Epistle To The Hebrews

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia See also Mystery:Did Jesus Write the Epistle to the Hebrews?

The Epistle to the Hebrews is one of the greatest mysteries in all of intellectual history: the authorship of this brilliant work is unknown, and was certainly not Saint Paul. It contains much Biblical scientific foreknowledge, such as foreshadowing the Second Law of Thermodynamics by explaining that the "universe" shall "wear out" like a "garment", i.e., entropy is always increasing.[1] This book is the only one to state that Jesus was tempted in every way possible "as we are,"[2] and only this book explains Jesus's relationship to angels,[3] picking up on the discussion at Luke 24:23 (Road to Emmaus). This Epistle may have inspired the Gospel of Luke.

This Epistle was written perfectly at the highest level of the Greek language. "It would be difficult to find anywhere passages more exact and pregnant in expression than i. 1-4; ii. 14-18; vii, 26-28; xii, 18-24."[4] This short book demonstrates a phenomenal knowledge of scriptures, and draws an analogy between the new concept of Christian faith and the sacrifice of Isaac in the Old Testament.[5][6] It contains a record number of words (154) that do not appear anywhere else in the New Testament,[7] and a striking absence of five words commonly used elsewhere. This also contains a favorite verse of athletes: "let us run with endurance the race that is set before us."[8]

This epistle is actually not a letter to the Hebrews, but a detailed explanation to everyone of the reasons behind Jesus's life and Passion, and how God did not fail to intervene as many mistakenly think. Unlike the actual letters in the New Testament, this book is not introduced by the name of its author. Its title of "Hebrews" is itself a misnomer, as the explanation in the book is plainly for everyone. The only hint we have about its author is Hebrews 13:19, where the author urges the audience to pray "in order that I [i.e., Jesus] may be restored to you the sooner."[9]

This Epistle, the nineteenth book of the New Testament, was likely written soon after Jesus's Resurrection, because it implies that none of the disciples have shed blood yet (Hebrews 12:4 ), and refers to worship practices under the old covenant in the present tense (Hebrews 8:4-5 , Hebrews 10:1-3 ).[10]

This Epistle contains an admonition against both same-sex "marriage" and adultery: "Let marriage be held in honor among all, and let the marriage bed be undefiled, for God will judge the sexually immoral and adulterous."[11]

Luke's Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles, particularly its chapter 7, apparently benefited from having a copy of this Epistle because Luke imitated it in several ways.[12] This Epistle was written before institution of the Eucharist and before the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in A.D. 70.[13] This Epistle was also known to Clement, a very early pope, as confirmed by 1 Clement (17:1, 36:2-5), which is typically dated as having been written sometime between A.D. 95 and 120.[14] There are striking similarities between this Epistle and Luke's work, which suggests that one inspired the other. Given that this Epistle is written at a higher level and probably earlier than Luke's works, this Epistle probably inspired Luke to write his Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles.

Chapter 11 of this epistle is known as the "Hall of Faith."[15] The phrase "brotherly love" — Greek for "Philadelphia" — originated with Hebrews 13:1 and was then repeated in various forms in Romans 12:10; 1 Thessalonians 4:9; 1 Peter 1:22; 2 Peter 1:7; 1 Peter 2:17; 1 Peter 3:8; 1 John 3:10, 4:7, and 4:20-21, which further demonstrates that the Epistle to the Hebrews was written first.

Chapter 12 begins with one of the most inspiring verses for athletes: "And let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us."[16]

Contents

Language[edit]

The Greek of his Epistle is extraordinarily sophisticated, and is widely regarded as the best example in the New Testament,[17] This Epistle is noted for its "striking purity and elegance."[18] Not only does the author show "great familiarity with the rules of the Greek literary language" but also "of all the New Testament authors he has the best style. His writing may even be included among those examples of artistic Greek prose whose rhythm recalls the parallelism of Hebrew poetry."[19] Even in the English translation, the language is refined and sophisticated. It uses 168 terms which appear in no other part of the New Testament, including ten words found neither in koine or classical Greek, and a further forty words which do not appear in the Septuagint.

The Epistle's length is 4953 words in English, which would take about 90 minutes to recite in Greek, including pauses and questions, because Greek has more syllables per the corresponding English word. Jerusalem is about 6.5 miles from Emmaus, but Jesus joined the pair outside of Jerusalem and they ended this dialog outside of Emmaus, so it was roughly only a 6-mile distance, or about 90 minutes when walked briskly to avoid impending darkness (15 minutes per mile). In other words, the length of this Epistle matches perfectly the length of the presentation by Jesus while walking from Jerusalem to Emmaus, as described in Luke 24:13-35.

Author[edit]

The identity of the author of the epistle has been called "the riddle of the New Testament."[20] It remains the only New Testament book whose authorship is definitely unknown. The earliest translations of the King James Bible call it "the Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Hebrews," but this is implausible conjecture, and also a position that was not adopted by the church until the Middle Ages. By the time of the Reformation, this authorship was being questioned. While commonly attributed to Paul, a comparison of the language and style with his other writings demonstrate that he was not the author, although the ideas expressed within it do not contradict Pauline thought, suggesting that the author may have been a pupil of his.

The strikingly beautiful and sophisticated use of the Greek language in this book suggests it was written by a great Greek thinker, perhaps someone at the high level of Aristotle or Plato.

Attridge[21] writes: "Although Hebrews is included in the Pauline corpus and was part of that corpus in its earliest attested form ([eg papyrus] P46), it is certainly not a work of the apostle. This fact was recognized, largely on stylistic grounds, even in antiquity. Some patristic authors defended the traditional Pauline attribution with theories of scribal assistants such as Clement of Rome or Luke, but such hypotheses do not do justice to the very un-Pauline treatment of key themes, particularly those of law and faith. Numerous alternative candidates for authorship have been proposed. The most prominent have been Barnabas, to whom Tertullian assigned the work; Apollos, defended by Luther and many moderns; Priscilla, suggested by von Harnack; Epaphras; and Silas. Arguments for none are decisive, and Origen's judgment that "God only knows" who composed the work is sound."

Wikipedia acknowledges that this short book is a masterpiece and its authorship is a mystery. Wikipedia speculates about possible authors, and yet omits any mention of Jesus as a possibility.[22] The author of this Epistle was certainly a man based on its Greek syntax,[23] and yet Wikipedia's lead suggestion for who wrote it is the woman Priscilla.

Provenance[edit]

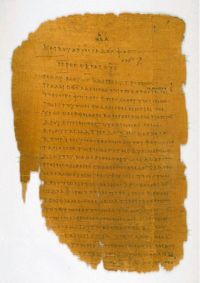

The earliest copy in existence is part of a papyrus codex in Greek of the Letters of Saint Paul, dating from around A.D. 200. The codex, referred to as P46 was discovered in 1931, and provided a text at least a century older than the Vatican and Sinaitic codices, the oldest authorities on which the text had previously rested.[24] The epistle can be dated with some certainty by its content: the use of "Remember your leaders, who spoke the word of God to you. Consider the outcome of their way of life and imitate their faith" (Heb 13:7) is consistent with a period shortly after the Passion. The epistle also discusses the temple and its sacrifices in the present tense: this places its writing prior to the destruction of the temple in A.D. 70.

To whom written[edit]

It is uncertain to whom the letter was sent, bearing only the words "to the Hebrews," and it has been variously suggested that it was sent to the church at Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem or Ephesus. Pawson[25] points to the ending of the letter (which was surely added later): "Those from Italy send you their greetings" (Heb 13:24) as indicating the letter was written to Italy, most likely the church in Rome. In light of its title, which was also likely added later,[26] the "letter" may have been specifically meant for that portion of the church that was Jewish. This becomes even more apparent, given the date of the letter, when one considers the events that were taking place in Rome at this time. Under Claudius, many Jews had been banished from Rome, including Priscilla and Aquila who had escaped to Corinth. The church in Rome became largely made up of Gentiles, and as a result, when the Jews began to return in AD 54 after Claudius' death, there was a significant tension between Jewish and Gentile believers. (See Messianic Judaism.) Nero ascended to the imperial throne after Claudius, and it was under his rule that the church entered a great period of suffering. The early Christians in particular were singled out for persecution, and many were executed during this time.

While Paul's Epistle to the Romans makes no mention of this, the epistle to the Hebrews does discuss the persecution, including the vandalism of their homes and even imprisonment, and Timothy is mentioned as one of the believers who has been imprisoned. However, there is no mention of martyrs at this time, which further cements the epistle to a definite time around the middle of Nero's reign. The treatment being endured by the church explains the point of the epistle: those members who were Jews could easily escape from the persecution by publicly denying faith in Jesus Christ and returning to Judaism, which at this time was still legal, while Christianity was not. The letter, then, seems to have been written from Jerusalem, probably by a Jewish believer who was a pupil of Paul, addressed specifically to the Jewish members of the church in Rome, as an exhortation to remain firm within the church.

Structure and content[edit]

The entire Letter to the Hebrews constitutes a flawlessly-reasoned and impassioned argument against committing apostasy. The epistle is both letter and sermon and seems to have been intended to be read in Christian meetings as a sermon. Read as such, it would take around 45 minutes. Chapters 1-10 of the epistle quite clearly emphasize the contrast between the Old and New Testaments and between Judaism and Christianity, and the superior position that the believers are in through having the "Son of God" as their mediator rather than angels, the mere servants of God. The opening of chapter 1 is regarded by most scholars as the finest Greek in the New Testament in terms of its construction, rhythm and sheer beauty, more so even than the more famous passages of Genesis 1:1 and John 1:1:God, who at sundry times and in divers manners spake in time past unto the fathers by the prophets, Hath in these last days spoken unto us by his Son, whom he hath appointed heir of all things, by whom also he made the worlds; Who being the brightness of his glory, and the express image of his person, and upholding all things by the word of his power, when he had by himself purged our sins, sat down on the right hand of the Majesty on high: Being made so much better than the angels, as he hath by inheritance obtained a more excellent name than they. (Heb 1:1-4)

The epistle deals significantly with how the Old and New Testaments relate to each other, and meet at the death - the sacrifice - of Jesus. Because of this, it has provided the basis for most interpretative models for Christian understanding of the Old Testament. From the epistle come the concepts:

- the "old" sacrifices had to be repeated - the sacrifice of Jesus is once and everlasting

- the old priests are now no longer required - Jesus as the one High Priest of the order of Melchizedek has replaced them all

- the old sanctuary had its closed tabernacle - the new sanctuary has its open throne: all are able to enter the Holy of Holies through Jesus as mediator between man and God.

The writer uses the allusion of "substance and shadows" - while the shadow of Jesus is written throughout[27] the Old Testament, now the substance has been shown to the people. The epistle is supremely Christ-centered, and it is the only book of the Bible which focuses on his priesthood and his "present" work as intercessor - leading to some scholars to describe it as the "Fifth Gospel" because of its emphasis on His work in the present.[28]

Chapter 11 of the epistle concentrates on faith, and looks back to the great heroes of faith in the Old Testament, using them to inspire and to act as models. Also, there are warnings about losing faith and "backsliding". The warnings are severe, and describe two stages: drifting away, neglecting fellowship with other believers and neglecting faith; and willful, deliberate apostasy and the denial of Jesus. Fellowship is rightly magnified by the epistle, given the circumstances in which it was written and first meant to be read. It emphasizes that there is safety in fellowship, and that the devil will pick off Christians on their own. When being persecuted, it is important to focus on Jesus, and look to the church "family" for comfort - this message remains as valid for Christians today as it was for the early church under the persecution of Nero (10:25 is a common verse used to inform Christians that church attendance should not be forsaken).

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Hebrews 1:10-11.

- ↑ Hebrews 4:15 (ESV).

- ↑ Hebrews 1:4,5,6,7, and 13.

- ↑ The Epistle to the Hebrews: The Greek Texts with Notes and Essays (edited by Brooke Foss Westcott), xlvi

- ↑ Saldarini, Anthony J. Epistle to the Hebrews Believe. Accessed 15 March 2008

- ↑ Pawson, J. David Unlocking The Bible p.1113 (London, Collins; 2003) ISBN 978 0 00 716666 4

- ↑ https://www.neverthirsty.org/bible-qa/qa-archives/question/how-any-words-are-in-the-greek-new-testament/

- ↑ Hebrews 12:1

- ↑ ESV quoted here.

- ↑ Compare Hebrews 10:32-34 and Acts 8:1-3. It is not impossible that this Epistle could also have been written at any time during those 37 years, even as late as February A.D. 70 (A.D. 33 + 37 years = A.D. 70). The Temple was taken in March of that year and burned in August. See the following historical documentation.

- War, Book 5 (biblestudytools.com)

War, Book 6 (biblestudytools.com) - Wars between the Jews and Romans: the destruction of Jerusalem (70 CE) (livius.org)

- First Jewish-Roman War: Siege of Jerusalem, J. E. Lendon, associate professor of history at the University of Virginia. (historynet.com)

- Josephus: The Essential Writings A Condensation of Jewish Antiquities and The Jewish War, Translated and Edited by Paul L. Maier, © 1988, Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel, Inc. P.O. Box 2607, Grand Rapids, MI 49501

Eusebius—The Church History: A New Translation with Commentary Copyright © 1999 by Paul Maier, Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel Inc., P.O. Box 2607, Grand Rapids, MI 49501

- War, Book 5 (biblestudytools.com)

- ↑ Hebrews 13:4 (ESV)

- ↑ "Lukan Authorship of Hebrews," by David Lewis Allen, pp. 143-50, which describes the parallels between Acts 7 and Hebrews 11.

- ↑ http://www.mycrandall.ca/courses/ntintro/Heb.htm

- ↑ Theopedia says that Clement cited the Epistle to the Hebrews in A.D. 96. [1]

- ↑ HEBREWS 11 – EXAMPLES OF FAITH TO HELP THE DISCOURAGED

- ↑ Hebrews 12:1

- ↑ Pawson, J. David op cit

- ↑ "Language and style" Epistle to the Hebrews Catholic Encyclopedia. Accessed 15 March 2008

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia op cit (emphasis added).

- ↑ Scott, E. F. The Epistle of the Hebrews: Its Doctrine and Significance (Edinburgh; T and T Clarke; 1922) full text online. Accessed 15 March 2008

- ↑ Attridge, Harold W. Epistle to the Hebrews Anchor Bible Dictionary

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Authorship_of_the_Epistle_to_the_Hebrews

- ↑ https://www.biblicalfoundations.org/an-introduction-to-hebrews-who-is-the-author/

- ↑ From Papyri to King James: The Transmission of the English Bible University of Michigan. Accessed 15 March 2008

- ↑ Pawson, J. David op cit p.1115

- ↑ http://www.bible.ca/ef/expository-hebrews-1-1-2-18.htm

- ↑ Hodgkin, A. M. Christ in All the Scriptures (Westwood, NJ; Barbour and Co. Inc; 1989) full text online. Accessed 16 March 2008

- ↑ Pawson, J. David, op cit p.1142

External links[edit]

- A fantastic analysis of authorship

- Hebrews - A Defense of Christian Faith - The Study of Hebrews: Ladies Bible Class, 2 January - 27 March 2001. West-Ark Church of Christ, Fort Smith, Arkansas/Women In God's Service

- Commentary By Saint Thomas Aquinas On the Epistle to the Hebrews - full text online

- John Calvin: Commentary on Hebrews - full text online

- A course on the Epistle to the Hebrews

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

Categories: [New Testament Books] [Homosexuality] [Deuterocanonical Books of the New Testament]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/11/2023 06:10:02 | 27 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Epistle_to_the_Hebrews | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF