Thugs

From Nwe

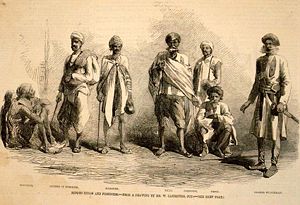

From Nwe The Thugs (originally called Thuggee or Tuggee meaning "deceivers") were an Indian network of secret fraternities engaged in murdering and robbing travellers. The Thuggee groups consisted both of Hindus and Muslims though their patron deity was the Hindu Goddess Kali.[1] Some writers classify the thugs as a religious cult or sect.[2] They operated from as early as the thirteenth century until they were suppressed by the British the nineteenth century.

Etymology

The word "Thug" derives from the Hindi term thag (thief), which itself comes from Sanskrit sthagati (to conceal). The term "thug" eventually passed into common English during the time of British Imperial rule of India and still denotes a brutality to this day.

History

The earliest authenticated mention of the Thugs is found in the following passage of Ziau-d din Barni's History of Firoz Shah (written about 1356):

- In the reign of that sultan (about 1290), some Thugs were taken in Delhi, and a man belonging to that fraternity was the means of about a thousand being captured. But not one of these did the sultan have killed. He gave orders for them to be put into boats and to be conveyed into the lower country, to the neighborhood of Lakhnauti, where they were to be set free. The Thugs would thus have to dwell about Lakhnauti and would not trouble the neighborhood of Delhi any more."[3]

Though they themselves trace their origin to seven Muslim tribes, the Hindu followers only seem to be related during the early periods of Islamic development; at any rate, their religious creed and staunch worship of Kali, one of the Hindu Tantric Goddesses, showed no Islamic influence. Assassination for gain was a religious duty for them, and was considered a holy and honorable profession, in which moral feelings did not come into play. The practice of Thuggee was categorically stamped out by the British by the early nineteenth century.

Induction was sometimes passed from father to son; the leaders of the thug groups tended to come from these hereditary lines. Another way by which people became thugs was this; sometimes the thugs did not kill the young children of the travellers and groomed them to become thugs themselves. Some men became thugs to escape great poverty. A fourth way of becoming a thug was by learning it from an guru.[1]

The Thuggee cult was eventually suppressed by the British rulers of India in 1828,[1] due largely to the efforts of Lord William Bentinck, Governor General of India from 1828, who started an extensive campaign involving profiling, intelligence, and executions. The campaign was heavily based on informants recruited from captured thugs who were offered protection on the condition that they told everything that they knew. By the 1870s, the Thug cult was extinct, but the concept of 'criminal tribes' and 'criminal castes' is still in use in India.[4] A police organization known as the 'Thuggee and Dacoity Department' was established within the Government of India, with William Sleeman appointed Superintendent of the department in 1835. The Department remained in existence until 1904, when it was replaced by the Central Criminal Intelligence Department. The defeat of the Thuggees played a part in securing Indian loyalty to the British Raj.

Previous attempts at prosecuting and eliminating the thugs had been largely unsuccessful due to the lack of evidence for their crimes. The thugs' modus operandi yielded very little evidence: no witnesses, no weapons, and no corpses. Besides, the thugs usually made no confessions when captured. Another main reason was the fact that thug groups did not act locally, but all over the Indian subcontinent, including territories that did not belong to British India in combination with the fact that there was then no centralized criminal intelligence agency.

Beliefs

According to nineteenth-century writings about Thuggee, the will of the goddess by whose command and in whose honor they followed their calling was revealed to them through a very complicated system of omens. The colonial writings further state that in obedience to these, they often traveled hundreds of miles in company with, or in the wake of, their intended victims before a safe opportunity presented itself for executing their design. When the deed was done, rites were performed in the deity's honor, and a significant portion of the spoils was set apart for Her.

They believed each murder prevented Kali's arrival for one millennium. The fraternity also possessed a jargon of their own, the cant Ramasi, as well as certain signs by which its members recognized each other in the most remote parts of India. Even those who, from age or infirmities, could no longer take an active part in the ritual murder continued to aid the cause as watchers, spies, or dressers of food. Because of their thorough organization, the secrecy and security of their operation, and the religious pretext in which they shrouded their murders, they were recognized as a regular tax-paying profession and continued for centuries to practice their craft, free of inquiry from Hindu rulers.

It should be noted that even at the time, a very small minority of the followers of Kali were Thuggees, whereas the majority of followers did not share the Thuggee viewpoint.

Activities

The Thugs were a well-organized confederacy of professional assassins who traveled in various guises through India in gangs of ten to 200, worming themselves into the confidence of wayfarers of the wealthier class. When a favorable opportunity arose, the Thug strangled his victim by throwing a yellow scarf or Rumaal, symbolic of Kali, around the neck, and then plundered and buried him. All this was done according to certain ancient and rigidly prescribed forms, and after the performance of special religious rites, in which the consecration of the pickaxe and the sacrifice of sugar formed a prominent part. The pickaxe was a necessary tool to dig graves. Because they used strangulation as the method of murder they were also frequently called "Phansigars," or "noose-operators."

Thuggee groups practiced robbery and murder of travellers. Their modus operandi was to befriend unsuspecting travellers and win their trust; when the travellers allowed the thugs to join them, the group of thugs killed them at a suitable place and time before robbing them. Their method of killing was very often strangulation. Usually two or three thugs were used to strangle one traveller. The thugs hid the corpses, often by burying them or by throwing them into wells.[1]

Thugs preferred to kill their victims at certain suitable places, called beles, that they knew well. They killed their victims usually in darkness while the thugs made music or noise to escape discovery. Each member of the group had its own function, like luring travelers with charming words or that of guardians to prevent escape of victims while the killing took place. The leader of a gang was called jamaadaar.

Victims

Estimates of the total number of victims depend heavily on the estimated length of existence of the thugs for which there are no reliable sources. According to the 1979 Guinness Book of Records the Thuggee cult was responsible for approximately 2,000,000 deaths.[5] The British historian Dr. Mike Dash estimated that they killed 50,000 persons in total, based on his assumption that they only started to exist 150 years before their eradication in the 1830s.[1]

Yearly figures for the early nineteenth century are better documented, but even they are inaccurate estimates. For example, gang leader Behram has often been considered to be the world's most prolific serial killer with 931 killings between 1790 and 1830 attributed to him.[5] Reference to contemporary manuscript sources, however, shows that Behram actually gave inconsistent statements regarding the number of murders he had committed, and that while he did state that he had "been present at" more than 930 killings committed by his gang of 25-50 men, elsewhere he admitted that he had personally strangled around 125 people. Having turned King's Evidence and agreed to inform on his former companions, furthermore, Behram never stood trial for any of the killings attributed to him, the total of which must thus remain a matter of dispute.[6]

Possible misinterpretation of Thuggee by the British

In her book The Strangled Traveler: Colonial Imaginings and the Thugs of India (2002), Martine van Woerkens suggests that evidence for the existence of a Thuggee cult in the nineteenth century was in part the product of "colonial imaginings"—British fear of the little-known interior of India and limited understanding of the religious and social practices of its inhabitants.

Krishna Dutta, while reviewing the book Thug: the true story of India's murderous cult by the British historian Dr. Mike Dash in The Independent, argues:[7]

- "In recent years, the revisionist view that Thugee was a British invention, a means to tighten their hold in the country, has been given credence in India, France and the US, but this well-researched book objectively questions that assertion."

In his book, Dash rejects skepticism about the existence of a secret network of groups with a modus operandi that was different from highwaymen, such as dacoits. To prove his point, Dash refers to the excavated corpses in graves, of which the hidden locations were revealed to Sleeman's team by thug informants. In addition, Dash treats the extensive and thorough documentation that Sleeman made. Dash rejects the colonial emphasis on the religious motivation for robbing, but instead asserts that monetary gain was the main motivation for Thuggee and that men sometimes became thugs due to extreme poverty. He further asserts that the Thugs were highly superstitious and that they worshipped the Hindu goddess Kali, but that their faith was not very different from their contemporary non-thugs. He admits, though, that the thugs had certain group-specific superstitions and rituals.

In popular culture

In literature

- The story of Thuggee was popularized by books such as Philip Meadows Taylor's novel Confessions of a Thug, 1839, leading to the word "thug" entering the English language. Ameer Ali, the protagonist of Confessions of a Thug was said to be based on a real Thug called Syeed Amir Ali.

- John Masters' novel The Deceivers also deals with the subject. A more recent book is George Bruce's The Stranglers: The cult of Thuggee and its overthrow in British India (1968). Dan Simmons's Song of Kali, 1985, features a Thuggee cult.

- The nineteenth century American writer Mark Twain discusses the Thuggee fairly extensively in chapters 9 and 10 of "Following the Equator: Volume II," 1897, THE ECCO PRESS, ISBN 0-88001-519-5.

- Christopher Moore's novel, Lamb: The Gospel According to Biff, Christ's Childhood Pal, describes a Thuggee ritual.

- Sci-Fi/Fantasy author Glen Cook uses an India-like setting and Thuggee as a plot vehicle in his books Shadow Games (June 1989), and Dreams of Steel (April 1990). The books and later ones that continue the storyline form part of Cook's Black Company series.

- The Serpent's Shadow by Mercedes Lackey has a Hindu villain, whose minions are Thuggee, almost without exception.

- Author William T. Vollmann draws upon Sleeman in his story The Yellow Sugar, which is one of two tales in his collection The Rainbow Stories dealing with the color yellow.

- Arthur Conan Doyle attributes the disfigurements of the protagonist in his Sherlock Holmes novel The Adventure of the Crooked Man to his capture and torture by Thuggee rebels during the British occupation of India.

- Italian writer Emilio Salgari (1862-1911) wrote about thugs in I Misteri della Jungla Nera (1895) and Le Due Tigri (1904) and other short stories.

- Francisco Luís Gomes's novel (in Portuguese language), Os Brahamanes (1866), describes Thuggee rituals, while Magnod, the main character, joins in group.

- Greg Iles developed one of the lead antagonists of his book, Mortal Fear, using the Thuggee as an explanation of the historically violent past the antagonist lead.

In film

- The two most popular depictions of the Thugs in film are the 1939 film, Gunga Din and the 1984 film, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. The Indiana Jones movie is notable for Amrish Puri's villain, chanting lines such as "maaro maaro sooar ko, chamdi nocho pee lo khoon" meaning "Kill, Kill the pig, flay his skin, drink his blood." ..Temple of Doom was temporarily banned in India for an alleged racist portrayal of Indians. Both films have the heroes fighting secret revivals of the cult to prevent them from resuming their reigns of terror.

- In the 1956 film Around the World in Eighty Days, starring David Niven, Passepartout rescues a princess captured by the Thugee and sentenced to burn to death in the funeral pyre with her deceased husband.

- In 1959, legendary British horror studio Hammer Film Productions released The Stranglers of Bombay. In the film, Guy Rolfe portrays an heroic British officer battling institutional mismanagement by the British East India Company, as well as Thuggee infiltration of Indian Society, in an attempt to bring the cultists to justice.

- In 1965, Thuggee were portrayed with bumbling malevolence in the Beatles film "Help!".

- The 1968 Indian film Sangharsh, based on a story by Jnanpith Award winner Mahasweta Devi, presented the depiction of Thuggees that is considered to be very accurate.

- The 1988 film version of The Deceivers, produced by Ismail Merchant and starring Pierce Brosnan, is a fictionalized account of the initial discovery and infiltration of the Thuggee sect by an imperial British administrator.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Dash.

- ↑ Rushby

- ↑ Elliot, 141.

- ↑ Thugs Traditional View (shtml). BBC. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 McWhirter.

- ↑ Paton.

- ↑ Krishna Dutta, 2005, The sacred slaughterers. Book review of Thug: the true story of India's murderous cult by Mike Dash. In the Independent (Published: 8 July 2005) Online text Retrieved April 2, 2008.

Bibliography

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Dash, Mike. Thug: the true story of India's murderous cult. Granta Books, 2005. ISBN 978-1862076044

- Dutta, Krishna. 2005. The sacred slaughterers. Book review of Thug: the true story of India's murderous cult by Mike Dash. In the Independent (Published: 8 July 2005) Online text Retrieved April 2, 2008.

- Elliot, Henry Miers. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period. Volume 3 Adamant Media Corporation, 2001. ISBN 978-0543947123

- McWhirter, Norris. Guinness Book of World Records 1979 Edition. Bantam, 1979. ISBN 978-0553123708

- Paton, James. 'Collections on Thuggee and Dacoitee'. British Library Add. Mss. 41300.

- Rushby, Keven. Children of Kali: Through India in Search of Bandits, the Thug Cult, and the British Raj. Walker & Company, 2003. ISBN 978-0802714183

- Woerkens, Martine van and Catherine Tihanyi. The Strangled Traveler: Colonial Imaginings and the Thugs of India. University Of Chicago Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0226850863

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 03:56:48 | 188 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Thugs | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF