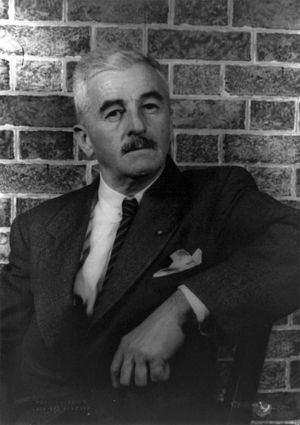

William Faulkner

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia William Cuthbert Faulkner (September 25, 1897 - July 6, 1962) was a Nobel and Pulitzer prize winning American author. He was a lifelong resident of Mississippi, and its only Nobel laureate, winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949. He was reportedly recommended to the committee by a Swedish journalist who translated American novels. Prior to the award, Faulkner's works were mostly out-of-print. Though portrayed as liberal, he penned the conservative Requiem for a Nun (1951) about a woman overcoming her troubled past: “The past is never dead. It's not even past.”[1]

Faulkner wrote more per day than most: 3,000 to 10,000 words per day, compared with the 500 words per day written by Ernest Hemingway.[2]

A favorite of liberals in the second half of the 20th century, and mandatory reading for high school students, Faulkner's frequent reliance on the N-word in many of his novels has marginalized him today. Faulkner also made public statements that would be considered racially offensive now. He lied throughout his life about war injuries he never had. Yet in some non-racial ways Faulkner was quite conservative.

Faulkner did not graduate from high school or college, and was mostly self-taught or homeschooled. Both of his parents were from wealthy families which had lost everything due to the Civil War.

Faulkner is most famous for writing The Sound and the Fury (1929), As I Lay Dying (1930),[3] and Absalom, Absalom! (1936).[4][5][6][7]

Faulkner wrote about the fall of Southern aristocracy. Difficult to follow, his works are creative and explore psychological aspects of his characters. The names for his fictional location (Yoknapatawpha County) and individuals are often hard to pronounce. Liberals like Faulkner for his mockery of southern whites, which Faulkner does in the form of stream-of-consciousness in As I Lay Dying.

The Sound and the Fury is considered Faulkner's finest work, which consists of four segments narrating a single day each, three in 1928 and one in 1910. They are written as stream-of-consciousness, one of which was a mentally impaired person. Absalom, Absalom!, another of Faulkner's novels, is considered by liberals to be the greatest southern novel ever written, but it frequently uses the N-word, even gratuitously by characters depicted as enlightened. Conservatives would consider Gone with the Wind to be a finer southern novel. In Faulkner's characteristically bizarre style, his novel Absalom, Absalom! contains the longest sentence in American literature: 1,228 words.[8] (Other very long sentences are in Jonathan Coe’s The Rotter’s Club (a 13,955 word sentence) and James Joyce's Ulysses (a 4,391 word sentence).[9]

As I Lay Dying relies on profanity, includes references to an abortion, and questions the existence of God. It was initially banned for high school students by a Kentucky school board in 1986 for those reasons.[10] Under pressure from the ACLU, the Board voted 4-1 to reverse the ban.

Faulkner eventually married his childhood sweetheart in 1929, after she divorced the man she had married a decade earlier, under pressure from her family.[11]

Family[edit]

Faulkner's first child, to whom he dedicated (along with his wife) his first published collection of essays, was a baby girl named "Alabama" born two months prematurely. She tragically died ten days later while Faulkner was frantically attempting to obtain an incubator to help her survive.[12]

Conservatism[edit]

A thoughtful essay by Carl Rollyson explains many conservative themes by Faulkner, who "revealed his conservative vision in novels like Absalom, Absalom! (1936) and Requiem for a Nun (1951) espousing the eternal verities of civilization," and "[l]ike Russell Kirk, Faulkner believed in the principles of precedent and prescription."[13]

Movies[edit]

Intruder in the Dust (1949) is a film adaptation of the novel by Faulkner published the prior year, about a black man accused of murdering a white man in a small Mississippi town. It was filmed in Faulkner's town of Oxford, Mississippi.[14]

Quotations[edit]

| “ | The past is never dead. It’s not even past.[15] | ” |

References[edit]

- ↑ https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/12124-the-past-is-never-dead-it-s-not-even-past

- ↑ https://writingcooperative.com/10-legendary-writers-their-daily-word-counts-692c56cb97a5

- ↑ As I Lay Dying contains 56,903 words and relatively high use of the passive voice. [1]

- ↑ http://www.mcsr.olemiss.edu/~egjbp/faulkner/faulkner.html

- ↑ http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1949/faulkner-bio.html

- ↑ http://almaz.com/nobel/literature/1949a.html

- ↑ http://www.booksfactory.com/writers/faulkner.htm

- ↑ http://www.openculture.com/2019/03/when-william-faulkner-set-the-world-record-for-writing-the-longest-sentence-in-literature.html

- ↑ https://thejohnfox.com/long-sentences/

- ↑ https://www.apnews.com/b8f43ca4132af2b0d54b74d757b268b6

- ↑ https://www.notablebiographies.com/Du-Fi/Faulkner-William.html

- ↑ https://www.al.com/entertainment/2015/09/the_tragic_tale_of_william_fau.html

- ↑ https://theimaginativeconservative.org/2021/09/old-rowan-oak-conservatism-william-faulkner.html

- ↑ https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/intruder_in_the_dust_1949

- ↑ From Requiem for a Nun (1951).

External links[edit]

| ||||||||||||||

Categories: [Novelists] [Nobel Laureates in Literature] [Writing] [People who were Educated at Home] [Liberals]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/18/2023 08:20:28 | 6 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/William_Faulkner | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF