Ashkenazi

From Nwe

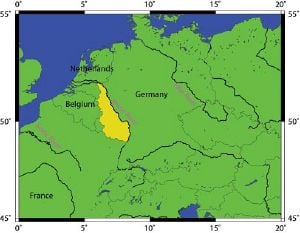

From Nwe Ashkenazi Jews, also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim, are Jews descended from the medieval Jewish communities of the Rhineland—"Ashkenaz" being the Medieval Hebrew name for Germany. They are distinguished from Sephardic Jews, the other main group of European Jewry, who arrived earlier in Europe and lived primarily in Spain.

Many Ashkenazim later migrated, largely eastward, forming communities in Germany, Hungary, Poland, Russia, Eastern Europe, and elsewhere between the tenth and nineteenth centuries. From medieval times until the mid-twentieth century, the lingua franca among Ashkenazi Jews was primarily Yiddish.

The Ashkenazi Jews developed a distinct liturgy and culture, influenced to varying degrees, by interaction with surrounding peoples, predominantly Germans, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, Kashubians, Hungarians, Ukrainians, Lithuanians, Letts, Belarusians, and Russians.

Although in the eleventh century they comprised only three percent of the world's Jewish population, Ashkenazi Jews accounted for 92 percent of the world's Jews in 1931, and today make up approximately 80 percent of Jews worldwide. Most Jewish communities with extended histories in Europe are Ashkenazim, with the exception of Sephardic Jews associated with the Mediterranean region. A significant portion of the Jews who migrated from Europe to other continents in the past two centuries are Eastern Ashkenazim, particularly in the United States. Ashkenazi Jews have made major contributions to world culture in terms of science, literature, economics, and the arts.

Origins of Ashkenazim

| Ashkenazi Jews (יהודי אשכנז Yehudei Ashkenaz) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8- 11.2 million (estimate) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Yiddish, Hebrew, Russian, English | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religions | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Judaism | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sephardi Jews, Mizrahi Jews, and other Jewish ethnic divisions |

Ashkenaz is a Medieval Hebrew name for Germany. European Jews came to be called "Ashkenaz" because the main centers of Jewish learning were located in Germany.

The Ashkenazi Jewish population originated in the Middle East. When they arrived in northern France and the Rhineland sometime around 800-1000 C.E., the Ashkenazi Jews brought with them both Rabbinic Judaism and the Babylonian Talmudic culture that underlies it. Yiddish, once spoken by the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jewry, is a Jewish language which developed from the Middle High German vernacular, heavily influenced by Hebrew and Aramaic.

Background in the Roman Empire

After the forced Jewish exile from Jerusalem in 70 C.E. and the complete Roman takeover of Judea following the Bar Kochba rebellion of 132-135 C.E., Jews continued to be a majority of the population in Palestine for several hundred years. In Palestine and Mesopotamia, where Jewish religious scholarship was centered, the majority of Jews were still engaged in farming. Trade was also a common occupation, facilitated by the easy mobility of traders through the dispersed Jewish communities.

In the late Roman Empire, small numbers of Jews are known to have lived in Cologne and Trier, as well as in what is now France. However, it is unclear whether there is any continuity between these late Roman communities and the distinct Ashkenazi Jewish culture that began to emerge about 500 years later.

Rabbinic Judaism moves to Ashkenaz

In Mesopotamia and in Persian lands free of Roman imperial domination, Jewish life had a long history. Since the conquest of Judea by Nebuchadnezzar II in the early sixth century B.C.E., "Babylonian Jews" had always been the leading diaspora community, rivaling the leadership of Palestine. When conditions for Jews began to deteriorate in the western Roman Empire, many of the religious leaders of Judea and Galilee fled to the east. At the academies of Pumbeditha and Sura near Babylon, Rabbinic Judaism based on talmudic learning began to emerge and assert its authority over Jewish life throughout the diaspora. Rabbinic Judaism also created a religious mandate for literacy, requiring all Jewish males to learn Hebrew and read from the Torah. This emphasis on literacy and learning a second language would eventually be of great benefit to the Jews, allowing them to take on commercial and financial roles within Gentile societies where literacy was often quite low.

After the Islamic conquest of the Middle East and North Africa, new opportunities for trade and commerce opened between the Middle East and Western Europe. The vast majority of Jews in the world now lived in Islamic lands. Urbanization, trade, and commerce within the Islamic world allowed Jews to abandon farming and live in cities, engaging in occupations where they could use their skills. The influential, sophisticated, and well-organized Jewish community of Mesopotamia, now centered in Baghdad, became the center of the Jewish world. In the Caliphate of Baghdad, Jews took on many of the financial occupations that they would later hold in the cities of Ashkenaz. Jewish traders from Baghdad began to travel to the west, renewing Jewish life in the western Mediterranean region. They brought with them Rabbinic Judaism and Babylonian Talmudic scholarship.

After 800 C.E., Charlemagne's unification of former Frankish lands with northern Italy and Rome brought on a brief period of stability and unity in Western Europe. This created opportunities for Jewish merchants to settle north of the Alps. Charlemagne granted the Jews in his lands freedoms similar to those once enjoyed under the ancient Roman Empire. In Frankish lands, many Jewish merchants took on occupations in finance and commerce, including moneylending or usury. (Church legislation banned Christians from lending money to fellow Christians in exchange for interest.) Although the Sephardic community in Islamic Spain was far better established at first, by the eleventh century, when the great rabbinic sage Rashi of Troyes wrote his talmudic commentaries, Ashkenazi Jews had emerged as a strong community capable of major cultural contributions to Jewish civilization.

DNA clues

Efforts to identify the origins of Ashkenazi Jews through DNA analysis began in the 1990s. Like most DNA studies of human migration patterns, these studies have focused on two segments of the human genome, the Y chromosome (inherited only by males), and the mitochondrial genome (DNA which passes from mother to child). Both segments are unaffected by recombination. Thus, they provide an indicator of paternal and maternal origins, respectively.

Recent research indicates that a significant portion of Ashkenazi maternal ancestry is also of Middle Eastern origin. A 2006 study by Behar et al. [2] suggested that about 40 percent of the current Ashkenazi population is descended matrilineally from just four women. These four "founder lineages" were "likely from a Hebrew/Levantine mtDNA pool" originating in the Near East in the first and second centuries C.E.

Ashkenazi migrations

Historical records show evidence of Jewish communities north of the Alps and Pyrenees as early as the eighth and ninth century, especially in the Rhineland area, where they at first established trading establishments and later more settled communities under the protection of feudal lords. By the early 900s, Jewish populations were well-established in Northern Europe and later followed the Norman Conquest into England in 1066, also settling in the Rhineland. With the onset of the Crusades and the expulsions of Jews from England (1290), France (1394), and parts of Germany (1400s), Jewish migration pushed eastward into Poland, Lithuania, and Russia.

Due to Christian European prohibitions restricting certain land ownership and guild membership by Jews, Jewish economic activity was focused on trade, business management, and financial services.

By the 1400s, the Ashkenazi Jewish communities in Poland were the largest Jewish communities of the diaspora. Poland at this time was a decentralized medieval monarchy, incorporating lands from Latvia to Romania, including much of modern Lithuania and Ukraine. This area, which eventually fell under the domination of Russia, Austria, and Prussia (Germany), would remain the main center of Ashkenazi Jewry until the Holocaust.

Customs, laws and traditions

The collective corpus of Jewish religious law, including biblical law and later, Talmudic and rabbinic customs and traditions of Ashkenazi Jews may differ from those of Sephardi Jews, particularly in matters of custom.

Well-known differences in practice include:

- Observance of Passover: Ashkenazi Jews traditionally—though less so recently—refrain from eating legumes, corn, millet, and rice, whereas Sephardi Jews typically do not prohibit these foods.

- Ashkenazi Jews freely mix and eat fish and milk products; some Sephardic Jews refrain from doing so, considering fish to be included in the category of "meat," which Talmudic tradition says cannot be mixed with milk.

- Ashkenazim are also somewhat more liberal in other matters related to Jewish dietary law for the proper preparation of kosher meat.

- Ashkenazim are more permissive than Sephardim toward the usage of wigs, rather than scarves and shawls, as a hair covering for married and widowed women.

- Ashkenazi Jews frequently name newborn children after deceased family members, but not after living relatives. Sephardi Jews, on the other hand, often name their children after the children's grandparents, even if those grandparents are still living.

- Ashkenazi tefillin (the two boxes containing Biblical verses and the leather straps attached to them which are used in traditional Jewish prayer) bear some differences from Sephardic tefillin. In the traditional Ashkenazic rite, the tefillin are wound towards the body, not away from it. Ashkenazim traditionally don tefillin while standing whereas other Jews generally do so while sitting down.

- Ashkenazic traditional pronunciations of Hebrew differ from those of other groups.

Who is an Ashkenazi Jew?

An Ashkenazi Jew can be defined religiously, culturally, or ethnically. Since the overwhelming majority of Ashkenazi Jews no longer live in Eastern Europe, the isolation that once fostered their distinct religious tradition and culture has vanished. Furthermore, the word "Ashkenazi" is itself evolving and taking on new meanings.

In a religious sense, an Ashkenazi Jew is any Jew whose family tradition and ritual follows Ashkenazi practice. When the Ashkenazi community first began to develop, the centers of Jewish religious authority were in the Islamic world, at Baghdad and in Islamic Spain. Ashkenaz (Germany) was so distant geographically that it developed a tradition of its own, and Ashkenazi Hebrew came to be pronounced in ways distinct from other forms of Hebrew.

In a cultural sense, an Ashkenazi Jew can be identified by the concept of Yiddishkeit, a word that literally means “Jewishness” in the Yiddish language. Originally this meant the study of Torah and Talmud for men, and a family and communal life governed by the observance of Jewish Law for men and women. From the Rhineland to Riga to Romania, most Jews prayed in liturgical Ashkenazi Hebrew, and spoke some dialect of Yiddish in their secular lives.

However, with modernization, Yiddishkeit began to encompass not just Orthodoxy and Hasidism, but a broad range of movements, ideologies, practices, and traditions in which Ashkenazi Jews have participated and somehow retained a sense of Jewishness. As Ashkenazi Jews moved away from Eastern Europe, settling mostly in North America and Israel, the geographic isolation which gave rise to Ashkenazim has given way to mixing with other cultures, and with non-Ashkenazi Jews who, similarly, are no longer isolated in distinct geographic locales. In Israel, Hebrew has replaced Yiddish as the primary Jewish language for the vast majority of Ashkenazi Jews.

By tradition, Jewish status is inherited through the maternal lineage. Therefore, someone who is descended from a Jewish mother, even if totally unaware of their Jewish heritage, is a Jew. A large proportion of Ashkenazi Jews in Israel, the U.S., and the former Soviet Union are not religiously observant. Even a Jew who converts to another religion, though an apostate, is still considered a Jew. Karl Marx, an atheist whose Jewish mother and father had converted to Christianity before he was born, was an Ashkenazi Jew.

In an ethnic sense, an Ashkenazi Jew is one whose ancestry can be traced to the Jews of central and Eastern Europe. For roughly a thousand years, the Ashkenazi Jews were a reproductively isolated population in Europe. However, since the middle of the twentieth century, many Ashkenazi Jews have intermarried, both with members of other Jewish communities and with people of other nations and faiths. Conversion to Judaism, rare for nearly 1500 years, has once again become common. Thus, the concept of Ashkenazi Jews as a distinct ethnic people, especially in ways that can be defined ancestrally and therefore traced genetically, has also blurred considerably.

In Israel, Jews of mixed background are increasingly common, partly because of intermarriage between Ashkenazi and non-Ashkenazi partners, and partly because some do not identify with such historic markers as relevant to their life experiences as Jews. Religious Ashkenazi Jews living in Israel are obliged to follow the authority of the chief Ashkenazi rabbi in halakhic matters.

Modern history

In an essay on Sephardi Jewry, Daniel Elazar at the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs summarized the demographic history of Ashkenazi Jews in the last thousand years, noting that at the end of the eleventh century, 97 percent of world Jewry was Sephardic and 3 percent Ashkenazi; in the mid-seventeenth century, "Sephardim still outnumbered Ashkenazim three to two," but by the end of the eighteenth century "Ashkenazim outnumbered Sephardim three to two, the result of improved living conditions in Christian Europe versus the Muslim world. "By 1931, Ashkenazi Jews accounted for nearly 92 percent of world Jewry.

Ashkenazi Jews developed the Hasidic movement as well as major Jewish academic centers across Poland, Russia, and Lithuania in the generations after emigration from the west. After two centuries of comparative tolerance in the new nations, massive westward emigration occurred in the 1800s and 1900s in response to pogroms and the economic opportunities offered in other parts of the world. Ashkenazi Jews have made up the majority of the American Jewish community since 1750. Ashkenazi cultural growth led to the Haskalah or Jewish Enlightenment, and the development of Zionism in modern Europe.

However, Ashkenazi Jews were the primary victims of the Nazi campaign to eradicate European Jewry. Of the estimated 8.8 million Jews living in Europe at the beginning of World War II, the majority of whom were Ashkenazi, about six million—more than two-thirds—were systematically murdered in the Holocaust. These included three million of 3.3 million Polish Jews (91 percent); 900,000 of 1.1 million in Ukraine (82 percent); and 50 to 90 percent of the Jews of other Slavic nations, Germany, France, Hungary, and the Baltic states. The only non-Ashkenazi community to have suffered similar depletions were the Jews of Greece. Many of the surviving Ashkenazi Jews emigrated to countries such as Israel, Australia, and the United States after the war.

Today, Ashkenazi Jews constitute approximately 80 percent of world Jewry, but probably less than half of Israeli Jews. Nevertheless they have traditionally played a prominent role in the media, economy, and politics of Israel. Tensions have sometimes arisen between the mostly Ashkenazi elite whose families founded the state, and later migrants from various non-Ashkenazi groups.

Achievement

Ashkenazi Jews have a noted history of achievement in western societies. They have won a disproportionate share of major academic prizes, such as the Nobel awards and the Fields Medal in mathematics. In those societies where they have been free to enter any profession, they have a record of high occupational achievement, entering professions and fields of commerce where higher education is required. Ashkenazim have also made major contributions in literature, economic leadership, and the arts.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gabriel E. Feldman,

PDF , Israel Medical Association Journal, Volume 3, 2001.

PDF , Israel Medical Association Journal, Volume 3, 2001. - ↑ Doron M. Behar and Ene Metspalu, Toomas Kivisild, Alessandro Achilli, Yarin Hadid, Shay Tzur, Luisa Pereira, Antonio Amorim, Lluı's Quintana-Murci, Kari Majamaa, Corinna Herrnstadt, Neil Howell, Oleg Balanovsky, Ildus Kutuev, Andrey Pshenichnov, David Gurwitz, Batsheva Bonne-Tamir, Antonio Torroni, Richard Villems, and Karl Skorecki. "The Matrilineal Ancestry of Ashkenazi Jewry: Portrait of a Recent Founder Event." In The American Journal of Human Genetics (7 (3) (March, 2006): 487-497, PMID 16404693

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beider, Alexander. A Dictionary of Ashkenazic Given Names: Their Origins, Structure, Pronunciations, and Migrations. Avotaynu, 2001. ISBN 1886223122

- Biale, David. Cultures of the Jews: A New History. Schoken Books, 2002. ISBN 0805241310

- Goldberg, Harvey E. The Life of Judaism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001. ISBN 0520212673

- Silberstein, Laurence. Mapping Jewish Identities. New York University Press, 2000. ISBN 0814797695

- Vital, David. A People Apart: A History of the Jews in Europe. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0198219806

- Wettstein, Howard. Diasporas and Exiles: Varieties of Jewish Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0520228642

External links

All links retrieved November 7, 2021.

- Ashkenazim by Shira Schoenberg. www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org.

- A Reassessment of the DNA Evidence by Ellen Levy-Coffman. jogg.info.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 03:25:02 | 254 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Ashkenazi | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF