London

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) London:

By: Joseph Jacobs

- Massacre of 1189.

- Old Jewry.

- In the Barons' War.

- Synagogues Closed.

- The Return.

- Organization.

- Social Condition in 1750.

- Ashkenazic Institutions.

- Second Sephardic Defection.

- Struggle for Emancipation.

- Reform Movement.

- The Jewish Press.

- Further Consolidation (1856-1871).

- The Rabbinate.

- Social Condition About 1880.

- The Russian Exodus.

- Commission on Alien Immigration.

- Intellectual Progress.

- Population.

- —Present Conditions (Statistics):

- Synagogues.

- Charity.

- Defectives and Delinquents.

- Education.

- Social Institutions.

- Occupations.

- Friendly and Benefit Societies.

- Zionism.

- —Typography:

Capital city of England. According to William of Malmesbury, William the Conqueror brought certain Jews from Rouen to London about 1070; and there is no evidence of their earlier existence in England. Besides these settlers from Rouen, London was visited by Jews from the Rhine valley, one of whom, from Mayence, had a friendly dispute, about 1107, with Gilbert Crispin, Abbot of Westminster. Another Jew was even converted to Christianity by Anselm ("Opera," III., epist. cxvii.). The earliest reference to a collective Jewish settlement is in the "Terrier of St. Paul's," of about 1115, where mention is made of some land in the "Jew street," which from its description corresponds to a part of Old Jewry. In 1130 the Jews of London incurred a fine of £2,000—an enormous sum in those days—"for the sick man whom they killed "; possibly some charge of magic was involved. Among the persons paying this fine was "Rubi Gotsce" (Rabbi Josce or Joseph), whose sons Isaac and Abraham were the chief members of the London community toward the end of the century, and whose house in Rouen was in possession of the family as late as 1203 ("Rot. Cart." 105b). In 1158 Abraham ibn Ezra visited London and wrote there his letter on the Sabbath and his "Yesod Mora." Up to 1177 London was so far the principal seat of Jews in England that Jews dying in any part of the country had to be buried in the capital, probably in the cemetery known afterwardas "Jewin Garden," and now as "Jewin street." The expulsion of the Jews from the Isle of France in 1182 brought about a large acquisition to the London community, which was probably then visited by Judah Sir Leon, whose name occurs as "Leo le Blund" in a list of London Jews who contributed to the Saladin tithe Dec., 1185. This list includes Jews from Paris, Joigny, Pontoise, Estampes, Spain, and Morocco.

Massacre of 1189.The massacre of the Jews at the coronation of Richard I. Sept. 3, 1189 ( see England ), was the first proof that the Jews of England had of any popular ill-will against them. Richard did practically nothing to punish the rioters, though he granted a special form of charter to Isaac fil Joce, the chief London Jew of the time, "and his men," which is the earliest extant charter of English Jews. In 1194 the Jews of London contributed £486 9s. 7d. out of £1,803 7s. 7d. toward the ransom of the king: in the list of contributors three Jewish "bishops" are mentioned—Deulesalt, Vives, and Abraham. In the same year was passed the "Ordinance of the Jewry," which in a measure made London the center of the English Jewry for treasury purposes, Westminster becoming the seat of the Exchequer of the Jews , which was fully organized by the beginning of the thirteenth century. Meanwhile anti-Jewish feeling in London had spread to such an extent that King John found it necessary in 1204 to rebuke the mayor for its existence.

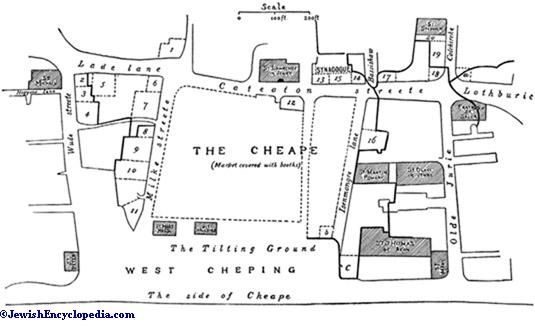

Old Jewry.After the massacre of 1189, it would appear, the Jews began to desert Old Jewry, and to spread westward into the streets surrounding the Cheape, or market-place, almost immediately in front of the Guildhall. To a certain extent the Jews were crowded out from Old Jewry by the Church, which during the twelfth century established there the monastery of St. Thomas of Acon, St. Mary Colechurch, and at the back St. Martin Pomary, looking upon Ironmonger lane, where, it would seem, the Jews' College, or high school of all the English Jews, was located.

Escheats and purchases tended also to drive the Jews away from this quarter, the corner houses of Ironmonger lane being taken from Jews by the Earl of Lancaster and the Earl of Essex respectively. The Jewish dwellings spread along Gresham street, Milk street, and Wood street. The fact that the chief noblemen of the time were anxious to obtain them shows these houses to have been strongly built, as was indeed the complaint at the time of the riots.

Besides their predominant position, due to the existence of the Exchequer of the Jews, and which brought to London all the Jewish business of the country, the Jews of the capital had also spiritual domination, inasmuch as their presbyter or chief rabbi held a position analogous to that of the archbishop ( see Presbyter ).

The chief synagogue of the London Jewry at this date appears to have been on the site of Bakewell Hall . It probably continued to be used down to the Expulsion, though for certain reasons it was in private hands from 1283 to 1290. Another synagogue, in the northeast corner of Old Jewry, was handed over to the Fratres de Sacca, while still another was given to St. Anthony's Hospital, on the site of which is now the City Bank. Reference to more than one synagogue among the Jews of London is distinctly seen in the proclamations which were ordered to be made in the "synagogues" to determine whether or not a person was in debt to the Jews (see "Select Pleas of the Jewish Exchequer," ed. Rigg, p. 9).

In the Barons' War.The Jews of London suffered from their position as buffer between the king and the barons. In 1215 the barons opposing John sacked the Jewish quarter and used the tombstones of the Jewish cemetery to repair Ludgate (Stow, "Survey of London," ed. Thoms, p. 15). Similarly, in the trouble with Simon de Montfort, in 1263, the barons looted the London Jewry in pursuance of their opposition to the oppression of the king, into whose hands fell the debts of the Jews in London and elsewhere. This outburst had been preceded in 1262 by a popular riot against the Jews in which no less than 700 had been killed. A curious suit which followed the death of a Jew on this occasion is given in "Select Pleas," pp. 73-76, from which it appears that some of the Jews of that time took refuge in the Tower of London. It is a mistake, however, to suppose that there was a separate Jewry in that neighborhood. Most of the trials that took place with regard to ritual or other accusations were held in the Tower ( see Norwich ). Nevertheless the Tower continued to be the main protection of the Jews against the violence of the mob; and they are reported to have been among its chief defenders in 1269 against the Earl of Gloucester and the disinherited.

In 1244 London witnessed an accusation of ritual murder, a dead child having being found with gashes upon it which a baptized Jew declared to be in the shape of Hebrew letters. The body was buried with much pomp in St. Paul's Cathedral, and the Jews were fined the enormous sum of 60,000 marks (about £40,000). Later on, in 1279, certain Jews of Northampton, on the accusation of having murdered a boy in that city, were brought to London, dragged at horses' tails, and hanged.

Toward the later part of their stay in London the Jews became more and more oppressed and degraded, and many of them, to avoid starvation, resorted to doubtful expedients, such as clipping. This led at times to false accusations; and on one occasion a Jew named Manser fil Aaron sued for an inquiry concerning some tools for clipping which had been found on the roof of his house near the synagogue (1277). In the following year no fewer than 680 Jews were imprisoned in the Tower, of whom 267 were hanged for clipping the coinage. On another occasion the lord mayor gave orders that no meat declared unfit by the Jewish butchers should be exposed for sale to Christians (Riley, "Chron." p. 177).

Synagogues Closed.Disputes as to jurisdiction over the Jews often occurred between the Jewish Exchequer and the lord mayor. Thus in the year 1250 pleas of disseizin of tenements of the city of London were withdrawn from the cognizance of the justice of theJews and assigned for trial in the mayor's court, though they were reassigned to the Exchequer in 1271. In that year Jews were prevented from acquiring any more property in London, on the ground that this might diminish the Church tithes ("De Antiquis Legibus Liber," pp. 234 et seq. ). The Church was very careful to prevent any encroachment on its rights; and it endeavored to curtail those of the Synagogue as much as possible. In 1283 Bishop Peckham caused all synagogues in the diocese of London to be closed; and it is for this reason that there exists no record of any synagogue falling into the hands of the king at the Expulsion (1290), though it is probable that the house held by Antera, widow of Vives fil Mosse of Ironmonger lane, was identical with the synagogue and was used for that purpose.

At the Expulsion the houses held by the Jews fell into the hands of the king, and were with few exceptions transferred to some of his favorites. In all, the position of about twenty-five houses can still be traced (see accompanying map), though it is doubtful whether the 2,000 Jews of London could have been accommodated in that small number of dwellings. As will be seen, the houses were clustered around the Cheape or market. Many of their owners were members of the Hagin family, from which it has been conjectured Huggin lane received its name (but see Hagin Deulacres ). Traces of the presence of Jews are found also in surrounding manors which now form part of London, as West Ham, Southwark, etc.

The Return.

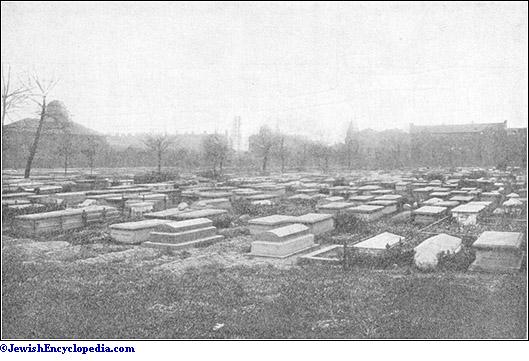

From the Expulsion to the seventeenth century London was only occasionally visited by Jews, mainly from Spain. In 1542 a certain number of persons were arrested on the suspicion of being Jews. Indeed, their presence appears to have become so common that in an old play ("Every Woman in Her Humour," 1609) a citizen's wife thus advises any one desirous of going to court: "You may hire a good suit at a Jew's." From this it would appear that Jewish traffic in old clothes had already begun. Toward the middle of the reign of Charles I. a number of Spanish Jews, headed by Antonio Fernandez Carvajal , settled in London in order to share in the benefits of the trade between Holland and the Spanish colonies. They passed as Spaniards, and attended mass at the chapel of the Spanish embassy; but when the Independents, with Cromwell at their head, became predominant in English affairs, several of these Jews assisted him in obtaining information about Spanish designs ( see Intelligencers ). Meanwhile Manasseh ben Israel attempted to secure formal permission for the return of the Jews to England. At the conference at Whitehall on Dec. 18, 1655, the matter was left undecided; but it was put to a practical test in the following year by the Robles case, as a result of which Cromwell granted the lease of a burial-ground at Mile End for 999 years ("Jew. Chron." Nov. 26, 1880). Even previous to this the Jews had met for worship in a private house fitted up as a synagogue in Creechurch lane, Leadenhall street; and it is possible to assume the existence of a second meeting-place at St. Helens in the same neighborhood by 1662. These places of worship were fairly well known to the general public, though they were protected by treble doors and other means of concealment. Thomas Greenhalgh visited the one in Creechurch lane in 1664; and from the number of births in that year it would appear that about 280 Jewish souls resided in London at the beginning ofthe reign of Charles II. These must have increased considerably by 1677, when more than fifty Jewish names occur in the first London directory (Jacobs and Wolf, "Bibl. Anglo-Jud." pp. 59-61), implying a population of at least 500 Jewish souls. There is evidence of a number of aliens pretending to be Jews in that very year (L. Wolf, in "Jew. Chron." Sept. 28, 1894, p. 10).

Much opposition was directed against the Jews by the citizens of London, who regarded them as formidable rivals in foreign trade. Besides a petition of Thomas Violett against them in 1660, attempts were made in 1664, 1673, and 1685 to put a stop to their activity and even to their stay in England. On the last occasion the ingenious point was made that the grants of denization given to the London Jews by Charles II. had expired with his death, and that their goods were, therefore, liable to alien duty (Tovey, "Anglo-Judaica," pp. 287-295); and this contention was ultimately sustained. The more important merchants of London, however, recognized the advantages to be derived from the large Jewish trade with the Spanish and Portuguese colonies and with the Levant, to which, indeed, England was largely indebted for its imports of bullion. Rodriques Marques at the time of his death (1668) had no less than 1,000,000 milreis consigned to London from Portugal. Accordingly individual Jews were admitted as brokers on the Royal Exchange, though in reality not eligible by law. Solomon Dormido, Manasseh ben Israel's nephew, was thus admitted as early as 1657, and others followed, till the south-eastern corner of the Exchange was definitely set aside for the Jewish brokers. In 1697 a new set of regulations was passed by a committee of the Exchange appointed by the aldermen, which limited the number of English brokers to 100, of alien brokers to 12, and of Jewish brokers to 12. Of the 12 Jews admitted all appear to have been Sephardim except Benjamin Levy, who was probably an Ashkenazi. A petition in 1715 against the admission of Jews to the Exchange was refused by the board of aldermen.

Organization.

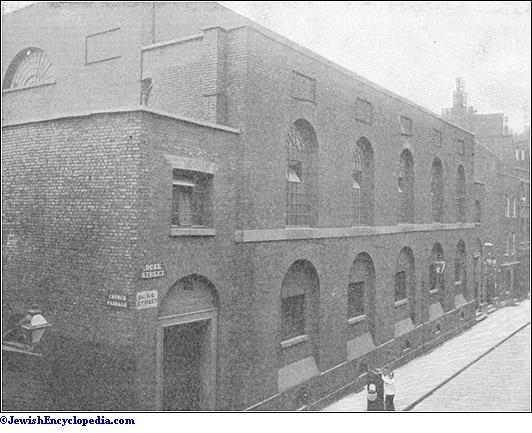

The Sephardim soon established communal institutions, following, it may be conjectured, the example of Amsterdam, from which city most of them had emigrated. The Gates of Hope School was founded as early as 1664; and this was followed by the Villa Real Schools in 1730. The Sephardic Orphan Asylum had been established as early as 1703, and a composite society, whose title commenced with "Honen Dalim," was founded in 1704 to aid lying-in women, support the poor, and to give marriage portions to fatherless girls. In 1736 a Marriage Portion Society was founded, and eleven years later the Beth Holim, or hospital, came into existence, this in turn being followed in 1749 by the institution known as "Mahesim Tobim." Thanks to these and other minor institutions, the life of a Sephardic Jew in London was assisted at every stage from birth, through circumcision, to marriage, and onward to death, while even the girls of the community were assisted with dowries. This unfortunately had a pauperizing effect, which came to be felt toward the beginning of the nineteenth century. All these institutions centered round the great Sephardic synagogue built in Bevis Marks Sept., 1701 ( see Bevis Marks Synagogue ). This was a center of light and learning, having the society Etz Haim (founded as early as 1664) for the study of the Law. Later this was merged with the yeshibah into one institution called the "Medrash," which is still in existence. In the early days of the community almost all the names of importance were connected with Bevis Marks, e.g. , the Cortissos, Lagunas, Mendes, Pimentels, Samudas, Salvadors, Sarmentos, Suassos, and Villa Reals; the Nietos and the Azevedos likewise represented a high state of culture and Hebrew learning.

Social Condition in 1750.

By the middle of the eighteenth century these and other families, such as the Franks, Treves, Seixas, Nunes, Lamegos, Salomons, Pereiras, and Francos, had accumulated considerable wealth, mainly in foreign commerce; and in a pamphlet of the time it was reckoned that there were 100 families with an income ranging between £1,000 and £2,000, while the average expenditure of the 1,000 families raised above pauperism was estimated at £300 per annum. The whole community was reckoned to be worth £5,000,000 ("Further Considerations of the Act," pp. 34-35, London, 1753). The Jews were mainly concerned in the East-Indian and West-Indian trades and in the importation of bullion. The Jamaica trade was almost monopolized by them ( ib. pp. 44-49). The most important member of the community was Samson Gideon , who by his coolness during the crisis of the South Sea Bubble and the rising of 1745 rendered great service to the government and acquired large means for himself. The riots that followed the passage of the bill of 1753 for the naturalization of Jews had in many ways a disastrous effect upon the Sephardic section of the community. Despairing of emancipation, a large number of the wealthiest and most cultured either were baptized themselves or had their children baptized, Gideon leading the way in the latter expedient. His son became Lord Eardley in the Irish peerage. One consequence of the rejection of the naturalization bill of 1753 was the formation of the Board of Deputies, then known as the "Deputados of the Portuguese Nation," really an extension of the Committee of Diligence formed to watch the passage of the naturalization bill through the Irish Parliament in 1745. The Board of Deputies came into existence as a sort of representative body whose first business was to congratulate George III. on his accession. As indicated by its earlier name, its membership was confined to Sephardim, though byarrangement representatives of the "Dutch Jews" were allowed to join in their deliberations ( see London Board of Deputies ).

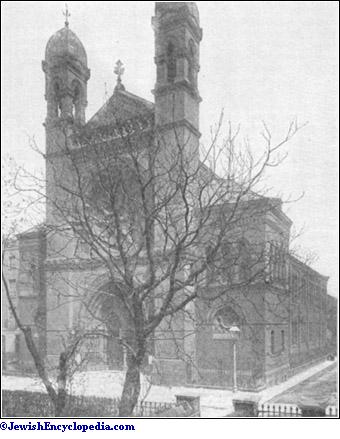

Meanwhile the "Dutch Jews" or Ashkenazim had from the beginning of the century been slowly increasing in numbers and importance. They had established a synagogue as early as 1692 in Broad street, Mitre square; and thirty years later the congregation was enabled by the generosity of Moses Hart (Moses of Breslau) to remove to a much more spacious building in Duke's place, Aldgate, still known as the "Great Shool." His brother, Aaron Hart, was established as the chief rabbi; and his daughter, Mrs. Judith Levy, contributed liberally to the synagogue's maintenance. Three years later a schism occurred, and the Hambro' Synagogue was founded. It was not till 1745 that the Jews of the German ritual found it necessary to establish any charity. The Hakenosath Berith was then organized, to be followed as late as 1780 by the Meshivath Nephesh. Rigid separation existed between the two sections of the community. Even in death they were divided: the Ashkenazic cemetery was at Alderney road, Mile End.

The social condition of the Ashkenazim toward the end of the eighteenth century was by no means satisfactory. Apart from a very few distinguished merchants like Abraham and Benjamin Goldsmid, Levy Barent Cohen, and Levy Salomons, the bulk of the Ashkenazic community consisted of petty traders and hawkers, not to speak of the followers of more disreputable occupations. P. Colquhoun, in his "Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis" (London, 1800), attributes a good deal of crime and vice to their influence; and his account is confirmed by less formal sketches in books like P. Egan's "Life in London" and by the caricatures of Rowlandson and his school. The lower orders of the Sephardic section also were suffering somewhat from demoralization. Prize-fighters like Aby Belasco, Samuel Elias, and Daniel Mendoza, though they contributed to remove some of the prejudice of the lower orders, did not help to raise the general tone.

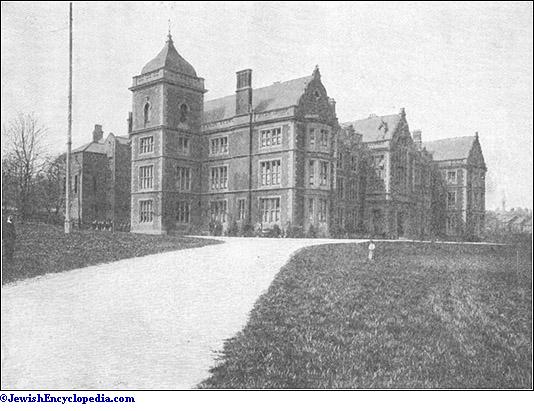

The revelations of Colquhoun led earnest spirits within the community to seek for remedies; and Joshua van Oven with Colquhoun's assistance drafted a plan for assisting the Jewish poor which was destined to bear fruit fifty years later in the Board of Guardians. Attention was directed to the education of the poor in 1811, when the Westminster Jews' Free School was established; and six years later the Jews' Free School was founded in Ebenezer square, and replaced a Talmud Torah founded in 1770. The first head master was H. N. Solomon, who afterward founded a private school at Edmonton which, together with thatof L. Neumegen at Highgate, afterward at Kew, educated most of the leaders of the Ashkenazim during the first two-thirds of the nineteenth century. Even earlier, care had been taken of orphans. By the exertions of Abraham and Benjamin Goldsmid the sum of £20,000 was collected between 1795 and 1797, with which in 1806 the Jews' hospital, called "Neveh Zedek," was opened June 28, 1807, at Mile End for the support of the aged poor and for the education of orphan children. This was removed to Norwood in 1863 to a building erected on ground presented by Barnett Meyers. A similar institution, the Jews' Orphan Asylum, founded in 1831, was amalgamated with the Neveh Zedek in 1876; and these were supplemented by the National and Infant schools founded in 1836, and by the Jews' Infant School founded in 1841 by Walter Josephs. Provision for the aged poor was made by the Aged Needy Society, founded in 1829, and by the almshouse established by Abraham Moses and Henry Salomon nine years later. The blind were cared for from 1819 onward by the Institution for the Relief of the Indigent Blind. The poor were cared for by a committee of the three London synagogues—the Great, the Hambro', and the New.

Second Sephardic Defection.Meanwhile echoes of the Mendelssohnian movement had reached London, besides which the general wealth of the Sephardic community had brought its members in contact with the main currents of culture. One of the Sephardim, Emanuel Mendes da Costa, had been secretary of the Royal Society; and his brother Solomon had presented to the newly founded British Museum 200 Hebrew books, which formed the nucleus of the magnificent Hebrew collection of that library. Moses Mendez had proved himself a poetaster of some ability; and Oliver Goldsmith in his "Haunch of Venison" depicted a Jewish journalist of his time as a characteristic figure. But the "mahamad" of Bevis Marks went on in its old way without regard to any changes, spiritual or otherwise, in the community which it ruled; inflicting fines, and repelling many of the most promising members who were getting in touch with more refined methods of worship. Many of them ceased their connection with the Synagogue, either formally by becoming baptized or by resigning and allowing their children to be brought up in the dominant faith. Among the families thus deserting the Synagogue at the beginning of the nineteenth century may be enumerated the Basevis, D'Israelis, Ricardos, Samudas, Uzziellis, Lopezes, and Ximines. Not that the Sephardim were left without some important figures: Hananel de Castro, David Abravanel Lindo, Jacob and Moses Mocatta, not to mention Sir Moses Montefiore, were still left to uphold the more rigid traditions of Bevis Marks (Gaster, "Hist. of Bevis Marks," p. 172, London, 1901).

The hegemony in the community was thus transferred to the Ashkenazic section, which had been reenforced by the powerful personality of Nathan Meyer Rothschild, who had removed from Manchester to London in 1805 and who thenceforth became the central figure of the community. By his side stood the venerable figure of the "Rav," Solomon Herschel. Even in the literary sphere the Ashkenazim began to show ability. Whereas David Levi had been almost their sole representative at the end of the eighteenth century, in the first third of the nineteenth Michael Josephs, Moses Samuels, and Hyman Hurwitz treated the various branches of Hebrew learning; and the arts were represented by John Braham in secular, and by the two Aschers in sacred, music. Against these names the Sephardim could only show those of Elias Hyam Lindo andGrace Aguilar in letters and that of Carlo Delpini in drama.

Struggle for Emancipation.Though the parliamentary struggle for emancipation was intended for the benefit of all British Jews, and has, therefore, been described in some detail under England , it centered mainly around London. The influence of the Jews in the city had increased. David Salomons was one of the founders of the London and Westminster Bank; the London Docks began their great career through the influence of the Goldsmids; the Alliance Insurance Company was in large measure the creation of Sir Moses Montefiore and his brother-in-law, Nathan Rothschild. These and similar institutions brought Jewish merchants into ever-widening relations with men of influence in the city. Their bid for justice was widely supported by the citizens of London. Thus, at the first attempt to pass the "Jew Bill" in 1830 the second reading was supported by a petition of no fewer than 14,000 citizens of London; and this was supplemented at the second attempt in 1833 by a petition of 1,000 influential names from Westminster. Again, the Sheriffs' Declaration Bill of 1835 was in reality concerned with the shrievalty of London, for which the popular David Salomons was making a gallant fight; in this he succeeded that year, to be followed two years later by Moses Montefiore, who was soon afterward knighted by Queen Victoria. In the same year (1835) Salomons was elected alderman, but was unable to occupy that office owing to his religion. For ten years he urged the right of his coreligionists to such a position, till at last he succeeded in getting a bill passed allowing Jews to become aldermen in the city of London and, thereby, eligible as lord mayor. Salomons was the first Jewish sheriff (1835), the first Jewish alderman (1847), and the first Jewish lord mayor (1855) of London. He was clearly destined to be the first Jew elected member of Parliament, though, appropriately enough, it was Baron Lionel Rothschild who first actually took his seat as member for the city of London, which had shown so much sympathy for Jewish emancipation ( see England ).

The sympathy thus attracted to Jews in the city was prominently shown during the Damascus Affair , when a Mansion House meeting was held (July 3, 1840) to protest against the threatened disaster. Incidentally, the struggle for Reform aided in opening out new careers for the disfranchised Jews of London. Francis Goldsmid, one of the most strenuous fighters for the cause, was admitted to the bar in 1833, though there were doubts as to his eligibility. He was followed in 1842 by John (afterward Sir John) Simon, who was ultimately one of the last sergeants-at-law.

Reform Movement.Meanwhile the community in both its sections was rent by a schism which left traces almost to the end of the century. Alike among the Ashkenazim and the Sephardim the more cultured members had been increasingly offended by the want of decorum shown both at Bevis Marks and the "Great Shool." Protests were made in 1812 and 1828 in the former synagogue, and in 1821 and 1824 in the latter; but on Dec. 4, 1836, matters were brought to a crisis by a definite proposal for Reform presented to the mahamad by a number of the "Yehidim." The petition was rejected as were similar ones in 1839 and in 1840, so that in 1840 twenty-four gentlemen, eighteen of the Sephardic and six of the Ashkenazic section of the community, determined to organize a congregation in which their ideas as to decorum in the service should be carried out. The new congregation dedicated its synagogue in Burton street Jan. 27, 1842, notwithstanding a "caution" which had been issued Oct. 24, 1841, against the prayer-book to be used by it, and a "ḥerem" issued five days before the inauguration of the synagogue against all holding communion with its members. This ban was not removed till March 9, 1849. For the further history of the movement see Reform Judaism . The schism produced disastrous effects upon the harmony of the community. The older congregations would not even allow deceased members of the new one to be buried in their graveyard; and it was necessary to establish a new cemetery at Ball's Pond (1843). The Board of Deputies, under the influence of Sir Moses Montefiore, refused to recognize the new congregation as one qualified to solemnize valid Jewish marriages; and a special clause of the Act of 1856 had to be passed to enable the West London Synagogue of British Jews to perform such marriages.

The Jewish Press.It is not without significance that the beginnings of the Jewish press in London coincided in point of time with the stress of the Reform controversy. Both "The Voice of Jacob," edited by Jacob Franklin, and "The Jewish Chronicle," edited by D. Meldola and Moses Angel—the latter of whom had in the preceding year become head master of the Jews' Free School, over which he was to preside for nearly half a century—came into existence in 1841. About the same time a band of German Jewish scholars established themselves in England and helped to arouse a greater interest in Jewish literature on scientific principles than had been hitherto displayed. Among these should be especially mentioned Joseph Zedner, keeper of the Hebrew books in the British Museum; the eccentric but versatile Leopold Dukes; H. Filipowski; L. Loewe; B. H. Ascher; T. Theodores; Albert Löwy; and Abraham Benisch, who was to guide the fortunes of "The Jewish Chronicle" during the most critical years of its career. The treasures of Oxford were about this time visited by the great masters Zunz and Steinschneider. They found few in England capable of appreciating their knowledge and methods, Abraham de Sola, David Meldola, and Morris Raphall being almost the only English Jews with even a tincture of rabbinic learning. On the other hand, the native intellect was branching out in other directions. Showing distinction in the law were James Graham Lewis, Francis Goldsmid, and John Simon; in dramatic management, Benjamin Lumley; in song, Mombach in the synagogue, and Henry Russell outside it; in music, Charles Sloman, Charles K. Salaman, and Sir Julius Benedict; in painting, Solomon Alexander Hart, the first Jewish R.A., and Abraham Solomon; in commerce, besides the Rothschilds and Goldsmids, the Wormses, Sassoons, Sterns, andSir Benjamin Phillips were rising names distinguished both within and without the community. J. M. Levy and Lionel Lawson were securing a large circulation for the first penny London newspaper, the "Daily Telegraph." Confining their activities within the community were men like Barnet Abrahams, dayyan of the Sephardim; Sampson Samuel; H. N. Solomon; N. I. Valentine; the Beddingtons; Louis Merton; and Sampson Lucas. All these may be said to have flourished in the middle of the century, toward the end of the struggle for complete independence.

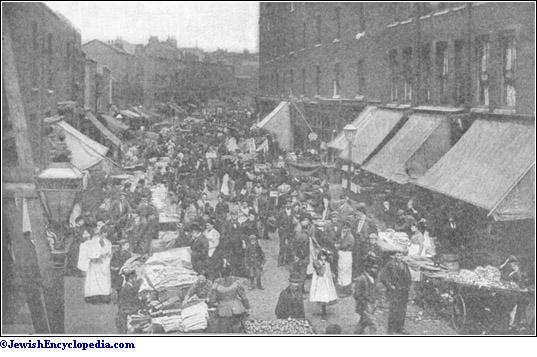

Further Consolidation (1856-1871).With them, but of a later generation, were growing up men who were destined between 1850 and 1880 further to consolidate the London community, now firmly established in the respect and confidence of the other citizens. The chief rabbi, N. M. Adler, began the process by establishing Jews' College for the training of Jewish ministers, in 1860 following it up, in cooperation with Dayyan Barnet Abrahams, with the establishment of the Jewish Association for the Diffusion of Religious Knowledge. Ephraim Alex with the aid of the energetic Lionel L. Cohen founded in 1859 the Board of Guardians for the Relief of the Jewish Poor to revise the system of charity conducted jointly by the three synagogues according to the treaty of 1805. This body soon developed loan, industrial, apprenticeship, visitation, and immigration committees, and for eighteen years (1862-79) took medical care of the Jewish poor, mainly under the supervision of Dr. A. Asher. Lionel Cohen, together with the last-mentioned, then devoted his attention to the solution of the financial and other problems brought about by the western extension of the London ghetto up to the middle of the century. The Jews of London had remained concentered in the Whitechapel district with the classic "Petticoat lane" as a nucleus; but as wealth increased among the Ashkenazic Jews a steady western exodus took place, so that it was necessary as early as 1855 to establish, under the ministry of the Rev. A. L. Green, in Great Portland street, a branch synagogue of the "Great Shool." Synagogues at Bayswater (1863), in the Borough (1867), and at North London (1868) were further evidences of the dispersion tendency; and it became necessary to secure harmony in divine service and consolidation in financial responsibility by bringing these synagogues under one management.

At the suggestion of Chief Rabbi N. M. Adler, the three city synagogues—the Great, the Hambro', and the New—with their western branches at Portland street and Bayswater agreed to a scheme (April 19, 1868), which was submitted to the Charity Commissioners of England and embodied by them in an Act of Parliament. This was passed July 14, 1870, although the legislature hesitated to establish the Synagogue just at the time when it was disestablishing the Irish Church. The original five synagogues have since been joined by ten others ( see United Synagogue ). One of the consequences of this arrangement, which upon the face of it appears to be merely financial, was to give a certain pontifical importance to the chief rabbi, without whose consent, according to a special declaration attached to but not forming part of the Act of Parliament, no changes in ritual could be undertaken by any constituent synagogue.

The Rabbinate.Indeed, one of the characteristic features of the London community has always been the importance of the chief rabbi (called among the Sephardim "haham") of the prominent congregation, around whom as a sort of center of crystallization the community has rallied. At first the Sephardim held this position, which had been secured by the important work of David Nieto, who became chief of the Sephardim in 1702 and was one of the most distinguished Jews of his time, being equally noted as philosopher, physician, mathematician, and astronomer. His predecessors, Jacob Sasportas (1656-66) and Solomon Ayllon (1689-1701), were not suited either by character or by attainments to acquire great influence. David Nieto was succeeded by his son Isaac, who in turn was followed by Moses Gomez de Mesquita (d. 1751). Moses Cohen d'Azevedo again raised the position of haham to some consequence during his rule (1765-84). Of his successors, Raphael Meldola (1805-28), Benjamin Artom (1866-1879), and Moses Gaster, the present incumbent (elected in 1887), have been the most distinguished.

But by the end of the eighteenth century the "Ravs" or chief rabbis of the Ashkenazim had begun to vie in importance with the hahamim of the Sephardim. The first of these was Aaron Hart (Uri Phoebus), brother of Moses Hart, founder of the Great Synagogue. He was succeeded by Hirschel Levin (sometimes called "Hirschel Löbel" and "Hart Lyon") who held office only seven years (1756-63), and then returned to the Continent. He was succeeded by David Tebele Schiff, who was chief rabbi from 1765 to 1792, and who founded a hereditary rabbinate for the next century, though his successor, Solomon Herschell (1802-42), was related to Schiff's predecessor, Hirschel Levin. Chief Rabbi N. M. Adler, who followed Herschell, was a relative of Schiff, and did much for the harmonizing of the London community; Jews' College, the United Synagogue, and, to a certain extent, the Board of Guardians owe their existence to his initiative. He was succeeded by his son, Herman Adler, the present (1904) incumbent of the post.

Besides Jews' College, the Board of Guardians, and the United Synagogue, the same generation arranged for a more efficient performance of its duties toward Jews oppressed in other lands. This function would naturally have fallen to the Board of Deputies; but, owing to its action with regard to the Reform Synagogue, certain members of this latter, especiallySir Francis Goldsmid and Jacob Waley, determined to form an independent institution to act for the British dominions in the same way that the Alliance Israélite Universelle had acted for the Continent. Owing to the Franco-Prussian war the Alliance had lost all support in Germany, and increased support from England had become necessary; this was afforded by the Anglo-Jewish Association , founded in 1871 with Albert Löwy as its secretary, who was instrumental also in founding the Society of Hebrew Literature in 1873.

Social Condition About 1880.By the beginning of the last quarter of the nineteenth century the London Jewish community had fully overcome the difficulties which had beset it at the beginning of the century; and it now organized all branches of its activity in a systematic and adequate manner. A series of remarkably able public servants—Asher Asher at the United Synagogue, A. Benisch at the "Jewish Chronicle," Moses Angel at the Jews' Free School, A. Löwy at the Anglo-Jewish Association, S. Landeshut at the Board of Guardians, and S. Almosnino, secretary of the Bevis Marks Synagogue and of almost all the Sephardic institutions—gave a tone of dignity as well as of efficiency to communal affairs. They were supported by leaders, some of whom, as Sir Julian Goldsmid and Baron Henry de Worms (afterward Lord Pirbright), had shown their capacity in national affairs, while others, like Lionel L. Cohen and his brother Alfred, Barrow Emanuel, David Benjamin, and Charles Samuel (to mention only those who are dead), had devoted their great abilities and administrative capacity to the internal needs of the community. Other members of the community were attaining distinction in the various branches of professional life. Sir George Jessel was the most distinguished judge, Judah P. Benjamin the most renowned barrister, and George Lewis the most noted solicitor practising English law. In medicine Ernest Hart, Henry Behrend, and R. Liebreich were noted; and in chemistry Ludwig Mond had become distinguished. Taste and capacity for literature were being shown by Sydney M. Samuel and Amy Levy; Frederic II. Cowen and in a less degree Edward Solomon were gaining distinction in music; and David James was famous in acting.

It was estimated about the year 1883 that the total Jewish population of London then numbered 47,000 persons. Of these, 3,500 were Sephardim (including 500 "Reformers"); 15,000 could trace their descent from the Ashkenazim of the eighteenth century; 7,500 from Jews who had settled in England in the early part of the century; 8,000 were of German or Dutch origin; and the remaining 13,000 were Russian and Polish. What might be called the native element thus outnumbered the foreign contingent by 26,000 to 21,000 (Jacobs, "Jewish Statistics," iii.). The various social classes into which they were divided were summarized by the same observer as follows, the numbers of the first four classes being determined from estimates of Jewish names in the "London Directory," of the last three from the actual statistics of Jewish charitable institutions; the number of shopkeepers and petty traders also were based on the last-mentioned source ( ib. ii.):

| Position. | Individuals. | Family Income. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professional and retired living W. | 1,200 | 100 | at | £10,000 |

| Rich merchants living W | 5,400 | 1,400 | " | 1,000 |

| Merchants with private houses living N., S., and E. | 3,600 | 800 | " | 500 |

| Professional and retired living N., S., and E. | 800 | 200 | " | 250 |

| Shopkeepers | 12,500 | 3,000 | " | 200 |

| Petty traders | 11,000 | 2,000 | " | 100 |

| Servants, etc. | 500 | ....... | 30 | |

| Board of Guardians, casuals and chronic | 7,911 | 1,000 | " | 50 |

| 1,884 | " | 10 | ||

| Other paupers and afflicted | 2,242 | ........ | 10 | |

| Russian refugees | 1,947 | |||

The total income was about £3,900,000, or an average per head of £82.

As regards their occupations, an examination of the London directory for those merchants sufficiently important to appear in its pages resulted in the following classification ( ib. v.):

| Class. | No. of Trades or Professions. | Individuals. |

|---|---|---|

| Merchants and factors | 84 | 689 |

| Clothing | 68 | 799 |

| Furniture | 49 | 348 |

| Food | 33 | 348 |

| Stationery | 19 | 111 |

| Jewelry | 17 | 245 |

| Leather | 17 | 81 |

| Iron | 13 | 70 |

| Instruments | 11 | 33 |

| Tobacco | 9 | 164 |

| Money-dealers | 5 | 33 |

| Toys | 4 | 51 |

| Professions | 15 | 154 |

There were but three occupations having over one hundred names: Stock Exchange brokers, 138; general merchants, 131; and tailors, 123. Then came clothiers, 89; bootmakers, 80; city of London brokers, 78; diamond-cutters, 78; furniture-brokers, 60; watchmakers, 57. The trades in which Jewish merchants had the largest representation were those in coconuts, oranges, canes and umbrellas, meerschaum pipes, and valentines.

The Russian Exodus.Unfortunately this prosperous condition of the community was rudely disturbed by the Russian persecutions of 1881; these mark an epoch in Anglo-Saxon Jewry, upon whose members has fallen the greatest burden resulting from them. On Jan. 11 and 13, 1882, appeared in "The Times" of London an account of the persecution of the Jews in Russia, written by Joseph Jacobs, which drew the attention of the whole world to the subject and led to a Mansion House meeting (Feb. 1) and to the formation of a fund which ultimately amounted to more than £108,000 for the relief of Russo-Jewish refugees. This was supplemented by a further sum of £100,000 in 1890, when a similar indignation meeting was held at the Guildhall to protest against the May Laws ( see Mansion House and Guildhall Meetings ).

The circumstances of the case, however, prevented the Russo-Jewish Committee, even under the able chairmanship of Sir Julian Goldsmid, from doing much more than supplement the work of the Board of Guardians, upon which fell the chief burden of the Russian exodus into England. But thepublicity of the protest made on these occasions, and the large sums collected, naturally made the London community the head of all concerted attempts to stem the rising tide of Russian oppression, and gave London for a time the leading position among the Jewish communities of the world. As passing events which helped to confirm the consciousness of this proud position may be mentioned the centenary in 1885 of Sir Moses Montefiore's birth, celebrated throughout the world, and the Anglo-Jewish Historical Exhibition (suggested and carried out by Isidore Spielmann) at the Albert Hall, London, in 1887. This exhibition led, six years later, to the foundation of the Jewish Historical Society of England.

The number of refugees permanently added to the London Jewish community—most of them merely passing through on their way to America—was not of very large proportions; but an average of about 2,500 in a condition of practical destitution annually added to a community of less than 50,000 souls naturally taxed the communal resources to the utmost. To prevent evils likely to result from the landing of refugees unacquainted with the English language and customs, the Poor Jews' Temporary Shelter and the Jewish Association for the Protection of Girls and Women were founded in 1885.

The newcomers generally showed a tendency to reject or neglect the religious supremacy of the English chief rabbi; and to check this and to serve other purposes a Federation of East End Synagogues was effected in 1887 under the auspices of Samuel (afterward Sir Samuel) Montagu. The want of capacity and technical skill among the newcomers, or "greeners," caused them to fall into the hands of hard taskmasters, and resulted in their becoming victims of the "sweating system," which formed the subject of a parliamentary inquiry (1888-90), due to the not overfriendly efforts of Arnold White. The poverty resulting from this system led to serious evils in the way of overcrowding with resulting immorality. Several remedial institutions were founded to obviate these evil results in the case of boys, the most prominent of which were the Jewish Lads' Brigade (1885) and the Brady Street Club for Working Boys. It was nevertheless found necessary in 1901 to establish an industrial school for Jewish boys who had shown criminal tendencies.

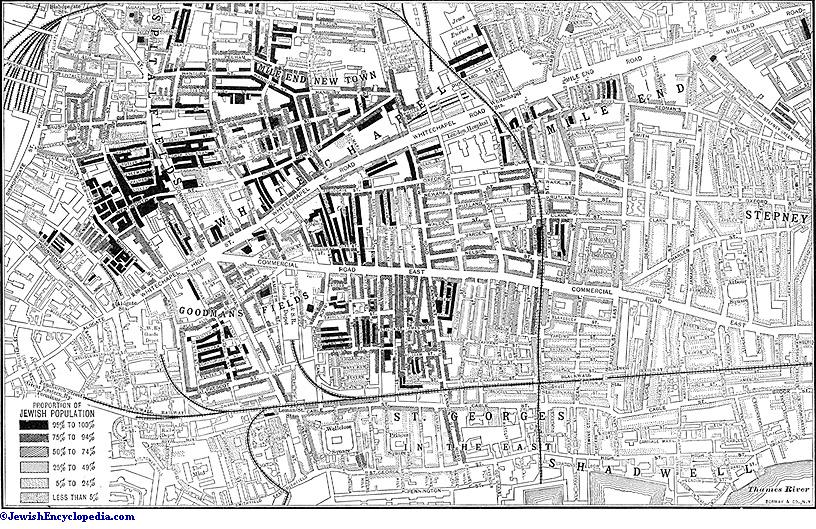

The increased tide of alien immigration became especially noticeable as it was mainly directed into one administrative district of East London, that of Stepney. The overcrowding which already existed in this district was accentuated; and a certain amount of displacement of the native inhabitants took place owing to the excessive rise in rents, producing a system of "key money," by which a bonus was paid by the incoming tenant for the privilege of paying rent. Certain branches of the tailoring, shoemaking, and carpentering trades tended to become monopolized by the Russo-Polish Jews settled in Stepney. Toward the end of the nineteenth century a certain amount of objection began to be raised to this and other tendencies of the immigrants. A special organization known as "The British Brothers' League," headed by Major Evans Gordon, raised an agitation against any further immigration of the kind; and owing in large measure to its clamor, a royal commission was appointed to examine into the alleged effects of unrestricted immigration. Though nominally directed against all aliens, it was almost without disguise applied chiefly to aliens of the Jewish faith. A previous commission, appointed to consider the same in 1889, had decided that the evils, if any, were so insignificant that they did not require any special legislation.

The commission, on which Lord Rothschild sat as member, devoted a considerable amount of attention to the subject, holding forty-nine public meetings mostly with regard to the London Jews of the East End. On the whole, it gave a fairly favorable account of the alien immigrant. He was acknowledged to be fairly healthy and reasonably clean on arrival, thrifty and industrious, and law-abiding. His children were especially bright and assimilative of English ways. It was not proved to the satisfaction of the commission that any severe displacement of labor had been caused by the "greener," who on his part tended to introduce new though less highly efficient methods of production in the clothing and furniture industries. The one true indictment found against the immigrant was that of overcrowding; and the recommendations of the commission were chiefly directed against this. It suggested that any district in which aliens congregated should be declared a prohibited area, and no alien should be admitted thereto for a period of two years after his arrival; and that to insure this all immigrants should be registered. Legislation intended to carry out this and other suggestions was introduced into the British Parliament in 1904. An unfortunate admission of Leonard L. Cohen, president of the Board of Guardians, that his institution found it necessary to send back a certain number of "undesirables," weakened the possible resistance of the London community to the proposal that the repatriation of such undesirables should be undertaken by the government.

Intellectual Progress.During the last quarter of the nineteenth century a certain revival of interest in Jewish literature and history occurred among native London Jews. A small study circle associated with the Rev. A. L. Green in the early part of the seventh decade, and a series of public lectures in connection with Jews' College, gave opportunities for young men of promise to display their ability. These efforts have been more recently seconded by those of Jewish literary societies spread throughout London, and of a Jewish Study Society founded in 1900, mainly in imitation of the American Council of Jewish Women. "The Jewish Quarterly Review," founded by C. J. Montefiore and edited by him and by Israel Abrahams, has gradually become one of the most important scientific journals connected with Jewish science. Both of these gentlemen have been connected from time to time with movements intended to render religious worship more free from traditional trammels. The latest of these movements was that of the Jewish Religious Union in the year 1902, which was eminently a year of unions, as it saw also the formation of the Jewish Literary Societies Union, the Union of Jewish Women, and the Jewish Congregational Union.

One more movement may be referred to as characteristic of the London Jewry. About 1885 a number of the younger intellectual workers in the community were collected around Asher I. Myers, editor of "The Jewish Chronicle," in an informal body; they called themselves "The Wandering Jews," and included S. Schechter, I. Zangwill, Israel Abrahams, Joseph Jacobs, Lucien Wolf, and others. These met for several years in one another's houses for the informal discussion of Jewish topics, and this ultimately led to the foundation of the Maccabæans, an institution intended to keep professional Jews in touch with their coreligionists. This mixing with the outer world while still retaining fellowship with Israel is most characteristic of London, as indeed of the whole of English, Jewry.

Recent immigration has tended to divide London Jewry into two diverse and to a certain extent antagonistic elements; but the experiences and the administrative policy of the past decade have tended to bridge over the gap and reunite the two classes in communal organization. The beginning of the twentieth century finds difficulties similar to those found at the beginning of the nineteenth. Former experience shows that it is within the power of the community to remedy its own shortcomings.

This sketch of the history of the institutions and the prominent men that have made up the London community may be concluded with a list of the latter, from 1700 onward, including many who could not otherwise be specifically referred to. Persons whose date of birth alone is given are still living.

| Name. | Date. | Description. |

|---|---|---|

| Abraham, Abraham | d. 1863 | Author and communal worker. |

| Abrahams, Abraham | 1801-80 | Hebrew writer on sheḥiṭah. |

| Abrahams, Barnett | 1831-63 | Dayyan. |

| Abrahams, Barnett Lionel | b. Dec. 9, 1869. | Communal worker. |

| Abrahams, Israel | b. 1858 | Author and communal worker. |

| Abrahams, Louis Barnett | b. 1842 | Head Master, Jews' Free School. |

| Adler, Elkan Nathan | b. 1861 | Communal worker; bibliophile. |

| Adler, Very Rev. Hermann. | b. May, 1839. | Chief rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the British Empire. |

| Adler, Rev. Michael | b. July 27, 1868. | Minister of Central Synagogue. |

| Adler, Nathan Marcus | 1803-90 | Chief rabbi of England. |

| Aguilar, Ephraim Lopez Pereira, Baron d'. | 1739-1802 | Eccentric and miser. |

| Aguilar, Grace | 1816-47 | Novelist. |

| Alex, Ephraim | 1800-82 | Founder Jewish Board of Guardians. |

| Alexander, Abraham | 1718-86 | Author and printer. |

| Alexander, David L. | b. 1842 | President, Board of Deputies. |

| Alexander, Levy | 1754-1853 ? | Author and printer. |

| Alexander, Lionel L. | 1852-1901 | Honorary Secretary, Board of Guardians. |

| Almeida, Joseph d' | 1716-88 | Stockbroker. |

| Almeida, Manuela Nufiez d'. | fl. c. 1720 | Poetess. |

| Almosnino, Ḥasdai | d. 1802 | Dayyan. |

| Almosnino, Isaac | d. 1843 | Ḥazzan. |

| Almosnino, Solomon | 1792-1878 | Secretary, Bevis Marks Synagogue. |

| Angel, Moses | 1819-98 | Educationist. |

| Ansell, Moses | d. 1841 | Secretary, Great Synagogue. |

| Ansell, Zalman | fl. 1790 | Dayyan. |

| Aria, Mrs. David B. | b. Aug. 11, 1866. | Journalist. |

| Artom, Benjamin | 1835-79 | Haham. |

| Ascher, B. H. | 1812-93 | Rabbi and author. |

| Ascher, Joseph | 1829-69 | Musical composer. |

| Ascher, Simon | 1789-1872 | Ḥazzan. |

| Asher, Asher | 1837-89 | First Secretary, United Synagogue. |

| Avigdor, Elim d' | d. 1895 | Communal worker. |

| Avigdor, Countess Rachel d'. | 1816-96 | Communal worker. |

| Avigdor-Goldsmid, Osmond Elim d'. | ......... | Communal worker. |

| Azevedo, Moses Cohen d'. | d. 1784 | Haham. |

| Ballin, Mrs. Ada Sara | ......... | Journalist. |

| Barnato, B. I. | 1852-97 | Financier. |

| Barnett, A. L. | 1797-1878 | Dayyan. |

| Barnett, Morris | 1800-56 | Dramatist and actor. |

| Baruh, Raphael | d. 1800 | Author. |

| Beddington, Alfred H. | 1835-1900 | Communal worker. |

| Beddington, Ed. Henry | 1819-72 | Communal worker. |

| Beer, Mrs. Rachel | ......... | Journalist. |

| Behrend, Henry | 1828-93 | Physician, author, and communal worker. |

| Belais, Abraham | 1773-1853 | Hebrew author. |

| Belasco, Aby | b. 1797 | Pugilist. |

| Belasco, David (David James). | 1839-93 | Actor. |

| Belisario, Isaac Mendes | d. 1791 | Preacher. |

| Belisario, Miriam Mendes. | d. 1885 | Authoress. |

| Belmonte, Bienvenida Cohen. | fl. c. 1720 | Poetess. |

| Benedict, Sir Julius | 1804-85 | Composer and musician. |

| Benham, Arthur | 1875-95 | Dramatist. |

| Benisch, Abraham | 1811-78 | Hebraist and journalist. |

| Benjamin, David | 1815-93 | Communal worker. |

| Benjamin, Judah Philip | 1811-84 | American statesman and English barrister. |

| Bensusan, Samuel Levy | b. Sept. 29, 1872. | Journalist. |

| Bentwich, Herbert | b. May 11, 1856 | Communal worker. |

| Bernal, Ralph | d. 1854 | Politician and art-collector. |

| Bischoffsheim, Mrs. H. L. | ......... | Communal worker. |

| Blank, Joseph E. | b. 1866 | Communal secretary. |

| Bolaffey, Hananiah | b. 1779 | Hebraist and author. |

| Braham, John | 1774-1856 | Composer and singer. |

| Buzaglo, Abraham | d. 1788 | Inventor and author. |

| Carvajal, Antonio Fernandez de. | d. 1659 | Founder of London Jewish community. |

| Castello, Daniel | 1831-83 | Communal worker. |

| Castello, Manuel | b. Mar. 21, 1827. | Communal worker. |

| Castro, Hananel de | 1794-1849 | Communal worker (Sephardic). |

| Castro, Jacob de | b. 1758 | Comedian. |

| Castro, Jacob de | 1704-89 | Physician and surgeon. |

| Chapman, Rev. John | b. 1845 | Communal worker and educationist. |

| Cohen, Alfred L. | 1836-1903 | Communal worker. |

| Cohen, Arthur | b. 1830 | Communal worker and King's counsel. |

| Cohen, Benjamin Louis | b. 1844 | Member of Parliament. |

| Cohen, Rev. Francis L. | b. Nov. 14, 1862. | Minister, Borough New Synagogue. |

| Cohen, Leonard L. | b. April 17, 1858. | President, Board of Guardians. |

| Cohen, Levy Barent | 1740-1808 | Communal worker. |

| Cohen, Lionel Louis | 1832-87 | Communal worker, financier, and politician. |

| Cohen, Louis Louis | 1799-1882 | Financier. |

| Cohen, Nathaniel Louis | b. 1847 | Communal worker. |

| Cohen, Samuel Isaac | b. Jan. 1, 1861. | Communal secretary. |

| Cortissos, Don José | 1656-1742 | Army contractor. |

| Costa, Benjamin Mendez da. | 1704-64 | Philanthropist. |

| Costa, Emanuel Mendez da. | 1717-91 | Librarian to the Royal Society and scientific writer. |

| Costa, Solomon da | fl. c. 1760 | Donor of Hebrew library to British Museum. |

| Cowan, Phineas | 1832-99 | Public worker. |

| Cowen, Frederic H. | b. Jan. 29, 1852. | Composer and conductor. |

| Dainow, Hirsch | 1832-77 | Maggid. |

| Davids, Arthur Lumley | 1811-32 | Orientalist. |

| Davidson, Ellis Abraham | 1828-78 | Technologist. |

| Davis, David Montague | ......... | Composer. |

| Davis, Felix Arthur | b. Aug. 14, 1863. | Communal worker. |

| Davis, Frederick | 1843-1900 | Antiquary. |

| Davis, Israel | b. 1847 | Proprietor "Jewish Chronicle." |

| Davis, James | ......... | Playwright and journalist. |

| Davis, Maurice | 1821-98 | Physician and communal worker. |

| Davis, Myer David | b. 1830 | Anglo-Jewish historian. |

| Delpini, Carlo Anton | d. 1828 | Clown and theatrical manager. |

| Deutsch, Emanuel Oscar | 1831-73 | Orientalist. |

| Disraeli, Benjamin, Earl of Beaconsfield | 1804-81 | Statesman. |

| D'Israeli, Isaac | 1766-1848 | Author. |

| Dolaro, Selina | 1852-89 | Actress. |

| Dupare, M. | b. 1852 | Secretary, Anglo-Jewish Association. |

| Dyte, D. M. | fl. c. 1800 | Saved life of George III. |

| Eichholz , Alfred | b. Nov. 26, 1869. | Educationist. |

| Eisenstadt, Jacob | fl. c. 1770 | Author of "Toledot Ya'aḳob." |

| Eliakim b. Abraham | fl. c. 1794 | Hebrew author. |

| Elias, Samuel ("Dutch Sam"). | 1775-1816 | Pugilist. |

| Ellis, Sir Barrow Helbert. | 1823-87 | Indian statesman. |

| Emanuel, Barrow | 1842-1904 | Communal worker. |

| Emanuel, Charles Herbert Lewis. | b. Jan. 10, 1868. | Secretary, Board of Deputies. |

| Emanuel, Frank L. | b. 1866 | Artist. |

| Emanuel, Joel | d. 1842 | Philanthropist. |

| Emanuel, Lewis | 1832-98 | Secretary, Board of Deputies. |

| Emanuel, Walter L. | b. 1869 | Litterateur. |

| Evans, Samuel ("Young Dutch Sam") | 1801-43 | Pugilist. |

| Falk, Hayyim Samuel Jacob "Ba'al Shem"). | 1708-82 | Cabalist. |

| Farjeon, B. L. | 1833-1903 | Novelist. |

| Faudel, Henry | d. 1863 | Worker for emancipation. |

| Faudel-Phillips, Sir George, Bart. | b. 1840 | Communal worker. |

| Fay, Rev. David | b. April, 1854. | Minister, Central Synagogue. |

| Fernandez, Benjamin Dias. | c. 1720 | Author. |

| Franklin, Ellis A. | b. Oct., 1822 | Communal worker. |

| Franklin, Ernest Louis | b. Aug. 16, 1859. | Communal worker. |

| Franklin, Jacob Abraham | 1809-77 | Journalist and philanthropist. |

| Freund, Jonas | d. 1880 | Physician and founder of the German Hospital. |

| Friedländer, Michael | b. April 29, 1833. | Principal, Jews' College. |

| Gaster, Anghel | b. 1863 | Physician. |

| Gaster, Very Rev. Moses. | b. 1856 | Haham of the Spanish and Portuguese Congregation. |

| Gideon Samson | 1699-1762 | Financier. |

| Goldsmid, Abraham | 1756-1810 | Financier and philanthropist. |

| Goldsmid, Albert Edward W. | 1846-1904 | Colonel; communal worker and Zionist. |

| Goldsmid, Anna Maria | 1805-89 | Authoress and communal worker. |

| Goldsmid, Benjamin | 1755-1808 | Financier and philanthropist. |

| Goldsmid, Sir Francis, Bart. | 1808-78 | Philanthropist and politician. |

| Goldsmid, Sir Isaac Lyon, Bart. | 1778-1859 | Financier and philanthropist. |

| Goldsmid, Sir Julian | 1838-96 | Communal leader. |

| Goldstücker, Theodor | 1821-72 | Professor of Sanskrit, King's College. |

| Gollancz, Rev. Hermann. | b. Nov.30, 1852. | Professor of Hebrew, University College. |

| Gollancz, Israel | b. 1864 | Secretary, British Academy. |

| Gollancz, S. M. | 1822-1900 | Ḥazzan. |

| Gompertz, Benjamin | 1779-1865 | Actuary and mathematician. |

| Gompertz, Ephraim | fl. 1860 | Economist and mathematician. |

| Gompertz, Isaac | 1774-1856 | Poet. |

| Gompertz, Lewis | d. 1861 | Founder of "Animals' Friend." |

| Goodman, Edward John | b. Dec. 19, 1836. | Journalist. |

| Goodman, Tobias | fl. 1834 | Preacher and author. |

| Gordon, Lord George | 1751-93 | Convert to Judaism. |

| Gordon, Samuel | b. September, 1871. | Novelist. |

| Green, Rev. A. A. | b. 1860 | Minister, Hampstead Synagogue. |

| Green, Rev. Aaron Levy | 1821-83 | Minister and preacher. |

| Greenberg, L. J. | ......... | Communal worker and Zionist. |

| Guedalla, Henry | b. c. 1820 | Communal worker. |

| Guedalla, Judah | 1760-1858 | Moroccan merchant and philanthropist. |

| Harris, Henry | 1819-99 | Communal worker. |

| Harris, Rev. Isidore | b. June 6, 1853. | Minister, West London Synagogue of British Jews. |

| Hart, Aaron | 1670-1756 | Chief rabbi. |

| Hart, Ernest | 1836-98 | Physician. |

| Hart, Moses | d. 1756 | Founder of Duke's Place Synagogue. |

| Hart, Solomon Alexander. | 1806-81 | Artist. |

| Hartog, Cécile Sarah | ......... | Musician. |

| Hartog, Numa Edward | 1846-71 | Senior wrangler. |

| Henriques, David Quixano | 1804-76 | Prominent reformer. |

| Henry,Emma | 1788-1870 | Poetess. |

| Henry, Michael | 1830-75 | Journalist and mechanician. |

| Herschell, Solomon | 1762-1842 | Chief rabbi. |

| Hirsch, S. A. | ......... | Hebraist and journalist. |

| Hirschfeld, Hartwig | ......... | Arabist. |

| Hurwitz, Hyman | 1770-1844 | Professor of Hebrew and author. |

| Hyams, Henry H. | b. 1852 | Communal secretary. |

| Isaac, Benjamin | d. 1750 | Founder of Hambro' Synagogue. |

| Isaac, Samuel | 1812-86 | Promoter of the Mersey tunnel. |

| Isaacs, Sir Henry Aaron. | b. Aug. 15, 1830. | Municipal worker; lord mayor. |

| Isaacs, Rufus D. | ......... | King's counsel. |

| Jackson, Harry | 1836-85 | Actor. |

| Jacobs, Joseph | 1813-70 | Wizard and prestidigitator. |

| Jessel, Albert Henry | b. Oct. 31, 1864. | Communal worker. |

| Jessel, Sir Charles James, Bart. | b. May 11, 1860. | Director of public companies. |

| Jessel, Right Hon. Sir George | 1824-83 | Master of the rolls. |

| Joseph, Delissa | b. 1859 | Communal worker; architect. |

| Joseph, Rev. Morris | b. 1848 | Senior delegate minister, West London Synagogue. |

| Joseph, N. S. | b. 1834 | Communal worker; architect. |

| Josephs, Michael | 1763-1849 | Hebraist. |

| Kalisch, Marcus M. | 1828-85 | Hebraist and Bible commentator. |

| Keeling, Henry I. | 1805-80 | Philanthropist. |

| Keizer, Moses | 1831-93 | Ḥazzan. |

| Ḳimḥi, Jacob | 1720-1800 | Hebraist and pedler. |

| King, John | d. 1824 | Author. |

| Kohn-Zedek, Joseph | 1827-1904 | Hebraist. |

| Laguna, Daniel Israel | 1660-1720 | Hebraist and poet. |

| Lamego, Moses | fl. 1757 | Philanthropist. |

| Landau, Hermann | b. 1844 | Communal worker. |

| Landeshut, Samuel | 1825-77 | Secretary, Board of Guardians. |

| Lara, Isidore de | b. Aug. 9, 1858. | Musician. |

| Lasker, Emanuel | b. Dec. 24, 1868. | Chess champion of the world. |

| Laurence, John Zechariah | 1828-70 | Ophthalmic surgeon and author. |

| Lawson, Lionel | 1823-79 | Newspaper proprietor. |

| Lee, Sidney | b. Dec. 5, 1859. | Author and Shakespearean scholar. |

| Leon, Hananel de | fl. c. 1821 | Physician. |

| Levetus, Celia | d. 1873 | Authoress. |

| Levi, David | 1742-1801 | Hebraist and author. |

| Levisohn, George (Gompertz). | d. 1797 | Surgeon and author. |

| Levy, Abraham | b. Sept. 7, 1848. | Educationist and communal worker. |

| Levy, Amy | 1862-89 | Poetess and novelist. |

| Levy, Benjamin | fl. 1750 | Financier. |

| Levy, Jonas | d. 1894 | Vice-chairman, London and Brighton Railway. |

| Levy, Joseph Hiam | b. July 17, 1838. | Political economist. |

| Levy, Joseph Moses | 1812-88 | Proprietor of "Daily Telegraph." |

| Levy, Rev. Solomon | b. 1872 | Minister, New Synagogue. |

| Lewis, Sir George Henry | b. April 21, 1833. | Solicitor. |

| Lewis, Harry S. | b. 1861 | Communal worker. |

| Lewis, James Graham | d. 1873 | Solicitor. |

| Liebreich, Richard | b. June 30, 1830. | Surgeon and ophthalmologist. |

| Lindo, Abigail | 1803-48 | Hebrew lexicographer. |

| Lindo, Algernon | b. 1863 | Musician. |

| Lindo, David Abarbanel | 1765-1851 | Communal worker. |

| Lindo, Elias Haim | 1783-1865 | Jewish historian. |

| Lindo, Frank | b. Oct. 30, 1865. | Actor. |

| Lindo, Gabriel | b. July, 1839. | Communal worker. |

| Lindo, Moses Albert Norsa | b. April 27, 1862. | Communal worker. |

| Loewe, James H. | b. 1852 | Communal worker. |

| Loewe, Louis | 1809-88 | Orientalist; first principal Judith Monteflore College. |

| Lopez, Sir Manasseh, Bart. | d. 1831 | Politician. |

| Löwenthal, J. J. | 1810-76 | Chess-player. |

| Löwy, Rev. Albert | b. December, 1816. | Communal worker. |

| Lucas, Alice (Mrs. Henry Lucas). | ......... | Authoress and communal worker. |

| Lucas, Sampson | 1821-79 | Communal worker. |

| Lumley, Benjamin | 1811-75 | Theatrical director. |

| Lyon, George Lewis | 1828-1903 | Journalist and communal worker: editor, "Jewish World." |

| Lyon, Hart | 1721-1800 | Chief rabbi. |

| Maas, Joseph | 1847-86 | Musician and singer. |

| Magnus, Lady | b. 1844 | Authoress and communal worker. |

| Magnus, Laurie | b. Aug. 5, 1872. | Author and journalist. |

| Magnus, Sir Philip | b. Oct. 7, 1842. | Educationist and communal worker. |

| Marks, B. S. | ......... | Artist and communal worker. |

| Marks, David Woolf | b. Nov. 22, 1811. | Chief minister, West London Synagogue. |

| Marks, Harry Hananel | b. 1855 | Member of Parliament; journalist; "Financial Times." |

| Medina, Sir Solomon de | fl. 1711 | Army contractor. |

| Meldola, David | 1797-1853 | Dayyan. |

| Meldola, Raphael | 1754-1828 | Haham. |

| Meldola, Raphael | b. July 19, 1849. | Chemist. |

| Mendes, Abraham | fl. 1718 | Thieftaker. |

| Mendez, Moses | d. 1758 | Banker and poet. |

| Mendoza, Daniel | 1763-1836 | Champion pugilist. |

| Merton, Louis | 1840-74 | Financier. |

| Meyers, Barnett | 1814-89 | Communal worker. |

| Middleman, Judah | fl. 1847 | Hebrew author. |

| Mocato, Moses | fl. 1677 | Merchant and author. |

| Mocatta, Abraham | 1797-1880 | Communal worker. |

| Mocatta, Abraham Lumbrozo de Mattos | 1730-1800 | Merchant and communal worker. |

| Mocatta, A. de Mattos | 1853-91 | Communal worker. |

| Mocatta, Frederick David | b. Jan. 15, 1828. | Philanthropist. |

| Mocatta, Jacob | 1770-1825 | Communal worker. |

| Mocatta, Moses | 1768-1857 | Author. |

| Mombach, Julius (Israel) Lazarus | 1813-80 | Musician and composer. |

| Mond, Ludwig | b. March 7, 1839. | Chemist. |

| Montagu, Hyman | 1845-95 | Numismatist. |

| Montagu, Sir Samuel, Bart. | b. 1832 | Communal worker. |

| Monteflore, Claude G. | b. 1858 | Author and communal worker. |

| Monteflore, Sir Francis Abraham, Bart. | b. Oct. 10, 1860. | Communal worker and Zionist. |

| Monteflore, Horatio | 1798-1867 | Communal worker. |

| Monteflore, Joseph Barrow. | 1803-93 | Communal worker. |

| Monteflore, Joseph Mayer | 1816-80 | Communal worker. |

| Monteflore, Sir Joseph Sebag. | 1822-1901 | Communal worker. |

| Monteflore, Judith, Lady | 1784-1862 | Philanthropist. |

| Monteflore, Leonard | 1853-79 | Author. |

| Monteflore, Sir Moses, Bart. | 1784-1885 | Philanthropist. |

| Mosely, Alfred | b. 1855 | South-African pioneer. |

| Moses, Joseph Henry | 1805-75 | Philanthropist. |

| Myers, Asher I. | 1848-1902 | Journalist and communal worker. |

| Neumegen, Leopold | 1787-1875 | Schoolmaster. |

| Newman, Alf. Alvarez | 1851-87 | Metal-worker and art-collector. |

| Newman, Selig | 1788-1871 | Hebraist and teacher. |

| Nieto, David | 1654-1728 | Haham. |

| Nieto, Isaac | d. 1755 | Haham. |

| Nonski, Abraham | fl. 1785 | Hebrew writer on vaccination. |

| Oppenheim, Morris Simeon. | d. 1882 | Barrister. |

| Pacifico, Emanuel | ......... | Founder of almshouses. |

| Palgrave, Sir Francis Cohen | 1788-1861 | Historian. |

| Pereira, Jonathan | 1804-53 | Physician. |

| Phillips, Sir Benjamin | 1811-89 | Lord mayor of London. |

| Picciotto, James | 1830-97 | Anglo-Jewish historian. |

| Picciotto, Moses Haim | 1806-79 | Communal worker. |

| Pimentel, Abraham Jacob Henriques. | fl. 1720 | Author. |

| Pimentel, Sara de Fonseca y. | fl. 1720 | Poetess. |

| Pinto, Thomas | d. 1773 | Violinist. |

| Pirbright, Baron | 1840-1902 | Member of Parliament. |

| Price, Julius Mendes | ......... | Artist; journalist; traveler. |

| Pyke, Joseph | 1824-1902 | Communal worker. |

| Pyke, Lionel E. | 1855-99 | Queen's counsel. |

| Raphall, Morris Jacob | 1798-1868 | Preacher and author. |

| Rausuk, Samson | 1793-1877 | Hebrew poet. |

| Rebello, David Alves | d. 1796 | Merchant and numismatist. |

| Ricardo, David | 1772-1823 | Economist and politician. |

| Rintel, Meïr | fl. 1817 | Hebrew author. |

| Rosebery, Lady | 1851-90 | Political and social leader. |

| Rothschild, Sir Anthony de, Bart. | 1810-76 | Financier and communal worker. |

| Rothschild, Baroness Charlotte de. | 1836-84 | Philanthropist. |

| Rothschild, Baron Ferdinand de. | 1839-98 | Philanthropist; member of Parliament. |

| Rothschild, Lord | b. Nov. 8, 1810. | Communal worker. |

| Rothschild, Baroness Hannah de. | 1782-1850 | Communal worker. |

| Rothschild, Baroness Juliana de. | d. 1877. | Philanthropist. |

| Rothschild, Lady | ......... | Communal worker. |

| Rothschild, Leopold de | b. 1845 | Communal worker. |

| Rothschild, Baron Lionel de. | 1808-79 | Financier and politician. |

| Rothschild, Hon. Lionel Walter. | b. Feb. 8, 1868. | Communal worker; Member of Parliament. |

| Rothschild, Baron Mayer de. | 1818-74 | Financier and sportsman. |

| Rothschild, Baron Nathan Mayer. | 1777-1836 | Financier. |

| Russell, Henry | 1813-1900 | Composer and singer. |

| Salaman, Chas. Kensington | 1814-1901 | Musician. |

| Salaman, Malcolm Charles | b. Sept. 6, 1855. | Author and journalist. |

| Salomons, Annette A. | d. 1879 | Authoress. |

| Salomons, Sir David, Bart. | 1797-1873 | Lord mayor and politician. |

| Salomons, Sir David Lionel, Bart. | b. June 28, 1851. | Engineer. |

| Salomons, Levi | 1774-1843 | Financier. |

| Salvador, Joseph | fl. 1753 | Philanthropist. |

| Samuda, Isaac de Sequera. | fl. 1721 | Physician. |

| Samuda, Jacob | 1811-74 | Civil engineer. |

| Samuda, Joseph d'Aguilar | 1813-84 | Politician and shipbuilder. |

| Samuel, Baron Denis Moses de. | 1782-1860 | Financier. |

| Samuel, Charles | 1821-1903 | Communal worker. |

| Samuel, Sir Harry S. | b. 1853 | Member of Parliament; communal worker. |

| Samuel, Herbert | b. 1870 | Member of Parliament. |

| Samuel, Sir Marcus, Bart | b. 1853 | Lord mayor of London. |

| Samuel, Moses | 1795-1860 | Author. |

| Samuel, Sampson | 1804-68 | Secretary to the Board of Deputies. |

| Samuel, Stuart M. | b. 1856 | Member of Parliament; communal worker. |

| Samuel, Sydney M. | 1848-84 | Author. |

| Samuels, Moses | fl. 1830 | Biographer of Mendelssohn. |

| Sarmento, Jacob de Castro. | 1692-1762 | Physician. |

| Sassoon, Sir Albert | 1818-97 | Anglo-Indian merchant and philanthropist. |

| Schiff, David Tebele | d. 1792 | Chief rabbi. |

| Schloss, David Frederick | b. 1850 | Communal worker. |

| Schloss, Leopold | b. Nov. 5, 1824. | Communal worker. |

| Sebag, Solomon | 1828-92 | Hebrew teacher. |

| Seligman, Isaac | b. Dec. 2, 1834. | Communal worker. |

| Semon, Sir Felix | b. Dec. 8, 1849. | Laryngoscopist. |

| Sequera, Isaac Henriques | 1738-1816 | Physician. |

| Serra, Isaac Gomes | d. 1818 | Philanthropist. |

| Simon, Sergeant Sir John | 1818-97 | Communal worker, lawyer, and politician. |

| Simon, Oswald John | b. Sept. 3, 1855. | Communal worker. |

| Singer, Rev. Simeon | b. 1848 | Minister, New West End Synagogue. |

| Sloman, Charles | 1808-70 | Musical composer and improvisator. |

| Sloman, Henry | 1793-1873 | Actor. |

| Snowman, Isaac | b. 1874 | Artist. |

| Sola, Abraham de | 1825-52 | Preacher; professor of Hebrew. |

| Sola, Samuel de | 1839-66 | Ḥazzan. |

| Solomon, Abraham | 1824-62 | Artist. |

| Solomon, Henry Naphtali | 1796-1881 | Educationist and Hebraist. |

| Solomon, Selim | b. April 28, 1843. | Secretary, West London Synagogue of British Jews; communal worker. |

| Solomon, Solomon Joseph | b. Sept. 16, 1860. | Artist. |

| Spielmann, Isidore | b. July 21, 1854. | Communal worker. |

| Spielmann, Marion H. | b. May 22, 1858. | Author and publicist. |

| Stern, David, Viscount de | d. 1877 | Financier. |

| Stern, Sir Edward David | b. c. 1860 | Communal worker. |

| Stern, Baron Hermann de | 1815-87 | Financier. |

| Stern, Rev. J. F. | b. Jan. 2, 1865. | Minister, East London Synagogue. |

| Strauss, Gustave Lewis Maurice | 1807-87 | Author. |

| Suasso, Isaac (Antonio) Lopez, Baron Avernes de Gras | 1693-1775 | Financier. |

| Sydney, Algernon Edward | b. Jan. 8, 1834. | Solicitor and communal worker. |

| Sylvester, J. J. | 1814-97 | Mathematician; professor. |

| Symons, Baron Lyon de | fl. 1800 | Communal worker. |

| Tuck, Adolf | ......... | Communal worker. |

| Valentine, Nathan Isaac | fl. 1806 | Hebrew author. |

| Van Oven, Barnard | 1797-1860 | Physician. |

| Van Oven, Joshua | 1766-1838 | Surgeon. |

| Van Strahlen, Samuel | b. 1845 | Hebrew librarian, British Museum. |

| Villa Real, Isaac da Costa | d. 1730 | Founder of Villa Real School. |

| Villiers, John Abraham Jacob de. | b. 1863 | Writer and communal worker. |

| Waley, Jacob | 1819-73 | Conveyancer; professor of political economy. |

| Wandsworth, Baron | b. 1845 | Politician. |

| Wasserzug, H. | d. 1882 | Ḥazzan and composer. |

| Wolf, Lucien | b. Jan. 20, 1857. | Journalist and Anglo-Jewish historian. |

| Wolff, Joseph | 1795-1862 | Traveler and Christian missionary. |

| Worms, Baron de | b. Feb. 16, 1829. | Politician. |

| Worms, Maurice Benedict de. | 1805-67 | Financier. |

| Worms, Baron Solomon de | 1801-82 | Financier. |

| Ximenes, Sir Morris | b. 1762 | Financier. |

| Zangwill, Israel | b. 1864 | Man of letters. |

| Zangwill, Louis | b. 1869 | Novelist. |

| Zedner, Joseph | 1804-71 | Hebraist. |

| Zimmer, N. L. D. | 1831-95 | Hebraist and cabalist. |

| Zukertort, J. H. | 1842-88 | Chess-player. |

It is possible to ascertain with some accuracy the Jewish population of London owing to the fact that statistics of Jewish deaths and marriages have been recorded with some completeness by the United Synagogue and the Board of Deputies for the last thirty years. To the information from these sources may be added the reports of the number of Jewish children attending the Jewish schools, given by Jacobs and Harris in successive issues of the "Jewish Year Book" with ever-increasing fulness. The following table gives these data at intervals of five years for the last thirty years:

| Year. | Deaths. | Marriages. | School-Children. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1873 | 847 | 331 | .... |

| 1878 | 985 | 377 | .... |

| 1883 | 959 | 381 | 7,383 |

| 1888 | 1,129 | 589 | .... |

| 1893 | 1,792 | 788 | 15,964 |

| 1898 | 1,765 | 1,096 | 19,442 |

| 1902 | 2,233 | 1,478 | 31,515 |

From the last-given data the number of Jews in London in the middle of 1902 can be ascertainedwith some degree of probability. The general death-rate of London for the year 1902 was 17.6 per thousand, but since the Jewish population is composed so largely (three-quarters as against one-half in the general London population) of young men and women of the most viable ages, 15-60, it is unlikely that the death-rate was higher than 15 per thousand (the same as that in the Jewish quarter of the borough of Stepney in 1901). This would give a Jewish population in London of 148,866 in 1902, an estimate which is confirmed by the number of marriages, 1,478, which, at 10 per thousand—a very high rate indeed—would give 147,800. The number of school-children, however, would point to an even higher total. Of these, 31,515, out of a total of 761,729, were in board and voluntary schools. If the proportion of school-children to population held with regard to the Jewish children as to the total population (4,536,541) within the school board area, this would imply a Jewish population of about 187,427. But these statistics are for a year later than that of the death-rate figures quoted above, and besides it is probable that more Jewish children are entered on the school-books, and more of those entered attend, than with the general population, so that the figures are somewhat misleading. Altogether it is likely that the Jewish population of London in the middle of 1902 was about 150,000, of whom at least 100,000 were in the East End of London, half of these being in the borough of Stepney ("Alien Immigration Commission," iii. 90). Of the remainder the majority are well-to-do residents in the Maida Vale, Bayswater, and Hammersmith districts, though subordinate ghettos have been created in Soho and Southwark. From the above-cited figures it would seem probable that the London Jewish population trebled during the years between 1883 and 1902. Part of this increase is doubtless due to the excess of births over deaths and to migration from the provinces, but at least 50,000 have been added by foreign immigration during that period, an average of 2,500 per annum.

Synagogues.This increase has been met by a corresponding increase in the number of seat-holders in the London synagogues—2,289 in 1873; 3,397 in 1883; 5,594 in 1893; and 9,556 in 1902. Altogether there are 65 synagogues to meet the religious needs of the Jews of London; of these 15 belong to the United Synagogue. They are as follows, with the number of their seat-holders and their income for 1902, and are arranged in the order of their reception within the ranks of the United Synagogue:

| Synagogue. | Total Income. | Seats Let. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Great | £2,923 | 437 | |

| Hambro' | 489 | 200 | |

| New | 1,458 | 302 | |

| Bayswater | 4,259 | 363 | |

| Central | 3,710 | 350 | |

| Borough | 794 | 178 | |

| St. John's Wood | 3,020 | 378 | |

| East London | 1,202 | 353 | |

| North London | 1,318 | 187 | |

| New West End. | £4,613 | 320 | |

| Dalston | 2,186 | 361 | |

| Hammersmith | 934 | 211 | |

| Hampstead | 4,896 | 464 | |

| South Hackney | 1,190 | 354 | |

| Stoke Newington | 800 | .... | |

| Total | £33,792 | 4,458 | |