Cetacean

From Nwe

From Nwe | Cetaceans |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Humpback Whale breaching

|

||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||

Mysticeti |

Cetacea (L. cetus, whale) is an order of aquatic, largely marine mammals, including whales, dolphins and porpoises. Cetaceans have a nearly hairless, fusiform (spindle-shaped) body with anterior limbs in the form of flippers, and a flat, notched tail with horizontal flukes that lacks bony support. The tiny hindlimbs are vestigial; they do not attach to the backbone and are hidden within the body.

Of the four groups of marine mammals—pinnipeds (walruses, sea lions, eared seals, fur seals, and true seals), sirenians (manatees and dugongs), and sea otters are the others—the cetanceans are the most fully adapted to aquatic life. They have an exclusively aquatic life cycle from birth until death.

Cetaceans have been linked with humans for thousands of years, providing such benefits as food (for people and sled dogs), whale oil (for light and warmth), and tools from bones and baleen. Their grace, power, intelligence, and beauty appeal to people's internal nature, being featured attractions in boat tours, ocean parks, literature, and art. However, exploitation has also led to many species ending up on endangered lists.

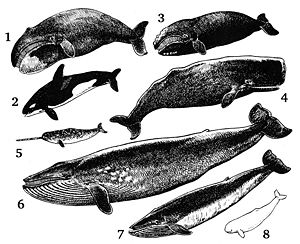

The order Cetacea contains about 90 species, all marine except for five species of freshwater dolphins. The order is divided into two suborders, Mysticeti (baleen whales) and Odontoceti (toothed whales, which includes dolphins and porpoises).

Cetaceans can be found in marine waters throughout the world, and several large freshwater systems in Latin America and Asia, including the Amazon River. They also appear in such partially enclosed areas as the Black Sea, Red Sea, Hudson Bay, the Arabian Gulf, and the Baltic Sea. They range in size from 1.5 meter, 120-pound dolphins and porpoises to the Blue Whale, the world's largest animal, and perhaps the largest animal ever to roam the earth, reaching 33 meters (100 feet) long and up to 200 tons (Gzimek 2004).

Cetus is Latin and is used in biological names to mean "whale"; its original meaning, "large sea animal," was more general. It comes from Greek ketos ("sea monster"). Cetology is the branch of marine science associated with the study of cetaceans. Linnaeus was the one who assigned the Cete to the order of mammals.

Cetaceans as mammals

Cetaceans are mammals. Mammals are the class (Mammalia) of vertebrate animals characterized by the presence of hair and mammary glands, which in females produce milk for the nourishment of young. As mammals, cetaceans have characteristics that are common to all mammals: They are warm-blooded, breathe in air utilizing lungs, bear their young alive and suckle them on their own milk, and have hair.

Whales, like mammals, also have a diaphragm, a muscle below the rib cage that aids breathing and it is a prehepatic diaphragm, meaning it is front of the liver. Mammals also are the only vertebrates with a single bone in the lower jaw.

Another way of discerning a cetacean from a fish is by the shape of the tail. The tail of a fish is vertical and moves from side to side when the fish swims. The tail of a cetacean has two divisions, called flukes, which are horizontally flattened and move up and down, as cetaceans' spines bend in the same manner as a human spine.

Whales have very limited hair in isolated areas, thus reducing drag in the water. Instead, they maintain internal temperatures with a thick layer of blubber (vascularized fat).

The flippers of cetaceans, as modified front limbs, show a full complement of arm and hand bones, albeit compressed in length (Grzimek 2004).

The range in body size is greater for the cetaceans than for any other mammalian order (Grzimek 2004).

Types of cetaceans

Cetaceans are divided into two major suborders: Mysticeti (baleen whales) and Odontoceti (toothed whales, including whales, dolphins, and porpoises).

- Mysticeti. The baleen whales (Mysticeti) are characterized by the baleen, a sieve-like structure in the upper jaw made of the tough, structural protein keratin. The baleen is used to filter plankton from the water. The mysticete skull has a bony, large, broad, and flat upper jaw, that is placed back under the eye region (Grzimek 2004). They are characterized by two blowholes. Baleen whales are the largest whales. The families of baleen whales include the Balaenopteridae (humpback whales, fin whales, Sei Whale, and others), the Balaenidae (right and bowhead whales), the Eschrichtiidae (gray whale), and the Neobalaenidae (pygmy right whales), among others. The Balaenopteridae family (rorquals) also includes the Blue Whale, the world's largest animal.

- Odontoceti. The toothed whales (Odontoceti) have teeth and prey on fish, squid, or both. This suborder includes dolphins and porpoises as well as whales. In contrast with the mysticete skull, the main bones of the odontocete upper jaw thrust upward and back over the eye sockets (Grzimek 2004). Toothed whales have only one blowhole. An outstanding ability of this group is to sense their surrounding environment through echolocation. In addition to numerous species of dolphins and porpoises, this suborder includes the Beluga whale and the sperm whale, which may be the largest toothed animal to ever inhabit Earth. Families of toothed whales include, among others, the Monodontidae (belugas, narwhals), Kogiidae (Pygmy and dwarf sperm whales), Physteridae (sperm whale), and Ziphidae (beaked whales).

The terms whale, dolphin, and porpoise are used inconsistently and often create confusion. Members of Mysticeti are all considered whales. However, distinguishing whales, dolphins, and porpoises among the Odontoceti is difficult. Body size is useful, but not a definitive distinction, with those cetaceans greater than 9ft (2.8m) generally called whales; however, some "whales" are not that large and some dolphins can grow larger (Grzimek 2004). Scientifically, the term porpoise should be reserved for members of the family Phocoenidae, but historically has been often applied in common venacular to any small cetacean (Grzimek 2004). There is no strict definition of the term dolphin (Grzimek 2004).

Respiration, vision, hearing and echolocation

Since the cetacean is a mammal, it needs air to breathe. Because of this, it needs to come to the water's surface to exhale its carbon dioxide and inhale a fresh supply of oxygen. As it dives, a muscular action closes the blowholes (nostrils), which remain closed until the cetacean next breaks the surface. When it does, the muscles open the blowholes and warm air is exhaled.

Cetaceans' blowholes are located on top of the head, allowing more time to expel stale air and inhale fresh air. When the stale air, warmed from the lungs, is exhaled, it condenses as it meets the cold air outside. As with a terrestrial mammal breathing out on a cold day, a small cloud of 'steam' appears. This is called the 'blow' or 'spout' and is different in terms of shape, angle, and height, for each cetacean species. Cetaceans can be identified at a distance, using this characteristic, by experienced whalers or whale-watchers.

The cetacean's eyes are set well back and to either side of its huge head. This means that cetaceans with pointed "beaks" (such as many but not all dolphins) have good binocular vision forward and downward, but others with blunt heads (such as the Sperm Whale) can see either side but not directly ahead or directly behind. Tear glands secrete greasy tears, which protect the eyes from the salt in the water. Cetaceans also have an almost spherical lens in their eyes, which is most efficient at focusing what little light there is in the deep waters. Cetaceans make up for their generally quite poor vision (with the exception of the dolphin) with excellent hearing.

As with the eyes, the cetacean's ears are also small. Life in the sea accounts for the cetacean's loss of its external ears, whose function is to collect airborne sound waves and focus them in order for them to become strong enough to hear well. However, water is a better conductor of sound than air, so the external ear was no longer needed: It is no more than a tiny hole in the skin, just behind the eye. The inner ear, however, has become so well developed that the cetacean can not only hear sounds tens of miles away, but it can also discern from which direction the sound comes.

Some cetaceans are capable of echolocation. Mysticeti have little need of echolocation, as they prey upon small fish that would be impractical to locate with echolocation. Many toothed whales emit clicks similar to those in echolocation, but it has not been demonstrated that they echolocate. Some members of Odontoceti, such as dolphins and porpoises, do perform echolocation. These cetaceans use sound in the same way as bats: They emit a sound (called a click), which then bounces off an object and returns to them. From this, cetaceans can discern the size, shape, surface characteristics, and movement of the object, as well as how far away it is. With this ability, cetaceans can search for, chase, and catch fast-swimming prey in total darkness. Echolocation is so advanced in most Odontoceti that they can distinguish between prey and non-prey (such as humans or boats). Captive cetaceans can be trained to distinguish between, for example, balls of different sizes or shapes.

Cetaceans also use sound to communicate, whether it be groans, moans, whistles, clicks, or the complex "singing" of the Humpback whale.

There is considerable variation in morphology among the various cetacean species. Some species lack a dorsal fin (such as right whales), others have only a hump or ridge (as the gray whale), and some have a prominent and tall dorsal fin (male killer whales and Spectacled porpoises) (Grzimek 2004).

Feeding

When it comes to food and feeding, cetaceans can be separated into two distinct groups. The "toothed whales" (Odontoceti), like sperm whales, beluga whales, dolphins, and porpoises, usually have lots of teeth that they use for catching fish, sharks, cephalopods (squids, cuttlefish, and octopuses), or other marine life. They do not chew their food, but swallow it whole. In the rare cases that they catch large prey, as when Orca (Orcinus orca) catch a seal, they tear "chunks" off it that in turn are swallowed whole. Killer whales are the only cetaceans known to feed on warm-blooded animals on a regular basis, consuming seals, sea otters, and other cetaceans (Grzimek 2004), as well as seabirds and sea turtles.

The "baleen whales" (Mysticeti) do not have teeth. Instead, they have plates made of keratin (the same substance as human fingernails), which hang down from the upper jaw. These plates act like a giant filter, straining small animals (such as krill and fish) from the seawater. Cetaceans included in this group include the Blue Whale, the Humpback Whale, the Bowhead Whale, and the Minke Whale.

Mysticeti are all filter feeders, but their strategies differ, with some swimming steadily with their mouth open and after a feeding run sweeping the food into the throat, while others are gulp feeders, taking in large volumes of water then closing the mouth and squeezing the water through the baleen. Not all Mysticeti feed on plankton: the larger whales tend to eat small shoaling fish, such as herrings and sardine, called micronecton. One species of Mysticeti, the gray whale (Eschrichtius robustus), is a benthic feeder, primarily eating sea floor crustaceans.

Evolution

Cetaceans are considered to have evolved from land mammals. They appear to be closely related to hoofed mammals (ungulates), such as cattle and horses. It is felt that they adapted to marine life about 50 million years ago, being derived from a hoofed carnivore that also gave rise to the artiodactyls, the even-toed ungulates, such as pigs and the hippopotamuses. Most paleotologiests considered them to have arisen from the Mesonychidae, an extinct family of primitive terrestrial amimals, and that this transition took place in the Tethys Sea (Grzimek 2004).

Artiodactyla, if it excludes the Cetacea, is a paraphyletic group. For this reason, the term Cetartiodactyla was coined to refer to the group containing both artiodactyls and whales (though the problem could just as easily be resolved by recognizing Cetacea as a subgroup of Artiodactyla.

The following is the proposed scenario. Over a period of a few million years during the Eocene period, the cetaceans returned to the sea, where there was a niche for large, surface-dwelling predators that had been empty since the demise of the mosasaurs and plesiosaurs. Because of the increase in available living space, there was no natural limit to the cetaceans' size (i.e. the amount of weight its legs could hold), since the water provided buoyancy. It had no longer any need for legs.

During this time, the cetacean lost the qualities that fitted it for land existence and gained new qualities for life at sea. Its forelimbs disappeared, and then its hind limbs; its body became more tapered and streamlined: a form that enabled it to move swiftly through the water. The cetacean's original tail was replaced by a pair of flukes that sculled with a vertical motion.

As part of this streamlining process, the bones in the cetaceans' front limbs fused together. In time, what had been the forelegs became a solid mass of bone, blubber, and tissue, making very effective flippers that balance the cetaceans' tremendous bulk.

To preserve body heat in cold oceanic waters, the cetacean developed blubber, a thick layer of fat between the skin and the flesh that also acts as an emergency source of energy. In some cetaceans the layer of blubber can be more than a foot thick. No longer needed for warmth, the cetacean's fur coat disappeared, further reducing the resistance of the giant body to the water.

The ear bone called the hammer (malleus) is fused to the walls of the bone cavity where the ear bones are, making hearing in air nearly impossible. Instead sound is transmitted through their jaws and skull bones.

Taxonomic listing

The classification here closely follows Rice (1998), Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution (1998), which has become the standard taxonomy reference in the field. There is very close agreement between this classification and that of Mammal Species of the World: 3rd Edition (Reed and Brownell 2005). Any differences are noted using the abbreviations "Rice" and "MSW3" respectively. Further differences due to recent discoveries are also noted.

Discussion of synonyms and subspecies are relegated to the relevant genus and species articles.

- ORDER CETACEA

- Suborder Mysticeti: Baleen whales

- Family Balaenidae: Right whales and Bowhead Whale

- Genus Balaena

- Bowhead Whale, Balaena mysticetus

- Genus Eubalaena

- Atlantic Northern Right Whale, Eubalaena glacialis

- Pacific Northern Right Whale, Eubalaena japonica

- Southern Right Whale, Eubalaena australis

- Genus Balaena

- Family Balaenopteridae: Rorquals

- Subfamily Balaenopterinae

- Genus Balaenoptera

- Common Minke Whale, Balaenoptera acutorostrata

- Antarctic Minke Whale, Balaenoptera bonaerensis

- Sei Whale, Balaenoptera borealis

- Bryde's Whale, Balaenoptera brydei

- Eden's Whale Balaenoptera edeni - Rice lists this as a separate species, MSW3 does not

- Omura's Whale, Balaenoptera omurai - MSW3 lists this is a synonym of Bryde's Whale but suggests this may be temporary.

- Blue Whale, Balaenoptera musculus

- Fin Whale, Balaenoptera physalus

- Genus Balaenoptera

- Subfamily Megapterinae

- Genus Megaptera

- Humpback Whale, Megaptera novaeangliae

- Genus Megaptera

- Subfamily Balaenopterinae

- † Genus Eobalaenoptera

- † Harrison's Whale, Eobalaenoptera harrisoni

- Family Eschrichtiidae

- Genus Eschrichtius

- Gray Whale, Eschrichtius robustus

- Genus Eschrichtius

- Family Neobalaenidae: Pygmy Right Whale

- Genus Caperea

- Pygmy Right Whale, Caperea marginata

- Genus Caperea

- Family Balaenidae: Right whales and Bowhead Whale

- Suborder Odontoceti: toothed whales

- Family Delphinidae: Dolphin

- Genus Cephalorhynchus

- Commerson's Dolphin, Cephalorhyncus commersonii

- Chilean Dolphin, Cephalorhyncus eutropia

- Heaviside's Dolphin, Cephalorhyncus heavisidii

- Hector's Dolphin, Cephalorhyncus hectori

- Genus Delphinus

- Long-beaked Common Dolphin, Delphinus capensis

- Short-beaked Common Dolphin, Delphinus delphis

- Arabian Common Dolphin, Delphinus tropicalis. Rice recognises this as a separate species. MSW3 does not.

- Genus Feresa

- Pygmy Killer Whale, Feresa attenuata

- Genus Globicephala

- Short-finned Pilot Whale, Globicephala macrorhyncus

- Long-finned Pilot Whale, Globicephala melas

- Genus Grampus

- Risso's Dolphin, Grampus griseus

- Genus Lagenodelphis

- Fraser's Dolphin, Lagenodelphis hosei

- Genus Lagenorhynchus

- Atlantic White-sided Dolphin, Lagenorhynchus acutus

- White-beaked Dolphin, Lagenorhynchus albirostris

- Peale's Dolphin, Lagenorhynchus australis

- Hourglass Dolphin, Lagenorhynchus cruciger

- Pacific White-sided Dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obliquidens

- Dusky Dolphin, Lagenorhynchus obscurus

- Tropical Dusky Dolphin, Lagenorhynchus spp.

- Genus Lissodelphis

- Northern Right Whale Dolphin, Lissodelphis borealis

- Southern Right Whale Dolphin, Lissodelphis peronii

- Genus Orcaella

- Irrawaddy Dolphin, Orcaella brevirostris

- Australian Snubfin Dolphin, Orcaella heinsohni. 2005 discovery, thus not recognized by Rice or MSW3 and subject to revision.

- Genus Orcinus

- Killer Whale, Orcinus orca

- Genus Peponocephala

- Melon-headed Whale, Peponocephala electra

- Genus Pseudorca

- False Killer Whale, Pseudorca crassidens

- Genus Sotalia

- Tucuxi, Sotalia fluviatilis

- Genus Sousa

- Pacific Humpback Dolphin, Sousa chinensis

- Indian Humpback Dolphin, Sousa plumbea

- Atlantic Humpback Dolphin, Sousa teuszii

- Genus Stenella

- Pantropical Spotted Dolphin, Stenella attenuata

- Clymene Dolphin, Stenella clymene

- Striped Dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba

- Atlantic Spotted Dolphin, Stenella frontalis

- Spinner Dolphin, Stenella longirostris

- Genus Steno

- Rough-toothed Dolphin, Steno bredanensis

- Genus Tursiops

- Indian Ocean Bottlenose Dolphin, Tursiops aduncus

- Common Bottlenose Dolphin, Tursiops truncatus

- Genus Cephalorhynchus

- Family Monodontidae

- Genus Delphinapterus

- Beluga, Delphinapterus leucas

- Genus Monodon

- Narwhal, Monodon monoceros

- Genus Delphinapterus

- Family Phocoenidae: Porpoises

- Genus Neophocaena

- Finless Porpoise, Neophocaena phocaenoides

- Genus Phocoena

- Spectacled Porpoise, Phocoena dioptrica

- Harbour Porpoise, Phocoena phocaena

- Vaquita, Phocoena sinus

- Burmeister's Porpoise, Phocoena spinipinnis

- Genus Phocoenoides

- Dall's Porpoise, Phocoenoides dalli

- Genus Neophocaena

- Family Physeteridae: Sperm Whale family

- Genus Physeter

- Sperm Whale, Physeter macrocephalus

- Genus Physeter

- Family Kogiidae - MSW3 treats Kogia as a member of Physeteridae

- Genus Kogia

- Pygmy Sperm Whale, Kogia breviceps

- Indo-Pacific Dwarf Sperm Whale, Kogia sima

- Atlantic Dwarf Sperm Whale, - Kogia ssp.

- Genus Kogia

- Superfamily Platanistoidea: River dolphins

- Family Iniidae

- Genus Inia

- Amazon River Dolphin, Inia geoffrensis

- Genus Inia

- Family Lipotidae - MSW3 treats Lipotes as a member of Iniidae

- Genus Lipotes

- † Baiji, Lipotes vexillifer

- Genus Lipotes

- Family Pontoporiidae - MSW3 treats Pontoporia as a member of Iniidae

- Genus Pontoporia

- Franciscana, Pontoporia blainvillei

- Genus Pontoporia

- Family Platanistidae

- Genus Platanista

- Ganges and Indus River Dolphin, Platanista gangetica. MSW3 treats Platanista minor as a separate species, with common names Ganges River Dolphin and Indus River Dolphin, respectively.

- Genus Platanista

- Family Iniidae

- Family Ziphidae, Beaked whales

- Genus Berardius

- Arnoux's Beaked Whale, Berardius arnuxii

- Baird's Beaked Whale (North Pacific Bottlenose Whale), Berardius bairdii

- Subfamily Hyperoodontidae

- Genus Hyperoodon

- Northern Bottlenose Whale, Hyperoodon ampullatus

- Southern Bottlenose Whale, Hyperoodon planifrons

- Genus Indopacetus

- Indo-Pacific Beaked Whale (Longman's Beaked Whale), Indopacetus pacificus

- Genus Mesoplodon, Mesoplodont Whale

- Sowerby's Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon bidens

- Andrews' Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon bowdoini

- Hubbs' Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon carlhubbsi

- Blainville's Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon densirostris

- Gervais' Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon europaeus

- Ginkgo-toothed Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon ginkgodens

- Gray's Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon grayi

- Hector's Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon hectori

- Layard's Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon layardii

- True's Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon mirus

- Perrin's Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon perrini. This species was recognized in 2002 and as such is listed by MSW3 but not Rice.

- Pygmy Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon peruvianus

- Stejneger's Beaked Whale, Mesoplodon stejnegeri

- Spade Toothed Whale, Mesoplodon traversii

- Genus Hyperoodon

- Genus Tasmacetus

- Tasman Beaked Whale (Shepherd's Beaked Whale), Tasmacetus shepherdi

- Genus Ziphius

- Cuvier's Beaked Whale, Ziphius cavirostris

- Genus Berardius

- Family Delphinidae: Dolphin

- Suborder Mysticeti: Baleen whales

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Grzimek, B., D. G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M. C. McDade. 2004. Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale. ISBN 0787657883.

- Mead, J. G., and R. L. Brownell. 2005. Order Cetacea. In D. E. Wilson and D. M. Reeder, eds., Mammal Species of the World, 3rd edition. Johns Hopkins University Press. Pp. 723-743. ISBN 0-801-88221-4.

- Rice, D. W. 1998. Marine Mammals of the World: Systematics and Distribution. Lawrence, KS: Society for Marine Mammalogy. ISBN 1891276034.

- Wilson, D. E., and D. M. Reeder. 1993. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1560982179.

| Mammals |

|---|

| Monotremata (platypus, echidnas) |

Marsupialia: | Paucituberculata (shrew opossums) | Didelphimorphia (opossums) | Microbiotheria | Notoryctemorphia (marsupial moles) | Dasyuromorphia (quolls and dunnarts) | Peramelemorphia (bilbies, bandicoots) | Diprotodontia (kangaroos and relatives) |

Placentalia: Cingulata (armadillos) | Pilosa (anteaters, sloths) | Afrosoricida (tenrecs, golden moles) | Macroscelidea (elephant shrews) | Tubulidentata (aardvark) | Hyracoidea (hyraxes) | Proboscidea (elephants) | Sirenia (dugongs, manatees) | Soricomorpha (shrews, moles) | Erinaceomorpha (hedgehogs and relatives) Chiroptera (bats) | Pholidota (pangolins)| Carnivora | Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) | Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates) | Cetacea (whales, dolphins) | Rodentia (rodents) | Lagomorpha (rabbits and relatives) | Scandentia (treeshrews) | Dermoptera (colugos) | Primates | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 01:55:17 | 135 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Cetacea | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF