Seal

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

From Jewish Encyclopedia (1906) Seal:

By: Joseph Jacobs , Albert Wolf

An instrument or device used for making an impression upon wax or some other tenacious substance. At a very early period the Jews, like the other peoples of western Asia, used signets which were cut in intaglio on cylindrical, spherical, or hemispherical stones, and which were employed both to attest documents (Neh. x. 1

et seq.

) instead of a signature, and as seals (Isa. xxix. 11). They were highly valued and carefully guarded (Hag. ii. 23) as tokens of personal liberty and independence, while as ornaments they were suspended by a cord on the breast (Gen. xxxviii. 18), and subsequently were worn on a finger of the right hand (Jer. xxii. 24) or on the arm (Cant. viii. 6). A large number of ancient Hebrew seals has been preserved, although it is difficult to distinguish them from Aramaic and Phenician signets, both on account of the similarity of the script and because of the figures; these frequently contain symbols connected with idolatry, especially in the case of the oldest specimens, which date probably from the eighth century

, and

, and

, which frequently occur on seals, indicate that they are not Aramaic, and although the grammatical form of the name also helps to indicate the origin, it is the script which is usually the decisive factor; for the Aramaic, Phenician, and ancient Hebrew alphabets, derived indeed from the same source, each developed in the course of time according to an individual type, although this is a surer criterion in the later seals than in the earlier ones. The inscriptions on the seals usually give the name of the owner, with the occasional addition of the name of the father or husband, although other phrases sometimes occur, such as "May

, which frequently occur on seals, indicate that they are not Aramaic, and although the grammatical form of the name also helps to indicate the origin, it is the script which is usually the decisive factor; for the Aramaic, Phenician, and ancient Hebrew alphabets, derived indeed from the same source, each developed in the course of time according to an individual type, although this is a surer criterion in the later seals than in the earlier ones. The inscriptions on the seals usually give the name of the owner, with the occasional addition of the name of the father or husband, although other phrases sometimes occur, such as "May

It is noteworthy that a number of the seals which have been preserved belonged to women, although in later times it was not customary for females to wear sealrings in Palestine (Shab. vi. 3;

ib.

Gem.), while in Europe, on the contrary, women have worn them since the Middle Ages (

see Ring

). In both the tannaitic and amoraic periods the hoop of the ring was occasionally made of sandalwood and the seal of metal, or vice versa (Shab. vi. 1;

ib.

Gem. 59b). Seals dipped in a sort of India ink were used for signing documents, or the impression was made in clay if the document was inscribed on a tablet (see also the factory-marks,

Seal-rings were worn generally in Babylon, according to Herodotus and Strabo; but since they were regarded as a mark of distinction, Mohammed's second successor, the calif Omar (581-644), forbade Jews and Christians to wear them, although he made an exception in favor of the exilarch Bostanai, who was thus enabled to give an official character to his documents and decrees (for his emblem see

[

[

; see illustration in

; see illustration in

. Both the figures on the Ratisbon seal appear also on the seal of Masip Crechent ("Jahrb. Gesch. der Jud." ii. 290), and on a Swiss seal of about the same period with an inscription no longer legible (Plate ii., Fig. 29).

. Both the figures on the Ratisbon seal appear also on the seal of Masip Crechent ("Jahrb. Gesch. der Jud." ii. 290), and on a Swiss seal of about the same period with an inscription no longer legible (Plate ii., Fig. 29).

Even individual Jews, like the nobility, as being freemen and servants of the Imperial Chamber, were entitled to have seals; this privilege, however, like many others, was sometimes recognized and sometimes denied, as is shown, to cite but one of many examples, by a passage in a receipt of the Magdeburg community dated 1493, "because none of them have seals" ("Monatsschrift," 1865, p. 366), although the Jews of that city had affixed a seal to a document in 1364 ("Cod. Dipl. Anhaltin." iv. 320). The conditions were similar in other European countries; thus in 1396 Duke William of Austria decreed that all promissory notes should be sealed both by the city judge and by the Jews judge (Nübeling, l.c. p. 205). Further, in a manuscript of the municipal archives of Presburg of the year 1376 is found the enactment with regard to the "Jüdenpüch," that "a Christian and a Jew shall seal the book with their seals" (Winter, "Jahrb." 5620, p. 16). In 1402 the chief rabbi ("rabbi mor") of Portugal, who was appointed by the king, and who had jurisdiction over all the Jews of the country, was ordered by John I. to have a signet, with the coat of arms of Portugal and the legend "Scello do Arraby [Arrabiado] Moor de Portugal," with which his secretary sealed all the responsa, decisions, and other documents which he issued; and the seven provincial chief justices appointed by him used a similar seal having the same coat of arms with the inscription "Seal of the ouvidor [the ouvidores] of the communities . . ." (Kayserling, "Gesch. der Juden in Portugal," pp. 10, 13).

Use in Spain.When Alfonso V. reorganized the legal affairs of the Jews in 1480, he decreed that the chief rabbi should act as judge in the name of the king, and should seal his verdicts with the royal seal (Depping, "Die Juden im Mittelalter," pp. 322 et seq. ). On the other hand, the fact that Gedaliah ibn Yaḥya refers in his "Shalshelet ha-Ḳabbalah" to the coat of arms of his ancestor Yaḥya ibn Ya'ish, the favorite of Alfonso Henriquez, seems to indicate that the Jews of Portugal used seals at a very early time. The Spanish Jews also had signets; and there are two in the British Museum which probably date from the fourteenth century: the signet of the community of Seville (Plate ii., Fig. 27) and one belonging to Todros ha-Levi, son of Samuel ha-Levi (Plate iii., Fig. 9).

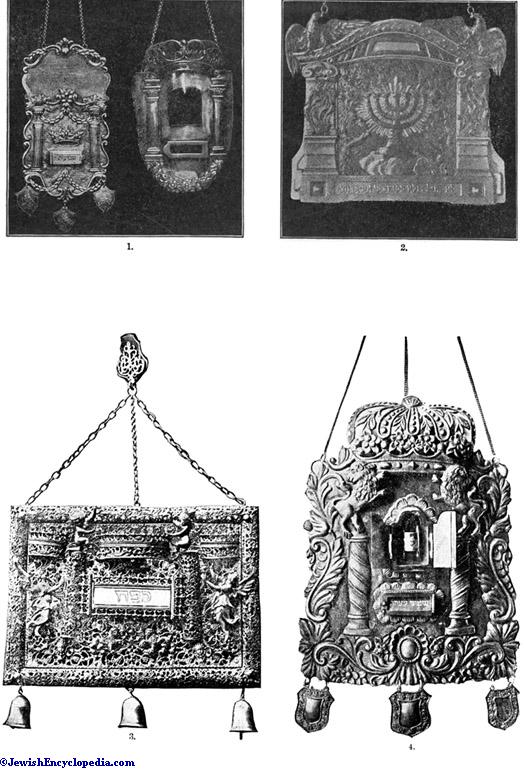

Double Seals.The Jews of Navarre, on the contrary, were obliged to have their documents sealed with the royal seal in the notary's office (which was farmed out), although they had their own courts in the thirteenth century (Kayserling, "Gesch. der Juden in Navarra," p. 73). The French king Philip II. decreed in 1206 that the Jews should affix to promissory notes a special seal, the signet to remain in the custody of two notables of the city (Depping, l.c. p. 148). His son, Louis VIII., however, deprived the Jews of this seal, perhaps because, as Depping assumes ( l.c. p. 155), it contained merely a Hebrew inscription without figures, in obedience to Jewish law, so that documents sealed with it escaped supervision, which led to many abuses. The plausibility of this hypothesis is increased by the fact that ultra-orthodox rabbis occasionally objected to seals with figures in intaglio (Löw, "Beiträge," i. 37, 57), even though such scruples were comparatively rare, and R. Israel Isserlein (15th cent.) unhesitatingly used a seal bearing a lion's head. Most Jewish seals of the Middle Ages had devices, together with an inscription in Latin or in the vernacular in addition to the Hebrew legend. Some Jews had a double seal, with a Hebrew inscription on one side and a legend in the vernacular on the other, the latter being used to sign legal papers in transactions with Christians; e.g. , the seal of Kalonymus (Plate ii., Figs. 24, 25). Such double seals were used also at a later time, as by Saul Wahl (Edelmann, "Gedullat Sha'ul," p. 22); and their employment continued even in the nineteenth century (Plate ii., Figs. 35, 36). While most medieval Jewish seals, as already noted, contain a figure in the center of the signet (Plate ii., Fig. 30), some seals occur in which the device is set in a scutcheon (Plate ii., Figs. 23, 24, 25, 26, 28, 29), an arrangement all the more remarkable since at that time it was the privilege of those "born to the shield and helmet." The shield in all these signets is French ("écu français"); but no occurrence of the helmet is known. Most of the seals were round (Plate ii., Fig. 30), though square seals also are found (Plate iii., Fig. 9), as well as seals in the form of a parabola (Plate ii., Fig. 34), the latter being used chiefly by the clergy.

"Armes Parlantes."Some of these seals are "armes parlantes," in which a device represents the owner's name, according to an etymology which may be either true or false, as in Vislin's seal (Plate ii., Fig. 26), which bears three fishes embowed in pairle, or in the seal of Masip Crechent, mentioned above, in which the crescent is a play upon the owner's name. Family seals ("armes de famille") were used by the medieval Jews, as is shown by the seal of Moses b. Menahem and his brothers Gumprecht and Visli ("Illustrirte Zeitung," July 2, 1881), which bears three Jew's hats with points meeting, in pairle (Plate ii., Fig. 23). The knightly family of Jüdden in Cologne, which was of Jewish descent, had a similar coat of arms: three Jew's hats argent in a field gules; crest, a bearded man (Jew) in a coat gules, wearing a Jew's hat argent (Fahne, "Gesch. der Kölner Geschlechter," p. 192).

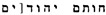

In later times new emblems appeared on the Jewish seals. Thus, the

Magen Dawid

("David's shield") is found with increasing frequency on communal seals even to the present time, occurring, for instance, on that granted to the ghetto of Prague by Emperor Ferdinand II. in 1627 (Plate i, Fig. 13), where it surrounds the Swedish hat and bears the legend "Sigillum Antiquæ Communitatis Pragensis Judæorum," with the letters

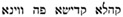

in the corners, which are to be read "magistrat." The shield of David is found also on the seal of the community of Vienna of the year 1655, with the inscription

in the corners, which are to be read "magistrat." The shield of David is found also on the seal of the community of Vienna of the year 1655, with the inscription

(Kaufmann, "Letzte Vertreibung," p. 151); on that of the community of Fürth, with the legend

(Kaufmann, "Letzte Vertreibung," p. 151); on that of the community of Fürth, with the legend

(Würfel, "Judengemeinde Fürth," p. 71); on that of Kremsir, about 1690 (Plate ii., Fig. 38); on that of the community of Kriegshaber, which bears the inscription

(Würfel, "Judengemeinde Fürth," p. 71); on that of Kremsir, about 1690 (Plate ii., Fig. 38); on that of the community of Kriegshaber, which bears the inscription

(Plate i., Fig. 18); on the seals of the Dresden and Beuthen communities (Plate ii., Figs. 33, 41), both of which date from the nineteenth century; and on many others.

(Plate i., Fig. 18); on the seals of the Dresden and Beuthen communities (Plate ii., Figs. 33, 41), both of which date from the nineteenth century; and on many others.

Different devices are found, moreover, on the seals of other communities. Thus, the seal used by the community of Halberstadt after its return to the city in 1661 bears a dove with an olive-branch hovering over the Ark, and the motto "Gute Hoffnung"in chief, with the words

below, and the legend "Vorsteher der Judenschaft in Halberstadt" (Plate i., Fig. 11). The seal of the community of Ofen has an Ark of the Law with the inscription

below, and the legend "Vorsteher der Judenschaft in Halberstadt" (Plate i., Fig. 11). The seal of the community of Ofen has an Ark of the Law with the inscription

and the words "Ofner Judengemeinde" (Plate i., Fig. 9). In 1817 seals were granted both to the principal community and to the Portuguese community of Amsterdam, the former bearing a lion holding in one paw a bundle of arrows and in the other a shield with a magen Dawid, and the latter having a shield with a pelican (see

and the words "Ofner Judengemeinde" (Plate i., Fig. 9). In 1817 seals were granted both to the principal community and to the Portuguese community of Amsterdam, the former bearing a lion holding in one paw a bundle of arrows and in the other a shield with a magen Dawid, and the latter having a shield with a pelican (see

and "Kamionker Gemein. Vorschtehr" (sic!) (Plate ii., Fig. 40), and the seal of the chief rabbinate of Swabia (seat of the rabbi of Pfersee), dating from the middle of the eighteenth century, which has simply the inscription

and "Kamionker Gemein. Vorschtehr" (sic!) (Plate ii., Fig. 40), and the seal of the chief rabbinate of Swabia (seat of the rabbi of Pfersee), dating from the middle of the eighteenth century, which has simply the inscription

(Plate i., Fig. 2).

(Plate i., Fig. 2).

Among Jewish corporations the butchers' gild of Prague is said by tradition to have received from King Ladislaus (12th cent.), in reward of bravery, a seal with the Bohemian lion, and it is known that in the seventeenth century this gild had a seal (Plate ii., Fig. 32) bearing on a shield engrailed a key with the magen Dawid, and in chief the Bohemian lion "queue fourchée," holding a butcher's ax in one paw, with the legend "Prager Jüdisch. Fleischer Zunfts Insigl." (sic!). The members of this gild bore also on their seals the same lion with the ax (Plate i., Fig., 5), while the members of the Jewish barbers' gild of the city likewise had the lion, with a bistoury. The Paris Sanhedrin had a seal with the imperial eagle holding the tables of the Law; and the Westphalian consistory was allowed to use a signet with the arms of the state and the legend "Königl. Westphael. Konsistorium der Israeliten." An official seal closely resembling that of the community was given in 1817 to the Hoofdcommissie tot de Zaken der Israelieten of Amsterdam. Four years previously the school board of the Philanthropin of Frankfort had received an official seal with the coat of arms of the grand duchy and the inscription "Schulrath der Israel. Gemeinde Frankfurt," while a beehive appears on the later seals of the institution.

Animal Designs.

Emblems indicating the name of the owner appear frequently on the seals of the Jews of the later period. These devices are either symbolic, as a bear for Issachar, or a bull's head for Joseph—

e.g.

, in the case of

Josel of Rosheim

—or are "armes parlantes," like the stag on the seal of Herz (Hirz = Hirsch) Wertheimer of Padua, the contemporary and adversary of Judah Minz (d. 1508), the rose-bush of the Rosalis family, the triple thorny branch of blossoms of

Spinoza

, and the crow with the severed shield and two hands of priests in chief in the seal of Abraham Menahem b. Jacob ha-Kohen Rabe of Porto (Rapoport). The two hands of priests as an emblem of the descendants of Aaron appear with great frequency on their seals after the end of the sixteenth century (Plate i., Fig. 4), and in like manner the water-jar is very common on the signets of Levites, as on that of Hirz Coma, described by Kaufmann ("Die Letzte Vertreibung der Juden aus Wien," Vienna, 1889). The lion, which appears chiefly on the seals of Portuguese Jews, perhaps represents on their signets the "lion of Judah," although elsewhere it frequently denotes merely the name "Judah," "Aryeh," or "Löw"; and a stone lion was carved on the house of the "hoher" R. Löw at Prague. The devices sometimes admitted of a mystic or cabalistic interpretation. Thus the two mountains on the seal of Solomon Molko (

c.

1501-31) alluded to the hills which he saw in his vision, and the two "lameds" below them, which were taken from his name, likewise had a mystic meaning (see letter in "'Emeḳ ha-Baka," p. 92a). Similarly, the serpent in a circle on the seal of Shabbethai Ẓebi was said to refer to his Messianic mission, since the Hebrew word for "serpent" (

) has the same numerical value as the word "Messiah" (

) has the same numerical value as the word "Messiah" (

).

).

Many of the devices that are represented on Jewish seals and whose meaning is no longer known may correspond to the emblems which the Jews in some places, as at Frankfort-on-the-Main and Worms (after 1641), were compelled to attach to their houses, such as a ship, a castle, a green hat, and which gave rise to such family names as "Rothschild" and "Grünhut." Among the emblems alluding to the occupation of the owner may be mentioned the anchor, referring to the merchant gild (Plate ii., Fig. 35), which occurs frequently on Jewish seals after the eighteenth century. Many Sephardic Jews of Jerusalem in official positions use seals representing the wailing-place (

); note,

e.g.

, the seal of the ab bet din Joseph Nissim (Bourla [?]; see

); note,

e.g.

, the seal of the ab bet din Joseph Nissim (Bourla [?]; see

.

.

The seals of other Jews had merely their owners' names (Plate i., Fig. 20), with occasionally the modest

(Plate i., Fig. 10; abbreviated

(Plate i., Fig. 10; abbreviated

, Plate i., Fig. 12) or

, Plate i., Fig. 12) or

(Plate i., Fig. 17). The father's name was generally affixed to that of the owner, and if his parent was still alive, the son added one of the pious formulas:

(Plate i., Fig. 17). The father's name was generally affixed to that of the owner, and if his parent was still alive, the son added one of the pious formulas:

(Plate i., Fig. 16),

(Plate i., Fig. 16),

(Plate ii., Fig. 31), or

(Plate ii., Fig. 31), or

(Plate i., Fig. 8). If the father was no longer living, the phrase

(Plate i., Fig. 8). If the father was no longer living, the phrase

was substituted (Plate i., Fig. 6). The owner of a seal sometimes styles himself

was substituted (Plate i., Fig. 6). The owner of a seal sometimes styles himself

(Plate i., Fig. 8). Other seals bear the initials of their owners, Moses Mendelssohn using a signet with only the letters

(Plate i., Fig. 8). Other seals bear the initials of their owners, Moses Mendelssohn using a signet with only the letters

(= Moses Dessau), and below the letters "M. M." At the present time the Jews of the leading nations generally use seals which differ in no respect from those of their fellow citizens of other creeds.

See Coat of Arms

.

(= Moses Dessau), and below the letters "M. M." At the present time the Jews of the leading nations generally use seals which differ in no respect from those of their fellow citizens of other creeds.

See Coat of Arms

.

- Seyler, Gesch. der Siegel, Leipsic, 1894;

- Levy, Siegel und Gemmen, Breslau, 1869;

- idem, Epigraphische Beiträge, in Jahrb. Gesch. der Jud. ii.;

- Löw, Graphische Requisiten und Erzeugnisse bei den Juden, Leipsic, 1870.

- On ancient Hebrew seals: Clermont-Ganneau, in Journal Asiatique, 1883, i. 123, 506; ii. 304; 1885, i. 321;

- Conder, Seal from Hebron, in Pal. Explor. Fund, Quarterly Statement, xxvii. 224.

- On medieval and modern seals: Anzeiger für Kunde der Deutschen Vorzeit, 1875, col. 106 (seals from Augsburg and southern France);

- Carmoly, in Revue Orientale, 1842, ii. 329 (Jewish seals of Metz);

- Gastaigne, Seeaux sur les Obligations Dues aux Juifs, in Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de la Charente, 1863, 53 pl.;

- Geiger's Jüd. Zeit. x. 281 et seq. (bilingual seals);

- Gross, in Monatsschrift, 1878, pp. 382, 472 et seq. (Historischer Jahresbericht, 1878 p. 46);

- Steinschneider, Hebr. Bibl. x. 86 et seq., xii. 92 (seal of Ueberlingen);

- Holtze, Das Strafverfahren Gegen die Märkischen Juden im Jahre 1510 (seals of Brunswick);

- King, Jewish Seal Found at Woodbridge, in Archeological Journal, 1884, xli. 168;

- idem, Norman Jewish Seal, ib. p. 242;

- Longpérier, Sceaux Juifs Bilingues du Moyen-Age, in Arch. Isr. xxxiii. 787;

- idem, Quelques Sceaux Juifs Bilingues, in Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 1872, p. 234;

- idem, Deux Sceaux Hébraïques au Moyen-Age, ib. 1873, p. 230;

- P. J[asse], Ein Siegel der Juden zu Augsburg vom Jahr 1298, in Orient, Lit. 1842, No. 5, col. 73;

-

R. E. J. iii. 148, iv. 278 et seq. (Swiss Jewish seals), v. 93 (Josel of Rosheim), vii. 125 (Jewish seals of Coblenz), xi. 82 (seal of Bordeaux), xi. 280 (Jewish seals of Pisck), xiv. 268 (Loeb, Un Sceaux Juif), xv. 122 et seq. (seals of Abraham b. Saadia and of

);

);

- Steinschneider, Cat. der Hebräischen Handschriften, No. 58, p. 38 (seal of Abraham Alfandari b. Elijah?), Berlin, 1878;

- Stern, in L. Geiger, Zeitschrift für die Gesch. der Juden, in Deutschland, i. 221 et seq., and bibliography;

- Stobbe, Die Juden in Deutschland, pp. 81, 87, 95 (note 106), 122;

- Sulzbach, in L. Geiger, l.c. (zodiacal seals);

- Ullrich, Sammlung Jüdischer Geschichten in der Schweiz, pp. 376, 433 (Swiss Jewish seals);

- Zeitschrift für die Gesch. des Oberrheins, xxxii. 430 (Ueberlingen seal).

Categories: [Jewish encyclopedia 1906]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 09/04/2022 17:16:17 | 73 views

☰ Source: https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/13365-seal.html | License: Public domain

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF