Crystal

From Nwe

From Nwe

In chemistry and mineralogy, a crystal is defined as a solid in which the constituent atoms, molecules, or ions are packed in a regularly ordered, repeating pattern that extends in all three spatial dimensions. Colloquially, the term crystal is applied to solid objects that exhibit well-defined geometric shapes, often pleasing in appearance. The scientific study of crystals and crystal formation is called crystallography.

Many types of crystals are found in nature. Snowflakes, diamonds, and common salt are well-known examples. In fact, the wide variety of minerals—ranging from single elements and simple salts to complex silicates—are crystalline materials. The structures of crystals depend on the types of bonds between the atoms and the conditions under which the crystals are formed.

Various minerals are the raw materials from which metals are extracted, and the metals themselves have crystalline structures. Other minerals are used as gemstones, which have been historically sought after for their aesthetic appeal. In addition, gems have been said to possess healing properties. Today, solid-state laser materials are often made by doping a crystalline solid (such as corundum) with appropriate ions. Quartz crystals are used to make "oscillators" that provide a stable timing signal for wristwatches and digital integrated circuits, and stabilize radio transmitter frequencies. Mica crystals are used in the manufacture of capacitors and insulation for high-voltage electrical equipment. Diamonds are well suited for cutting, polishing, grinding, and engraving tools.

Crystallization

The process of formation of crystals is known as crystallization. This process may occur when a material in the gas or liquid phase is cooled to the solid phase, or when a substance comes out of solution by precipitation or evaporation of the solvent. The type of crystal structure formed from a fluid depends on the chemistry of the fluid and the conditions under which the crystallization process occurs.

Crystallization can be a natural or artificial process. When the conditions are appropriately regulated, the product may be a single crystal in which all the atoms of the solid fit into the same crystal structure. Examples of single crystals that are large enough to see and handle include gems, silicon crystals prepared for the electronics industry, and crystals of a nickel-based superalloy for turbojet engines. The formation of such single crystals, however, is rare. Generally, many crystals form simultaneously, leading to a polycrystalline solid. For example, most metals are polycrystalline solids. In addition, crystals are often symmetrically intergrown to form "crystal twins."

A domain of solid-state matter that has the same structure as a single crystal is called a crystallite. A polycrystalline material is made up of a large number of crystallites held together by thin layers of amorphous solid. The size of a crystallite can vary from a few nanometers to several millimeters. Metallurgists often refer to crystallites as grains, and the boundary between two crystallites is known as the grain boundary.

Under certain conditions, a fluid may solidify into a noncrystalline state. In most cases, this involves cooling the fluid so rapidly that its atoms cannot travel to their lattice sites before they lose mobility. A noncrystalline material, which has no long-range order, is called an amorphous, vitreous, or glassy material.[1]

Crystallization from solution

For a substance (solute) to be crystallized out of a solution, the solution must be "supersaturated." This means that the solution has to contain more of the substance in dissolved form than it would contain under conditions of saturation (at equilibrium).

The formation of solid crystals from a homogeneous solution consists of two major stages: nucleation and crystal growth. Chemists and biochemists use this process as a technique to purify substances from solution.

In the nucleation stage, the solute molecules dispersed in the solvent start to gather to create clusters, which first occurs on the nanometer scale. If the clusters are stable under the prevailing conditions, they become the nuclei from which crystals will grow. If the clusters are not stable, they redissolve. Therefore, the clusters need to reach a critical size to become stable nuclei. The critical size is dictated by the operating conditions, such as temperature and supersaturation. It is at the stage of nucleation that the atoms become arranged in a defined and periodic manner that defines the crystal structure.

The stage of crystal growth involves growth of the nuclei that have successfully achieved the critical cluster size. Subsequently, nucleation and growth continue to occur simultaneously, as long as the solution is supersaturated. Supersaturation is the driving force of the crystallization process, controlling the rate of nucleation and crystal growth.

Depending on the conditions, either nucleation or growth may predominate over the other. As a result, crystals with different sizes and shapes are obtained. (The control of crystal size and shape constitutes one of the main challenges in industrial manufacturing, such as for pharmaceuticals). Once the supersaturated state is exhausted, the solid-liquid system reaches equilibrium and the crystallization process is completed, unless the operating conditions are modified to make the solution supersaturated again.

Crystallization in nature

There are many examples of crystallization in nature. They include the formation of:

Artificial methods of crystallization

To carry out the crystallization process artificially, the solution is supersaturated by various methods:

- cooling the solution

- evaporation of the solvent

- addition of a second solvent that reduces the solubility of the solute

- changing the pH (acidity or basicity) of the solution

- chemical reaction

Crystalline materials

Crystalline structures occur in all classes of materials, with all types of chemical bonds. Almost all metals exist in a polycrystalline state. Amorphous or single-crystal metals may be produced synthetically, often with great difficulty. Ionically bonded crystals are often formed from salts, when the salt is solidified from a molten fluid or when it is crystallized out of a solution. Covalently bonded crystals are also common, notable examples being diamond, silica, and graphite. Weak interactions, known as Van der Waals forces, can also play a role in a crystal structure; for example, this type of bonding loosely holds together the hexagonal-patterned sheets in graphite. Polymers generally form crystalline regions, but the lengths of the molecules usually prevents complete crystallization.

Some crystalline materials may exhibit special electrical properties, such as the ferroelectric effect or the piezoelectric effect (see crystal symmetry and physical properties below). Additionally, light passing through a crystal is often bent in different directions, producing an array of colors. The study of these effects is called crystal optics.

Most crystalline materials have a variety of crystallographic defects. The types and structures of these defects can have a profound effect on the properties of the materials.

Crystal structure

In the scientific study of crystals, the term crystal structure refers to the unique, symmetrical arrangement of atoms in a crystal. It does not refer to the external, macroscopic properties of the crystal, such as its size and shape.

The crystal structure of a material is often discussed in terms of its unit cell, which consists of a particular arrangement of a set of atoms. The unit is repeated periodically in three dimensions, forming a lattice called a "Bravais lattice." The spacing of unit cells in various directions is called the lattice parameters. A crystal's structure and symmetry play a role in determining many of its properties, such as cleavage, electronic band structure, and optical properties.

Unit cell

The unit cell is described by its lattice parameters—the lengths of the cell's edges and the angles between them. The positions of the atoms within the unit cell are described by the set of atomic positions measured from a lattice point.

For each crystal structure, there is a conventional unit cell, which is the smallest unit that has the full symmetry of the crystal (see below). The conventional unit cell is not always the smallest possible unit. A primitive unit cell is the smallest possible unit one can construct such that, when tiled, it completely fills space. The primitive unit cell, however, does not usually display all the symmetries inherent in the crystal. A Wigner-Seitz cell is a particular type of primitive cell that has the same symmetry as the lattice.

Classification of crystals by symmetry

The defining property of a crystal is the inherent symmetry of the positions of its atoms. For example, suppose a crystal is rotated by 180 degrees about a certain axis, and the new atomic configuration is identical to the original configuration. The crystal is then said to have "two-fold rotational symmetry" about this axis. Also, a crystal may have "mirror symmetry," in which the atoms are symmetrically placed on both sides of a mirror-like plane; or it may have "translational symmetry," in which the atomic structure is reproduced when the atoms are moved along a certain axis. A combination of such symmetries is called "compound symmetry." A complete classification of a crystal is achieved when all its inherent symmetries are identified.

Crystal systems

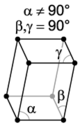

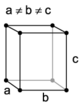

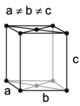

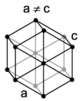

Crystal structures may be grouped according to the axial system used to describe their lattice. These groupings are called crystal systems. Each crystal system consists of a set of three axes in a particular geometrical arrangement.

There are seven unique crystal systems. The simplest and most symmetric of these is the cubic (or isometric) system, which has the symmetry of a cube—the three axes are mutually perpendicular and of equal length. The other six systems, in order of decreasing symmetry, are hexagonal, tetragonal, rhombohedral (also known as trigonal), orthorhombic, monoclinic, and triclinic. Some crystallographers consider the hexagonal crystal system to be part of the trigonal crystal system. The crystal system and Bravais lattice of a crystal describe the (purely) translational symmetry of the crystal.

The Bravais lattices

When the crystal systems are combined with the various possible lattice centerings, we arrive at the Bravais lattices. They describe the geometric arrangement of the lattice points, and thereby the translational symmetry of the crystal. In three dimensions, there are 14 unique Bravais lattices that are distinct from one another in the translational symmetry they contain. All known crystalline materials (not including quasicrystals) fit into one of these arrangements. The 14 three-dimensional lattices, classified by crystal system, are shown on the right. The Bravais lattices are sometimes referred to as space lattices.

The crystal structure consists of the same group of atoms, the basis, positioned around each and every lattice point. This group of atoms therefore repeats indefinitely in three dimensions according to the arrangement of the particular Bravais lattices. The characteristic rotation and mirror symmetries of the group of atoms, or unit cell, is described by its "crystallographic point group."

Point groups and space groups

The crystallographic point group or crystal class is the set of non-translational symmetry operations that leave the appearance of the crystal structure unchanged. These symmetry operations can include (a) mirror planes, which reflect the structure across a central plane; (b) rotation axes, which rotate the structure a specified number of degrees; and (c) a center of symmetry or inversion point, which inverts the structure through a central point. There are 32 possible crystal classes, each of which can be placed in one of the seven crystal systems.

The space group of the crystal structure is composed of translational symmetry operations, in addition to the operations of the point group. These include (a) pure translations, which move a point along a vector; (b) screw axes, which rotate a point around an axis while translating parallel to the axis; and (c) glide planes, which reflect a point through a plane while translating it parallel to the plane. There are 230 distinct space groups.

Crystal symmetry and physical properties

Twenty of the 32 crystal classes are described as piezoelectric, which means that they can generate a voltage in response to applied mechanical stress. All 20 piezoelectric classes lack a center of symmetry.

Any material develops a dielectric polarization (charge separation) when an electric field is applied, but a substance that has natural charge separation even in the absence of an electric field is called a polar material. Whether or not a material is polar is determined solely by its crystal structure. Only 10 of the 32 point groups are polar. All polar crystals are pyroelectric, so the 10 polar crystal classes are sometimes referred to as the pyroelectric classes.

A few crystal structures, notably the perovskite structure, exhibit ferroelectric behavior. This property is analogous to ferromagnetism. In the absence of an electric field during production, the crystal does not exhibit polarization, but upon application of an electric field of sufficient magnitude, the ferroelectric crystal becomes permanently polarized. This polarization can be reversed by a sufficiently large counter-charge, in the same way that a ferromagnet can be reversed. It should be noted that although these materials are called ferroelectrics, the effect is due to their crystal structure, not the presence of a ferrous metal.

Defects in crystals

Real crystals feature defects or irregularities in the ideal arrangements described above. These defects critically determine many of the electrical and mechanical properties of real materials. For example, dislocations in the crystal lattice allow shear at much lower stress than that needed for a perfect crystal structure.

Crystal habit

A mineralogist often describes a mineral in terms associated with the apparent shape and size of its crystals. For example, a branching structure is described as dendritic; a star-like, radiating form is called stellate; a structure with needle-shaped crystals is called acicular. Such a description is known as the crystal habit of the mineral. A list of crystal habits is given below.

The various terms used for crystal habits are useful in communicating the appearance of mineral specimens. Recognizing numerous habits helps a mineralogist identify a large number of minerals. Some habits are distinctive of certain minerals, but most minerals exhibit differing habits that are influenced by certain factors. Crystal habit may mislead the inexperienced person, as a mineral's crystal system can be hidden or disguised.

Factors influencing a crystal's habit include: a combination of two or more forms; trace impurities present during growth; and growth conditions, such as heat, pressure, and space available for growth. Minerals belonging to the same crystal system do not necessarily exhibit the same habit.

Some habits of a mineral are unique to its variety and locality. For example, while most sapphires form elongate, barrel-shaped crystals, those found in Montana form stout, tabular crystals. Ordinarily, the latter habit is seen only in ruby. Sapphire and ruby are both varieties of the same mineral, corundum.

Sometimes, one mineral may replace another, while preserving the original mineral's habit. This process is called pseudomorphous replacement. A classic example is tiger's eye quartz, in which silica replaces crocidolite asbestos. Quartz typically forms euhedral (well-formed), prismatic (elongate, prism-like) crystals, but in the case of tiger's eye, the original, fibrous habit of crocidolite is preserved.

List of crystal habits

| Habit: | Description: | Example: |

| Acicular | Needle-like, slender and/or tapered | Rutile in quartz |

| Amygdaloidal | Almond-shaped | Heulandite |

| Anhedral | Poorly formed, external crystal faces not developed | Olivine |

| Bladed | Blade-like, slender and flattened | Kyanite |

| Botryoidal or globular | Grape-like, hemispherical masses | Smithsonite |

| Columnar | Similar to fibrous: Long, slender prisms often with parallel growth | Calcite |

| Coxcomb | Aggregated flaky or tabular crystals closely spaced. | Barite |

| Dendritic or arborescent | Tree-like, branching in one or more directions from central point | Magnesite in opal |

| Dodecahedral | Dodecahedron, 12-sided | Garnet |

| Drusy or encrustation | Aggregate of minute crystals coating a surface | Uvarovite |

| Enantiomorphic | Mirror-image habit and optical characteristics; right- and left-handed crystals | Quartz |

| Equant, stout, stubby or blocky | Squashed, pinnacoids dominant over prisms | Zircon |

| Euhedral | Well-formed, external crystal faces developed | Spinel |

| Fibrous or columnar | Extremely slender prisms | Tremolite |

| Filiform or capillary | Hair-like or thread-like, extremely fine | Natrolite |

| Foliated or micaceous | Layered structure, parting into thin sheets | Mica |

| Granular | Aggregates of anhedral crystals in matrix | Scheelite |

| Hemimorphic | Doubly terminated crystal with two differently shaped ends. | Hemimorphite |

| Mamillary | Breast-like: intersecting large rounded contours | Malachite |

| Massive or compact | Shapeless, no distinctive external crystal shape | Serpentine |

| Nodular or tuberose | Deposit of roughly spherical form with irregular protuberances | Geodes |

| Octahedral | Octahedron, eight-sided (two pyramids base to base) | Diamond |

| Plumose | Fine, feather-like scales | Mottramite |

| Prismatic | Elongate, prism-like: all crystal faces parallel to c-axis | Tourmaline |

| Pseudo-hexagonal | Ostensibly hexagonal due to cyclic twinning | Aragonite |

| Pseudomorphous | Occurring in the shape of another mineral through pseudomorphous replacement | Tiger's eye |

| Radiating or divergent | Radiating outward from a central point | Pyrite suns |

| Reniform or colloform | Similar to mamillary: intersecting kidney-shaped masses | Hematite |

| Reticulated | Acicular crystals forming net-like intergrowths | Cerussite |

| Rosette | Platy, radiating rose-like aggregate | Gypsum |

| Sphenoid | Wedge-shaped | Sphene |

| Stalactitic | Forming as stalactites or stalagmites; cylindrical or cone-shaped | Rhodochrosite |

| Stellate | Star-like, radiating | Pyrophyllite |

| Striated/striations | Surface growth lines parallel or perpendicular to c-axis | Chrysoberyl |

| Subhedral | External crystal faces only partially developed | |

| Tabular or lamellar | Flat, tablet-shaped, prominent pinnacoid | Ruby |

| Wheat sheaf | Aggregates resembling hand-reaped wheat sheaves | Zeolites |

Uses of crystals

Historically, gemstones, which are natural crystals, have been sought after for their aesthetic appeal. In addition, they have been said to possess healing properties. Crystals (both natural and synthetic) also have a variety of practical applications, some of which are noted below.

- Solid-state laser materials are often made by doping a crystalline solid with appropriate ions. For example, the first working laser was made from a synthetic ruby crystal (chromium-doped corundum). Also, titanium-doped sapphire (corundum) produces a highly tunable infrared laser.

- Mica crystals, which are excellent as electrical insulators, are used in the manufacture of capacitors and insulation for high-voltage electrical equipment.

- Based on their extreme hardness, diamonds are ideal for cutting, grinding, and engraving tools. They can be used to cut, polish, or wear away practically any material, including other diamonds.

- Quartz crystals, which have piezoelectric properties, are commonly used to make "oscillators" that keep track of time in wristwatches, provide a stable clock signal for digital integrated circuits, and stabilize radio transmitter frequencies.

See also

Notes

External links

All links retrieved May 5, 2022.

- Crystallographic Teaching Pamphlets – International Union of Crystallography

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Crystal history

- Crystallization history

- Crystal_structure history

- Crystal_habit history

- Crystallite history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 06:03:38 | 183 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Crystalline | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF