Jean-Francois Millet

From Nwe

From Nwe

| Jean-François Millet | |

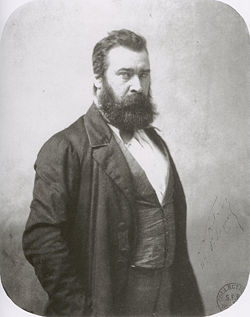

Portrait of Millet by Nadar. Date unknown, 1850-1870 |

|

| Birth name | Jean-François Millet |

| Born | October 4, 1814 Gruchy, Gréville-Hague, Normandy |

| Died | January 20, 1875 |

| Nationality | French |

| Field | Painting, Sculpting |

Jean-François Millet (October 4, 1814 - January 20, 1875) was a French painter whose style tightroped the line between naturalism and realism. He was also one of the founders of the Barbizon school in rural France. The Barbizon school (circa 1830–1870) of painters is named after the village of Barbizon near Fontainebleau Forest, France, where the artists gathered. The Barbizon painters were part of a movement towards realism in art in reaction to the more formalized romantic movement of the time.

During the Revolutions of 1848 artists gathered at Barbizon to follow the ideas of John Constable, making nature the subject of their paintings. Millet extended the idea from landscape to figures — peasant figures, scenes of peasant life, and work in the fields. In The Gleaners (1857), Millet portrays three peasant women working at the harvest. On the surface there appears to be no drama and no story told, merely three peasant women in a field.

Millet's Biography: Path to Fame

Jean François Millet was born in Gruchy near Gréville on Oct. 4, 1814. Much of his life endeavors concentrated on peasant subject matter because of the influence of his childhood. As a child, Millet grew up in a heavy-labor environment: farming to make a living. Knowing what it was like to live in poverty, Millet moved to Paris with aspirations of painting. To learn the traditions of classical and religious painting, he entered the studio of Paul Delaroche, a successful academic imitator of the revolutionary romanticist Eugène Delacroix. Millet stayed in Paris, supporting himself by making pastel reproductions of rococo masters, occasional oil portraits, and commercial signs. He studied with two painters from his home town of Cherborg, Bon Dumouchel and a copyist, Lucien-Theophile Langlois. Four years later, in 1841, Millet married Pauline Ono. The marriage only lasted for three years before Ono died. He remarried in 1845 to Catherine Lemaire. He exhibited much of his work in the Parisian Salons and one of his works was even accepted by the Salon of 1840. One of his premier works was the Winnower.

In the early stages of his career, Millet’s subject matter was more classical and religious. However, during the decade of the 1840s, after gaining the support of his contemporaries, he began to work on paintings for which he is now most known, his paintings of the peasantry. Together with Narcisse Diaz de la Peña and Théodore Rousseau, two landscape painters who were instrumental in forming the Barbizon school, Millet and the other Barbizon artists resisted the grand traditions of classical and religious painting, preferring a direct, unaffected confrontation with the phenomena of the natural world.[1] Millet moved to Barbizon where other artists lived in 1848. The picturesque village became his home for the rest of his life, until his death there on Jan. 20, 1875. During that period he produced his most mature and celebrated paintings, including The Gleaners (1857), the Angelus (1857-1859), the Sower (1850), and the Bleaching Tub (1861). The works are characterized by their simplicity; they generally depict one or two peasant figures quietly working in the fields. With sweeping, generalized brushwork and a monumental sense of scale, Millet gave his figures a unique sense of dignity and majesty.

During the late nineteenth century Millet's paintings became extremely popular, particularly among American audiences and collectors. As more radical styles appeared, however, his contribution became partially eclipsed; to eyes accustomed to Impressionism and Cubism, his work appeared sentimental and romantic.[2]

Influence of Other Artists

Jean-Francois Millet painted particularly original works; however, some of the artistic aspects of his painting can be attributed to the influence of Theodore Rousseau's The Porte aux Vaches in snow, and Baroque Painter Louis Le Nain. His Winnower is a clear example of his imitation of Le Nain, whose paintings consisted mostly of family life. The emphasis on color is evident and the monumentality of the figures in comparison to their landscape is also prevalent. Rousseau's use of landscape can be seen in many of Millet's preparatory drawings with its open, central vista and horizontally banded, linear composition formed by the trees in the background.[3]

Millet's Painting

Political controversy

While Millet's legacy as an adamant working-class supporter is engraved in stone, he did not lack his share of critics. In fact, it took a very long time for people to realize that Millet had no political intentions. Millet's work carried an aura of spirituality that few artists could match, but this spirituality was often mistaken for political propaganda. The works he received the most criticism for included his most famous work, Gleaners, Sower and the Hay Trussers. An anonymous critic accused Millet of depicting labor as a horrifying nightmare by emphasizing the ragged clothes of the peasants and putting the central focus on the misery of the peasant worker. A more known critic, Sabatier-Ungher said, The earth is fertile, it will provide, but next year, like this, you will be poor and you will work by the sweat of your brow, because we have so arranged it that work is a curse. [4] In other words, Millet is trying to awaken the oblivious peasants to the fact that this will be the way they live for their entire life. He, as critics often claimed, solidified the permanence of labor, and portrayed it as a never-ending plight of the peasant worker. During the 1850's and 1860's, Millet's work was considered a revolution of its own, compared to the French Revolution. One of the harshest of his critics, Paul de Saint-Victor, observed that one would have to look for a long time before one found a living example of his Man with a hoe, shown at the Salon of 1863. “Similar types," he wrote, "are not even seen in a mental hospital." [5] His most celebrated work, The Gleaners, shown at the salon of 1857, however was considered pretentious. The figures were "the three fates of pauperism; moreover, they had no faces and looked like scarecrows."[6]

The Gleaners

One of the most well known of Millet's paintings is The Gleaners (1857), depicting women stooping in the fields to glean the leftovers from the harvest. It is a powerful and timeless statement about the working class. The Gleaners is on display in Paris's Musée d'Orsay.

Picking up what was left of the harvest was regarded as one of the lowest jobs in society. However, by focusing strictly on the rugged curves of the figures and the brutal hunching of the backs, Millet portrayed these women as heroic figures. This is distinctly different than the standard, where servants were depicted in paintings as subservient to a noble or king. Here, light illuminates the women's shoulders as they carry out their work. Behind them, the field that stretches into the distance is bathed in golden light, under a wide, magnificent sky. The forms of the three figures themselves, nearly silhouetted against the lighter field, show balance and harmony.

Harvester's Resting

Millet preferred this painting to the rest of his work and he makes this fact clear to his audience with the fourteen figures—possibly representations of his own family—in the landscape. The fourteen figures is the most figures Millet has used in his paintings. Despite Millet's own claims, there is a strong social undertone as well as a biblical reference in this painting. "Harvester's Resting is also the most complex paintings he ever made. He worked on it for almost three years, and nearly fifty preparatory drawings survive. Although the subject of Harvesters Resting is a sad and serious one, the painting is very beautiful–the group of solid figures harmoniously interwoven, and the atmosphere around them golden with the sun-struck dust of the harvest." [7]

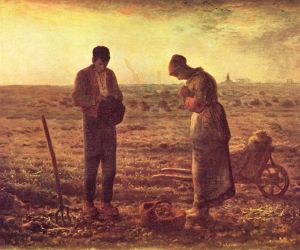

The Angelus

Commissioned by a wealthy American art collector, Thomas G. Appleton, and completed during the summer of 1857, Millet added a steeple and changed the initial title of the work, Prayer for the Potato Crop to The Angelus when the purchaser failed to take possession in 1859. Displayed to the public for the first time in 1865, the painting changed hands several times, increasing only modestly in value, since some considered the artist's political sympathies suspect. Upon Millet's death a decade later, a bidding war between the United States and France ensued, ending some years later with a price tag of 800,000 gold francs.

The disparity between the apparent value of the painting and the poor estate of Millet's surviving family was a major impetus in the invention of the droit de suite, intended to compensate artists or their heirs when works are resold.

One critic, Charles Tardieu said of the painting,

"masterpiece, and one of the masterpieces of contemporary art; a Realist painting certainly, but perhaps not as much as was first thought. The realism that lies in the provinciality of the subject, in the triviality of the figures, is then idealized, not only by the emotion with which the painter has translated his religious impression and the power of his two laborers' naive faith…. The prayer in it is so vigorously known that it appears, by the will of the artist, instilled there not only through the two peasants and their bowed poses, but even in the soil that they work, in this landscape of resigned austerity, even for the most skeptical of viewers." [8]

The Angelus was reproduced frequently in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Salvador Dalí was fascinated by this work, and wrote an analysis of it, The Tragic Myth of The Angelus of Millet. Rather than seeing it as a work of spiritual peace, Dalí believed it held messages of repressed sexual aggression. Dalí was also of the opinion that the two figures were praying over their buried child, rather than to the Angelus. Dalí was so insistent on this fact that eventually an X-ray was done of the canvas, confirming his suspicions: the painting contains a painted-over geometric shape strikingly similar to a coffin. [9] However, it is unclear whether Millet changed his mind on the meaning of the painting, or even if the shape actually is a coffin.

Frick Exhibit

During his lifetime, Millet's work was often praised and criticized simultaneously. Then, for a period, his work completely disappeared from exhibits and declined in popularity. In the early twenty-first century, eleven of his paintings were on display at the Frick Exhibition in Pittsburgh. The show itself carries 63 drawings and paintings of Millet that were obtained from other museums and private collections. [10] Millet's last painting is on display as well, titled Autumnn, The Haystacks, "captures a burst of sunlight raking across three large grain stacks, which tower over a meandering flock of sheep in the foreground. The image is mesmerizing in its fusion of the everyday with the eternal." [11]

Drawn into the Light Exhibition

Another famous Jean-Francois Millet exhibition was the Drawn into the Light at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in the art haven of New York. He himself was influenced by many artists, and has been the influence of artists that have followed him. "Millet's drawings are limpid and nuanced, with a remarkable feel for light and the weight of things." [12] Many of his landscape paintings and use of lighting are due to the influences of Poussin and Delacroix. They also have the ability to capture the attention of audiences in an awe-inspiring, almost unearthly way, a quality of Vermeer. "No one was more adept at pastels than he was, or more skilled at exploiting the bumpiness of textured paper to create a soft, shimmering effect, or at the technique of rubbing the lines made by conte crayons. Seurat, whose drawings are also sublime, idolized Millet because, among other things, Millet virtually invented the vaporous silhouettes that Seurat drew." [13]

Major Works

- Angelus, 1859

- L'Angelus

- The Gleaners, 1857

- Self Portrait, circa 1845-1846

- Abendlauten

- Wines and Cheeses

- Narcissi and Violets, circa 1867

- Churning Butter, 1866-1868

- Nude Study

- La Fileuse Chevriere Auvergnate

- Le Vanneur

- Landscape with a Peasant Woman, Early 1870s

- Portrait of a Naval Officer, 1845

- The Winnower

- The Wood Sawyers, 1848

Legacy

Jean-Francois Millet left a legacy that is neither socialist or biblical, but one that attends to one of the grimmer realities of life: poverty. In his own words, he says, "To tell the truth, the peasant subjects suit my temperament best; for I must confess, even if you think me a socialist, that the human side of art is what touches me most." His realist and naturalist influences eventually paved way for the Impressionism movement of the modern era.

Notes

- ↑ Carl Belz. "Millet, Jean François (1814-1875)." Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed. (Detroit: Gale Research, 1998)

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Frederick Hartt. Art: A History of Painting, Sculpture, and Architecture, Third ed. (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1989)

- ↑ Bradley Fratello, "France embraces Millet: the intertwined fates of The Gleaners and The Angelus." The Art Bulletin 85 (4) (Dec 2003): 685 (17)

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Gilian Shallcross, and Maureen Albano. "HARVESTERS RESTING.(painting by Jean-Francois Millet." Art School (Magazine): 35

- ↑ Fratello

- ↑ Gilles Néret. Salvador Dali 1904-1989. (Taschen America, 2000)

- ↑ WORKING-CLASS HERO MILLET, SUPERSTAR OF 19TH-CENTURY FRENCH ART, REGAINS PRESTIGE IN FRICK EXHIBIT. The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, OH), Feb. 19, 2000, 1E.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Michael Kimmelman. ART REVIEW; "Plucking Warmth From Millet's Light." The New York Times (August 27, 1999), NA.

- ↑ Ibid.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Belz, Carl. "Millet, Jean François (1814-1875)." Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed. Ed. Suzanne M. Bourgoin. Detroit: Gale Research, 1998. 17 vols.

- Eisenmann, Stephen F. Nineteenth Century Art, A Critical History, 2nd Edition London: Thames and Hudson, 2002. ISBN 0500283354

- Fratello, Bradley. "France embraces Millet: the intertwined fates of The Gleaners and The Angelus." The Art Bulletin 85 (4) (Dec 2003): 685 (17).

- Gardner, Helen. Art Through the Ages, Sixth Edition. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc. 1975. ISBN 0155037536

- Hartt, Frederick. Art: A History of Painting, Sculpture, Architecture. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1989. ISBN 0810918846

- Kimmelman, Michael. "ART REVIEW; Plucking Warmth From Millet's Light.(Leisure/Weekend Desk)." The New York Times. (August 27, 1999): 30 Aug. 2007

- The Plain Dealer. "WORKING-CLASS HERO MILLET, SUPERSTAR OF 19TH-CENTURY FRENCH ART, REGAINS PRESTIGE IN FRICK EXHIBIT.(ENTERTAINMENT)." The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, OH). Feb 19, 2000.

- Neret, Gilles. Salvador Dali 1904-1989. Taschen America, 2000. ISBN 3822859893

External links

All links retrieved April 9, 2018.

- BBC blog H2G2 anonymous Influence on Dali - grieving parents or praying peasants in The Angelus? entry posted July 6, 2001. www.bbc.co.uk.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Jean-Francois_Millet history

- Barbizon_school history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

- History of "Jean-Francois Millet"

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 09:21:34 | 90 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Jean-Francois_Millet | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF