Rembrandt

From Nwe

From Nwe | Rembrandt van Rijn | |

Portrait of Jan Six, 1654. Oil on canvas. |

|

| Birth name | Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn |

| Born | July 15, 1606 Leiden, Netherlands |

| Died | October 4, 1669 Amsterdam, Netherlands |

| Nationality | Dutch |

| Field | Painting, Printmaking |

| Famous works | See below |

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn (July 15, 1606 – October 4, 1669) is generally considered one of the greatest painters and printmakers in European art history and the most important in Dutch history. His contributions to art came in a period that historians call the Dutch Golden Age (roughly coinciding with the seventeenth century), in which Dutch world power, political influence, science, commerce, and culture—particularly painting—reached their pinnacle.

"No artist ever combined more delicate skill with more energy and power," states Chambers' Biographical Dictionary. "His treatment of mankind is full of human sympathy" (J.O. Thorne: 1962).

Life

Rembrandt van Rijn was born on July 15, 1606 (traditionally) but more probably in 1607 in Leiden, the Netherlands. Conflicting sources state that his family had either 7, 9, or 10 children. The family was well off. His father was a miller, and his mother was the daughter of a baker. As a boy he attended Latin school and was enrolled at the University of Leiden, although he had a greater inclination towards painting. He was soon apprenticed to a Leiden history painter, Jacob van Swanenburgh. After a brief but important apprenticeship with the famous painter Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam, Rembrandt opened a studio in Leiden, which he shared with friend and colleague Jan Lievens. In 1627, Rembrandt began to accept students, among them Gerrit Dou.

In 1629 Rembrandt was discovered by the statesman and poet Constantijn Huygens, who procured for Rembrandt important commissions from the court of the Hague. As a result of this connection, Prince Frederik Hendrik continued to purchase paintings from Rembrandt until 1646.

By 1631, Rembrandt had established such a good reputation that he received several assignments for portraits from Amsterdam. As a result, he moved to that city and into the house of an art dealer, Hendrick van Uylenburgh. This move eventually led, in 1634, to the marriage of Rembrandt and Hendrick's cousin, Saskia van Uylenburg. Saskia came from a good family. Her father had been a lawyer and burgemeester [mayor] of Leeuwarden. They were married in the local church, but without the presence of any of his relatives.

In 1639, Rembrandt and Saskia moved to a prominent house in the Jewish quarter, which later became the Rembrandt House Museum. It was there that Rembrandt frequently sought his Jewish neighbors to model for his Old Testament scenes. [1] Although by then they were affluent, the couple suffered several personal setbacks: their son Rumbartus died two months after his birth in 1635, and their daughter Cornelia died at just 3 weeks of age in 1638. Another daughter, also named Cornelia, also died in infancy. Only their fourth child, Titus, born in 1641, survived into adulthood. Saskia died in 1642 at the age of 30, soon after Titus's birth, probably from tuberculosis.

In the late 1640s, Rembrandt began a common-law relationship with his maid, Hendrickje Stoffels, who was 20 years his junior. In 1654 they had a daughter, whom they also named Cornelia, bringing Hendrickje an official reproach from the Reformed church for "living in sin." Rembrandt was not summoned to appear for the church council because he was not a member of the Reformed Church.

Rembrandt enjoyed financial success as an artist. He used a good deal of his wealth to buy many diverse and extravagant costumes and objects that inspired him and were often used in his paintings. He also purchased art pieces, prints (often used in his paintings), and rarities. The mismanagement of his money, as well as his liberal spending habits, most likely contributed to his eventual bankruptcy in 1656. As a result of the court judgment, he had to sell most of his paintings, his house, and his printing press, and move to a more modest accommodation on the Rozengracht. Here, Hendrickje and Titus started an art shop to make ends meet. In 1661 he was contracted to complete a series of major paintings for the newly built city hall, but only after the artist who had been previously commissioned died before completing the work.

Rembrandt outlived both Hendrickje and Titus. Rembrandt died soon after his son, on October 4, 1669 in Amsterdam, and was buried in an unmarked grave in Westerkerk.

Work

In a letter to a patron, Rembrandt offered the only surviving explanation of what he sought to achieve through his art: "the greatest and most natural movement." Whether this refers to objectives, material or otherwise, is open to interpretation; in any case, Rembrandt seamlessly melded the earthly and spiritual as has no other painter in Western art.[2]

Rembrandt produced over 600 paintings, nearly 400 etchings, and 2,000 drawings. He was a master of the self-portrait, producing almost a hundred of them throughout his long career, which includes more than 60 paintings and over 30 etchings and drawings. Together they give us a remarkably clear picture of the man, his appearance, and—more importantly—his deeper being, as revealed by his richly weathered face. While very little written documentation exists about him, his expressive self-portraits tell us quite a lot about the man and his inner life.

One of Rembrandt's most prominent techniques is his use of chiaroscuro, the theatrical employment of light and shadow.

He was heavily influenced by Caravaggio but finally mastered his own approach, using interplay between light and dark not merely as elements of composition and space, but to reveal the subtleties of character and depth of meaning.

Rembrandt's highly dramatic and lively presentation of subjects, devoid of the rigid formality that his contemporaries often displayed, and his deeply felt compassion for mankind irrespective of wealth and age proved to be a highly charged combination that brought him prominence and notoriety. He also showed a great deal of experimentation and variety of technique, which added to his mystique.

His immediate family—his wife Saskia, his son Titus, and his common-law wife Hendrickje—were often used as models for his paintings, many of which had mythical, biblical, or historical themes.

Periods, themes, and styles

It was during Rembrandt's Leiden period (1625-1631) that Pieter Lastman's influence was most prominent. Paintings were rather small, but rich in details (for example, in costumes and jewelry). Themes were mostly religious and allegorical.

During his early years in Amsterdam (1632-1636), Rembrandt began to paint dramatic biblical and mythological scenes in high contrast and of large format. He also began accepting portrait commissions.

In the late 1630s, Rembrandt produced many paintings and etchings of landscapes. Often these highlighted natural drama, featuring uprooted trees and ominous skies. Rembrandt's landscapes were more often etched than painted. The dark forces of nature made way for quiet Dutch rural scenes.

From 1640 his work became less exuberant and more sober in tone, reflecting personal tragedy. Biblical scenes were now derived more often from the New Testament than the Old Testament, as had been the case before. Paintings became smaller again. One exception is the huge Night Watch, his largest work, as worldly and spirited as any previous painting. The painting was commissioned for the new hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the musketeer branch of the civic militia. Rembrandt departed from the convention for such group commissions, which dictated the stately and formal line-up of personalities. Instead he painted an action scene, showing the militia readying themselves to embark on a mission. His new approach caused controversy. The painting was later reduced in size and moved to Amsterdam town hall in 1715. The painting now hangs in the largest hall of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, where it occupies the entire rear wall.

In the 1650s, Rembrandt's style changed again. Paintings increased in size. Colors became richer, brush strokes more pronounced. With these changes, Rembrandt distanced himself from earlier work and current fashion, which increasingly inclined toward fine, detailed works. Over the years, biblical themes were still depicted often, but emphasis shifted from dramatic group scenes to intimate portrait-like figures. In his last years, Rembrandt painted his most deeply reflective self-portraits.

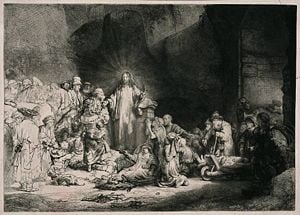

Rembrandt's etchings were enormously popular during his lifetime and today he is considered one of the finest masters of the medium. There are 79 of his original copper plates still in existence. Seventy-five of them were held in storage by a private collector for 18 years until they were finally revealed and put on public display in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1958. Rembrandt's print of "Christ Healing the Sick" was called the "Hundred Guilder Print" because of the handsome price it fetched by early collectors.

Rembrandt is renowned as much for his mastery of drawing as for painting. He used drawing not so much as studies for larger works, nor as finished presentations, but as notes, a way to capture his observations and reflections of everyday life, and his religious themes. About 1400 drawings survive, most of them unsigned. Perhaps an equal number have been lost.

Other Considerations

Restoration

During the century after Rembrandt's death, many of his paintings were covered over with layers of dark-toned varnish by dealers and collectors. This was done for several reasons. One was to preserve the surface of the painting. But another, more controversial reason, was to give Rembrandt's vivid and somewhat abrupt painting style a more unified look. Rembrandt was using bold strokes, impasto, and scumbles, which might have seemed disjointed from very close up. He had planned that the picture be viewed from a certain distance, which would provide the unifying by the viewer himself. Because of the dark 18th century varnishing, Rembrandt gained the undeserved reputation for painting in dark and sombre tones.

For example, the original title of the "Night Watch" was The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq. It was given the name "Night Watch" because it was so dimmed and defaced by dirt and varnish that it looked like a night scene. After it was cleaned, it was discovered to represent broad day—a party of musketeers stepping from a gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight.

Another instance of discovery took place when the painting Bellona was restored in 1947 by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. After the many layers of varnish was painstakingly removed, the vibrant colors were revealed, along with Rembrandt's signature and date, 1633, providing its authenticity.

Attributions

In 1968 the Rembrandt Research Project (RRP) was started under the sponsorship of the Netherlands Organization for the Advancement of Scientific Research (NWO). Art historians teamed up with experts from other fields to reassess the authenticity of works attributed to Rembrandt, using all methods available, including state-of-the-art technical diagnostics. The project also compiled a complete critical catalog of his paintings. As a result of their findings, many paintings that were previously attributed to Rembrandt have been taken from the list. Many of those are now thought to be the work of his students.

One example of activity is The Polish Rider, one of the treasures of New York's Frick Collection. Its authenticity had been questioned years before by several scholars, led by Julius Held. Many, including Dr. Josua Bruyn of the Foundation Rembrandt Research Project, attributed the painting to one of Rembrandt's closest and most talented pupils, Willem Drost, about whom little is known. The Frick Museum itself never changed its own attribution, the label still reading "Rembrandt" and not "attributed to" or "school of." More recent opinion has shifted in favor of the Frick, with Simon Schama in his 1999 book Rembrandt's Eyes, and a Rembrandt Project scholar, Ernst van de Wetering (Melbourne Symposium, 1997) both arguing for attribution to the master. Many scholars feel that the execution is uneven, and favor different attributions for different parts of the work.

Another painting, "Pilate Washing His Hands," is also of questionable attribution. Critical opinions of this picture have varied considerably since about 1905, when Wilhelm von Bode described it as "a somewhat abnormal work" by Rembrandt. However, most scholars since the 1940s have dated the painting to the 1660s and assigned it to an anonymous pupil.

The attribution and re-attribution work is ongoing. In 2005 four oil paintings previously attributed to Rembrandt's students were reclassified as the work of Rembrandt himself: Study of an Old Man in Profile and Study of an Old Man with a Beard from a U.S. private collection, Study of a Weeping Woman, owned by the Detroit Institute of Arts, and Portrait of an Elderly Woman in a White Bonnet, painted in 1640. [1]

Rembrandt's own studio practice is a major factor in the difficulty of attribution, since, like many masters before him, he encouraged his students to copy his paintings, sometimes finishing or retouching them to be sold as originals, and sometimes selling them as authorized copies. Additionally, his style proved easy enough for his most talented students to emulate. Further complicating matters is the uneven quality of some of Rembrandt's own work, and his frequent stylistic evolutions and experiments. It is highly likely that there will never be universal agreement as to what does and what does not constitute a genuine Rembrandt.

Signatures

"Rembrandt" is a modification of the spelling of the artist's first name, which he introduced in 1633. Roughly speaking, his earliest signatures (ca. 1625) consisted of an initial "R," or the monogram "RH" (for Rembrandt Harmenszoon), and starting in 1629, "RHL" (the "L" stood, presumably, for Leiden). In 1632 he added his patronymic to this monogram, "RHL-van Rijn," then began using his first name alone, "Rembrandt." In 1633 he added a "d," and maintained this form from then on.

Museum collections

- In the Netherlands, the most notable collection of Rembrandt's work is at Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum, including De Nachtwacht (The Night Watch) and De Joodse bruid (The Jewish Bride).

- Many of his self-portraits are held in The Hague's Mauritshuis.

- His home, preserved as the Rembrandt House Museum in Amsterdam, houses many examples of his etchings.

- Prominent collections in other countries can be found in Berlin, Kassel, St. Petersburg, New York City, Washington, DC, The Louvre and the National Gallery, London.

==A selection of works==250px|right|Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulip, 1632. Oil on canvas.]]

- 1629 An Artist in His Studio (The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts)

- 1630 The Raising of Lazarus (Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles)

- 1630-1635 A Turk (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1631 Portrait of Nicolaes Ruts (Frick Collection, New York)

- 1631 Philosopher in Meditation (Louvre, Paris, France)

- 1632 Jacob de Gheyn III (the most stolen painting in the world) (Dulwich Picture Gallery, London, England)

- 1632 Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulip (Mauritshuis, The Hague)

- 1632 Portrait of a Noble (Oriental) Man (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

- 1632 The Abduction of Europa (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

- 1633 Christ in the Storm on the Lake of Galilee (formerly at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston; stolen in 1990 and still at large)

- 1635 Belshazzar's Feast (National Gallery, London)

- 1635 Sacrifice of Isaac (State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg)

- 1636 The Blinding of Samson (Städel, Frankfurt am Main, Germany)

- 1636 Danaë (State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg)

- 1642 The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq better known as the Night Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

- ±1643 Christ Healing the Sick also known as The Hundred Guilders Print (Victoria and Albert Museum, London) etching, nicknamed for the huge sum (at that time) paid for it

- 1647 An Old Lady with a Book (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1648 Beggars Receiving Alms at the Door of a House (National Gallery of Art, Netherlands)

- 1650 The Philosopher (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1650 The Mill (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1653 Aristotle with a Bust of Homer (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

- 1654 Bathsheba at Her Bath (Louvre, Paris) (Hendrickje is thought to have modeled for this painting)

- 1655 Joseph Accused by Potiphar's Wife (National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.)

- 1655 A Man In Armour (Kelvingrove Museum & Art Gallery, Glasgow, Scotland)

- 1656 A Woman Holding a Pink (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1656 Jacob Blessing the Sons of Joseph (Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Kassel, Galerie Alte Meister, GK 249)

- 1657 The Apostle Paul (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1658 Selfportrait (Frick Collection, New York)

- 1658 Philemon and Baucis (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1659 Jacob Wrestling with the Angel

- 1659 Selfportrait (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

- 1660 Selfportrait (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

- 1660 Portrait of a Gentleman with a Tall Hat and Gloves (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1660 Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-Feather Fan (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1661 Conspiracy of Julius Civilis (Nationalmuseum, Stockholm) (Julius Civilis led a Dutch revolt against the Romans) (most of the cut up painting is lost, only the central part still exists)

- 1662 Syndics of the Drapers' Guild (Dutch De Staalmeesters) (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

- 1662 Portrait of a Man in a Tall Hat (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1662-1663 A Young Man Seated at a Table (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1664 Lucretia (The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

- 1664 The Jewish Bride (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam)

- 1666 Lucretia (The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis)

- 1669 Return of the Prodigal Son (State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg)

Gallery

Notes

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Adams, Laurie Schneider. Art Across Time Vol. II. New York: McGraw-Hill College, 1999.

- Clough, Shepard B. European History in a World Perspective. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company, 1976. ISBN 0669855553

- Hughes, Robert (2006), "The God of Realism," The New York Review of Books (Rea S. Hederman) 53 (6) Review

- Schama, Simon. Rembrandt's Eyes. Knopf, 2001. ISBN 9780375709814

- Schwartz, Gary D. ed., The Complete Etchings of Rembrandt: Reproduced in Original Size. Dover Publications, 1994. ISBN 978-0486281810

- Van de Wetering, Ernst, et al., A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings - Volume IV. The Hague: Martinus-Nijhoff Publ., 2005. ISBN 1402032803

- __________. Rembrandt: The Painter at Work. Amsterdam University Press, 2002. ISBN 9789053562390

- Wallace, Robert, et. al., The World of Rembrandt. Time-Life Books, 1968. ASIN B0007HCBB2

External links

All links retrieved December 7, 2022.

- Rembrandt's house in Amsterdam .

- Rembrandt Research Project.

- Webmuseum Paris.

- Self-portraits.

- Encyclopedia Britannica article.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 04:48:40 | 95 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Rembrandt_Harmenszoon_van_Rijn | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF