Roman Emperor

From Rationalwiki

From Rationalwiki | Tomorrow is a mystery, but yesterday is History |

| Secrets of times gone by |

Although most rulers of ancient Rome were not emperors, the term Roman emperors has become the accepted name for the various kings, first citizens and variously-titled autocrats who ran the place from Julius Caesar onwards. The term "emperor" derives from the Latin imperator and from the Roman emperor's role as Rome's supreme military commander (even if in the actual campaigns, field commands were often delegated to particular generals). The history of the Roman Empire is usually divided into the early Principate, when the emperor was expected to be the first among equals ("primus inter pares"), and the later Dominate (when emperors were not even expected to keep up republican appearances).

The individual Roman emperors were a varied lot, ranging from the wise and thoughtful (Marcus Aurelius, Trajan, Nerva, Antonius Pius) to the cruel but competent (Augustus, Diocletian, Justinian, Julius Caesar) to the insane and tyrannical (pretty much everyone else). It is difficult to judge precisely how bad a given emperor may or may not have been.[note 1] Most died due to assassination, and there is considerable motivation to make the ruler look as bad as possible post-mortem. Furthermore, in ancient Rome, only three general patterns were accepted for biographies: Either the shining hero through and through, the vile tyrant through and through, or someone who initially showed promise but then degenerated. Nero and Caligula, interestingly, are both described as the latter by all available sources. Because of this, ancient sources must be read with a skeptical eye. The emperors replaced the Roman republic with an ad hoc system of government by decree, using and abusing religion, the army, and the Senate to maintain and extend their power.

Military strongmen during the Republic[edit]

The late Republic was dominated by several statesmen (often consuls or former consuls) who used their military power to seize almost absolute control over Rome during a crisis. The Empire itself can be seen as a simple institutionalization of this practice. The early empire (called the principate) was designed to simultaneously give absolute power to a single person while maintaining the Republic's illusion. [1] To more fully understand the Empire, it is necessary to discuss two significant military rulers.

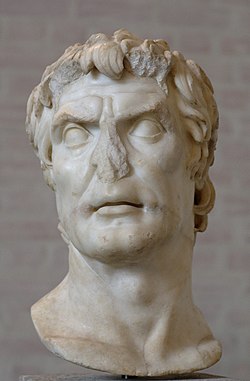

Sulla[edit]

Lucius Cornelius Sulla (138 BCE–78 BCE) was born to a prominent patrician family, ensuring that his sympathies would always lie with the aristocratic and conservative optimates. He had served under the famed Roman consul Gaius Marius in wars against Germanic and North African tribes and was instrumental in helping Rome win these wars. At the same time, Marius got much of the credit Sulla thought he was due, though he was elected consul in 88 BCE. Eventually, a law granting Italians Roman citizenship was passed under his care. He was forced to flee Rome during the political violence that followed. [note 2] Sulla responded to this by going to his old army, assuming command of it, and proceeding to take Rome by storm with his legions, which was unprecedented in Roman history. After leaving to fight a rebellion in Greece, Marius returned to assume control of the Republic until he died in 84. Sulla returned to Rome, re-recaptured the city, and proceeded to declare himself dictator legibus faciendis et reipublicae constituendae causa, or "dictator for the making of laws and for the settling of the constitution", before enacting a series of proscriptions against his remaining political opponents (mainly from the reformist Populares faction). Thousands were killed amidst Sulla's reign of terror, with their property confiscated and given to Sulla and his cronies for sale. [2] Sulla also enacted a series of constitutional and legal reforms, which included stripping the plebian tribunes of most of their powers, doubling the size of the Senate to 600 people, giving it a monopoly over judicial affairs, and creating a series of criminal courts. Sulla resigned his dictatorship after that, was elected consul for 80 BCE, and then retired to his farm to write his memoirs.

Sulla was committed to the Republic, as evidenced by his resignation from the dictatorship. However, his rule would ultimately prove that the main thing that mattered in Roman politics is who had the most soldiers, not the most votes. This would become a recurring theme throughout the late Republic, as well as the mid-to late-Empire.

Fun fact, one of the young reformers to escape his proscriptions was the second guy on this list, who would learn from Sulla's efforts and use them in his bid for power.

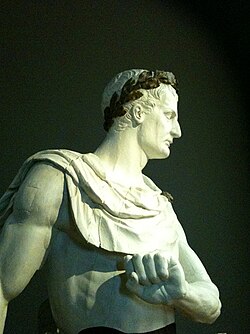

Julius Caesar[edit]

Gaius Julius Caesar (100 BCE–44 BCE) was a Roman conqueror who extended the borders of the Roman Republic across much of Western Europe. However, the Senate feared him and tried to restrict his growing power. Caesar initiated a civil war and quickly took possession of Rome and the surrounding Italian countryside while the anti-Caesar faction of the Senate fled to Greece with Pompey. The remaining Senators appointed Caesar dictator-for-life. The civil war sputtered on while Caesar took a side trip to Egypt and hooked up with Cleopatra, but eventually, Caesar won. Magnanimous in victory, Caesar pardoned and restored his former enemies to the Senate. Still, they paid him back with a bold and public assassination in the Senate chamber the following March 15. There were so many conspirators, they actually injured each other. A myth about Caesar was that he was a great military strategist. He was more of a political leader, often delegating the fieldwork to his lieutenants and taking advantage of openings given by his men. Courage and charisma were some of his most essential tools on the battlefield; he was a genuinely great warrior who often raised his soldiers' morale by fighting on the front lines alongside his men.

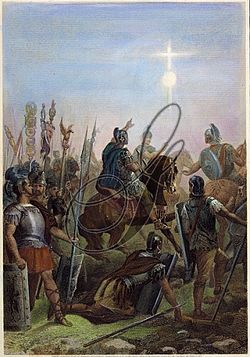

During the games held eleven days after the Ides of March to honor Julius Caesar, a bright comet appeared in the sky, and Octavian said this was "proof" his father was made into a god. This superstition was instrumental in helping Octavian sway Caesar's legions to his side. Later, many emperors were deified following their deaths, leading to the institution of the "imperial cult."

Julius Caesar laid down the original blueprint for using social and political chaos to overthrow a democratic republic and install authoritarian rule. As dictators went, Caesar wasn't all bad. He initiated a series of social reforms, including a new calendar and regulating the number of grain "welfare" recipients. He tried but failed to obtain land in Italy for his legion veterans to retire on, leaving it for his successor. Caesar was not actually the first Roman Emperor, but he cleared the way for his adopted son Octavian to lay the Republic on the ash heap of history as "First Citizen" of the Roman Empire, Augustus.[citation needed]

Quotes[edit]

- Veni, vidi, vici ("I came, I saw, I conquered") - after the conquest of Gaul.

- Alea iacta est ("the die is cast") - after crossing the Rubicon.

- Et tu, Brute? ("and you, Brutus?") - in William Shakespeare's Julius Caesar (play)

.

. - "Infamy! Infamy! They've all got in in for me!" - in Carry on Cleo

.

.

Emperors[edit]

These are the Roman rulers granted the title of imperator (translates to, well, "emperor" now, but it used to mean "commander") among others, such as princeps civitatis ("first man of the state").

Augustus (27 BCE–14 CE)[edit]

Tiberius (14–37 CE)[edit]

Cruel and perverted. He paid young boys to swim in his pool and bite him.

To be fair, his 23-year reign wasn't actually that bad. The first two-thirds or so of his reign went remarkably well, considering he was the first emperor after Augustus. It wasn't totally certain how things would proceed — surprisingly, there was no civil war, as had been typical in the past. He was able to consolidate the empire, and rather than continue slaughtering people and conquering neighboring lands, chose instead to fortify the borders and work on developing the economy. When he died, he left the imperial treasury with a massive surplus (which his successor made quickly disappear...). However, the good times were not to last.

First, his personality was completely wrong for the job. He hated politics and politicking and tended to be very reserved, even seclusive, which are not desirable traits in an all-powerful leader. Pliny the Elder, a rough contemporary of Tiberius's[note 3], called him tristissimus hominum, “the gloomiest of men.”[3]

Second, the office of Emperor was still fairly ill-defined, and it was unclear what position Tiberius was actually inheriting. Unlike most subsequent emperors, Tiberius seems to have wanted less power than was conferred on him and expected the Senate to take an active role in governing.[4] The Senate, whose members had perhaps grown comfortable serving in a rubber-stamp institution, disagreed. For his part, Tiberius developed a contempt for the Senate, calling them "men fit to be slaves."[5]

Third, his reign was dogged by succession crises. Tiberius took office when he was already 55, and few people expected him to rule as long as he did: this situation repeatedly led to trouble, as different factions vied to have their man-made heir. In 19 AD, five years into his reign, Tiberius's heir apparent Germanicus, his nephew and adopted son, fell ill and died. Worse still, Germanicus had from his deathbed accused Gnaeus Calpernius Piso, governor of Syria and a longtime political ally of Tiberius's, of poisoning him[6]. The charge against Piso--who killed himself before his trial was concluded[7][8]--combined with the contrast between Germanicus's charisma versus Tiberius's charmlessness, gave rise to rumors that Tiberius had ordered Germanicus's assassination. Germanicus's widow Agrippina believed the rumors, and a bitter feud developed between her and Tiberius, in which she rallied her husband's former supporters around herself; the feud would last until Tiberius had her banished for treason a decade later[9]. Tiberius's decision to make his biological son Drusus his heir probably heightened the suspicion. Then, in 23 AD, Drusus too died mysteriously, after which Tiberius had had enough of politics, and in AD 26, now in his late sixties, he just... went away, without deigning to name a clear successor. Tiberius largely left rule of the Empire in the hands of his close friend Sejanus, the commander of the Praetorian Guard, while he romped on his own personal island resort at Capri. Sejanus then began plotting to betray the emperor and usurp the throne. Details are sketchy, but we do know that the plot failed, and Sejanus was executed. Having just executed his close friend and advisor, Tiberius reportedly became paranoid for the last few years of his reign and held many show trials that led to the executions of many powerful Roman citizens. Tiberius died at the tender age of 78, six years after the execution of Sejanus. In his will, he named his grand-nephew Caligula and his teenage grandson Gemellus as his joint-heirs.[10]

It must be remembered, however, that few written accounts survive the period. Notably, the senator and historian Tacitus who lived a generation after Tiberius composed a history of his reign and those of his two successors and the turmoil following their reigns. Being a senator under Caligula and Nero who did away with much of the remaining window dressing of Augustus about the emperor merely being the "first citizen", and instead behaving as the monarchs/dictators they were in practice without any of the flattering of the senatorial class, Tacitus had a particular disdain of emperors both as persons and as an office. In a similar vein, Suetonius, a bureaucrat and historian who wrote after Tacitus, focused mainly on the sensational, hedonistic stuff, contrasting Tiberius with his ideal of an emperor, Augustus.[note 4]

Caligula (37–41)[edit]

Cruel, perverted, egotistical, and insane. Had his co-heir Gemellus shunted out of political power, and then executed for good measure, Reported to have had relations with all of his sisters, with Julia Drusilla being the one he actually married. Would beat people with more hair than him, which was pretty much everyone without alopecia universalis. Thought he was a god. He is particularly famous for making his horse Incitatus a senator, or at least threatening to do so (which may have been less an act of mind-melting insanity and more of a giant middle finger to the senate, whose members thought rather highly of themselves). However, most claims about his craziness were only recorded by Suetonius and Cassius Dio decades later, and so might be exaggerations of a genuine fondness for horses.[11] It is said that he led an army to the English channel, stopping at the coast to declare war on the sea-god Neptune, and made his soldiers collect seashells as war booty. The last straw came when he ordered a golden statue of himself to be constructed in the Jerusalem Temple.[12] He was finally assassinated by his own bodyguards.

Claudius (41–54)[edit]

He was considered a halfwit because he limped and stammered (ah, those tolerant Romans), which was probably why Caligula didn't have him killed, but Claudius became emperor anyway. Claimed to exaggerate his disability to survive Caligula's reign. He was a prolific writer and an amateur historian, although very little of his writing (and none of his scholarly work) survives to the present. In his surviving letters, edicts and speeches, he comes across as tough but fair[13]. Mostly. Responsible for the construction of the port at Ostia. Picked up where Caligula left off and actually conquered Britain. Had many wives, but only had one of them executed. He was probably poisoned by his last empress so that her son Nero could take over.

Nero (54–68)[edit]

Caligula's nephew, also cruel, perverted, egotistical, and insane; in short, a chip off the old block. Participated in the Olympic Games, and won the chariot race even though he was the only competitor to fall off his chariot. Supposedly played the lyre while Rome burned.[note 5] He is accused of blaming Christians for the fire and persecuting them afterward, although there is little or no actual evidence that he did so.[14] Tacitus mentions that Nero persecuted the "Christians" or "Chrestians" for the fire as a scapegoat to avoid blame (because even the earliest surviving text dates from the 11th century, it is unclear what Tacitus wrote and whether he meant Christians or some other group).[15] Suetonius says Nero punished the followers of Chrestus because they were "given to a new and mischievous superstition", while also not connecting them to the fire, and again not being clear that he referred to actual followers of Jesus Christ or some other sect.[16]

Nero is claimed to have fed Christians to lions, which is unlikely, as the Colosseum wasn't even built yet; beheading would have been a more usual fate, as with St Paul of Tarsus, although low-ranking criminals were fed to animals in the 2nd century CE.[17] It is also said that he used crucified Christians covered in pitch as lamps in his garden (after setting them on fire), which is colorful but possibly not accurate. The debate as to what role Nero did play in the persecution of early Christians is pretty big. Still, given a lack of contemporary sources from the period of Nero's reign, and a tendency for Christians to claim persecution at all possible occasions, it's... problematic, to say the least. Most accounts of Nero's persecutions date from the 4th-century histories of two Christian writers, Lactantius and Eusebius, so they are neither neutral nor eyewitnesses.[17] But, given some of his other actions, such as killing his wife so he could marry another woman whom he may have later beaten to death while she was pregnant with his kid, it's not hard to guess he was capable of some severe brutality, making it easy to imagine him actually doing the stuff he is often accused of.

One act of Nero's that was both mindbendingly stupid and well-documented was his taxation policy towards Greece, when, after a pleasant trip to it during which he was received (one presumes) with great flattery and pomp, he decided to repay the Greeks' hospitality by excusing them-- as in, the entire country--from paying imperial taxes.[18] This would be a dangerous, dumb move even for an emperor as fiscally responsible as Tiberius. For a spendthrift like Nero, it was political suicide. The catastrophic Roman fire that followed this edict, and the vast cost of rebuilding the city, necessitated severe increases in taxation everywhere else in the empire, which hurt Nero's popularity everywhere but Greece; a dangerous situation, since Nero's capital was not in Greece.

He also had his mother stabbed after a bizarre attempt at killing her involving a death boat. Literally, a death boat. He had a henchman build "a collapsible boat" which would then be shipwrecked.[19] Failed. While Nero was by no means a good ruler, we have to acknowledge that he did manage to piss off the two groups of people whose written works are most likely to have survived to the present day: Christians and the old senatorial elite. It is entirely possible that other groups had a more favorable view of him but either never got around to writing the biography of him they were planning, or they did write something, and it was simply lost over time. One indication of Nero's popularity outside the senatorial/Christian groups of history writers is that several impostors claiming to be Nero popped up after his death. If Nero was the universally reviled monster of our written sources, it's hard to see why anyone would want to impersonate him or how doing so would help them gain control of the Roman Empire. But there is a possible reason, as he often made laws that pleased the lower classes, which is probably why he was so popular with them (and unpopular with the upper classes). It's very possible and likely that this was what he wanted, and he was criticized for being obsessed with it. It seems he started off okay, but the latter part of his rule is where he started to go a bit....downhill. And while he actually did do a lot to help Rome after it burned, his efforts significantly drained the State's budget. The projects were so massive that Rome didn't have the money needed. So, Nero devalued Roman currency for the first time in the Empire's history. Oh, and remember how he played a big part in rebuilding Rome after the fire? He had a 30-meter-tall statue of himself, the Colossus of Nero, constructed out of bronze. Most historians agree that the name for the Colosseum was derived from it. So, while Nero was popular with the lower classes, the Senate disliked him for being very excessive.

After the Julio-Claudians[edit]

After Nero, there were a whole load of minor emperors[note 6], some reigning for mere months. Vespasian (69-79) imposed a urine tax[note 7], which was indeed taking the piss.[note 8] It must be stated, however, that this made sense; urine from public latrines was collected because, before the invention of soap, the only way to wash clothes was with ammonia, which meant that they had to find a source of urea to turn into ammonia so... yeah. The Romans used urine to wash their clothes. He and his son Titus also presided over the construction of the Colosseum and the destruction of the Second Temple of Jerusalem, causing the Jewish exile, the ramifications of which are still a significant issue, nearly 2,000 years later. Titus (79-81) has one of the best records of any Roman emperor among ancient historians, noted for his generosity. Major occurrences during his brief reign include the completion of the Colosseum, the eruption of Mount Vesuvius and a second fire of Rome that destroyed several important buildings including the original Pantheon, for which he took large amounts of money from the imperial treasury to personally compensate victims of the disasters. He is condemned in Jewish memory as "Titus the Wicked" for his earlier role in the destruction the Second Temple. Domitian (81-96) was a cruel paranoiac who ordered mass arrests of anyone suspected of treason and liked to stab flies with his pen.

The Five Good Emperors[edit]

After all those others, the Romans were entitled to a big break. And they got it in the form of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty, named "The Five Good Emperors" by Niccolo Machiavelli who surprisingly disliked tyrants.

- Nerva (96–98) Decriminalised treason and released political prisoners arrested under Domitian.

- Trajan (98–117) extended the empire to its largest.[note 9]

- Hadrian (117–138) was famous for his wall

across Britain.

across Britain. - Antoninus Pius (138–163) brought about legal reform, banned the execution of children under the age of fourteen, and introduced various human rights based policies to Rome.

- Marcus Aurelius (161–180) wrote Meditations, regarded as a classic work on Stoicism

.[20]

.[20]

Commodus[edit]

Then things went downhill again. Commodus (177-192) was co-emperor with his father for three years; he's the one in Gladiator although, unlike in the film, he was never in danger of not being the heir, nor did he murder his father. He believed he was Hercules' reincarnation and liked to dress up as him and sprinkle gold dust in his hair. Fought in the Colosseum against Russell Crowe trained gladiators and won, though making them fight with wooden swords while he used metal ones may have helped. Had people fed to the lions for booing him and had a servant burned to death for making his bath too cold. Renamed Rome, the Empire, the entire Praetorian Guard, and various streets after himself, which made life really confusing.[note 10] Devalued Roman coinage while raising taxes. Mass poverty raged throughout Rome as a result. He was finally strangled to death in his bath by his wrestling partner, ironically named Narcissus[note 11]. Still, during his reign, he's credited with single-handedly ending the Pax Romana (or Pax Commodiana as it was known during his time). Years later and the only thing named after him is the commode. The Romans had vicious emperors (Caligula, Nero) and idiot emperors (allegedly Claudius) but until Commodus came along, they'd never had a vicious idiot before.

Several Severans, a crisis, and Diocles[edit]

Commodus's murder started the "Year of Five Emperors" — if you guessed four of these emperors were murdered, then you've been paying attention. In the end, a general named Septimius Severus took control. He is generally considered a good ruler and an excellent general, as his achievements included defeating Rome's old enemy, Parthian Persia, in a war for control over Mesopotamia. Under Severus, the Empire reached its largest territorial extent. Ultimately, however, his reign was based on an expanded and loyal (read: well-bribed) army, which he achieved by debasing Rome's currency twice. This would become important later. [21]. When he died, his sons took control, thus beginning the "Severan Dynasty".

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus, known after his death as Elagabalus (or Heliogabalus) after a Syrian sun god he served as high priest, was a member of this dynasty. He became emperor at the age of fourteen, mostly thanks to his wealthy grandmother Julia Maesa. His reign was an unmitigated disaster-he neglected his duties as emperor to evangelize Elagabal. While this god was popular in the east, many customs associated with his worship were seen as barbaric by the romans. Elagabalus was finally assassinated at the age of eighteen by (who else?) the Praetorians, and vilified intensely after his death. Like Caligula and Nero before him, his reign is a nice source of depraved anecdotes frustratingly entrenched in popular memory even though most serious historians place little weight on them.

Elagabalus's successor, his popular cousin Alexander, had a surprisingly pleasant reign, but in typical Roman fashion, was murdered — his soldiers attacked him for trying to negotiate with some German tribes rather than start a new war against them. His death ushered in a chaotic period known as the "Crisis of the Third Century". The Crisis was roughly fifty years of civil war and slaughtered emperors and emperor-wannabes. Huge chunks of the empire broke away and became their own independent empires, while German tribes invaded and ran wild. During this period, the emperors were usually generals with little political experience, frequently commoners who had risen through the ranks. Later in the Crisis, some of these general-emperors were able to retake the breakaway empires, slowly piecing the empire back together, and then a guy named Diocles took power. Renaming himself Diocletian, he brought an end to the old ways — no longer was the Roman Emperor technically answerable to the Senate; he had officially become a despot with absolute power. The old Principate (from the Latin term Princeps Civitatis or "First Citizen") gave way to the Dominate (from the word for "lord"). Diocletian also experimented with splitting up the empire into smaller, more manageable chunks but with himself still ultimately in charge. Eventually, Diocletian got old and sick and became the first emperor to retire[note 12] — that's right! Not all emperors were killed!

And the rest...[edit]

A succession of minor figures follows until we get to Constantine I (306-337), called Constantine the Great by many. He legalized Christianity, convened the Council of Nicaea, and had his wife and son executed, as he thought they were being sexually active with each other. After him came more minor emperors as well as Julian[note 13], who tried to push Rome back to paganism (care to guess how his efforts were rewarded?). Theodosius I (379-395) made Christianity the state religion. After Theodosius, the empire violently and permanently (having already been sectioned off before Constantine) split in half, with the West soon falling to repeated invasions while the East continued on.

There were a few bright spots. In the sixth century A.D., Eastern Emperor Justinian tried to reconquer the Western Empire but, aside from retaking Italy[note 14] and parts of North Africa, mostly failed. He rewrote Roman laws, which provided the groundwork for most of modern Europe's laws. He also reigned through one of the worst plagues in human history, as well as massive riots caused by unruly sports fans. His wife and co-regnant, Theodora, was one of the more interesting figures from antiquity: she was a former "actress" at a time when theatres were basically strip clubs, twenty years Justinian's junior, and exceptionally politically savvy. Justinian made her his co-ruler and assigned her word legal weight equal to his own, thus giving the empire two de facto sovereigns.[22] Heraclius switched the official language from Latin to Greek, since almost everyone was speaking Greek anyway, and he finally defeated Rome's old enemy Persia — just in time for followers of the brand-new religion called Islam to come along and conquer the Middle East. The Eastern Empire then more or less limped along[note 15] (the old fads of civil wars and murdered emperors never went out of style) until 1453 when it fell to the Ottoman Turks, finally bringing an end to the Roman Empire.

External links[edit]

- De Imperatoribus Romanis: An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Rulers and Their Families -- An excellent resource on the history of the Roman emperors.

Notes[edit]

- ↑ A complicating factor is that failing to suck up to the senatorial class, who wrote our extant histories of the era, could give you a particularly nasty epitaph. Nero is at least partly a case of this; worse still, he mingled with the ordinary citizens, the cad. Despite his bad rep, however, there were still impersonators who claimed to be him after his death, and who would try to get into power by claiming to be a universally hated tyrant?

- ↑ Bear in mind that, to the Roman poor, citizenship was often the only thing distinguishing them from Italians. The Romans fought a war

about this, so it was a pretty big deal

about this, so it was a pretty big deal

- ↑ Pliny the Elder was in his late teens when Tiberius died, which for Roman history makes him a virtual primary source.

- ↑ A pretty common theme in Roman historiography, btw.

- ↑ Not the fiddle, as it wasn't invented until the 10th century. See the Wikipedia article on fiddle.

- ↑ The year 69 was known as "the year of four emperors" in Rome

- ↑ Famously claiming "pecunia non olet" — money does not stink — upon doing so

- ↑ We're sorry, all right?!

- ↑ Or is often credited as such; in truth, it appears that honor goes to Septimius Severus, but Trajan's expansions were certainly more sustainable.

- ↑ Shows you where Turkmenbashi got his ideas, though.

- ↑ The guy who renamed his Empire after himself was killed by a guy called Narcissus. Geddit?

- ↑ In Spalatum (Split), modern-day Croatia of all places

- ↑ Often called Julian Apostate by Christian apologists

- ↑ And completely ravaging the peninsula through a long war against the Ostrogoths who were a slightly different type of Christian from himself - proving once and for all that Christianity is a religion of peace

- ↑ In surprising strength until the early 13th century when it was sacked in a crusade by a slightly different branch of Christianity — proving once and for all... you know the drill.

References[edit]

- ↑ https://www.romae-vitam.com/roman-principate.html

- ↑ http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Proscriptio.html

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural Histories XXVIII.5.23; Capes, p. 71

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals III.35, III.53, III.54

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals III.65

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals II.71

- ↑ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 52

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals III.15

- ↑ De Imperatoribus Romanis | Agrippina the Elder https://www.roman-emperors.org/aggiei.htm | Agrippina the Elder. Retrieved 2018-08-31.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.1

- ↑ Did Caligula really make his horse a consul?, Elizabeth Nix, History.com

- ↑ Caligula (AD 12 - 41) BBC History

- ↑ Claudius, Letter of the Emperor Claudius to the Alexandrians: An imperial missive sent in response to sectarian violence between Alexandria's Greek and Jewish communities that had raged for most of Caligula's reign.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Tacitus on Christ.

- ↑ See the Wikipedia article on Suetonius on Christians.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Mythbusting Ancient Rome – throwing Christians to the lions, The Conversation, Nov 21, 2016

- ↑ Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 8794, quoted in Parkin & Pomeroy, Roman Social History: A Sourcebook, Social Classes

- ↑ Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars, The Life of Nero, 34

- ↑ Practical Lessons in Stoic Philosophy from Marcus Aurelius: an overview of Marcus Aurelius, Stoicism, and Meditations.

- ↑ https://dailyhistory.org/How_did_Emperor_Septimius_Severus_change_the_Roman_Empire?

- ↑ http://www.roman-emperors.org/dora.htm

Categories: [Anti-Christian bigots] [Antisemites] [Racists] [Roman history] [Romans] [Religious leaders] [Monarchs] [Dictators]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 12/27/2025 22:15:35 | 26 views

☰ Source: https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Roman_emperor | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

.jpg/250px-thumbnail.jpg)

.jpg/250px-MBALyon2018_-_Expo_Claude_-_Statue_Caligula_(detail).jpg)

KSF

KSF