Political Integration Of India

From Nwe

From Nwe The political integration of India established a united nation for the first time in centuries from a plethora of princely states, colonial provinces and possessions. Despite partition, a new India united peoples of various geographic, economic, ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. The process began in 1947, with the unification of 565 princely states through a critical series of political campaigns, sensitive diplomacy and military conflicts. India transformed after independence through political upheaval and ethnic discontent, and continues to evolve as a federal republic natural to its diversity. Sensitive religious conflicts between Hindus and Muslims, diverse ethnic populations, as well as by geo-political rivalry and military conflicts with Pakistan and China define the process.

When the Indian independence movement succeeded in ending the British Raj on August 15 1947, India's leaders faced the prospect of inheriting a nation fragmented between medieval-era kingdoms and provinces organized by colonial powers. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, one of India's most respected freedom fighters, as the new Minister of Home Affairs emerged as the man responsible for employing political negotiations backed with the option (and the use) of military force to ensure the primacy of the Central government and of the Constitution then being drafted.

India's constitution pronounced it a Union of States, exemplifying a federal system with a strong central government. Over the course of the two decades following Independence the Government of India forcefully acquired the Indian possessions of France and Portugal. But the trend changed as popular movements arose for the recognition of regional languages, and attention for the special issues of diverse regions. A backlash ensued against centralization — the lack of attention and respect for regional issues resulted in cultural alienation and violent separatism. The central government attempted to balance the use of force on separatist extremists with the creation of new States to reduce the pressures on the Indian State. The map has been redrawn, as the nature of the federation transforms. Today, the Republic of India stands as a Union of twenty eight states and seven union territories.

British India

British colonization of the Indian subcontinent began in the early 18th century. By the mid-19th century, most of the subcontinent fell under British rule. With the arrival of Lord Mountbatten (the former Lord Louis Mountbatten later created Viscount Mountbatten of Burma, then promoted to Earl) as the Viceroy of India in early 1947, the British government under Prime Minister Clement Attlee clearly proclaimed the imminent independence of India. Elections for provincial legislatures and the Constituent Assembly of India had been held in 1946. India's top political parties, the Indian National Congress and the All India Muslim League both began negotiating the impending transfer of power as well as the make-up of the new Indian government. In June 1947, the Congress and the League agreed to the partition of India into two independent British Commonwealth dominions: India and Pakistan. Burma, separated from British India in 1937, became independent along with Ceylon (never a part of British India) in 1948.

Without the princely states, the Dominion of India would comprise the provinces of Bombay Presidency, Madras Presidency, the United Provinces of Agra and Oudh, the Central Provinces and Berar, Assam, Orissa, Bihar, and the chief commissioners' provinces of Coorg, Ajmer-Merwara, Panth-Piploda, and Delhi. The North West Frontier Province, Sind, and the chief commissioners' province of Baluchistan would go to Pakistan. The provinces of Bengal and Punjab had been partitioned in 1946, with India retaining West Bengal and East Punjab, the Hindu-majority portions of the larger provinces. West Punjab and East Bengal, heavily Muslim, went to Pakistan. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands and the Lakshadweep Islands would be turned over to the control of India.

Princely states

Between 570 and 600 princely states enjoyed special recognition by, and relationship, with the British Raj. The British government announced in the Indian Independence Act 1947 that with the transfer of power on 15 August 1947, all of those states would be freed of their obligations to the British Empire, leaving them free to join either India or Pakistan, or to choose to become independent. The kingdom of Nepal, an independent treaty ally, became a fully sovereign nation. The kingdom of Bhutan dissolved its protectorate relationship similarly but, via treaty in 1949, kept India as the guarantor of its security. The kingdom of Sikkim became a protectorate of India. Apart from a few geographically unalienable from Pakistan, approximately 565 princely states linked to India, the largest nation.

The largest of them included Hyderabad and Kashmir, while 222 states existed in the Kathiawar peninsula alone. The states comprised more than half of the territory of India and a large proportion of its population. Experts maintained that without a single federal structure, India would be susceptible to political, military and social conflicts. The British had taken control of India piecemeal and over the course of a century; most of the states had signed different treaties at different times with the British East India Company and the British Crown, giving the British Raj varying degrees of control over foreign, inter-state relations and defense. Indian monarchs accepted the suzerainty of Britain in India, paid tribute and allowed British authorities to collect taxes and appropriate finances, and in many cases, manage the affairs of governance via the Raj's Political Department. The princes held representation in the Imperial Legislative Council and the Chamber of Princes, and under law enjoyed relationships described as that of allies, rather than subordinates. Thus the princes maintained a channel of influence with the British Raj.

Process of accession

The states of Gwalior, Bikaner, Patiala and Baroda joined India first on April 28, 1947. Others felt wary, distrusting a democratic government led by revolutionaries of uncertain, and possibly radical views, and fearful of losing their influence as rulers. Travancore and Hyderabad announced their desire for independence while the Nawab of Bhopal, Hamidullah Khan, expressed his desire to either negotiate with Pakistan or seek independence. The Nawab exerted a powerful influence on a number of princes, as he had prestige as the former chancellor of the Chamber of Princes. In addition, Jodhpur, Indore and Jaisalmer conducted a dialogue with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the slated Governor-General of Pakistan, to discuss terms for a possible accession to it. While that surprised many in both India and Pakistan, neither party could ultimately ignore the fact that those kingdoms held Hindu majorities, which rendered their membership in overwhelmingly Muslim Pakistan untenable.

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel served as the Minister for Home and States Affairs, receiving the explicit responsibility of welding a united and strategically secure India in time for the transfer of power. The Congress Party, as well as Lord Mountbatten and senior British officials, considered Patel the best man for the task. Mahatma Gandhi had said to Patel "the problem of the States is so difficult that you alone can solve it".[1]Recognized by the Princes and parliamentarians alike as a man of integrity, many also considered Patel gifted with the practical acumen and resolve needed to accomplish a monumental task. Patel asked V. P. Menon, a senior civil servant, with whom he had worked over the partition of India, to become the Secretary in charge of the Home and States Ministry, as then constituted. Patel's admirers would later call him the Iron Man of India[2] for his decisive actions at this time.

Instrument of accession

Sardar Patel and V.P. Menon devised a formula to propose to the monarchs. The Instrument of Accession became the official treaty scheduled for signing between the Government of India or the Government of Pakistan and the accession candidates. According to the basic tenets of the treaty, the Government of India would control only foreign affairs, defense and communications, leaving all internal issues to the states to administer. On July 5 1947, the Government of India released the official policy, and stating:

{{cquote|We ask no more of the States than accession on these three subjects in which the common interests of the country are involved. In other matters we would scrupulously respect their autonomous existence. This country… is the proud heritage of the people who inhabit it. It is an accident that some live in the States and some in British India… None can segregate us into segments… I suggest that it is better therefore for us to make laws sitting together as friends than to make treaties as aliens. I invite my friends the rulers of States and their people to the councils of the Constituent Assembly in this spirit of friendliness… Congressmen are no enemies of the princely order.[3]

Considering that the princes had to sign away the sovereignty of states where their families had reigned for centuries, and that they believed that India's security would be jeopardized if even one state refused to sign on, Patel and Menon held the opinion that Instrument represented the best deal they could offer the princes. While negotiating with the states, Patel and Menon also guaranteed that monarchs who signed on willingly would be retained as constitutional heads of state, although they would be 'encouraged' to hand their power over to an elected government. Once states signed the Instrument of Accession, they received the right to have representation in the Constituent Assembly of India, thus becoming an active participant in framing the new Constitution.

Patel's diplomacy

On May 6, 1947, Patel began lobbying the princes, attempting to make them receptive towards dialogue with the future Government and trying to forestall potential conflicts. Patel used social meetings and unofficial surroundings to engage most monarchs, inviting them to lunch and tea at his home in Delhi. At those meetings, Patel would claim that there was no inherent conflict between the Congress and the princely order. Nonetheless, he stressed that Congress expected the princes to accede to India in good faith before the deadline, August 15, 1947. Patel also listened to the monarchs’ opinions, seeking to address their two chief concerns:

- The princes feared that the Congress would be hostile to the princely order, attacking their property and, indeed, their civil liberties. Their concern arose from the large proportion of Congress pledging socialist inclination. Patel, who disavowed allegiance to the socialist faction, promised personally that the Congress would respect the Indian princes, their political power, and their property, only asking concessions when 'necessary' for the stability and unity of India.

- Patel assured the monarchs of the states that after acceding to India, they would be allowed to retain their property and estates. Further, they would be fully eligible to run for public office.

- For the loss of income (from revenue), the monarchs would be compensated with a privy purse.

- The princes also expressed worries that the guarantees offered by Patel while the British still ruled would be scrapped after August 15. Patel thus had to promise to include the guarantees of privy purses and limited central powers in the as yet unframed Constitution.

Patel invoked the patriotism of India's monarchs, asking them to join in the freedom of their nation and act as responsible rulers who cared about the future of their people. Patel frequently dispatched V. P. Menon frequently to hold talks with the ministers and monarchs. Menon would work each day with Patel, calling him twice, including a final status report in the night. Menon stood as Patel's closest advisor and aide on the diplomacy and tactics, and handling of potential conflicts, as well as his link with British officials. Patel also enlisted Lord Mountbatten, whom most of the princes trusted and a personal friend of many, especially the Nawab of Bhopal, Hamidullah Khan. Mountbatten also constituted a credible figure because Jawaharlal Nehru and Patel had asked him to become the first Governor General of the Dominion of India. In a July, 1947 gathering of rulers, Mountbatten laid out his argument:

| “ | ...The subcontinent of India acted as an economic entity. That link is now to be broken. If nothing can be put in its place, only chaos can result and that chaos, I submit, will hurt the states first. The States are theoretically free to link their future with whichever Dominion they may care. But may I point out that there are certain geographical compulsions which cannot be evaded?[4] | ” |

Mountbatten stressed that he would act as the trustee of the princes' commitment, as he would be serving as India's head of state well into 1948. Mountbatten engaged in a personal dialogue with the Nawab of Bhopal. He asked through a confidential letter to him, that he sign the instrument of accession, which Mountbatten would keep locked up in his safe to be handed to the States Department on August 15 only if the Nawab still agreed. He could freely change his mind. The Nawab agreed, keeping the deal intact.[5]

Accession of the states

From June to August 15 1947, 562 of the 565 India-linked states signed the instrument of accession. Despite dramatic political exchanges, Travancore, Jodhpur and Indore signed on time. Patel willingly took on other Indian leaders for the sake of accomplishing the job. The privy purse pledge, offensive to many socialists, earned Prime Minister Nehru's complaint, arguing that Patel by-passed the Cabinet to make the pledge to the Princes. Patel, describing the pledge as an essential guarantee of the Government's intentions, won approval for incorporation into the Constitution. (In 1971, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi's Congress Party repealed the clause through a constitutional amendment.[6]) Patel defended their right to retain property and contest elections for public office, and today, especially in states like Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, descendants of the formerly royal families play an important role in politics.

During the strenuous process of integration, three major conflicts arose that posed a major threat to the Union:

Junagadh

Junagadh, a state on the southwestern end of Gujarat, consisted of the principalities of Manavadar, Mangrol and Babriawad. The Arabian Sea stood between it and Pakistan, and over 80% of its population professed Hinduism. Possibly on the advice of his Dewan, Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, prominent in the Muslim League, the Nawab of Junagadh Mahabhat Khan acceded to Pakistan. They announced the accession on August 15 1947, when Pakistan had come into being. When Pakistan confirmed the acceptance of the accession in September, the Government of India expressed outraged that Muhammad Ali Jinnah would accept the accession of Junagadh despite his argument that Hindus and Muslims could not live as one nation.[7] Patel believed that if Junagadh joined Pakistan, the communal tension already simmering in Gujarat would exacerbate.

Patel gave Pakistan time to void the accession and hold a plebiscite in Junagadh. Samaldas Gandhi formed a democratic government-in-exile, the Aarzi Hukumat (in Urdu:Aarzi: Temporary, Hukumat: Government) of the people of Junagadh. Eventually, Patel ordered the forcible annexation of Junagadh's three principalities. Junagadh's court, facing financial collapse and no possibility of resisting Indian forces, first invited the Aarzi Hukumat, and later the Government of India to accept the reins. A plebiscite convened in December, with approximately 99% of the people choosing India over Pakistan.[8]

Kashmir

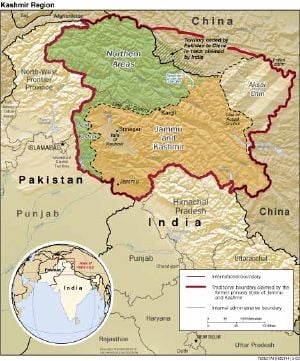

Maharaja Hari Singh, a Hindu, equally hesitant about acceding to either India &mdash, felt his mostly Muslim subjects would not like joining a Hindu-majority nation — or Pakistan — an eventuality which he would personally prefer to avoid. He personally believed that Kashmir could exercise its right to stay independent; a belief Sheikh Abdullah, the leader of Kashmir's largest political party, the National Conference backed. Pakistan coveted the Himalayan kingdom, while Indian leaders including Gandhi and Nehru, hoped that the kingdom would join India. Hari Singh signed a Standstill Agreement (preserving status quo) with Pakistan, but still withheld his decision by August 15.

Pakistan, concerned about the lack of movement on the front, attempted to force the issue by permitting the incursions of tribals from the North-West Frontier, followed in September 1947 by regular forces. India offered military assistance to the Kashmiri Government, which lacked an organized military; such assistance came on the condition of the Maharaja signing the Instrument of Accession, which he then did.[9] By that time, the raiders closed in on the capital of Srinagar. Indian troops secured Jammu, Srinagar and the valley itself during the First Kashmir War, but the intense fighting flagged with the onset of winter, which made much of the state impassable. Prime Minister Nehru, recognizing the degree of international attention brought to bear on the dispute, declared a ceasefire and sought U.N. arbitration with the promise of a plebiscite. Patel had argued against both, describing Kashmir as a bilateral dispute and its accession as justified by international law. Patel had feared that the U.N.'s involvement would stall the process and allow Pakistan to reinforce its presence in Kashmir. Additionally, the outcome of a plebiscite remained highly uncertain. In 1957, Kashmir officially integrated into the Union, but with special provisions made for it in the Constitution's Article 370. The northwestern portion remaining under control of the Pakistan army remains today as Pakistan-administered Kashmir. In 1962, China occupied Aksai Chin, the northeastern region bordering Ladakh.

Hyderabad

Hyderabad constituted a state that stretched over 82,000 square miles (over 212,000 square kilometres) in the center of India with a population of 16 million, 85% of whom declared themselves Hindus. Nizam Usman Ali Khan, the ruler, had always enjoyed a special relationship with the British Raj. When the British ruled out dominion status, the Nizam set his mind upon independence, under the influence of Muslim radical Qasim Razvi. Without Hyderabad, a large gap would exist in the centre of the united nation envisioned by Indian nationalists and the Indian public. Patel believed that Hyderabad looked to Pakistan for support, and could pose a constant threat to India's security in the future. Patel argued Hyderabad essential for India's unity, but he agreed with Lord Mountbatten to refrain from using force. Hyderabad signed a Standstill Agreement — an agreement made with no other princely state without an explicit assurance of eventual accession. Patel required Hyderabad promise to refrain from joining Pakistan. Mountbatten and India's agent K.M. Munshi engaged the Nizam's envoys into negotiations. When the negotiations failed to achieve an agreement, the Nizam alleged that India had created a blockade. India, on the other hand, charged that Hyderabad received arms from Pakistan, and that the Nizam allowed Razvi's Razakar militants to intimidate Hindus and attack villages in India.

Lord Mountbatten crafted a proposal called the Heads of Agreement, which called for the disbandment of the Razakars and restriction of the Hyderabad army, for the Nizam to hold a plebiscite and elections for a constituent assembly, and for eventual accession. While India would control Hyderabad's foreign affairs, the deal allowed Hyderabad to set up a parallel government and delay accession. Hyderabad's envoys assured Mountbatten that the Nizam would sign the agreement, and he lobbied Patel hard to sign for India. Patel signed the deal but retained his belief that the Nizam would reject it. [10] The Nizam, taking Razvi's advice, dismissed the plan. In September 1948, Patel made clear in Cabinet meetings that he intended to use force against the Nizam. [11] He obtained the agreement of the new Governor-General Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari and Prime Minister Nehru after some contentious debate, and under Operation Polo, sent the Army to invade Hyderabad. Between September 13 and 18th, Indian troops fought Hyderabadi troops and Razakars and defeated them. Patel retained the Nizam as the head of state as a conciliatory gesture. The main aim of Mountbatten and Nehru in attempting to achieve integration through diplomacy had been to avoid an outbreak of Hindu-Muslim violence. Patel insisted that if Hyderabad continued its independence, the prestige of the Government would be tarnished and then neither Hindus nor Muslims would feel secure in its realm. [12]

Conflicting agendas

Different theories have been proposed to explain the designs of Indian and Pakistani leaders in this period. Rajmohan Gandhi postulates that Patel believed that if Muhammad Ali Jinnah let India have Junagadh and Hyderabad, Patel would accept Kashmir acceding to Pakistan. [13] In his book Patel: A Life, Gandhi asserts that Jinnah sought to engage the questions of Junagadh and Hyderabad in the same battle. Some suggest that he wanted India to ask for a plebiscite in Junagadh and Hyderabad, knowing thus that the principle then would have to be applied to Kashmir, where the Muslim-majority would, he believed, vote for Pakistan. In a speech at the Bahauddin College in Junagadh following the latter's take-over, Patel said:

| “ | If Hyderabad does not see the writing on the wall, it goes the way Junagadh has gone. Pakistan attempted to set off Kashmir against Junagadh. When we raised the question of settlement in a democratic way, they (Pakistan) at once told us that they would consider it if we applied that policy to Kashmir. Our reply was that we would agree to Kashmir if they agreed to Hyderabad. [14] | ” |

Although only Patel's opinions rather than India's policy, and rejected by Nehru, both leaders felt angered at Jinnah's courting the princes of Jodhpur, Bhopal and Indore. [15] In her book The Sole Spokesman, Ayesha Jalal argues that Jinnah had never actually wanted partition, but once created, he wanted Pakistan to become a secular state inclusive to its Hindu minority and strategically secure from a geographically-larger India, thus encouraging Hindu states to join. When Jinnah remained adamant about Junagadh, and when the invasion of Kashmir began in September 1947, Patel exerted himself over the defense and integration of Kashmir into India. India and Pakistan clashed over Kashmir in 1965 and 1971, as well as over the sovereignty of the Rann of Kutch in August, 1965.

Integrating the Union

Many of the 565 states that had joined the Union had been very small and lacked resources to sustain their economies and support their growing populations. Many published their own currency, imposed restrictions and their own tax rules that impeded free trade. Although Prajamandals (People's Conventions) had been organized to increase democracy, a contentious debate opened over dissolving the very states India promised to officially recognize just months ago. Challenged by princes, Sardar Patel and V. P. Menon emphasized that without integration, the economies of states would collapse, and anarchy would arise if the princes proved unable provide democracy and govern properly. In December 1947, over forty states in central and eastern India merged into the Central Provinces and Orissa. Similarly, Patel obtained the unification of 222 states in the Kathiawar peninsula of his native Gujarat. In a meeting with the rulers, Menon said:

| “ | His Highness the Maharaja of Bhavnagar has already declared himself in favor of a United Kathiawar State. I may also remind you of the metaphor employed by Sardar Patel, of how a large lake cools the atmosphere while small pools become stagnant...It is not possible for 222 States to continue their separate existence for very much longer. The extinction of the separate existence of the States may not be palatable, but unless something is done in good time to stabilize the situation in Kathiawar, the march of events may bring more unpalatable results.[16] | ” |

In Punjab, the Patiala and East Punjab States Union formed. Madhya Bharat and Vindhya Pradesh emerged from the princely states of the former Central India Agency. Thirty states of the former Punjab Hill States Agency merged to form the Himachal Pradesh. A few large states, including Mysore, Kutch, and Bilaspur, remained distinct, but a great many more merged into the provinces. The Ministry of External Affairs administered the Northeast Frontier Agency (present-day Arunachal Pradesh and Nagaland) with the Governor of Assam. The Constitution of India, adopted on January 26, 1950, gave the states many powers, but the Union government had superior powers — including dissolving state governments if law and order collapsed.[17] Federalists emphasized creating national institutions to prevent factionalism and separatism. A common judiciary and the Indian Administrative Service and Indian Police Service emerged to help create a single government infrastructure. Most Indians welcomed the united leadership to fight social, economic challenges of India for the first time in thousands of years.

Pondicherry and Goa

See also: French India, Portuguese India

In the 1950s, France still maintained the regions of Pondicherry, Karikal, Yanaon, Mahe and Chandernagore as colonies and Portugal maintained Daman and Diu, Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Goa remained as colonies. India received control of the lodges in Machilipatnam, Kozhikode and Surat in October 1947. An agreement between France and India in 1948 agreed to an election in France's remaining Indian possessions to choose their political future. Chandernagore ceded to India on May 2, 1950, merging with West Bengal on October 2, 1955. On November 1, 1954, the four enclaves of Pondicherry, Yanaon, Mahe, and Karikal de facto transferred to the Indian Union and became the Union territory of Pondicherry. Portugal had resisted diplomatic solutions, and refused to transfer power. Dadra and Nagar Haveli incorporated into India in 1953 after bands of Indian irregulars occupied the lands, but Goa, Daman and Diu remained a bone of contention.

Arbitration by the World Court and the United Nations General Assembly favoured self-determination, but Portugal resisted all overtures from India. On December 18, 1961, in what Prime Minister Nehru termed as a police action, the Indian Army liberated Goa, Daman and Diu.[18] The Portuguese surrendered on December 19, and 3,000 Portuguese soldiers became prisoners of war. That take-over ended the last of the European colonies in India. In 1987, Goa achieved statehood.

States reorganization

The Constitution maintained the shape India's map &mdash, establishing three orders of states that preserved the territories and governing structures of the recent past. India's ethnically diverse population felt dissatisfied with colonial-era arrangements and centralized authority, which disempowered ethnic groups that formed an insignificant population in a province. The many regional languages of India lacked official use and recognition. Political movements arose in the regions demanding official use and autonomy for the Marathi-, Telugu-, Tamil-speaking regions of the Bombay state and Madras state. Incidents of violence grew in cities like Bombay and Madras as the demands gained momentum and became a potential source of conflict. Potti Sreeramulu undertook a fast-unto-death, demanding an Andhra state. Sreeramulu lost his life in the protest, but Andhra State soon emerged in 1953 out of the northern, Telugu-speaking districts of Madras state as a result of aroused popular support.

Prime Minister Nehru appointed the States Reorganisation Commission to recommend a reorganization of state boundaries along linguistic lines. The States Reorganisation Act of 1956, which went into effect on November 1, 1956, constituted the largest single change to state borders in the history of independent India. Bombay, Madhya Pradesh, Mysore, Punjab, and Rajasthan enlarged by the addition of smaller states and parts of adjacent states. Bombay, Mysore, and Andhra Pradesh states partitioned Hyderabad; the merging the Malayalam-speaking state of Travancore-Cochin with Malabar District of Madras state created the new linguistic state of Kerala.

On May 1, 1960, Bombay State, which had been enlarged by the Act, spun off Gujarat and Maharashtra as a result of conflicting linguistic movements. Violent clashes erupted in Mumbai and villages on the border with Karnataka over issues of Maharashtrian territory. Maharashtra still claims Belgaum as its own. In 1965, unrest broke out in Madras when Hindi took effect as India's national language.

Punjab and northeastern India

Across many regions, a culture of centralization met resented, seen as stifling regional autonomy and cultural identity. Inefficiency, corruption and economic stagnation in 1960s and 1970s aided thag argument. Although Punjab represented one of the most prosperous states, demands for greater autonomy and statehood arose. In 1966, Punjab divided into Sikh-majority Punjab and Hindu-majority Haryana, with their joint capital in Chandigarh, a union territory. Certain northern districts allocated to Himachal Pradesh. Jawaharlal Nehru had opposed creating separate states for different religious communities, but Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who faced pressure from the SGPC and leaders like Master Tara Singh carried it out. When the Khalistan insurgency created turmoil in the 1980s, the Army attacked militant encampments in the Golden Temple.[19] The bloody outcome outraged the Sikhs, who saw it as a desecration of their holiest shrine by the Government. A Sikh assassinated Indira Gandhi, triggering communal violence in Delhi. The Government employed martial law and force to crush the militant groups, but also began a process of devolving powers to the states as a means to end separatism. Punjab today stands as one of the most peaceful and prosperous states.

China refuses to recognize the McMahon Line which sets the framework of its boundary with India, laying claim to the territory of Arunachal Pradesh — briefly occupied by Chinese forces in the Sino-Indian War. In 1967, Chinese and Indian forces clashed at the Chola Border Post in Sikkim, whose merger China disputed with India, that finally reaching a resolution in 2003.[20] Nagaland, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Tripura, Manipur, and Assam, known as the Seven Sisters, became states between the 1970s and 1980s. In 1975, India under Indira Gandhi integrated Sikkim into the Union after a plebiscite resulted in an overwhelming vote in favor of merger with India, but the Army had to forcibly take control from the Chogyal. In the 1960–1970s, violent militancy arose in Assam and Nagaland.[21] Neglect and discrimination by the Union government, as well as poverty and cultural aversion, resulted in violence against refugees from Bangladesh and other settlers. The ULFA insurgency paralyzed Assam in the 1980s. Similar tensions in Mizoram and Tripura forced the Indian government to impose a martial law environment. The decline of popular appeal, increased autonomy, economic development and rising tourism has helped considerably reduce violence across the region.

Modern developments

Several new states emerged in 2000 — Chhattisgarh (from Madhya Pradesh), Jharkhand (from Bihar) and Uttarakhand (from Uttar Pradesh). That resulted from a national debate concerning the purported need to partition large states burdened with socioeconomic challenges, including overpopulation and the political marginalization of ethnic minorities. Such debate has continued: proposals for the creation of Vidarbha from Maharashtra, Telangana from Andhra Pradesh, Bundelkhand from parts of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, and Jammu and Ladakh from Kashmir have been forwarded.[22]

Correspondingly, governments have begun devolving power to regional levels as a means of increasing popular representation and administrative efficiency, as well as alleviating social problems. Those include disparities in economic growth — despite India's rapid economic development — and the corresponding easing of socioeconomic pressures faced by communities across those regions. Uttar Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh have formed special commissions for their Purvanchal, Rayalaseema, Telangana and Coastal Andhra regions. Groups, including self-appointed representatives of northeastern India's Bodo people, are pushing — often via violent insurgency — for either the formation of a Bodoland state or independence.[23] In 2003, the Union government, the state of Assam and the main Bodo separatist groups signed an agreement. That created the Bodoland Territorial Councils, which granted autonomy to regions with significant Bodo populations. Other groups have been pushing for the conferral of statehood upon Kutch, Cooch Behar, Gorkhaland, Kamtapur, Tulu Nadu, and Coorg.

See also

| Indian Independence Movement | |

|---|---|

| History: | Colonisation - British East India Company - Plassey - Buxar - British India - French India - Portuguese India - More... |

| Philosophies: | Indian nationalism - Swaraj - Gandhism - Satyagraha - Hindu nationalism - Indian Muslim nationalism - Swadeshi - Socialism |

| Events and movements: | Rebellion of 1857 - Partition of Bengal - Revolutionaries - Ghadar Conspiracy - Champaran and Kheda - Jallianwala Bagh Massacre - Non-Cooperation - Flag Satyagraha - Bardoli - 1928 Protests - Nehru Report - Purna Swaraj - Salt Satyagraha - Act of 1935 - Legion Freies Indien - Cripps' mission - Quit India - Indian National Army - Bombay Mutiny |

| Organisations: | Indian National Congress - Ghadar - Home Rule - Khudai Khidmatgar - Swaraj Party - Anushilan Samiti - Azad Hind - More... |

| Indian leaders: | Mangal Pandey - Rani of Jhansi - Bal Gangadhar Tilak - Gopal Krishna Gokhale - Lala Lajpat Rai - Bipin Chandra Pal - Mahatma Gandhi - M. Ali Jinnah - Sardar Patel - Subhash Chandra Bose - Badshah Khan - Jawaharlal Nehru - Maulana Azad - Chandrasekhar Azad - Rajaji - Bhagat Singh - Sarojini Naidu - Purushottam Das Tandon - Tanguturi Prakasam - Alluri Sitaramaraju - More... |

| British Raj: | Robert Clive - James Outram - Dalhousie - Irwin - Linlithgow - Wavell - Stafford Cripps - Mountbatten - More... |

| Independence: | Cabinet Mission - Indian Independence Act - Partition of India - Political integration - Constitution - Republic of India |

|

||||||||||

Notes

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life. (India: Navajivan, 1991. ASIN B0006EYQ0A), 406

- ↑ Manas: History and Politics [1] "Sardar Patel" University of California. accessdate 2006-10-27

- ↑ V. P. Menon. Integration of Indian States. (India: Orient Longman, 1998, ASIN: B0007ILF54), 99-100

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life, 411-412

- ↑ Gandhi. Patel: A Life, 413-414

- ↑ [2] The Constitution (26th Amendment) Act, 1971/. National Informatics Centre PHP, 2004-11-09. accessdate 2006-10-27

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life., 292

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life., 438

- ↑ 2006-05-08 [3]. Instrument of Accession. 2006-10-27, Hindustan Times.

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life., 480

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life., 481-482

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life., 483

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life., 430-438

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life., 438

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi. Patel: A Life., 407-408

- ↑ V. P. Menon. Integration of Indian States. 193-194

- ↑ President's Rule has been imposed frequently in states, especially during the Indian Emergency (1974–1977) under the Articles 352–360.

- ↑ Jagan Pillarisetti. [4]. Liberation of Goa. Bharat Rakshak, (PHP) accessdate 2006-10-27

- ↑ [5] JUNE 05, 1984, "Operation Bluestar" Bharat Rakshak (PHP) accessdate 2006-10-27

- ↑ [6] The Chola Incident. Bharat Rakshak (PHP) accessdate 2006-10-27

- ↑ K. P. S. Gill [7] "Isolation breeds terrorism" South Asia Terrorism Portal (PHP) accessdate 2006-10-27

- ↑ [8] Jammu State Demand Rediff.com. (PHP) accessdate 2006-10-27

- ↑ [9] Bodoland Insurgency Globalsecurity.org. (PHP) accessdate 2006-10-27

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Campbell-Johnson, Alan. 1985. Mission with Mountbatten. London: Hamilton. ISBN 9780241115367

- Gandhi, Rajmohan. 1990. Patel, a life. Ahmedabad: Navajivan Pub. House. OCLC: 25788696

- Hodson, H. V. 1985. The great divide Britain-India-Pakistan: with an epilogue written in 1985 which sums up the events since partition. Karachi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195773408

- Menon, V.P. Integration of Indian States. India: Orient Longman, 1998, ASIN: B0007ILF54

- Zubrzycki, John. 2006. The last Nizam- an Indian prince in the Australian outback. Sydney: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 9781405037228

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 10:26:44 | 55 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Political_integration_of_India | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF