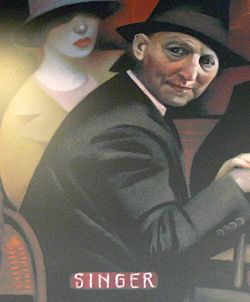

Isaac Bashevis Singer

From Nwe

From Nwe

Isaac Bashevis Singer (Yiddish: יצחק באַשעװיס זינגער) (November 21, 1904 – July 24, 1991) was a Nobel Prize-winning Polish born American writer of both short stories and novels. He wrote in Yiddish. From a traditional Jewish village, he would move to the United States to flee the Nazis during World War II. Most of his literature addresses the cultural clash between the values of traditional society, which he learned first and foremost in his own family, and those of modern society which he encountered after his flight to the New World.

Biography

Isaac Bashevis Singer was born in 1902 in Leoncin, a small village inhabited mainly by Jews near Warsaw in Poland, then part of the Russian Empire, probably on November 21, 1902. (This would concur with the date and month he admitted in private to his official biographer Paul Kresh[1], his secretary Dvorah Telushkin ([2] and with the historical events he and his brother refer to in their childhood-memoirs. The usual, official date of birth—July 14, 1904—had been freely decided upon by the author in his early youth, most probably making himself younger to avoid the draft; the family moved to Radzymin, often erroneously cited as his birthplace, some years later.) His father was a Hasidic rabbi and his mother, Bathsheba, was the daughter of the rabbi of Bilgoraj. Singer later used her name in his pen name "Bashevis" (son of Bathsheba). His brother Israel Joshua Singer also was a noted writer. Their elder sister, Esther Kreitman, was also a writer. She was the first in the family to write stories.[3]

The family moved to the court of the Rabbi of Radzymin in 1907, where his father became head of the Yeshiva. After the Yeshiva-building burned down, the family moved to Krochmalna-Street in the Yiddish-speaking poor Jewish quarter of Warsaw in 1908, where Singer grew up. There his father acted as a rabbi–that is, as judge, arbitrator, religious authority and spiritual leader.[4]

In 1917 the family had to split up because of the hardships of World War I, and Singer moved with his mother and younger brother Moshe to his mother's hometown of Bilgoraj, a traditional Jewish village or shtetl, where his mother's brothers had followed his grandfather as rabbis. When his father became a village-rabbi again in 1921, Singer went back to Warsaw, where he entered the Tachkemoni Rabbinical Seminary, but found out that neither the school nor the profession suited him. He returned to Bilgoraj, where he tried to support himself by giving Hebrew lessons, but soon gave up and joined his parents, considering himself a failure. But in 1923 his older brother Israel Joshua arranged for him to move to Warsaw to work as a proofreader for the Literarische Bleter, of which he was an editor.[5]

Singer's first published story won the literary competition of the literarishe bletter and he soon got a name as a promising talent. A reflection of his formative years in "the kitchen of literature" (his own expression)[2] can be found in many of his later works. I. B. Singer's first novel was Satan in Goray which he first published in installments in a literary magazine, Globus, which he had founded with his life-long friend, the Yiddish poet Aaron Zeitlin in 1935. It tells the story of the events in the village of Goraj (close to Bilgoraj), after the terrible catastrophe of 1648, where the Jews of Poland lost a third of their population in a cruel uprising by Cossacks and the effects of the seventeenth century faraway false messiah Shabbatai Zvi on the local population. Its last chapter is written in the style imitative of medieval Yiddish chronicle. The people in this novel, as elsewhere with Singer, are often at the mercy of the capricious infliction of circumstance, but even more their own passions, manias, superstitions and fanatical dreams. In its stark depiction of innocence crushed by circumstance it appears like a foreboding of the coming danger. In his later work The Slave (1962) Singer returned to the aftermath of 1648 again, in a love story of a Jewish man and a Gentile woman, where he shows the traumatized and desperate survivors of a historic catastrophe with even deeper understanding.

Immigration to America

To flee from approaching fascism, Singer emigrated, once again with the help of his brother, to the U.S. in 1935. In so doing, he separated from his first wife Rachel, and son Israel, who went to Moscow and later Palestine. Singer settled in New York, where he started writing as a journalist and columnist for The Forward (Yiddish: פֿאָרװערטס), a Yiddish-language newspaper. After a promising beginning, he became despondent and, for some years, felt "Lost in America" which became the title of a Singer novel, in Yiddish (1974) and in English (1981). In 1938, he met Alma Wassermann, born Haimann, a German-Jewish refugee from Munich, whom he married in 1940. With her at his side, he became a prolific writer again and, in due course, a valued contributor to the Jewish Daily Forward with so many articles that he used, besides "Bashevis," the pen names "Varshavsky" and "D. Segal".

However, he became an actual literary contributor to the Forward only after his brother's death in 1945, when he published "The Family Moskat," which he wrote in honor of his older brother. But his own style showed in the daring turns of his action and characters–with (and this in the Jewish family-newspaper in 1945) double adultery in the holiest of nights of Judaism, the evening of Yom Kippur. He was almost forced to stop the novel by the legendary editor in chief, Abraham Cahan, but was saved through his readers, who wanted the story to go on. After this, his stories—which he had published in Yiddish literary newspapers before*mdash;were printed in the Jewish Daily Forward too. Throughout the 1940s, Singer's reputation began to grow. After World War II and the near destruction of the Yiddish-speaking peoples, Yiddish seemed a dead language. Though Singer had moved to the United States, he believed in the power of his native language and was convinced that there was still a large audience that longed to read in Yiddish. In an interview in Encounter a literary magazine published in London (Feb. 1979), he claimed that although the Jews of Poland had died, "something—call it spirit or whatever—is still somewhere in the universe. This is a mystical kind of feeling, but I feel there is truth in it."

Some say that Singer's work is indebted to the great writers of Yiddish tradition such as Sholom Aleichem, and he himself considered his older brother his greatest artistic example. But actually he was more influenced by Knut Hamsun, whom he read (and translated) in his youth, and whose subjective approach he transferred to his own world, which, contrary to Hamsun's, was not only shaped by the ego of its characters, but by the moral commitments of the Jewish traditions he grew up with and which his father embodies in the stories about his youth. This led to the dichotomy between the life his heroes led and the life they feel they should lead–which gives his art a modernity his predecessors do not have. His themes of witchcraft, mystery and legend draw on traditional sources, but they are contrasted with a modern and ironic consciousness. They are also concerned with the bizarre and the grotesque.

Singer always wrote and published in Yiddish (almost all of it in newspapers) and then edited his novels and stories for the American version, which became the base for all the other translations (he talked of his "second original"). This has led to an ongoing controversy where the "real Singer" can be found–in the Yiddish original, with its finely tuned language, and, sometimes, rambling construction, or in the tightly edited American version, where the language is usually simpler and more direct. Many stories and novels of I. B. Singer have not been translated yet.

Literary career

Singer published at least 18 novels, 14 children's books, a number of memoirs, essays and articles, but he is best known as a writer of short stories which have appeared in over a dozen collections. The first collection of Singer's short stories in English, Gimpel the Fool, was published in 1957. The title story was translated by Saul Bellow and published in May 1953 in Partisan Review. Selections from Singer's "Varshavsky-stories" in the Daily Forward were later published in anthologies as My Father's Court (1966). Later collections include A Crown of Feathers (1973), with notable masterpieces in between, such as The Spinoza of Market Street (1961) and A Friend of Kafka (1970). The world of his stories is the world and life of East European Jewry, such as it was lived in cities and villages, in poverty and persecution, and imbued with sincere piety and rites combined with blind faith and superstition. After his many years in America, his stories also concerned themselves with the world of the immigrants and the way they pursue the American dream, which proved elusive both when they obtain it, as Salomon Margolin, the successful doctor of "A Wedding in Brownsville" (in Short Friday), who finds out his true love was killed by the Nazis, or when it escapes them as it does the "Cabalist of East Broadway" (in A Crown of Feathers), who prefers the misery of the Lower East Side to an honored and secure life as a married man. It appears to include everything–pleasure and suffering, coarseness and subtlety. We find obtrusive carnality, spicy, colorful, fragrant or smelly, lewd or violent. But there is also room for sagacity, worldly wisdom and humor.

Themes

One of Singer's most prominent themes is the clash between the old and the modern world, tradition and renewal, faith and free thought. Among many other themes, it is dealt with in Singer's big family chronicles - the novels, The Family Moskat (1950), The Manor (1967), and The Estate (1969). These extensive epic works have been compared with Thomas Mann's novel, Buddenbrooks. (Singer had translated Mann's Der Zauberberg (The Magic Mountain) into Yiddish as a young writer.) Like Mann in Buddenbrooks, Singer describes how old families are broken up by the new age and its demands, from the middle of the nineteenth century up to the Second World War, and how they are split, financially, socially and humanly.

One of his most famous novels (due to a popular movie remake) was Enemies, a Love Story in which a Holocaust survivor deals with his own desires, complex family relationships, and the loss of faith. Singer's feminist story "Yentl" has had a wide impact on culture since being made into a popular movie starring Barbra Streisand. Perhaps the most fascinating Singer-inspired film is "Mr. Singer’s Nightmare or Mrs. Pupkos Beard" (1974) by Bruce Davidson, a renowned photographer who became Singer's neighbor. This unique film is a half-hour mixture of documentary and fantasy for which Singer not only wrote the script but played the leading part.

Throughout the 1960s, Singer continued to write on questions of personal morality, and was the target of scathing criticism from many quarters during this time, some of it for not being "moral" enough, some for writing stories that no one wanted to hear. Singer's relationship with religion was complex. He regarded himself as a skeptic and a loner, though he still felt connected to his Orthodox roots, and ultimately developed his own brand of religion and philosophy which he called a "private mysticism."

After being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1978, Singer gained a monumental status among writers throughout the world, and his reputation with non-Jewish audiences is now higher than that of any other Yiddish writer.

Singer died on July 24, 1991 in Miami, Florida, after suffering a series of strokes.

Vegetarianism

Singer was a prominent vegetarian for the last 35 years of his life and often included such themes in his works. In his short story, The Slaughterer, he described the anguish that an appointed slaughterer had trying to reconcile his compassion for animals with his job of slaughtering them. He felt that the eating of meat was a denial of all ideals and all religions: "How can we speak of right and justice if we take an innocent creature and shed its blood." When asked if he had become a vegetarian for health reasons, he replied: "I did it for the health of the chickens."

In The Letter Writer, he wrote "In relation to [animals], all people are Nazis; for the animals, it is an eternal Treblinka."[6]

In the preface to Steven Rosen's "Food for Spirit: Vegetarianism and the World Religions" (1986), Singer wrote:

"When a human kills an animal for food, he is neglecting his own hunger for justice. Man prays for mercy, but is unwilling to extend it to others. Why should man then expect mercy from God? It's unfair to expect something that you are not willing to give. It is inconsistent. I can never accept inconsistency or injustice. Even if it comes from God. If there would come a voice from God saying, 'I'm against vegetarianism!' I would say, 'Well, I am for it!' This is how strongly I feel in this regard." [7]

List of works

Note: the publication years in the following list refer to English translations, not the Yiddish originals (which often predate their translations by ten or twenty years).

- The Family Moskat (1950)

- Satan in Goray (1955)

- The Magician of Lublin (1960)

- The Slave (1962)

- Zlateh the Goat (1966)

- The Fearsome Inn (1967)

- Mazel and Shlimazel (1967)

- The Manor (1967)

- The Estate (1969)

- The Golem (1969)

- A Friend of Kafka, and Other Stories (1970)

- Elijah The Slave (1970)

- Joseph and Koza: or the Sacrifice to the Vistula (1970)

- The Topsy-Turvy Emperor of China (1971)

- Enemies, a Love Story (1972)

- The Wicked City (1972)

- The Hasidim (1973)

- Fools of Chelm (1975)

- Naftali and the Storyteller and His Horse, Sus (1976)

- A Little Boy in Search of God (1976)

- Shosha (1978)

- A Young Man in Search of Love (1978)

- The Penitent (1983)

- Yentl the Yeshiva Boy (1983) (basis for the movie Yentl)

- Why Noah Chose the Dove (1984)

- The King of the Fields (1988)

- Scum (1991)

- The Certificate (1992)

- Meshugah (1994)

- Shadows on the Hudson (1997)

see also:

- Rencontre au Sommet (86-page transcript in book form of conversations between Singer and Anthony Burgess) (in French, 1998)

Bibliographies:

- Miller, David Neal. Bibliography of Isaac Bashevis Singer, 1924-1949, New York, Bern, Frankfurt: Nancy, 1984.

- Saltzman, Roberta. Isaac Bashevis Singer, A Bibliography of His Works in Yiddisch and English, 1960-1991, Lanham, MD, and London: 2002.

Secondary Literature:

- Carr, Maurice. "My Uncle Itzhak: A Memoir of I. B. Singer," Commentary, (December 1992)

- Goran, Lester. The Bright Streets of Surfside. The Memoir of a Friendship with Isaac Bashevis Singer, Kent, OH: 1994.

- Hadda, Janet. Isaac Bashevis Singer: A Life, New York: 1997.

- Kresh, Paul. Isaac Bashevis Singer: The Magician of West 86th Street, New York: 1979

- Sussman, Jeffrey. "Recollecting Isaac Bashevis Singer." Jewish Currents magazine and The East Hampton Star

- Telushkin, Dvorah. Master of Dreams, A Memoir of Isaac Bashevis Singer, New York: 1997.

- Tree, Stephen. Isaac Bashevis Singer, Munich: 2004. (in German)

- Tuszynska, Agata. Lost Landscapes, In Search of Isaac Bashevis Singer and the Jews of Poland, Transl. by M. G. Levine, New York: 1998.

- Wolitz, Seth (ed.) The Hidden Isaac Bashevis Singer, University of Texas Press, 2002.

- Zamir, Israel. "Journey to My Father Isaac Bashevis Singer," New York: 1995.

- Ziółkowska, Aleksandra. Korzenie są polskie, Warszawa: 1992. ISBN 8370664067

- Ziolkowska-Boehm, Aleksandra. The Roots Are Polish, Toronto: 2004. ISBN 0920517056

Notes

- ↑ Paul Kresh, Isaac Bashevis Singer, The Magician of West 86th Street, A Biography, (The Dial Press, New York 1979): 390.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Dvorah Telushkin, Master of Dreams, A Memoir of Isaac Bashevis Singer (New York, 1997).

- ↑ Maurice Carr, "My Uncle Itzhak: A Memoir of I. B. Singer," Commentary (December 1992)

- ↑ Isaac Bashevis Singer, In my Father's Court, (New York: Fawcett Crest, 1966)

- ↑ Isaac Bashevis Singer, A Little Boy in Search of God, (New York: Doubleday, 1976)

- ↑ [1]Quotation using phrase "Eternal Treblinka". Retrieved September 18, 2007.

- ↑ Steven Rosen, Food for the Spirit: Vegetarianism and the World Religions, (Bala Books, 1987) ISBN 0896470229

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carr, Maurice. "My Uncle Itzhak: A Memoir of I. B. Singer," In: Commentary (December 1992).

- Kresh, Paul. Isaac Bashevis Singer, The Magician of West 86th Street, A Biography, New York: The Dial Press, 1979. ISBN 9780803736962

- Telushkin, Dvorah. Master of Dreams: A Memoir of Isaac Bashevis Singer, New York: Harper Perennial, 1997. ISBN 9780060739331

External links

All links retrieved March 6, 2018.

- 1978 Nobel Prize in Literature

- Nobel biography

- What Yiddish Says article from The Weekly Standard.

- PBS American Masters: Isaac Bashevis Singer.

- Isaac Singer's Gravesite

- Bibliotheca Augustana Yidish lebn – a muster far ale felker. nobel-lektsye gehaltn fun y.b. singer in der shvedisher akademye dem 8tn detsember 1978 in shtokholm. (in Norwegian)

1976: Saul Bellow | 1977: Vicente Aleixandre | 1978: Isaac Bashevis Singer | 1979: Odysseas Elytis | 1980: Czesław Miłosz | 1981: Elias Canetti | 1982: Gabriel García Márquez | 1983: William Golding | 1984: Jaroslav Seifert | 1985: Claude Simon | 1986: Wole Soyinka | 1987: Joseph Brodsky | 1988: Naguib Mahfouz | 1989: Camilo José Cela | 1990: Octavio Paz | 1991: Nadine Gordimer | 1992: Derek Walcott | 1993: Toni Morrison | 1994: Kenzaburo Oe | 1995: Seamus Heaney | 1996: Wisława Szymborska | 1997: Dario Fo | 1998: José Saramago | 1999: Günter Grass | 2000: Gao Xingjian |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 07:13:20 | 7 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Isaac_Bashevis_Singer | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed: KSF

KSF