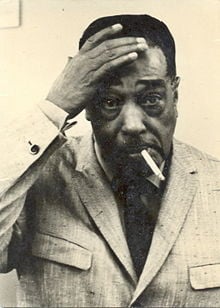

Duke Ellington

From Nwe

From Nwe

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was the foremost American jazz composer, pianist, and band leader. Some regard Duke Ellington as the most important figure to emerge from the U.S. jazz scene in the twentieth century. At the least, his stature can be compared to that of Louis Armstrong and Charlie Parker. In contrast to these two giants and other jazz greats, Ellington was not primarily a performer but a strong musical personality who expressed himself through his compositions and arrangements, and the performances of his band.

An impressive number of great soloists passed through the ranks of his orchestra, often remaining faithful for years, even decades. Many musical careers were almost entirely defined by their association with Ellington. His compositions were often written specifically for the style and skills of these individuals, such as "Jeep's Blues" for Johnny Hodges, "The Mooche" for Tricky Sam Nanton, and "Concerto for Cottie" for Cootie Williams. Ellington as a composer and arranger helped to elevate jazz from a popular music to a fully developed art form.

There were other jazz orchestras before Ellington’s—most notably Fletcher Henderson's—but Ellington's determination to find the right personnel and achieve the perfect synthesis between soloists and the orchestra set his music apart. Ellington was a consummate leader in extracting the best from his musicians, achieving a unity of purpose that was consistently greater than the sum of its parts. Not only through his musical leadership but through his natural dignity and probity, Ellington was able to transcend the limits imposed on black musicians who were typically seen as mere entertainers.

Ellington himself was reluctant to describe his work as anything more specific than "music." The word "jazz" was too narrow for Ellington, a man whose greatest compliment was to describe others who had impressed him as "beyond category." Indeed, throughout his career Ellington absorbed new influences and continually expanded the jazz vocabulary, anticipating later fusions between jazz and other musical genres.

Duke Ellington was among the twentieth century's best-known and respected African Americans whose artistic achievements brought recognition to African Americans in their struggle for full participation in America's cultural life. Ellington and his orchestra toured throughout the United States and Europe regularly before World War II and appeared in several films, and after the war continued to travel widely internationally.

Early life

Duke's father, James Edward Ellington, born in Lincolnton, North Carolina on April 15, 1879, was the son of a former slave. He moved to Washington, D.C. in 1886 with his family. Ellington was born to J.E. and Daisy Kennedy Ellington at 2129 Ward Place NW (the home of his maternal grandparents) in Washington. J.E. made blueprints for the United States Navy; he also worked as a White House butler for additional income. Daisy and J.E. were both piano players, and at the age of seven or eight Ellington began taking piano lessons from a Mrs. Clinkscales who lived at 1212 Street NW (the address erroneously, but commonly, given as his childhood home).

In his autobiography, Ellington claims he missed more lessons than he went to, feeling that the piano was not his talent. Over time, this would change. Ellington sneaked into Frank Holiday's Poolroom at fourteen and began to gain a greater respect for music. Hearing a mentor play the piano ignited Ellington's love for the instrument and he began to take his piano studies seriously.

He began performing professionally at the age of seventeen. Instead of going to an academic-oriented high school, he attended Armstrong Manual Training School to study commercial art. Three months before he was to graduate, he left school to pursue his interest in music. He never made broad claims for his piano playing, saying that many Washington piano teachers were better. His true instrument was the orchestra. Interestingly, his main rival, Count Basie, had exactly the same modest attitude towards his own piano playing, though both he and the Duke rank among the great stylists of jazz piano.

Early career

Duke Ellington began his artistic career as a sign painter in Washington, D.C., but by 1923 he had joined a small dance band known as The Washingtonians (which included drummer Sonny Greer), and moved to New York City. Shortly thereafter, the group became the house band of the Club Kentucky (often referred to as the "Kentucky Club"), an engagement which set the stage for the biggest opportunity in Ellington's life. In 1927, King Oliver turned down a job as the house band for Harlem's famed Cotton Club, and the offer fell into Ellington's lap. With a weekly radio broadcast and famous clientele pouring in nightly to see them, Ellington's popularity skyrocketed.

The 1930s band and its members

Ellington's band had become a large orchestra and the ranks had been filled by many men who would later become famous in their own right. Trumpeter Bubber Miley was the first major soloist, an early experimenter in jazz trumpet growling. Miley is credited with morphing the band's style from rigid dance instrumentation to a more "New Orleans" or earthy style. An alcoholic, Miley had to leave the band before they gained wider notoriety, and died in 1930 at the age of 28. He was replaced by trumpet great Cootie Williams who equally mastered the open trumpet and his own form of mute playing. Johnny Hodges joined the orchestra in 1928 and stayed until his death in 1970, except for two brief sabbaticals. Hodges became the band's undisputed superstar soloist, the king of romantic alto saxophone ballads with his swooning, creamy style remaining influential for years.

Barney Bigard, formerly a member of King Oliver's band, was a master of New Orleans jazz clarinet and stayed with the band for 12 years. His playing is showcased in "Mood Indigo." Harry Carney was the original innovator of the baritone saxophone and he remained that instrument’s classic representative, winning each Downbeat magazine poll until the arrival of Gerry Mulligan. Carney, who also pioneered circular breathing, was the longest lasting member of the orchestra, joining in 1927 and remaining with the group until his death in 1974 (just several months after Ellington's). Lawrence Brown brought a buttery, elegant trombone style that contrasted with that of Joe "Tricky Sam" Nanton. Nanton was the originator of a unique trombone style utilizing the plunger mute technique learned from Bubber Miley. Later in the decade, Juan Tizol’s valve trombone added a third voice for that instrument. His smooth, atmospheric playing had a Latin touch, as evidenced in the rendering of his famous composition "Caravan." Filling out the rhythm section were Ellington's childhood friend Sonny Greer, who stayed with the unit until 1950, and guitarist Fred Guy.

The Jungle sound

Like Fletcher Henderson, his only real rival during the late 1920s, Ellington quickly formed a personal style that distinguished his soon to become big band from the many commercially oriented dance orchestras of the time. During his tenure at the Cotton Club, Ellington developed the famous "jungle sound" that pervaded many of his recordings and compositions around 1930. Based on Miley’s and Nanton’s muted growl technique, the band produced a wild and hot sound and atmosphere that was intentionally reminiscent of the sound of a tropical jungle. Of course, theirs was a highly sophisticated city jungle, created for the exotic enjoyment of the club’s white audience.

However, for a creator of Ellington’s caliber, that sound was much more than a special effect. It became the primary carrier of a musical genius that entirely transcended its limitations. Ellington’s first signature song, "East St. Louis Toodle-Oo" (recorded in 1926 and several additional times in the following years) and his "Black and Tan Fantasy" and "Creole Love Call" (1927 and later) are perhaps the best examples of a style that was echoed in the playing of other bands, including Cab Calloway.

Ellington and the swing era

Ellington’s 1932 "It Don't Mean a Thing (If It Ain't Got That Swing)" remains symbolic of what came to be known the Swing Era and saw the rise to fame of Ellington’s band and several competing formations. However, despite the fact that Ellington could swing as much as anyone else, it has been remarked that he never fully joined the Swing Era. Unlike his main rival, Count Basie, who would be Swing’s quintessential representative along with Benny Goodman, Ellington’s strong musical personality always maintained some distance from the developments of the times. He used them, rather than fully identifying with them. From the beginning, his music had a complexity that put it somewhat at odds with the spirit of the entertainment industry. If he hadn’t been so enormously successful, Duke Ellington would thus have remained an outsider in jazz. Instead, he came to largely define it.

The 1930s saw Ellington's popularity continue to increase, greatly due to the wheeling and dealing of Duke's manager Irving Mills, who got more than his fair share of co-composer credits. While their United States audience remained mostly African-American in this period, a 1934 trip to Europe showed that the band had a huge following overseas. At home, meanwhile, Mills arranged a private train just for the band, so that they would not have to suffer the indignities of segregated accommodations while touring the South.

Ellington in the 1940s: the Blanton-Webster Band and beyond

The band reached a creative peak in the early 1940s, when Ellington wrote for an orchestra of distinctive voices and displayed tremendous creativity. Some of the musicians became a sensation of their own. The short-lived Jimmy Blanton transformed the use of the double bass in jazz, allowing it to function as a solo rather than a rhythm instrument alone. Several duo recordings with Ellington at the piano remain as a particular testimony to his ability as a soloist. Ben Webster, the Orchestra's first regular tenor saxophonist, started a rivalry with Johnny Hodges as the Orchestra's foremost voice in the sax section. Accordingly, specialists refer to the Ellington band of those short but essential years as the "Blanton-Webster band." Ray Nance joined in, replacing Cootie Williams who had "defected" to Benny Goodman. Nance added violin to the instrumental colors Ellington had at his disposal. A recording of Nance's first concert date, at Fargo, North Dakota, in November 1940, is probably the most effective display of the band at the peak of its powers during this period.

Three-minute masterpieces flowed from the minds of Ellington, Billy Strayhorn (Ellington’s alter ego from 1939 on), Duke's son Mercer Ellington, and members of the Orchestra. "Cottontail," "Mainstem," "Harlem Airshaft," "Streets of New York," "Caravan," "Perdido," and dozens of others date from this period.

Ellington the composer

Ellington's long-term aim became to extend the jazz form from the three-minute limit of the 78 rpm record side. He had composed and recorded the significantly longer "Creole Rhapsody" as early as 1931, but it was not until the 1940s that this became a regular feature of Ellington's work. In this, he was helped by Strayhorn, who had enjoyed a more thorough training in the forms associated with classical music than Ellington himself. The first of these, "Black, Brown, and Beige" (1943), was dedicated to telling the story of African-Americans, the place of slavery, and the church in their history. Unfortunately, starting a regular pattern, Ellington's longer works were not well received; "Jump for Joy," an earlier musical, closed after only six performances in 1941.

Another unique aspect of Duke Ellington as a jazz personality was that he could perhaps best be identified not as a performer or even as a band leader, but as a composer. During the classic period of jazz, composing generally stood in the shadow of performance and improvisation. Composing, supported by the art of arranging, was also largely limited to the production of themes or songs that often would do little more than serve as a pretext for further developments. There had nevertheless been great composers of wonderful melodies, such as Jelly Roll Morton, but Ellington gave the term composing a whole new meaning in jazz. He is the only jazz musician whose stature as a composer has been compared to that of classical composers. Only in much later times did other jazz composers with a similar musical ambition emerge.

Ellington’s uniqueness in that respect also underscores the frustrated efforts of other jazz greats who longed to produce works more ambitious than those allowed by the requirements of the entertainment industry. Their number includes James P. Johnson and Thomas Fats Waller, two great Harlem stride pianists whose style formed Ellington’s background.

The pianist

In spite of all the above, Ellington also occupies a special position in piano jazz. His style, while originating in the Harlem stride tradition, was highly personal. His favorite representative of stride piano was Willie "the Lion" Smith, whose playing had a unique poetic touch on top of his hot exuberance (Ellington composed "Portrait of the Lion" in his honor). Unlike Louis Armstrong, whose style essentially remained the same, Ellington became increasingly innovative, to such extent that he could be entirely comfortable with the most advanced musicians of the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1951, Ellington suffered a major loss of personnel, with Sonny Greer, Lawrence Brown, and most significantly, Johnny Hodges leaving to pursue other ventures.

Revival of his career

Ellington's appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival on July 7, 1956, was to return him to wider prominence. The feature "Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue," with saxophonist Paul Gonsalves's six-minute saxophone solo, had been in the band's book for a while, but on this occasion it nearly created a riot. The revived attention should not have surprised anyone—Hodges had returned to the fold the previous year, and Ellington's collaboration with Strayhorn had been renewed around the same time, under terms which the younger man could accept. Such Sweet Thunder (1957), based on Shakespeare's plays and characters, and The Queen's Suite the following year (dedicated to Queen Elizabeth II), were products of the renewed impetus which the Newport appearance had helped to create.

The late 1950s also saw Ella Fitzgerald record her Duke Ellington Songbook with Ellington and his orchestra, a clear recognition that Ellington's songs had now become part of the cultural canon known as the "Great American Songbook."

Ellington and modern jazz

Along with tenor player Coleman Hawkins, Ellington is one of only two major figures in jazz whose career not only spans over decades (from the 1920s to the 1970s), but who also remained constantly creative in an evolving style during that entire period. In some of his later recordings, side by side with contemporary musicians, Ellington proves his ability to remain himself while matching the creative evolution of the new times. His 1962 Money Jungle, recorded with Charles Mingus on bass and Max Roach on drums, is one of the best jazz albums ever recorded. Ellington also recorded with John Coltrane and Elvin Jones. His only recording with Hawkins, in 1962 as well, proves that he was also able to produce classic masterpieces at this late stage of his career.

Last years

Key musicians who had previously worked with Ellington returned to the Orchestra around 1960: Johnny Hodges in 1959, Lawrence Brown in 1960, and Cootie Williams two years later. Ellington was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize in 1965, but was turned down. His reaction: "Fate is being kind to me. Fate doesn't want me to be famous too young." In 1966, he performed his first "Sacred Concert," an attempt at fusing Christian liturgy with jazz, which was followed by two others. This caused enormous controversy in what was already a tumultuous time in the United States. Many saw the Sacred Music suites as an attempt to reinforce commercial support for organized religion, though the Duke simply said it was "the most important thing I've done," perhaps with a touch of hyperbole.

Though his later work is overshadowed by his music of the early 1940s, Ellington continued to make vital and innovative recordings, including The Far East Suite (1966), The New Orleans Suite (1970), and The Afro-Eurasian Eclipse (1971), until the end of his life. Increasingly, this period of music is being reassessed as people realize how creative Ellington was right up to the end of his life. He was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1969, and the Legion of Honor by France in 1973, the highest civilian honors in each country.

Duke Ellington died of lung cancer and pneumonia on May 24, 1974, and was interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery, The Bronx, New York City, next to other jazz celebrities.

Work in films

Ellington's film work began in 1929, starting with the short film Black and Tan. He also appeared in the film Check and Double Check. It was a major hit and helped introduce Ellington to a wide audience. He and his Orchestra continued to appear in films throughout the 1930s and 1940s, both in short films and in features such as Murder at the Vanities (1934). In the late 1950s, his work in films took the shape of scoring for soundtracks, notably Anatomy of a Murder (1959), with James Stewart, in which he also appeared fronting a roadhouse combo, and Paris Blues (1961), which featured Paul Newman and Sidney Poitier as jazz musicians.

A long-time fan of William Shakespeare, he wrote an original score for Timon of Athens that was first used in the Stratford Festival production that opened July 29, 1963, for director Michael Langham, who has used it for several subsequent productions, most recently in an adaptation by Stanley Silverman that expands on the score with some of Ellington's best-known works.

Posthumous dedications

A large memorial to Duke Ellington, created by sculptor Robert Graham, was dedicated in 1997 in New York's Central Park, near Fifth Avenue and 110th Street, an intersection named Duke Ellington Circle. In his birthplace of Washington, D.C., there stands a school dedicated to his honor and memory: the Duke Ellington School of the Arts. The school educates talented students, who are considering careers in the arts, by providing intensive arts instruction and strong academic programs that prepare students for post-secondary education and professional careers. The Duke Ellington Ballroom, located on the Northern Illinois University Campus, was dedicated in 1980. Although he made two more stage appearances before his death, what is considered Ellington's final "full" concert was performed there March 20, 1974.

The Ellington Orchestra itself continued intermittently as a "ghost band," led by Mercer Ellington (1919–1996), after his father's death.

A partial discography

- Okeh Ellington (1920s and 1930s) 2-CD set

- Duke: The Columbia Years (1927-1962) 3-CD set

- Early Ellington: The Complete Brunswick and Vocalion Recordings of Duke Ellington, 1926-1931. (Three CD Set) Decca GRD-3-640.

- Ellington Explosion, 1938-1941. Smithsonian Recordings R108. Live in Fargo, North Dakota, 1940.

- Beyond Category: The Musical Genius of Duke Ellington, compiled 1994 BMG Music and copyright 1994 Smithsonian Institution Press DMC2 / DMK2-1141

- Ellington at Newport-Complete (1999; expansion and restoration of the complete 1956 Newport Jazz Festival performance)

- Such Sweet Thunder (1957)

- Indigos (album)|Indigos (1957)

- Ella Fitzgerald Sings the Duke Ellington Songbook (1957)

- Newport Jazz Festival (1958)

- Festival Session (1959)

- Blues in Orbit (1959)

- Anatomy of a Murder (Soundtrack album) (1959)

- Duke Ellington and Johnny Hodges: Back to Back (1959)

- Duke Ellington and Johnny Hodges: Side by Side (1959)

- Piano in the Foreground (1961)

- Duke Ellington & John Coltrane (1962)

- Duke Ellington meets Coleman Hawkins (1962)

- Money Jungle (1962)

- The Great Paris Concert (1963, released 1973)

- Ella at Duke's Place (1965)

- The Symphonic Ellington (1965; 1985 reissue)

- Ella and Duke at the Cote D'Azur (1966)

- The Far East Suite (1966)

- And His Mother Called Him Bill (1967)

- Francis A. & Edward K. (1968)

- Latin American Suite (1968)

- 70th Birthday Concert (1969)

- New Orleans Suite (1970)

- The Afro-Eurasian Eclipse (1971)

- Live at the Whitney (1972, issued 1995)

- Duke Ellington's Incidental Music for Shakespeare's Play Timon of Athens adapted by Stanley Silverman (1993). Ellington does not perform on this recording, but it includes previously unreleased compositions.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dance, Stanley. The World of Duke Ellington. New York: Scribner's, 1970. Reprint, New York: Da Capo, 1981. ISBN 0306810158

- Ellington, Duke. Music is My Mistress. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1973. Reprint, New York: Da Capo, 1976. ISBN 0306800330

- Ellington, Mercer, with Stanley Dance. Duke Ellington in Person: An Intimate Memoir. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1978. Reprint, New York: Da Capo, 1978. ISBN 0306801043

- Hajdu, David. Lush Life: A Biography of Billy Strayhorn. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1996. ISBN 0865475121

- Hasse, John Edward. Beyond Category: The Life and Genius of Duke Ellington. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993. ISBN 0306806142

- Tucker, Mark, ed. The Duke Ellington Reader. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 0195093917

- Yanow, Scott. Duke Ellington. New York: Friedman/Fairfax Diane Pub, 1999. ISBN 0756781280

External links

All links retrieved October 6, 2017.

- Ellington on the Web. Retrieved May 24, 2007.

- A Duke Ellington Panorama including detailed discography.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/03/2023 21:26:35 | 30 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Duke_Ellington | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF