Spiro Agnew

From Nwe

From Nwe

| Spiro Theodore Agnew | |

|

|

|

39th Vice President of the United States

|

|

| In office January 20, 1969 – October 10, 1973 |

|

| President | Richard Nixon |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Hubert Humphrey |

| Succeeded by | Gerald Ford |

|

55th Governor of Maryland

|

|

| In office January 25, 1967 – January 7, 1969 |

|

| Lieutenant(s) | Marvin Mandel |

| Preceded by | J. Millard Tawes |

| Succeeded by | Marvin Mandel |

|

3rd Baltimore County Executive

|

|

| In office 1962 – 1966 |

|

| Preceded by | Christian H. Kahl |

| Succeeded by | Dale Anderson |

|

|

|

| Born | November 9 1918 Towson, Maryland |

| Died | September 17 1996 (aged 77) Berlin, Maryland |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Judy Agnew |

| Religion | Episcopalian |

Spiro Theodore Agnew (November 9, 1918 – September 17, 1996) was the thirty-ninth Vice President of the United States serving under President Richard M. Nixon, and the fifty-fifth Governor of Maryland. He is most famous for his resignation in 1973, after he was charged with the crime of tax evasion. He is also noted for his quick rise in politics: In six years from County Executive to Vice President. His successor as Vice-President, Gerald Ford, became President following Nixon's resignation as the first non-elected head of state in the history of the United States. An ardent opponent of communism and a strong supporter of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, Agnew's meteoric rise to political prominence was followed by as rapid a descent into obscurity.

Early life

Spiro Agnew was born Spiros Anagnostopoulos in the Towson section of Baltimore County, Maryland, to Theodore Spiros Anagnostopoulos and Margaret Akers, a native of Virginia. Spiro's father emigrated from Gargalianoi, Greece, to the United States in 1897, and owned a diner famous for its chicken souvlaki and spanakopita. He became a Baltimore Democratic ward leader and was well known in the local Greek community. He was Theodore Agnew's only child. His mother, Margaret, had two children from an earlier marriage that had left her a widow.

Agnew attended Forest Park High School in Baltimore before enrolling in Johns Hopkins University in 1937. He studied chemistry at Johns Hopkins University for three years before joining the U.S. Army and serving in Europe during World War II. He was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for his service in France and Germany.

Before leaving for Europe, Agnew worked at an insurance company, where he met Elinor Judefind, known as Judy. Agnew married Judy on May 27, 1942. They eventually had four children: Pamela, James Rand, Susan, and Kimberly.

Upon his return from the war, Agnew transferred to the evening program at the University of Baltimore School of Law. He studied law at night while working as a grocer and as an insurance salesman. In 1947, Agnew received his LL.B. (later amended to Juris Doctor) and moved to the suburbs to begin practicing law. He passed the bar in 1949.

Early political career

Agnew, raised a Democrat, switched parties and became a Republican. During the 1950s, he aided U.S. Congressman James Devereux in four successive winning election bids, before entering politics himself, in 1957. His appointment to the Baltimore County Board of Appeals by Democratic Baltimore County Executive Michael J. Birmingham marked his entry into politics. In 1960, Agnew made his first elective run for office as a candidate for Judge of the Circuit Court, finishing last in a five person contest. The following year, the new Democratic Baltimore County Executive, Christian H. Kahl, dropped him from the Zoning Board. Agnew protested loudly, which gained him some name recognition.

In 1962, Agnew ran for election as Baltimore County Executive, seeking office in a predominantly United States Democratic county that had seen no Republican elected to that position in the twentieth century. Running as a reformer and Republican outsider, he took advantage of a bitter split in the Democratic Party and was elected. Agnew backed and signed an ordinance outlawing discrimination in some public accommodations, among the first laws of this kind in the United States.

Governor of Maryland

After choosing not to seek a second term as County Executive, Agnew ran for the position of Governor of Maryland in 1966. In this overwhelmingly Democratic state, he was elected after the Democratic nominee, George P. Mahoney, a Baltimore paving contractor and perennial candidate running on an anti-integration platform, narrowly won the Democratic gubernatorial primary out of a crowded slate of eight candidates. Many Democrats opposed to segregation then crossed party lines to give Agnew the governorship by 82,000 votes.

As governor, Agnew worked with the Democratic legislature to pass tax and judicial reforms, as well as tough anti-pollution laws. Projecting an image of racial moderation, Agnew signed the state's first open housing laws and succeeded in getting the repeal of an anti-miscegenation law. However, during the riots that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., Agnew angered many African-American leaders by lecturing them about their constituents in stating, "I call on you to publicly repudiate all black racists. This, so far, you have been unwilling to do."

Vice presidency

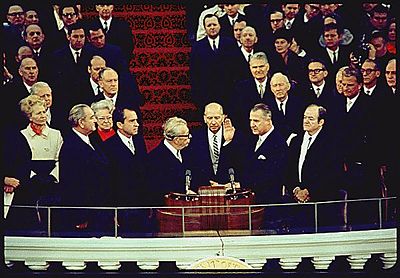

Agnew's moderate image, immigrant background and success in a traditionally Democratic state made him an attractive running mate for Nixon in 1968. In line with what would later be called Nixon's "Southern Strategy," Agnew was selected as a candidate for being sufficiently from the South to attract Southern moderate voters, yet not as identified with the Deep South, which could have turned off Northern centrists come election time. An ardent anti-communist, Agnew accused his democrat rival for the Vice-Presidency, Hubert Humphrfey, of being soft on communism.[1]

His vice presidency was the highest-ranking United States political office ever reached by a Greek-American citizen or, for that matter, a Marylander.

Agnew was a protege of Nelson Rockefeller, then governor of New York State and a head of the moderate wing of the Republican Party. Rockefeller was Nixon's chief opponent during the 1968 primary season. Some time before the 1968 GOP Convention, Rockefeller and Agnew had a falling out. Going into the 1968 GOP convention, neither Nixon nor Rockefeller had enough votes to clinch the nomination, but Nixon had nearly enough. As Nixon perused the possible vice presidential candidates and asked for input from his staff, Nixon thought of Agnew as someone that was a relative unknown on the national scene, a centrist in his views, not likely to upstage him and competent in domestic affairs. One of Nixon's staff invited Agnew to give the speech nominating Nixon at the 1968 convention. Agnew did so. Later in the proceedings Nixon offered him the vice presidential candidate on the ticket and Agnew accepted. Agnew's nomination was supported by many conservatives within the Republican Party and by Nixon. But a small band of delegates started shouting "Spiro Who?" and tried to place George W. Romney's name in nomination. Nixon's wishes prevailed and Agnew went from his first election as County Executive to Vice President in six years. One of the fastest rises in U.S. political history.

Agnew was known for his tough criticisms of political opponents, especially journalists and anti-Vietnam War activists. He was known for attacking his opponents with unusual, often alliterative epithets, some of which were coined by White House speech-writers William Safire and Pat Buchanan, including "nattering nabobs of negativism" (written by Safire), "pusillanimous pussyfoots," and "hopeless, hysterical hypochondriacs of history."

In short, Agnew was Nixon's "hatchet man" when defending the administration on the Vietnam War. Agnew was chosen to make several powerful speeches in which he spoke out against anti-war protesters and media portrayals of the Vietnam War, labeling them "Franco Un-American." Agnew toned down his rhetoric and dropped most of the alliterations after the 1972 election, with a view to running for president himself in 1976.

Alternative to Connally

By mid-1971, Nixon concluded that Spiro Agnew was not "broad-gaged" enough for the vice-presidency. He constructed a scenario by which Agnew would resign, enabling Nixon to appoint Treasury Secretary John Connally as vice president under the provisions of the Twenty-fifth Amendment.[2] By appealing to southern Democrats, Connally would help Nixon create a political realignment, perhaps even replacing the Republican party with a new party that could unite all conservatives. Nixon rejoiced at news that the vice president, feeling sorry for himself, had talked about resigning to accept a lucrative offer in the private sector. Yet while Nixon excelled in daring, unexpected moves, he encountered some major obstacles to implementing this scheme.

John Connally was a Democrat, and his selection might offend both parties in Congress, which under the Twenty-fifth Amendment had to ratify the appointment of a new vice president. Even more problematic, John Connally did not want to be vice president. He considered it a "useless" job and felt he could be more effective as a cabinet member. Nixon responded that the relationship between the president and vice president depended entirely on the personalities of whoever held those positions, and he promised Connally they would make it a more meaningful job than ever in its history, even to the point of being "an alternate President." But Connally declined, never dreaming that the post would have made him president when Nixon was later forced to resign during the Watergate scandal.

Nixon concluded that he would not only have to keep Agnew on the ticket but must publicly demonstrate his confidence in the vice president. He recalled that Eisenhower had tried to drop him in 1956, and believed the move had only made Ike look bad. Nixon viewed Agnew as a general liability, but backing him could mute criticism from "the extreme right." Attorney General John Mitchell, who was to head the reelection campaign, argued that Agnew had become "almost a folk hero" in the South and warned that party workers might see his removal as a breach of loyalty. As it turned out, Nixon won reelection in 1972, by a margin wide enough to make his vice presidential candidate irrelevant.

Immediately after his reelection, however, Nixon made it clear that Agnew should not become his eventual successor. The president had no desire to slip into lame duck status by allowing Agnew to seize attention as the frontrunner in the next election. "By any criteria he falls short," the president told John Ehrlichman: "Energy? He doesn't work hard; he likes to play golf. Leadership?" Nixon laughed. "Consistency? He's all over the place. He's not really a conservative, you know."

Nixon considered placing the vice president in charge of the American Revolution Bicentennial as a way of sidetracking him. But Agnew declined the post, arguing that the Bicentennial was "a loser." Because everyone would have a different idea about how to celebrate the Bicentennial, its director would have to disappoint too many people. "A potential presidential candidate," Agnew insisted, "doesn't want to make any enemies."

Resignation

After the 1972 landslide, Agnew was seen as Nixon's natural successor in the 1976 Presidential Election. With the strong support of the party's conservative wing, he had planned to decide on running only after the 1974 midterm elections. He had also hoped to build on his foreign policy credentials by visiting the Soviet Union. However, the scandal broke and damaged him. Nixon was also not supportive of Agnew replacing him, and in April 1973, his staff was cut back and duties trimmed.

On October 10, 1973, Spiro Agnew became the second Vice President to resign the office. Unlike John C. Calhoun, who resigned to take a seat in the United States Senate, Agnew resigned and then pleaded nolo contendere (no contest) to criminal charges of tax evasion and money laundering, part of a negotiated resolution to a scheme wherein he accepted $29,500 in bribes during his tenure as governor of Maryland. The bribes were paid to Agnew by some members of the construction industry to get their projects approved. When Agnew moved from Baltimore to Washington, DC, he continued to demand payments. Angered, the construction men turned government's witnesses. Agnew was fined $10,000 and put on three years' probation. The $10,000 fine only covered the taxes and interest due on what was "unreported income" from 1967. The plea bargain was later mocked as the "greatest deal since the Lord spared Isaac on the mountaintop" by former Maryland Attorney General Stephen Sachs. Students of Professor John Banzhaf from The George Washington University Law School, collectively known as Banzhaf's Bandits, found four residents of the state of Maryland willing to put their names on a case and sought to have Agnew repay the state $268,482—the amount he was known to have taken in bribes. After two appeals by Agnew, he finally resigned himself to the matter and a check for $268,482 was turned over to Maryland state Treasurer William James in early 1983. As a result of his nolo contendere plea, Agnew was later disbarred by the State of Maryland. Like most jurisdictions, Maryland lawyers are automatically disbarred after being convicted of a felony, and a nolo contendere plea exposes the defendant to the same penalties as a guilty plea.

His resignation triggered the first use of the Twenty-fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as the vacancy prompted the appointment and confirmation of Gerald Ford as his successor. It remains one of only two times that the amendment has been employed to fill a Vice Presidential vacancy. (The other time was when Ford, after becoming President, chose Nelson Rockefeller to succeed him as Vice President.)

As fate would have it, Nixon was forced from office. But Agnew's earlier resignation and criminal charges ruined any hopes of an Agnew presidency. The two men never spoke to each other again. As a gesture of reconciliation, Nixon's daughters invited Agnew to attend Nixon's funeral in 1994, and Agnew complied. In 1996, when Agnew died, Nixon's daughters returned the favor and attended Agnew's funeral.

Later life

Following his resignation, Agnew was found guilty of an income tax felony, fined $10,000 and sentenced to three years unsupervised probation. Maryland barred him from practicing law. Subsequently, he became an international trade executive with homes in Rancho Mirage, California; Arnold, Maryland; Bowie, Maryland; and Ocean City, Maryland. In 1976, he briefly re-entered the public spotlight and engendered controversy with anti-Zionism statements that called for the United States to withdraw its support for the state of Israel because of Israel's bad treatment of Christians, as well as what Gerald Ford publicly criticized as "unsavory" "remarks about Jews."[3]

In 1980, Agnew published a memoir in which he implied that Nixon and Alexander Haig had planned to assassinate him if he refused to resign the Vice-Presidency, and that Haig told him "to go quietly … or else."[4] Also in 1980, he considered, then decided against, running for Congress from Maryland. Agnew also wrote a novel, The Canfield Decision,[5] about a vice president who was "destroyed by his own ambition." Nixon reportedly made negative comments about Agnew. When John Erlichman, the President's counsel and assistant, asked him why he kept Agnew on the ticket in the 1972 election, Nixon replied that “No assassin in his right mind would kill me."

Legacy

Agnew may best be remembered for resigning from Nixon's administration and as Nixon's "hatchet man," especially in dealing with those who opposed the Vietnam War. Nixon's own subsequent resignation would have left Agnew as his successor to the Presidency. Instead, despite his meteoric rise to political prominence, he quickly slipped from the public mind.

Agnew died suddenly on September 17, 1996, at the age of 77 at Atlantic General Hospital, in Berlin, Maryland, in Worcester County (near his Ocean City home) only a few hours after being hospitalized and diagnosed with an advanced, yet to that point undetected, form of leukemia. He is buried at Dulaney Valley Memorial Gardens, a cemetery in Timonium, Maryland in Baltimore County. Most of his vice presidential papers and other papers are housed in the Hornbake Library, University of Maryland.

Notes

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, Agnew, Spiro T. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

- ↑ Biography List, The Conally Alternative. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ↑ New York Times, Agnew Asserts he is not a bigot. Retrieved September 20, 2007.

- ↑ Spiro T. Agnew, Go Quietly … or Else (New York: Morrow, 1980). ISBN 0-688-03668-6

- ↑ Spiro T. Agnew, The Canfield Decision (New York: Putnam Pub Group, 1976). ISBN 978-9997554871

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Agnew, Spiro T. Frankly Speaking; a Collection of Extraordinary Speeches. Washington: Public Affairs Press, 1969.

- Cohen, Richard M. and Jules Witcover. A Heartbeat Away; The Investigation and Resignation of Vice President Spiro T. Agnew. New York: Viking Press, 1974. ISBN 9780670364732

- Witcover, Jules. Very Strange Bedfellows: The Short and Unhappy Marriage of Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew. New York: PublicAffairs, 2007. ISBN 978-1-58648-470-5

External links

All links retrieved December 30, 2019.

| Preceded by: Christian H. Kahl |

Baltimore County Executive 1962–1966 |

Succeeded by: Dale Anderson |

| Preceded by: J. Millard Tawes |

Governor of Maryland 1967–1969 |

Succeeded by: Marvin Mandel |

| Preceded by: William E. Miller |

United States Republican Party Vice President of the United States :Category:Republican Party (United States) vice presidential nominees U.S. presidential election, 1968 (won), U.S. presidential election, 1972 (won) |

Succeeded by: Bob Dole |

| Preceded by: Hubert Humphrey |

Vice President of the United States January 20, 1969 to October 10, 1973 |

Succeeded by: Gerald Ford |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 06:00:56 | 45 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Spiro_T._Agnew | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF