Sikhism

From Nwe

From Nwe Sikhism is a religion that began in sixteenth-century Northern India with the life and teachings of Guru Nanak and nine successive human gurus. Etymologically, the word Sikhism derives from the Sanskrit root śiṣya meaning "disciple" or "learner." Adherents of Sikhism are known as “Sikhs” (students or disciples) and number over 23 million across the world. Most Sikhs live in the state of Punjab in India. Today, Sikhism is the fifth-largest organized religion in the world.

As a religion, philosophy and way of life, Sikhism is centered on the principle belief in one God (monotheism). For Sikhs, God is the same for all humankind regardless of one's religion. Sikhism encourages constant remembrance of God in one's life, honest living, equality among the sexes and classes, and sharing of the fruits of one's labors with others. The followers of Sikhism follow the teachings of the ten Sikh gurus, or enlightened leaders, as well as Sikhism's holy scripture—the Gurū Granth Sāhib—which includes the selected works of many authors from diverse socioeconomic and religious backgrounds. The text was decreed by Guru Gobind Singh, the tenth guru, as the final guru of the Sikh community. Sikhism is distinctly associated with the history, society and culture of the Punjab. In Punjabi, the teachings of Sikhism are traditionally known as the Gurmat (literally the teachings of the gurus) or the Sikh Dharma.

Philosophy

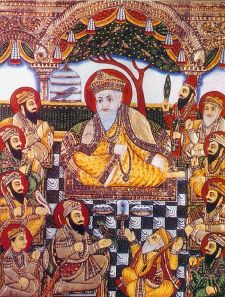

The traditions and philosophy of Sikhism were established by ten specific Gurus (spiritual teachers) from 1469 to 1708. Each guru added to and reinforced the message taught by the previous, resulting in the creation of the Sikh religion and philosophy.

Sikhism has roots in the religious traditions of northern India such as Sant Mat, Hindu Bhakti, and Sufism.[1] However, Nanak's teachings diverge significantly from Vaishnavism in their rejection of idol worship, the doctrine of divine incarnations, and a strict emphasis on inward devotion; Sikhism is professed to be a more difficult personal pursuit than Bhakti.[2] The evolution of Nanak's thoughts on the basis of his own experiences and study have also given Sikhism a distinctly unique character.

Scholars have presented Sikhism as both a distinct faith and a syncretic religion which combines some elements of Hinduism and Islam. Sikhs maintain that their religion was directly revealed by God, and many of them consider the notion that Sikhism is a syncretic religion to be offensive.

God

In Sikhism, God (termed Wahegurū) is formless, eternal, and unobserved: niraṅkār, akāl, and alakh. Nanak interpreted Vāhigurū as a single, personal and transcendental creator. The beginning of the first composition of Sikh scripture is the figure "1," signifying the unity of God. To achieve salvation, the devotee must develop an intimate faith in and relationship with God.[2] God is omnipresent and infinite, and is signified by the term ēk ōaṅkār. Sikhs believe that prior to creation, all that existed was God and his infinite hukam (will).[3] When God willed, the entire cosmos was created. From these beginnings, God nurtured "enticement and attachment" to māyā, or the human perception of reality.[4]

While a full understanding of God is beyond human beings,[2] Nanak described God as not wholly unknowable. God is omnipresent (sarav viāpak) in all creation and visible everywhere to the spiritually awakened. Nanak stressed that God must be seen from "the inward eye," or the "heart" of a human being: devotees must meditate to progress towards enlightenment. Nanak emphasized revelation through meditation, as its rigorous application permits the existence of communication between God and human beings.[2] God has no gender in Sikhism, though translations may incorrectly present a masculine God.

Central Teachings

The central teachings of Sikhism are summarized below as follows:

- Ek Onkar — Affirmation of monotheism (the belief that there is only one God)

- Nām simraṇ—remembrance of the divine Name—Sikhs are encouraged to verbally repeat the name of God in their hearts and on their lips

- Kirat karō—that a Sikh should balance work, worship, and charity, and should defend the rights of all creatures, and in particular, fellow human beings. This teaching encourages honest, hard work in society and rejects the practice of asceticism.

- Caṛdī kalā—Affirmation of an optimistic, view of life

- Vaṇḍ chakkō—Sikh teachings also stress the concept of sharing—through the distribution of free food at Sikh gurdwaras (laṅgar), giving charitable donations, and working for the betterment of the community and others (sēvā)

- Sikhism affirms the full equality of sexes, classes, and castes

Pursuing salvation

Nanak's teachings are founded not on a final destination of heaven or hell, but on a spiritual union with God which results in salvation. The chief obstacles to the attainment of salvation are social conflicts and an attachment to worldly pursuits, which commit men and women to an endless cycle of birth—a concept known as karma.

Māyā—defined as illusion or "unreality"—is one of the core deviations from the pursuit of God and salvation - people are distracted from devotion by worldly attractions which give only illusive satisfaction. However, Nanak emphasized māyā as not a reference to the unreality of the world, but of its values. In Sikhism, the influences of ego, anger, greed, attachment and lust—known as the Five Evils—are particularly pernicious. The fate of people vulnerable to the Five Evils is separation from God, and the situation may be remedied only after intensive and relentless devotion.[5]

Nanak described God's revelation—the path to salvation—with terms such as nām (the divine Name) and śabad (the divine Word) to emphasize the totality of the revelation. Nanak designated the word guru (meaning teacher) as the voice of God and the source and guide for knowledge and salvation.[6] Salvation can be reached only through rigorous and disciplined devotion to God. Nanak distinctly emphasized the irrelevance of outwardly observations such as rites, pilgrimages or asceticism. He stressed that devotion must take place through the heart, with the spirit and the soul.

History

Guru Nanak Dev (1469–1538), the founder of Sikhism, was born in the village of Rāi Bhōi dī Talvaṇḍī, now called Nankana Sahib, near Lahore (in what is present-day Pakistan).[7] His parents were Khatri Hindus of the Bedi clan. As a boy, Nanak was fascinated by religion, and his desire to explore the mysteries of life eventually led him to leave home. It was during this period that Nanak was said to have met Kabir (1440–1518), a saint revered by people of different faiths.

Sikh tradition states that at the age of thirty, Nanak went missing and was presumed to have drowned after going for one of his morning baths to a local stream called the Kali Bein. Three days later he reappeared and would give the same answer to any question posed to him: "There is no Hindu, there is no Muslim" (in Punjabi, "nā kō hindū nā kō musalmān"). It was from this moment that Nanak would begin to spread the teachings of what was then the beginning of Sikhism.[8] Although the exact account of his itinerary is disputed, he is widely acknowledged to have made four major journeys, spanning thousands of kilometers. The first tour being east towards Bengal and Assam, the second south towards Ceylon via Tamil Nadu, the third north towards Kashmir, Ladakh and Tibet, and the final tour west towards Baghdad and Mecca.[9]

Nanak was married to Sulakhni, the daughter of Moolchand Chona, a rice trader from the town of Batala. They had two sons. The elder son, Sri Chand was an ascetic and he came to have a considerable following of his own, known as the Udasis. The younger son, Lakshmi Das, on the other hand was totally immersed in worldly life. To Nanak, who believed in the ideal of rāj maiṁ jōg (detachment in civic life), both his sons were unfit to carry on the guruship.

Growth of the Sikh community

In 1538, Nanak chose his disciple Lahiṇā, a Khatri of the Trehan clan, as a successor to the guruship rather than either of his sons. Lahiṇā was named Guru Angad Dev and became the second guru of the Sikhs.[10] Nanak conferred his choice at the town of Kartarpur on the banks of the river Ravi, where Nanak had finally settled down after his travels. Though Sri Chand was not an ambitious man, the Udasis believed that the guruship should have gone to him, since he was a man of pious habits in addition to being Nanak's son. They refused to accept Angad's succession. On Nanak's advice, Angad shifted from Kartarpur to Khadur, where his wife Khivi and children were living, until he was able to bridge the divide between his followers and the Udasis. Angad continued the work started by Nanak and is widely credited for standardizing the Gurmukhī script as used in the sacred scripture of the Sikhs.

Guru Amar Das became the third Sikh guru in 1552 at the age of 73. During his guruship, Goindval became an important centre for Sikhism. Guru Amar Das preached the principle of equality for women by prohibiting purdah (the requirement that women cover their bodies) and sati (widows sacrificing themselves at the funeral of their husband). Amar Das also encouraged the practice of laṅgar and made all those who visited him attend laṅgar before they could speak to him.[11] In 1567, Emperor Akbar sat with the ordinary and poor people of Punjab to have laṅgar. Amar Das also trained 146 apostles of which 52 were women, to manage the rapid expansion of the religion.[12] Before he died in 1574 at the age of 95, he appointed his son-in-law Jēṭhā, a Khatri of the Sodhi clan, as the fourth Sikh guru.

Jēṭhā became Guru Ram Das and vigorously undertook his duties as the new guru. He was responsible for the establishment of the city of Ramdaspur later to be named Amritsar.

Amar Das began building a cohesive community of followers with initiatives such as sanctioning distinctive ceremonies for birth, marriage and death. Amar Das also established the manji (comparable to a diocese) system of clerical supervision. [6]

Amar Das's successor and son-in-law Ram Das founded the city of Amritsar, which is home of the Harimandir Sahib and regarded widely as the holiest city for all Sikhs. When Ram Das's youngest son Arjun Dev succeeded him, the line of male gurus from the Sodhi Khatri family was established: all succeeding gurus were direct descendants of this line. Arjun Dev was responsible for compiling the Sikh scriptures. Arjun Dev was captured by Mughal authorities who were suspicious and hostile to the religious order he was developing.[13] His persecution and death inspired his successors to promote a military and political organization of Sikh communities to defend themselves against the attacks of Mughal forces.

The Sikh gurus established a mechanism which allowed the Sikh religion to react as a community to changing circumstances. The sixth guru, Guru Har Gobind, was responsible for the creation of the Akal Takht (throne of the timeless one) which serves as the supreme decision-making centre of Sikhdom and sits opposite the Harimandir Sahib. The Sarbat Ḵẖālsā (a representative portion of the Khalsa Panth) historically gathers at the Akal Takht on special festivals such as Vaisakhi or Diwali and when there is a need to discuss matters that affect the entire Sikh nation. A gurmatā (literally, guru's intention) is an order passed by the Sarbat Ḵẖālsā in the presence of the Gurū Granth Sāhib. A gurmatā may only be passed on a subject that affects the fundamental principles of Sikh religion; it is binding upon all Sikhs. The term hukamnāmā (literally, edict or royal order) is often used interchangeably with the term gurmatā. However, a hukamnāmā formally refers to a hymn from the Gurū Granth Sāhib which is given as an order to Sikhs.

In 1581, Guru Arjun Dev—youngest son of the fourth guru—became the fifth guru of the Sikhs. In addition to being responsible for building the Harimandir Sahib (often called the Golden Temple), he prepared the Sikh sacred text known as the Ādi Granth (literally the first book) and included the writings of the first five gurus. Thus the first Sikh scripture was compiled and edited by the fifth guru, Arjun Dev, in 1604. In 1606, for refusing to make changes to the Granth and for supporting an unsuccessful contender to the throne, he was tortured and killed by the Mughal ruler, Jahangir.[14]

Political advancement

Guru Har Gobind became the sixth guru of the Sikhs. He carried two swords—one for spiritual and the other for temporal reasons (known as mīrī and pīrī in Sikhism).[15] Sikhs grew as an organized community and developed a trained fighting force to defend themselves. In 1644, Guru Har Rai became guru followed by Guru Har Krishan, the boy guru, in 1661. No hymns composed by these three gurus are included in the Sikh holy book.[16]

Guru Teg Bahadur became guru in 1665 and led the Sikhs until 1675. Teg Bahadur was executed by Aurangzeb for helping to protect Hindus, after a delegation of Kashmiri Pandits came to him for help when the emperor condemned them to death for failing to convert to Islam.[17] He was succeeded by his son, Gobind Rai who was just nine years old at the time of his father's death. Gobind Rai further militarized his followers, and was baptized by the Pañj Piārē when he formed the Khalsa in 1699. From here on in he was known as Guru Gobind Singh.[18]

From the time of Nanak, when it was a loose collection of followers who focused entirely on the attainment of salvation and God, the Sikh community had significantly transformed. Even though the core Sikh religious philosophy was never affected, the followers now began to develop a political identity. Conflict with Mughal authorities escalated during the lifetime of Teg Bahadur and Gobind Singh. The latter founded the Khalsa in 1699. The Khalsa is a disciplined community that combines its religious purpose and goals with political and military duties.[1] After Aurangzeb killed four of his sons, Gobind Singh sent Aurangzeb the Zafarnāmā (Notification/Epistle of Victory).

Shortly before his death, Gobind Singh ordered that the Gurū Granth Sāhib (the Sikh Holy Scripture), would be the ultimate spiritual authority for the Sikhs and temporal authority would be vested in the Khalsa Panth (The Sikh Nation/Community).[19]

The Sikh community's embrace of military and political organization made it a considerable regional force in medieval India and it continued to evolve after the demise of the gurus. Banda Bahadur, a former ascetic, was charged by Gobind Singh with the duty of punishing those who had persecuted the Sikhs. After the guru's death, Banda Bahadur became the leader of the Sikh army and was responsible for several attacks on the Mughal Empire. He was executed by the emperor Jahandar Shah after refusing the offer of a pardon if he converted to Islam.[20]

After the death of Banda Bahadur, a loose confederation of Sikh warrior bands known as misls formed. With the decline of the Mughal Empire, a Sikh empire arose in the Punjab under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, with its capital in Lahore and limits reaching the Khyber Pass and the borders of China. The order, traditions and discipline developed over centuries culminated at the time of Ranjit Singh to give rise to the common religious and social identity that the term "Sikhism" describes.[21]

After the death of Ranjit Singh, the Sikh kingdom fell into disorder and eventually collapsed with the Anglo-Sikh Wars, which brought the Punjab under British rule. Sikhs supported and participated in the Indian National Congress, but also formed the Shiromani Gurdwara Prabandhak Committee and the Shiromani Akali Dal to preserve Sikhs religious and political organization. With the partition of India in 1947, thousands of Sikhs were killed in violence and millions were forced to leave their ancestral homes in West Punjab.[22] Even though Sikhs enjoyed considerable prosperity in the 1970s, making Punjab the most prosperous state in the nation, a fringe group led by cleric Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale began demanding an independent state named Khalistan, led to clashes between militant groups and government forces, as well as communal violence.[23]

Guru Gobind Singh was the final guru in human form. Before his death, Guru Gobind Singh decreed that the Gurū Granth Sāhib would be the final and perpetual guru of the Sikhs.[19]

Scripture

There are two primary sources of scripture for the Sikhs: the Gurū Granth Sāhib and the Dasam Granth. The Gurū Granth Sāhib may be referred to as the Ādi Granth—literally, The First Volume—and the two terms are often used synonymously. Here, however, the Ādi Granth refers to the version of the scripture created by Arjun Dev in 1604. The Gurū Granth Sāhib refers to the final version of the scripture created by Gobind Singh.

Adi Granth

It is believed that the Ādi Granth was compiled primarily by Bhai Gurdas under the supervision of Guru Arjun Dev between the years 1603 and 1604.[24] It is written in the Gurmukhī script, which is a descendant of the Laṇḍā script used in the Punjab at that time.[25] The Gurmukhī script was standardized by Arjun Dev for use in the Sikh scriptures and is thought to have been influenced by the Śāradā and Devanāgarī scripts. An authoritative scripture was created to protect the integrity of hymns and teachings of the Sikh gurus and selected bhagats. At the time, Arjun Dev tried to prevent undue influence from the followers of Prithi Chand, the guru's older brother and rival.[26]

The original version of the Ādi Granth is known as the kartārpur bīṛ and is currently held by the Sodhi family of Kartarpur.

Guru Granth Sahib

The final version of the Gurū Granth Sāhib was compiled by Guru Gobind Singh. It consists of the original Ādi Granth with the addition of Guru Teg Bahadur's hymns. It was decreed by Gobind Singh that the Granth was to be considered the eternal, living guru of all Sikhs:

- Punjabi: ਸੱਬ ਸਿੱਖਣ ਕੋ ਹੁਕਮ ਹੈ ਗੁਰੂ ਮਾਨਯੋ ਗ੍ਰੰਥ ।

- Transliteration: Sabb sikkhaṇ kō hukam hai gurū mānyō granth.

- English: All Sikhs are commanded to take the Granth as Guru.

It contains compositions by the first five gurus, Guru Teg Bahadur and just one śalōk (couplet) from Guru Gobind Singh.[27] It also contains the traditions and teachings of sants (saints) such as Kabir, Namdev, Ravidas and Sheikh Farid along with several others.[21]

The bulk of the scripture is classified into rāgs, with each rāg subdivided according to length and author. There are 31 main rāgs within the Gurū Granth Sāhib. In addition to the rāgs, there are clear references to the folk music of Punjab. The main language used in the scripture is known as Sant Bhāṣā, a language related to both Punjabi and Hindi and used extensively across medieval northern India by proponents of popular devotional religion.[1] The text further comprises over five thousand śabads, or hymns, which are poetically constructed and set to classical form of music rendition, can be set to predetermined musical tāl, or rhythmic beats.

The Granth begins with the Mūl Mantra, an iconic verse created by Nanak:

- Punjabi: ੴ ਸਤਿ ਨਾਮੁ ਕਰਤਾ ਪੁਰਖੁ ਨਿਰਭਉ ਨਿਰਵੈਰੁ ਅਕਾਲ ਮੂਰਤਿ ਅਜੂਨੀ ਸੈਭੰ ਗੁਰ ਪ੍ਰਸਾਦਿ ॥

- ISO 15919 transliteration: Ika ōaṅkāra sati nāmu karatā purakhu nirabha'u niravairu akāla mūrati ajūnī saibhaṅ gura prasādi.

- Simplified transliteration: Ik ōaṅkār sat nām kartā purkh nirbha'u nirvair akāl mūrat ajūnī saibhaṅ gur prasād.

- English: There is One God, He is the supreme truth, He, the Creator, is without fear and without hate. He, the omnipresent, pervades the universe. He is not born, nor does he die again to be reborn. By His grace shalt thou worship Him.

All text within the Granth is known as gurbānī. Gurbānī, according to Nanak, was revealed by God directly, and the authors wrote it down for the followers. The status accorded to the scripture is defined by the evolving interpretation of the concept of gurū. In the Sant tradition of Nanak, the guru was literally the word of God. The Sikh community soon transferred the role to a line of men who gave authoritative and practical expression to religious teachings and traditions, in addition to taking socio-political leadership of Sikh adherents. Gobind Singh declared an end of the line of human gurus, and now the Gurū Granth Sāhib serves as the eternal guru for the Sikhs, with its interpretation vested with the Sikh community.[1]

Dasam Granth

The Dasam Granth (formally dasvēṁ pātśāh kī granth or The Book of the Tenth Master) is an eighteenth-century collection of miscellaneous works generally attributed to Guru Gobind Singh. The teachings of Gobind Singh were not included in Gurū Granth Sāhib, the holy book of the Sikhs, and instead were collected in the Dasam Granth. Unlike the Gurū Granth Sāhib, the Dasam Granth was never declared to hold guruship. The authenticity of some portions of the Granth has been questioned and the appropriateness of the Granth's content still causes much debate.

The entire Granth is written in the Gurmukhī script, although most of the language is actually Braj and not Punjabi. Sikh tradition states that Mani Singh collected the writings of Gobind Singh after his death to create the Granth.[28]

Janamsakhis

The Janamsākhīs (literally birth stories), are writings which profess to be biographies of Guru Nanak Dev. Although not scripture in the strictest sense, they provide an interesting look at Nanak's life and the early start of Sikhism. There are several—often contradictory and sometimes unreliable—Janamsākhīs and they are not held in the same regard as other sources of scriptural knowledge.

Observances and ceremonies

Observant Sikhs adhere to long-standing practices and traditions to strengthen and express their faith. The daily recitation from memory of specific passages from the Gurū Granth Sāhib, especially the Japu (or Japjī, literally chant) hymns is recommended immediately after rising and bathing. Family customs include both reading passages from the scripture and attending the gurdwara (also gurduārā, meaning the doorway to God). There are many gurdwaras prominently constructed and maintained across India, as well as in almost every nation where Sikhs reside. Gurdwaras are open to all, regardless of religion, background, caste or race.

Worship in a gurdwara consists chiefly of singing of passages from the scripture. Sikhs will commonly enter the temple, touch the ground before the holy scripture with their foreheads, and make an offering. The recitation of the eighteenth century ardās is also customary for attending Sikhs. The ardās recalls past sufferings and glories of the community, invoking divine grace for all humanity.[29]

The most sacred shrine is the Harimandir Sahib in Amritsar, famously known as the “Golden Temple.” Groups of Sikhs regularly visit and congregate at the Harimandir Sahib. On specific occasions, groups of Sikhs are permitted to undertake a pilgrimage to Sikh shrines in the province of Punjab in Pakistan, especially at Nankana Sahib and the samādhī (place of cremation) of Maharaja Ranjit Singh in Lahore.

Festivals in Sikhism mostly center on the lives of the gurus and Sikh martyrs. The SGPC, the Sikh organization in charge of upkeep of the gurdwaras, organizes celebrations based on the new Nanakshahi calendar. This calendar is highly controversial among Sikhs and is not universally accepted. Several festivals (Hola Mohalla, Diwali and Guru Nanak's birthday) continue to be celebrated using the Hindu calendar. Sikh festivals include the following:

- Gurpurabs are celebrations or commemorations based on the lives of the Sikh gurus. They tend to be either birthdays or celebrations of Sikh martyrdom.

- Vaisakhi normally occurs on April 13 and marks the beginning of the new spring year and the end of the harvest. Sikhs celebrate it because on Vaisakhi in 1699, the tenth guru, Gobind Singh, established the Khalsa baptismal tradition.

- Diwali (also known as bandī chōḍ divas) celebrates Guru Hargobind's release from the Gwalior Jail on October 26, 1619.

- Hola Mohalla occurs the day after Holi and is when the Khalsa Panth gather at Anandpur and display their fighting skills.

Ceremonies and customs

Nanak taught that rituals, religious ceremonies or empty worship is of little use and Sikhs are discouraged from fasting or going on pilgrimages.[30] However, during the period of the later gurus, and due to increased institutionalization of the religion, some ceremonies and rites did arise. Sikhism is not a proselytizing religion and most Sikhs do not make active attempts to gain converts. However, converts to Sikhism are welcomed, although there is no formal conversion ceremony.

Upon a child's birth, the Gurū Granth Sāhib is opened at a random point and the child is named using the first letter on the top left-hand corner of the left page. All boys are given the middle name or surname Singh, and all girls are given the middle name or surname Kaur.[31] Sikhs are joined in wedlock through the anand kāraj ceremony. Sikhs marry when they are sufficient age (child marriage is taboo), and without regard for the future spouse's caste or descent. The marriage ceremony is performed in the company of the Gurū Granth Sāhib; around which the couple circles four times. After the ceremony is complete, the husband and wife are considered "a single soul in two bodies."[32]

According to Sikh religious rites, neither husband nor wife are permitted to divorce. A Sikh couple that wishes to divorce may be able to do so in a civil court—but this is not condoned. Upon death, the body of a Sikh is usually cremated. If this is not possible, any means of disposing the body may be employed. The kīrtan sōhilā and ardās prayers are performed during the funeral ceremony (known as antim sanskār).[33]

Baptism and the Khalsa

Khalsa (meaning "pure") is the name given by Gobind Singh to all Sikhs who have been baptized or initiated by taking ammrit in a ceremony called ammrit sañcār. The first time that this ceremony took place was on Vaisakhi in 1699 at Anandpur Sahib in India. It was on that occasion that Gobind Singh baptized the Pañj Piārē who in turn baptized Gobind Singh himself.

Baptized Sikhs are bound to wear the “Five Ks” (in Punjabi known as pañj kakkē or pañj kakār), or articles of faith, at all times. The tenth guru, Gobind Singh, ordered these Five Ks to be worn so that a Sikh could actively use them to make a difference to their own and to others' spirituality. The five items are: Kēs (uncut hair), Kaṅghā (small comb), Kaṛā (circular heavy metal bracelet), Kirpān (ceremonial short sword), and kacchā (special undergarment). The Five Ks have both practical and symbolic purposes.[34]

Sikhism Today

Worldwide, Sikhs number more than 23 million, but more than 90 percent of Sikhs still live in the Indian state of Punjab, where they form close to 65 percent of the population. Large communities of Sikhs live in the neighboring states and indeed large communities of Sikhs can be found across India. However, Sikhs comprise only about two percent of India's entire population. Migration beginning from the nineteenth century led to the creation of significant diasporic communities of Sikhs outside India in Canada, the United Kingdom, the Middle East, East Africa, Southeast Asia and more recently, the United States, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand.

Smaller populations of Sikhs are found in Mauritius, Sri Lanka, Nepal, Fiji and other countries.

As with most world religions, there are groups of Sikhs (such as the Namdharis, Ravidasis and Udasis) who do not adhere to the mainstream principles followed by most Sikhs. Some of these groups may not consider themselves a part of Sikhism, although similarities in beliefs and principles firmly render them a part of the Sikh religious domain. Groups such as the Nirankaris have a history of bad relations with mainstream Sikhism, and are considered pariahs by some Sikhs. Others, such as the Nihangs, tend to have little difference in belief and practice, and are considered Sikhs proper by mainstream Sikhism.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Geoffrey Parrinder, World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present (London: Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited, 1971, ISBN 0871961296), 259.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Parrinder, 252.

- ↑ Gurū Granth Sāhib, 1035: “For endless eons, there was only utter darkness. There was no earth or sky; there was only the infinite Command of His Hukam.” Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ Gurū Granth Sāhib, 1036: “When He so willed, He created the world. Without any supporting power, He sustained the universe. He created Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva; He fostered enticement and attachment to Maya.” Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ Parrinder, 253.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Parrinder, 254.

- ↑ Khushwant Singh, The Illustrated History of the Sikhs (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006, ISBN 0195677471), 12-13. Also, as according to the Purātan Janamsākhī (the birth stories of Nanak).

- ↑ Christopher Shackle and Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair, Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures (London: Routledge, 2005, ISBN 0415266041), xiii-xiv.

- ↑ Singh, 14.

- ↑ Shackle and Mandair, xv.

- ↑ Kartar Singh Duggal, Philosophy and Faith of Sikhism (Himalayan Institute Press, 1988, ISBN 0893891096), 15.

- ↑ Sandeep Singh Brar, The Sikhism Homepage: Guru Amar Das. Retrieved Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ Parrinder, 255.

- ↑ Shackle, xv-xvi.

- ↑ Cynthia Mahmood, A Sea of Orange (Philadelphia, PA: Xlibris, 2002, ISBN 140102856X), 16.

- ↑ Shackle, xvi.

- ↑ Swami Rama, Celestial Song/Gobind Geet: The Dramatic Dialogue Between Guru Gobind Singh and Banda Singh Bahadur (Himalayan Institute Press, 1986, ISBN 0893891037), 7-8.

- ↑ Singh, 37-38.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Gurinder Singh Mann, The Making of Sikh Scripture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0195130243), 21.

- ↑ Singh, 47-53.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Parrinder, 256.

- ↑ Gyanendra Pandey, Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001, ISBN 0521002508), 33.

- ↑ Donald L. Horowitz, The Deadly Ethnic Riot (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003, ISBN 0520236424), 482-485.

- ↑ Ernest Trumpp, The Ādi Granth or the Holy Scriptures of the Sikhs (Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2004, ISBN 8121502446) (original 1877), 1xxxi.

- ↑ George Abraham Grierson, The Linguistic Survey of India (Motilal Banarsidass, 1967, ISBN 8185395276) (original 1927), 624.

- ↑ Gurinder Singh Mann, The Making of Sikh Scripture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 0195130243), 19.

- ↑ Sandeep Singh Brar, The Sikhism Homepage: Sri Guru Granth Sahib - Authors & Contributors Retrieved September 26, 2020..

- ↑ W. H. McLeod, Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993, ISBN 0791414256), 60-61.

- ↑ Parrinder, 260.

- ↑ Gurū Granth Sāhib, 75: “Pilgrimages, fasts, purification and self-discipline are of no use, nor are rituals, religious ceremonies or empty worship.” Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ Clinton Herbert Loehlin, The Sikhs and Their Scriptures, 2nd ed. (Lucknow Publishing House, 1964) (original 1958), 42.

- ↑ Anand Sanskar : (Sikh Matrimonial Ceremony and Conventions) Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ Funeral Ceremonies (Antam Sanskar) Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ David Simmonds, Believers All: A Book of Six World Religions (Nelson Thornes, 1992, ISBN 0174370571), 120-121.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Duggal, Kartar Singh. Philosophy and Faith of Sikhism. Himalayan Institute Press, 1988. ISBN 0893891096

- Grierson, George Abraham. The Linguistic Survey of India. Motilal Banarsidass, 1967 (original 1927). ISBN 8185395276

- Horowitz, Donald L. The Deadly Ethnic Riot. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2003. ISBN 0520236424

- Loehlin, Clinton Herbert. The Sikhs and Their Scriptures, 2nd ed. Lucknow Publishing House, 1964 (original 1958).

- Mahmood, Cynthia. A Sea of Orange. Philadelphia, PA: Xlibris, 2002. ISBN 140102856X

- Mann, Gurinder Singh. The Making of Sikh Scripture. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0195130243

- McLeod, W. H. Studying the Sikhs: Issues for North America. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1993. ISBN 0791414256

- Pandey, Gyanendra. Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. ISBN 0521002508

- Parrinder, Geoffrey. World Religions: From Ancient History to the Present. London: Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited, 1971. ISBN 0871961296

- Rama, Swami. Celestial Song/Gobind Geet: The Dramatic Dialogue Between Guru Gobind Singh and Banda Singh Bahadur. Himalayan Institute Press, 1986. ISBN 0893891037

- Shackle, Christopher and Arvind-Pal Singh Mandair. Teachings of the Sikh Gurus: Selections from the Sikh Scriptures. London: Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0415266041

- Simmonds, David. Believers All: A Book of Six World Religions. Nelson Thornes, 1992. ISBN 0174370571

- Singh, Khushwant. The Illustrated History of the Sikhs. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0195677471

- Trumpp, Ernest. The Ādi Granth or the Holy Scriptures of the Sikhs. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers, 2004 (original 1877). ISBN 8121502446

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2023.

- The Sikhism Home Page - General resource site introducing the main concepts of Sikhism

- All About Sikhs - Sikhism resource site

- Sri Granth - Guru Granth Sahib search engine with additional scriptural resources

- SikhiWiki - Collaborative Sikh encyclopedia

- SikhNet - Popular Sikh community website

- Reflections On Gurbani – Well-researched articles on various themes mentioned in the SGGS

| Gurus: | Guru Nanak Dev | Guru Angad Dev | Guru Amar Das | Guru Ram Das | Guru Arjan Dev | Guru Har Gobind | Guru Har Rai | Guru Har Krishan | Guru Teg Bahadur | Guru Gobind Singh | Sikh Bhagats |

| Philosophy: | Beliefs and principles | Underlying values | Prohibitions | Technique and methods | Other observations |

| Practices: | Ardās | Amrit | Chaṛdī Kalā | Dasvand | Five Ks | Kirat Karō | Kirtan | Langar | Nām Japō | Simran | Three Pillars | Vaṇḍ Chakkō |

| Scripture: | Guru Granth Sahib | Dasam Granth | Sarab Loh Granth | Bani | Chaupai | Jaap Sahib | Japji Sahib | Mool Mantar | Rehras | Sukhmani | Tav-Prasad Savaiye |

| More: | Ek Onkar | Gurdwara | History | Khalsa | Khanda | Literature | Music | Names | Places | Politics | Satguru | Sikhs | Waheguru |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:46:57 | 147 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Sikhism | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF