The Chronicles Of Narnia

From Conservapedia

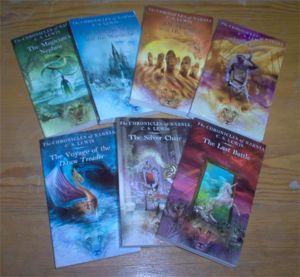

From Conservapedia The Chronicles of Narnia is a series of seven books written by C. S. Lewis. These books were written as a fictional story with allegorical connections to the Bible, and the Christian faith. Volumes of The Chronicles of Narnia were published yearly from 1950 to 1956. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe draws upon the Gospels, The Magician's Nephew covers the Creation account in the book of Genesis, and The Last Battle corresponds to the book of Revelation. Lewis's series, despite being popularly acclaimed, are the subject of Liberal censorship by the secular media. Despite this a series of three films have so far been made from the books and have been extremely popular with the public.

Lewis originally wrote the stories in a non-chronological order, with no particular plan for the series as a whole. Although Lewis later expressed a preference that the books be read in chronological order (starting with The Magician's Nephew) they have traditionally been read (and are being adapted to film) in order of publication. Because the events of each book are often separated by centuries and have limited overlap in their casts, either approach works.

Contents

- 1 Characters

- 2 Narnia Feature Films

- 3 Book 1: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe

- 4 Book 2: Prince Caspian

- 5 Book 3: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader

- 6 Book 4: The Silver Chair

- 7 Book 5: The Horse and His Boy

- 8 Book 6: The Magician's Nephew

- 9 Book 7: The Last Battle

- 10 Conservative Themes

- 11 Religious Criticisms

- 12 References

- 13 External links

Characters[edit]

- Aslan, the Lion—creator of Narnia.

- Jadis, Aslan's first and perhaps most dangerous enemy, known also as the White Witch

- Digory Kirke, who appears first as a small boy and in later installments as a learned and well-traveled professor. He attends the creation of Narnia and eventually is summoned to Aslan's side as Narnia enters its Last Days.

- Polly Plummer, Digory's boyhood friend, who joins him in his adventures.

- Andrew Ketterley, Digory's wicked and foolish uncle.

- Letitia Ketterley, Digory's aunt.

- Peter Pevensie, High King of Narnia during Narnia's Golden Age.

- Edmund Pevensie, Peter's younger brother, who is also crowned King Edmund the Just.

- Susan Pevensie, the elder of Peter's two sisters. Crowned Queen Susan the Gentle.

- Lucy Pevensie, the younger of Peter's two sisters. Crowned Queen Lucy the Valiant.

- Eustace Clarence Scrubb, their cousin. Obnoxious at first, but is changed by Aslan.

- Jill Pole, Eustace' schoolmate. Travels to Narnia with him.

- King Frank I, a London cabman who travels to creation of Narnia. He and his wife are crowned the first King and Queen of Narnia.

- Queen Helen, his wife.

- King Caspian, who must fight a war to claim his rightful inheritance and then sets out on a voyage of rescue and discovery.

- King Rilian, who must fight a battle of his own against a strange enchantment.

- King Trilian, present at the War of the Last Days.

Narnia Feature Films[edit]

Walt Disney and Walden Media have released three films based on these books. The first, The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, was released on December 9, 2005, and was a box office blockbuster. Prince Caspian was released on May 16, 2008, and was also popular. The other books in the series are now scheduled to be made into movies.[1] Voyage of The Dawn Treader was released on December 10, 2010.[2] A film adaptation of The Silver Chair is still in the works, however it will be a partial reboot, not featuring the cast from the first three films.[3]

Book 1: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe[edit]

(Second in Internal Chronology) This book is the first published of the seven Chronicles of Narnia (1950), written by Clive Staples Lewis, a noted Irish Christian writer. It introduces prominent characters to the series such as Aslan, Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy. The story begins with four children (Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy) being sent away to stay with an old professor, to keep them safe from the London Air Raids. The children find a magical wardrobe in an empty room, which leads into a magical world called Narnia. At that time, Narnia was under the spell and dominion of the White Witch, who had created a Hundred Year Winter. After Lucy's friend (Mr. Tumnus) is taken captive, the children set out to help the faun, and make right their coming into Narnia. After meeting up with friendly talking animals, and even the great lion Aslan, the children find they were sent into Narnia to fulfill a prophesy to free Narnia. It is no easy task and Aslan even gives his life to save Edmund from the justice of the Witch, after Edmund betrayed his family. In the end the four children are crowned Kings and Queens and Narnia enters the Golden Age. After many years, when they are adults in Narnia, they return to our world and find themselves children again.[4]

Book 2: Prince Caspian[edit]

(Fourth in Internal Chronology) This book involves the return to Narnia by the four children from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and how they again have to free Narnia from tyranny. They appear at their former castle which is now a ruin and meet the Dwarf Trumpkin. Trumpkin (thimbles and thunderbolts!) retells the history of young Prince Caspian whose Uncle Miraz holds the usurped throne. Caspian flees Miraz, joins the good Narnian creatures and engages in a war with the massive armies of his uncle. The children and the dwarf rush to Caspian's aide and meet Aslan on the way. They conquer Miraz's forces and reinstate Caspian as true king of Narnia. The children return their own world. The older children, Peter and Susan, are told they will not return to Narnia.[5]

Book 3: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader[edit]

(Fifth in Internal Chronology) Lucy, Edmund and their cousin, Eustace, return to Narnia (or more specifically to the seas of Narnia.) They meet Caspian who is sailing on the ship, Dawn Treader. King Caspian is exploring new seas and searching for the seven Narnian lords whom his Uncle Miraz had forced to sail away into exile. Caspian hopes to sail to the world's end. They sail across the seas finding new lands, some Lords, and survive many dangers. They sail to the end of the world, leaving the mouse, Reepicheep. Aslan sends the children home, telling Edmund and Lucy they won't return.[6]

Book 4: The Silver Chair[edit]

(Sixth in Internal Chronology) Eustace and his school friend, Jill Pole, go to Narnia where Aslan gives them the task of finding Old Caspian's son, Prince Rillian. Aslan gives them specific instructions to follow so they might find the Prince. They, along with the marshwiggle, Puddleglum, search the lands sometimes following, sometimes forgetting Aslan's instructions. They eventually find the Prince underground and held prisoner. They free him and fight a battle with a dangerous serpent. They return to Narnia where Rillian arrives in time to see his father Caspian die. Aslan then sends the children home.[7]

Book 5: The Horse and His Boy[edit]

(Third in Internal Chronology) This story is set back in the time when the original 4 children (Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy) rule in Narnia as kings and queens. The setting is to the south of Narnia, Calormene, where we meet Shasta, a young boy who is treated as a slave by his 'father.' When he learns that the old man isn't really his father, he makes a daring escape with the talking war horse Bree. Later on he meets up and travels with Aravis, a young royal girl running from a forced marriage, and her talking mare, Hwin. They travel across the deserts of Calormene and end up racing to Narnia and their ally, Archenland, to warn them of a Calormene invasion. They arrive in time and conquer the invaders. To his surprise, Shasta finds he is a twin son of the king of Archenland, and marries Aravis "so as to go on (arguing and making up) more conveniently."[8]

Book 6: The Magician's Nephew[edit]

(First in Internal Chronology) This story goes back to the original creation of Narnia and how the White Witch first came (she is called Queen Jadis.) It includes two children, Digory and Polly, who are tricked into entering other worlds by Digory's Uncle Andrew. They release the witch from her own world and bring her (along with Uncle Andrew, a London cabby, and a horse) into what would become Narnia. Aslan creates Narnia and commands Digory to heal the hurt he has started. In the end, Aslan returns the children to England and gives Digory some medicine to heal his dying mother.[9]

Book 7: The Last Battle[edit]

(Seventh and Final in Internal Chronology) The end of Narnia comes in this book. An evil ape, Shift, convinces a gullible donkey, Puzzle, to dress up in a lion's suit and pretend to be the great lion Aslan. The beasts of Narnia are thus deceived and enslaved by Shift, allowing the Calormenes to invade Narnia. Tirian, the true king of Narnia, is imprisoned but is freed by Jill and Eustace, who help mount a last ditch attack on the ape and the Calormenes. They are outnumbered and the evil Calormene god, Tash, enters Narnia, and takes in a stable where Eustace, Jill and the King are thrown. Fortunately Tash is cast out by High King Peter, who has appeared with Edmund, Lucy, Digory, and Polly (Susan no longer being a friend of Narnia) to witness Narnia's end. Aslan ends Narnia and leads all good creatures to a new Narnia, and out of the shadowlands. The children then learn that they all died in a railway accident and that they will remain there happily ever after.[10]

Conservative Themes[edit]

While the series is fantasy, there are clear references to real-world issues. Most of these references reflect conservative values.

- Criticism of atheism - In The Last Battle, the protagonists encounter a group of dwarfs. When Puzzle the donkey is revealed as a fraud, they reject the entire concept of Aslan, denying that he exists. They stubbornly refuse to accept even the most blatant evidence of his existence; when he growls at them, they claim that it's "done with a machine," echoing the liberal tendency to idolize technology and science over God.

- Criticism of public schools - In both The Voyage of the Dawn Treader and The Silver Chair, Lewis describes Eustace Scrubb's school—a "progressive" school where the students are allowed to run wild and disrespect for rules, traditions, and faith is encouraged. Needless to say, the school is not presented in a favorable light; Scrubb's fairly despicable personality in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader is presented as being largely a result of his time at this school (and his atheist parents.)

- The value of faith - On numerous occasions, the elder Pevensie siblings ignore Lucy, confident that their "superior knowledge" will lead them to the correct decision. Almost invariably, they turn out to be wrong; Lucy, with her unwavering faith, turns out to be correct time and time again, demonstrating that knowledge and experience without faith are of little value. Fortunately, the elder Pevensies are usually humble enough to admit this when it happens.

- Distinct gender roles - It is repeatedly made clear that the expectations are different for the male and female protagonists of the story. Susan and Lucy are both told that Aslan "does not mean for them to be in battle." On the other hand, both Peter and Edmund are expected to defend their sisters, if need be. However, this does not mean that Susan and Lucy are regarded as worthless; the series simply acknowledges that their role is different, but equally valuable. For example, although Lucy is not called on to fight, she is called on to save her brother and many of the other fallen warriors after the battle, a crucial task.

Religious Criticisms[edit]

While the Narnian[11] series is often described as a Christian allegory similar to Pilgrim's Progress, some Christians have raised theological problems with the books. Many such concerns can be dealt with to some extent by a closer look at the text.

- Endorsement of astrology - Signs seen in the stars are frequently used as an irrefutable truth by the natives of Narnia. Apologists have claimed astrology is being used to symbolize Biblical prophesy. This would mean the Narnia books are deliberately using a forbidden form of divination to represent Biblical prophesy.

- Response: In Narnia, the stars are sentient beings. In both Voyage of the Dawn Treader and Last Battle, the protagonists meet stars.

- Prince Caspian marries Satan's daughter - Keen readers have noted that at the end "Voyage of the Dawn Treader" Prince Caspian marries the daughter of a star that has been cast out of the sky. In the Book of Revelations stars are used to symbolize the angels who joined Satan in his rebellion against God and fell from Heaven. When asked what a star could do to be cast down from Heaven, the fallen star declines to answer, only implying the answer would disturb Caspian and his crew.

- Response: There is no textual evidence to support this analogy. Indeed, the "retired star" and his daughter both honor Aslan (Jesus). In Silver Chair, we see that Caspian's child by the star's daughter grows up to be an honorable man.

- Aslan is distinct from his Father - Despite being used as a Christ figure in "The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe" the prospect of a trinity is never raised. Aslan is depicted as distinct from his father, and no hint of a Holy Spirit analog surfaces. This, at best, leaves Aslan as an incomplete metaphor for Christ.

- Breeding between species is common - Despite Biblical injunctions against mixing species, several characters are a blend of human and non-human ancestry. The most notable of these figures is the tutor of Prince Caspian, who is part dwarf.

- Response: No such prohibition is given in Narnia. In addition, the narrative never commends Dr. Cornelius's heritage. Indeed, some dwarves want to kill him for it; the conclusion is that "he can't help his parentage."

- Satanic figures used as heroes - Lucy meets a pan like character on her first visit to Narnia. The figure has horns and a lower body resembling that of a goat. Both traits are traditionally associated with artist representations of Satan, or with the pagan figure Pan, known for lasciviousness, drunkenness and sexual assault. In short, she meets a minor demon, and he becomes a "good guy."

- Response: Lewis did not mean to introduce the negative characteristics of the mythological figures. He viewed them as parts of his imagination having been "redeemed" through his (Lewis's) coming to Christ, as is shown in Prince Caspian, when Susan says, "I don't think we'd be quite safe around Silenus without Aslan."

- Universal Celibacy is demanded of the heroes into adulthood. Marriage is not permitted - At the conclusion of the series, three of the four human characters from "The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe" enter a "new" Narnia, an apparent analog for Heaven. Susan however does not enter the new Narnia, having been excluded from further attachment to Narnia by her lifestyle on Earth. The text is vague on the specifics, but she appears to have been exercised for either pursuing a promiscuous lifestyle or for trying to find a husband. This means Narnia, intended as an analog for Heaven, does not permit those who have married or tried to marry. It's important to note that Lewis himself was celibate at the time he wrote the Narnia series and did not marry until well after their publication, as fictionalized in the movie "Shadowlands." One meaning that can be derived from Susan's exclusion is that Lewis, at the time, believed that only the celibate faithful entered the Kingdom of Heaven. Lewis' view of marriage is further highlighted by the fact that the text leaves the reader unable to tell if Susan has become a Jezebel or is pursuing a Christ centered marriage. The text seems to equate the two.

- Response: The Pevenseys' parents are also present, so married Christians are clearly not excluded from Heaven. What the characters criticize Susan for is not pursuing a Godly marriage but refusing to pay any attention to Christ. (In addition, as this world has not ended in Last Battle, Susan remains alive - she can definitely repent later, as Lewis himself pointed out in a letter to one reader.)

References[edit]

- ↑ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, Directed by Andrew Adamson, Produced by Mark Johnson, Philip Steuer, 2005.

- ↑ http://www.comingsoon.net/news/movienews.php?id=52379

- ↑ http://www.comingsoon.net/movies/news/647133-the-chronicles-of-narnia-the-silver-chair-movie-will-be-a-total-reboot

- ↑ The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis, Macmillan Publishing Co, 1970.

- ↑ Prince Caspian by C.S. Lewis, Macmillan Publishing Co. 1970.

- ↑ The Voyage of the Dawn Treader by C.S. Lewis, Macmillan Publishing Co.1970.

- ↑ The Silver Chair by C.S. Lewis, Macmillan Publishing Co. 1970.

- ↑ The Horse and His Boy by C.S. Lewis, Macmillan Publishing Co.1970. p.216.

- ↑ The Magician's Nephew by C.S. Lewis, Macmillan Publishing Co. 1970.

- ↑ The Last Battle by C.S. Lewis, Macmillam Publishing Co. 1970.

- ↑ Lewis himself preferred this adjective form

External links[edit]

- C.S. Lewis Society of California

- Marion E. Wade Center, Wheaton College

- "God’s Storyteller: The Curious Life and Prodigious Influence of C. S. Lewis, the Man Behind The Chronicles of Narnia, by Jay Tolson," by Jay Tolson

- "Narnia and the Seven Deadly Sins," by Don W. King

- "The Woman Who Drew Narnia: Pauline Baynes," by Charlotte Cory

- C.S. Lewis Foundation

- Into the Wardrobe

- "Stay Out of Our Wardrobe! The Libertarian Narnia State," by R. Andrew Newman

- Chronicles of Narnia official films site

- "The Childlike in George MacDonald and C. S. Lewis," by Don W. King

- "The View from Other Worlds—Seeing Ourselves with God’s Eyes," by Luci Shaw

Categories: [Novels] [Narnia] [Science Fiction Movies] [Fiction] [Movies] [Novels] [Science Fiction] [Christian Fiction] [Christian Movies]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/19/2023 07:10:14 | 33 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/The_Chronicles_of_Narnia | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF