9 |

| 1937 | 14.3 | 9.1 |

| 1938 | 19.0 | 12.5 |

| 1939 | 17.2 | 11.3 |

| 1940 | 14.6 | 9.5 |

| 1941 | 9.9 | 8.0 |

| 1942 | 4.7 | 4.7 |

| 1943 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| 1944 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| 1945 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

Fiscal Conservatism[edit]

Fiscal conservatism was a key component of the New Deal, as Zelizer (2000) demonstrates. It was supported by Wall Street and local investors and most of the business community; mainstream academic economists believed in it, as apparently did the majority of the public. Conservative southern Democrats, who favored balanced budgets and opposed new taxes, controlled Congress and its major committees. Even liberal Democrats at the time regarded balanced budgets as essential to economic stability in the long run, although they were more willing to accept short-term deficits. Public opinion polls consistently showed public opposition to deficits and debt. Throughout his terms, Roosevelt recruited fiscal conservatives to serve in his administration, most notably Lewis Douglas the Director of Budget from 1933 to 1934, and Henry Morgenthau, Jr., Secretary of the Treasury from 1934 to 1945. They defined policy in terms of budgetary cost and tax burdens rather than needs, rights, obligations, or political benefits. Personally, the president embraced their fiscal conservatism. Politically, he realized that fiscal conservatism enjoyed a strong wide base of support among voters, leading Democrats, and businessmen. On the other hand, there was enormous pressure to act–and spending money on high visibility programs attracted Roosevelt, especially if it tied millions of voters to him, as did the WPA.

Douglas proved too inflexible, and quit in 1934. Morgenthau made it his highest priority to stay close to Roosevelt, no matter what. Douglas' position, like many of the Old Right was grounded in a basic distrust of politicians and the deeply ingrained fear that government spending always involved a degree of patronage and corruption that offended his Progressive sense of efficiency. The Economy Act of 1933, passed early in the Hundred Days, was Douglas' great achievement. It reduced federal expenditures by $500 million, to be achieved by reducing veterans’ payments and federal salaries. Douglas cut government spending through executive orders that cut the military budget by $125 million, $75 million from the Post Office, $12 million from Commerce, $75 million from government salaries, and $100 million from staff layoffs. As Freidel concludes, "The economy program was not a minor aberration of the spring of 1933, or a hypocritical concession to delighted conservatives. Rather it was an integral part of Roosevelt's overall New Deal."[63] Revenues were so low that borrowing was necessary (only the richest 3% paid any income tax before 1942.) Douglas, therefore, hated the relief programs, which he said reduced business confidence, threatened the government's future credit, and had the "destructive psychological effects of making mendicants of self-respecting American citizens."[64] Roosevelt was pulled toward greater spending by Hopkins and Ickes, and as the 1936 election approached he decided to gain votes by attacking big business.

Morgenthau shifted with FDR, but at all times tried to inject fiscal responsibility; he deeply believed in balanced budgets, stable currency, reduction of the national debt, and the need for more private investment. The Wagner Act met Morgenthau's requirement because it strengthened the party's political base and involved no new spending. In contrast to Douglas, Morgenthau accepted Roosevelt's double budget as legitimate–that is a balanced regular budget, and an “emergency” budget for agencies, like the WPA, PWA and CCC, that would be temporary until full recovery was at hand. He fought against the veterans’ bonus until Congress finally overrode Roosevelt's veto and gave out $2.2 billion in 1936. His biggest success was the new Social Security program; he managed to reverse the proposals to fund it from general revenue and insisted it be funded by new taxes on employees. It was Morgenthau who insisted on excluding farm workers and domestic servants from Social Security because workers outside industry would not be paying their way.[65]

Deficits held relatively constant throughout the 1930s at about 40% of the GDP.[66]

Fascism and New Deal[edit]

- See also: Fascism and the New Deal