Reed Organ

From Nwe

From Nwe The reed organ is a keyboard instrument that operates via bellows that blow wind past free-floating reeds. A free floating reed doesn’t change pitch by increasing or decreasing the wind pressure and is, therefore, ideal to express dynamics by the pumping/pedaling action of the feet. The faster a player pumps, the louder the reed organ gets, and vice versa. It is also known by the names of harmonium, pump organ, parlor organ, melodeon, seraphine, lap organ, psalmenpomp, Physharmonica, Zungenorgel, Cottage Organ, House Organ, Æoline, Æelodicon, Aérophone, Mélophone, Mélodion, Organino, and others.

Technical details

Most pressure wind type reed organs were built in Europe, although the American builder Aeolian made many Vocalion models with two manuals and an independent pedal with its own keyboard. Suction type organs were mainly built in the United States, but European makers later followed as well. Since they were less expensive to build, lighter than pianos, and didn’t need tuning, many found their way well outside Europe and North America. They were also popular in homes and businesses since these were instruments that reminded people of church organs or keyboard instruments in popular singing groups.

Reed organs, or American organs, as they are called in the United States, became very popular, and many factories sprung up in the second half of the nineteenth century when these instruments were mass-produced.

Original invention by Kratzenstein for scientific research

The free floating reed was developed in 1778, by Christian-Gottlieb Kratzenstein (1723-1795) as part of a plan to construct a human speech machine that could mimic the vowels of human speech for scientific research. Kratzenstein, thus, sent a small two-octave reed instrument to the Academy of Science in St. Petersburg. He may have worked together with organ builder Franz Kirschnick and his assistant, Georg Christoffer Rackwitz. Kirschnick then decided independently to use these kinds of reeds in his instruments, such as the pianoforte/organ combinations (called claviorganum), and possibly in an instrument called the "orchestrion," an automatic player or barrel type organ, around 1781. This was the first time that free floating reeds were employed as a new kind of organ stop. As far as is known, it was not applied to any classic pipe or church organ. Soon, builders in St. Petersburg, like Johann Gabrahn, started to make "claviorganums." The news of this new type of instrument quickly spread to Germany, where, possibly among others, Strohmann and Abbe Vogler further developed these types of instruments.

Early developments

The tremendous dynamic range of the reeds with windpressure, from very soft and nearly inaudible (a feature not possible with classic pipe organ reeds) to quite loud, mimicked the dynamic range of the then still new pianoforte as an organ. This type of dynamic was exactly what performers and composers were looking for, and the music of Beethoven and Berlioz testify to the new kind of massive dynamic range approaches that were becoming very popular.

In 1810, Gabriel Joseph Grenié of Paris applied for a patent for his “orgue expressif” and was thus the first to introduce the reed organ in his country. Apparently, he had seen an instrument built by Kratzenstein 30 years earlier at a friend’s house, around 1770, which led to his own application of the operating principle. This may have been the one Kratzenstein sent to the Academy in St. Petersburg, which was consequently sent to someone in France. Another countryman, Sébastian Érard, also experimented with free reeds. In 1814, Eschenbach of Königshoven in Bavaria invented a keyboard with vibrators, called the "Oragno-Violine." In 1816, Schlimbach of Ohrdurf improved it and called it the "AEoline." A continuous wind instrument was made by Voit of Schweinfurt in 1817, and he named it the "AEolodicon." In 1818, Anton Häckel of Vienna, built a diminutive AEoline used co-jointly with a pianoforte, and called it the "Physharmonica," which apparently caused quite a stir. Professor Payer took this bellows-harmonica with him to Paris in 1823, and several imitations of it were made, such as the "Aerophone" by Christian Dietz, in 1829. In 1836, Fourneaux may have made a 16 foot or octave deep register, and in 1837, an instrument was created which was called a "Melophone." Many builders started to make similar instruments, adding their own improvements and inventions to them, and called them by a large variety of names, such as Aeolidon (which had bent tongues), Adelphone, Adiaphonon, Harmonikon, Harmonine, Melodium, Aeolian, Panorgue, Poikolorgue, Seraphine (in the UK, it was called a keyboard harmonica, but not a harmonium, as it didn’t have channels for the tongues/reeds).

In 1832, Aristide Cavaille-Coll, who later became a world famous pipe organ builder, decided to live for awhile in Toulouse to study mathematics. When Rossini came to this city to present the opera "Robert le Diable," Aristide got an extraordinary chance to demonstrate and explain his recent invention to this famous musician. This instrument, named "Poikilorgue" (varying organ), was a variation of the harmonium which produced an effect of "expression" (crescendo, decrescendo, and so on) with a single set of free floating reeds and a single set of bellows driven by a foot pedal. It had another foot pedal which did not drive the bellows but compressed and regulated the reservoir of air which was connected to them. Surprised with the intelligence and imagination of the young Aristide, Rossini suggested strongly that he go to Paris, the capital of France and a stronghold for new music. Rossini was kind enough to write some letters of introduction to the eminent persons in the capital, and Aristide got started for Paris in 1833, with his elder brother Vincent and his father Dominique. Without the help of Rossini, Aristide Cavaille-Coll may not have become as famous as he eventually did.

Around 1837, in England, Kirkman & White of London started to build small pressure-winded predecessors of the harmonium, and called it a Seraphine. One surviving sample has a single set of reeds within a mahogany case. One of its two pedals supplies the air pressure while the second operates a muting device. Its reeds generate sounds rather slowly and its wind system is difficult to operate smoothly.

Alexandre, who would also become a major builder in France, invented a major improvement in the dynamic range of the instrument, called the "expression."

Builders all over Europe invented many types of methods to make improvements to his basic concept of the harmonium.

In the United States around this time saw the beginnings of reed organs, as several builders in the New England region started to make small lap organs with free-floating reeds, which operated on wind pressure as well.

Application in pipe organs

Although the application of these type of reeds were guaranteed in the manufacture of the American reed organs, both of wind pressure and wind suction types, they were also employed by church organ builders in Germany, especially in the period from 1860-1890. Examples of European builders were Walker, Ladegast en Steinmeier who employed them, Mutin and Merklin after Cavaille-Coll in France, Swiss builders like Rinckenbach, Stiehr and Callinet in the Elzas (their 16 foot pedal stops, called "Ophicleide" instead of "Posaune"), Belge builders such as Schijven and Loret who made the reed organ so popular in Belgium, and the Van Dam firm, F.C. Smits, Van Oekelen, and Kam in the Netherlands. These instruments fell into disfavor at the Advent of the Organ Reform Movement and the Neo-Baroque movement that followed it, but have become popular again since the late twentieth century. In all these cases, the construction was like the typical organ reed: A shallot, a resonator box, and a resonator shallot.

Some organs (known examples exist in Germany, Holland and Switzerland) also have harmonium stops whereby the construction is just as in a harmonium and work with wind pressure. They have no resonator boxes nor shallots.

Other applications

Early free floating reed instruments did not always have a keyboard, but buttons to activate certain pitches. They were small, and this consequently led to the invention of a portable instrument with multiple fold bellows and reeds which would enable the development of sounds when the air was rushing in or out. This led to the development of the modern accordion which also became extremely popular worldwide and still flourishes today. Accordions have either keyboards or pushbuttons, and are still constructed today around the world as a form of light entertainment and in classical performance. The accordion is most often associated with the polka, but there are many more musical forms that are popular.

Free reeds

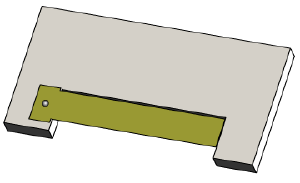

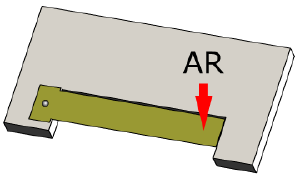

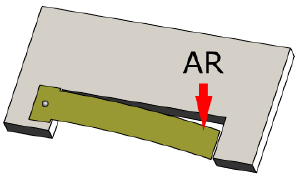

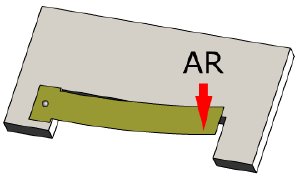

The following illustrations depict the type of reed typical of harmonicas, accordions and reed organs as it goes through a cycle of vibration. One side of the reed frame is omitted from the images for clarity; in actuality, the frame surrounds the reed on four sides.

| A reed is fixed by one end in a close-fitting frame. | |

| Air pressure is applied; the reed prevents air flow, except for a small, high velocity flow at the tip. | |

| The reed is drawn through the opening, allowing the air to pass. | |

| The elasticity of the reed forces it back through the frame. |

Each time the reed passes through the frame, it interrupts air flow. These rapid, periodic interruptions of the air flow initiate the audible vibrations perceived by the listener.

In a free-reed instrument, it is the physical characteristics of the reed itself, such as mass, length, cross-sectional area and stiffness, that primarily determine the pitch (frequency) of the musical note produced. Of secondary importance to the pitch are the physical dimensions of the chamber in which the reed is fitted, and of the air flow.

Why reed organs became very popular

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, with the advent of the pianoforte (the name of this piano already expresses its dynamic range, from soft to loud), as well as the symphonies written in the Rococo and Classical Period, the need for instant dynamic range in an instrument grew tremendously. This created one of the reasons why the harpsichord soon fell into disfavor. Never before had an organ in the home been affordable, let alone one with a dynamic range. Thus there existed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many small pipe organs in many affluent homes. Yet, even to the affluent, these were expensive, heavy, not maintenance-free, and they took up a lot of space.

The reed organ also was a favorite over a piano for small churches which could not afford a pipe organ. In the nineteenth century in the United States, many small churches were built and the reed organ was favored, especially with congregational singing.

In addition, it was preferred for home music-making alongside the piano and in much later times in the cinema and movie theaters as a means of musical interludes and interpretation prior to sound films.

The Estey story

The Estey firm was founded in 1846, by Jacob Estey in Brattleboro, Vermont. This firm made reed organs from 1850 till 1955, and was the company that outlasted all other American companies and made more organs than anyone else. Their factory grew to a large complex of more than 8 buildings. Around 500,000 reed organs were produced in total. The instruments ranged from small portable field organs which were popular with chaplains in wars (used until the Korean War) to large 2-manual and pedal reed organs, which had to be pumped by an assistant, for use in small churches, chapels and larger homes. Estey's reed organs were of sound musical and construction quality and many can still be found worldwide.

While continuing to build reed organs, they also engaged the Roosevelt-trained Philadelphia pipe organ builder, William E. Haskell (1865-1927), to open a pipe organ department in 1901. During the next fifty-nine years, the company built and rebuilt 3261 pipe organs, and with one exception, all of the Estey instruments had tubular-pneumatic or electro-pneumatic action. Many of these organs found their way into large estate homes.

Official instrument for the new Japanese elementary public schools

According to the Reed Organ Club Japan, founded in August 1996, the history of the reed organ in Japan goes back to the 1860s, when reed organs were being introduced by Christian missionaries for use in church services. The Yamaha piano builder was one of the pioneers in Japan to build reed organs. The elementary school education system in Japan was started in 1872. Later, the government of modern Japan chose the reed organ as the official instrument to accompany singing during the obligatory music classes. Other builders followed after Yamaha, such as Nishikawa and Kawai.

The reed organ also became the leading spirit of Japanese modern music called "Shoka" and prepared for music education in elementary schools. Both pupils and teachers had to become familiar with western music, whose tonal and harmonic structures were not earlier known. The American protestant church hymn service (unison singing accompanied by a reed organ) is believed to have been the model for Japanese modern music. A series of hymn melodies were chosen and given new Japanese texts (that is, to praise the Emperor, admire the splendor of nature, and so on). A new generation of Japanese composers like Rentaro Taki, Kousaku Yamada, and others seemed strongly influenced by Shoka and used the reed organ to compose and enrich the repertoire of "Shoka." Japanese language also met a turning point in style. Leading poets eagerly wrote the texts for the "Shoka" melodies. In this way, "Shoka" became one of the highest points of Japanese music repertoire in the first half of the twentieth century.

After enjoying a golden age for more than 50 years, the reed organ’s popularity started to decline. Radio, television, and music recordings, which seldom used the reed organ, became the new way of becoming familiar with music. "Shoka" was soon considered out-of-date. Economical development created the market for both pianos and electronic organs, produced by the same manufactures who made the reed organs. Since Japanese homes were usually small in size, the reed organ was taken out to make way for the piano, which did become the new status symbol. Reed organs soon disappeared from the schools as well. Yamaha, the last manufacture of this instrument in Japan, stopped production in 2001.

The United States

The Centennial Organ

In 1876, America celebrated the first Centennial of the Declaration of Independence on July 4. To celebrate this momentous occasion, a grand international fair called the Centennial Exposition, was held at Fairmount Park, Philadelphia. Americans were able to display their new industrial might and technological achievements. Ten million visitors saw the telephone, typewriter, air brake, reaper, and internal combustion engine for the first time. Included in this exhibition was the highly popular American reed organ.

A part of this technological expansion was the Prince firm, which already had been in existence for 30 years. George A. Prince & Co. of Buffalo exhibited its latest model, the "New Centennial Style Organ," conceived and designed especially for introduction to the nation at the Centennial Exposition.

The Centennial Organ weighed a hefty 365 pounds and featured "eleven stops, with Ivory Plates and Ivory Fronts to Keys," including "full organ knee stop and orchestra swell." It was housed in a 5-foot-2-inch "elegant walnut case in extra oil finish," with ornaments tipped and striped in gold bronze, its overall design characterized by flat rectangular and triangular panels with marquetry, inlay, and shallow carving.

Claiming that the new organ was "vastly superior to any reed organ ever made," the catalog said the instrument "permitted close imitation of an entire orchestra. Sounds that could be simulated were of the clarinet, flute, saxophone, cornet, violin, bassoon, violoncello, etc., either singly in solo or in ensemble to produce the 'orchestra' effect."

In retrospect, Prince had introduced the larger reed organ that became popular not only in the United States, but also swept Europe and Japan until the first World War. Many factories sprang up all over the United States, Europe and Japan, making large suction type reed organs. Two major companies in the United States, Estey and Mason & Hamlin, also became dominant players in the field.

Canada

The American organ was built in Canada as early as 1865, by R.S. Williams and soon afterwards by W. Bell, D.W. Karn, and many other companies. It had enlarged, vertical bellows and was encased in a solid desk-style cabinet with drawstops over the keyboard. Until the 1870s, it remained fairly simple in design and was less than four feet in height.

By the late 1870s, however, demand had grown and competition among manufacturers was increasingly sharp. In Ontario, companies such as Dominion (Bowmanville), Doherty (Clinton), and Thomas (Woodstock) entered into the production and assembling of reed organs. As a result, factories grew in size and number, though many were merely parts and assembly shops. While most were located in Ontario and in southern Quebec, a few could be found in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia and in Victoria, British Columbia.

Equipment became more sophisticated and later instruments were built with more complex actions and elaborate case designs. Gradually the methods of voicing the reeds became less individual. Many such instruments resembled High Victorian furniture rather than organ consoles.

Less expensive, lighter, and requiring less maintenance than pianos, reed organs were at their most popular in the years 1870-1910, and public demand was increased by highly exaggerated newspaper advertisements. Most models were intended for home use, though some were found in auditoriums. As early as the 1870s, larger companies manufactured some two-manual models for church and orchestra use. In most instances these lacked foot pedals and required two operators - a player and someone to pump the handle located on one side of the instrument. Like single-manual reed organs, these had less individuality of sound than pianos or pipe organs.

During the height of their popularity, thousands of reed organs were produced each year. Several manufacturers also built pianos and in this period reed organs and pianos often looked very much alike. Some of the larger companies established factories and agencies in England and Australia. The advent of other forms of music-making and entertainment (the player piano after 1901 and, later, the gramophone and radio) led to a decline in popularity, and by the 1930s even the larger builders had sold their businesses or switched to dealing exclusively in pianos and/or gramophones. Only Sherlock-Manning continued to build Doherty reed organs until the 1950s.

Fortunately, many individual instruments have survived and may be found in private homes and in museums such as Black Creek Pioneer Village, Toronto; the Brome County Historical Society, Knowlton, Quebec; the Bruce County Historical Museum, Southampton, Ontario; the Fort Malden National Historic Park Museum, Amherstburg, Ontario; the Ontario Pioneer Community Foundation, Kitchener, Ontario; the Organery, a collection assembled by Jan van der Leest of Truro, NS; the Trent River Museum, Trent River, Ontario; the Western Development museums in Yorkton and Saskatoon, Saskatchewan; and the Glenbow-Alberta Institute, Calgary.

Among experts on reed organs in Canada in the 1980s, were William L. Keizer of Ottawa, Tim Classey of Toronto, and Jan van der Leest of Truro, NS.

The United Kingdom

A flourishing industry of reed organ builders which were very similar to the above Canadian builders, sprang up in the United Kingdom, and were exported to other commomwealth nations.

Reed Organ Builders in Canada and the United Kingdom

Acadia Organ Co, Bridgetown, NS, fl 1878-82

C.W. & F.M. Andrus (Andrews?), Picton, Ont, fl 1857

Andrus Bros, London, Ont, ca 1859-74

Annapolis Organs, Annapolis, NS, fl 1880

John Bagnall &Co, Victoria, BC, 1863-85 (harmoniums by 1882)

Bell Organ and Piano Co (name changes), Guelph, Ont, 1864-1928

Daniel Bell Organ Co, Toronto, 1881-6

Berlin Organ Co, Berlin (Kitchener), Ont, fl 1880

G. Blatchford Organ Co, Galt, Ont, fl 1895; Elora, Ont, fl 1896

Abner Brown, Montreal, fl 1848-74

Canada Organ Co, London, Ont, ca 1865-?

Canada Organ Co, Toronto, 1875

Chute, Hall & Co, Yarmouth, NS, 1883-94

Compensating Pipe Organ Co, Toronto, fl 1900-10

Cornwall, Huntingdon, Que, before 1889-95 (see Pratte)

Cowley (or Conley?) Church Organ Co, Madoc, Ont, fl 1890

Dales & Dalton, Newmarket, Ont, fl 1870

R.H. Dalton, Toronto, 1869-82?

Darley and Robinson (see Dominion Organ and Piano Co)

W. Doherty & Co, Clinton, Ont, 1875-1920 (later owned by Sherlock-Manning Co)

Dominion Organ and Piano Co, Bowmanville, Ont, 1873-ca 1935

Eben-Ezer Organ Co, Clifford, Ont, 1935

Gates Organ and Piano Co, ca 1872-82 Malvern Square, NS; 1882-after 1885 Truro, NS

Goderich Organ Co, Goderich, Ont, fl 1890-1910

A.S. Hardy & Co, Guelph, Ont, fl 1874

John Jackson and Co, Guelph, Ont, fl 1872-3, 1880-3?

D.W. Karn Co, Woodstock, Ont, ca 1867-1924

J. & R. Kilgour, Hamilton, Ont, ca 1872-88 as dealers, 1888-99 as piano and organ company

McLeod, Wood & Co, Guelph, Ont, fl 1869-72; later R. McLeod & Co, London, Ont, fl 1874-5

Malhoit & Co, Simcoe, Ont, fl 1875

Charles Mee, Kingston, Ont, fl 1870

John M. Miller (later Miller & Karn and D.W. Karn), Woodstock, Ont, fl 1867

Mudge & Yarwood Manufacturing Co, Whitby, Ont, 1873-?

New Dominion Organ Co, Saint John, NB, fl 1875

William Norris, North York, Ont, fl 1867

Ontario Organ Co, Toronto, 1884

Oshawa Organ and Melodeon Manufacturing Co, 1871-3 (see Dominion Organ and Piano Co)

Pratte, Montreal, 1889-1926 (harmoniums built ca 1912)

Rappe & Co, Kingston, Ont, ca 1871-ca 1887

J. Reyner, Kingston, Ont, ca 1871-ca 1885

Sherlock-Manning Organ Co, London, Ont, later Clinton, Ont, 1902-78 (reed organs built 1902-1950s)

J. Slown, Owen Sound, Ont, fl 1871-89

David W. & Cornelius D. Smith, Brome, Que, 1875-?

Smith & Scribner, Chatham, Ont, fl 1864-5

Frank Stevenson, North York, Ont, fl 1867

Edward G. Thomas Organ Co, Woodstock, Ont, 1875-?

James Thornton & Co, Hamilton, Ont, fl 1871-89

Toronto Organ Co, Toronto, 1880

William Townsend, Toronto, fl late 1840s, Hamilton 1853-5

Uxbridge Organ Co, Uxbridge, Ont, fl 1872-1909

S.R. Warren and Son, Toronto, fl 1878-ca 1910

Elijah West, West Farnham, Que, fl 1860-75

Thomas W. White & Co, Hamilton, Ont, 1863-after 1869

R.S. Williams &Sons, Toronto, ca1854-ca 1952 (reed organs built in 19th century only)

Wilson & Co, Sherbrooke, Que

Wood, Powell & Co, Guelph, Ont, fl 1883-4

Woodstock Organ Factory, Woodstock, Ont, fl 1876 (see D.W. Karn)

Author Tim Classey, Helmut Kallmann

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ahrens, Christian. Das Harmonium. Frankfurt: E. Bochinsky, 1996. ISBN 3-923-63905-8.

- Ahrens, Christian, and Jonas Braasch. Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein: de uitvinder van de orgelregisters met doorslaande tongen. München: Katzbichler, 2003. ISBN 3-873-97582-3.

- Gellermann, R.F. The American Reed Organ and the Harmonium. 1997.

- Gellermann, R.F. The International Reed Organ Atlas. 1998.

External links

All links retrieved December 7, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 23:40:30 | 81 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Reed_Organ | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF