Saint Paul

From Nwe

From Nwe Paul of Tarsus (originally Saul of Tarsus), also known as Saint Paul or The Apostle Paul, (4–64 C.E.) is widely credited with the early development and spread of Christianity. His missionary and theological efforts propagated the new faith beyond the confines of Judaism to take root among Gentiles (non-Jews) and become a universal religion. Many Christians view him as the first theologian and chief interpreter of the teachings of Jesus. The Epistles attributed to him in the New Testament, seven of which are regarded by scholars as genuine, are a primary source of Christian doctrine.

Saul is described in the New Testament as a Hellenized Jew and Roman citizen from Tarsus (present-day Turkey), who before his conversion was a great persecutor of Christians. His experience on the road to Damascus brought about Saul's conversion to the religion (Acts 9:3-19; 22:6-21; 26:13-23), after which he took the name Paul. His conversion was also a commission to become the "apostle to the Gentiles" (Romans 11:13, Galatians 2:8). Thereupon Paul traveled throughout the Hellenistic world, founding churches and maintaining them through his letters, or Epistles, which later became part of the New Testament.

Paul is venerated as a saint in the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran and Anglican churches. Nearly all Christians accept his teachings as the core of Christian doctrine. As a missionary who braved many obstacles, who faced imprisonment and death for the sake of his faith in Jesus Christ, he remains a model of dedication, zeal, faithfulness and piety.

Due to his teachings and their influence on the development of Christianity, some modern scholars consider him the founder of Christianity as a distinct religion. By liberating Christianity from the strictures of the Mosaic Law and replacing it with a universal ethic rooted in the spirit of Christ, Paul transformed Christianity into a universal religion, whereas the religion of Jesus and his earliest disciples had been in many respects a branch of Judaism.

In modern times, Paul has become a lightning-rod for radical theories about Christianity. Anyone who wishes to reassess the Jewish-Christian relationship must at some point come to terms with his thought.

Paul's Writings and Writings about Paul

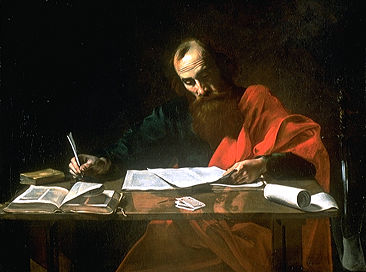

Paul wrote a number of letters to Christian churches and individuals. However, not all have been preserved; 1 Corinthians 5:9 alludes to a previous letter sent by him to the Christians in Corinth that has been lost. Those letters that have survived are part of the New Testament canon, where they appear in order of length, from longest to shortest:

- Epistle to the Romans (Rom.)

- First Epistle to the Corinthians (1 Cor.)

- Second Epistle to the Corinthians (2 Cor.)

- Epistle to the Galatians (Gal.)

- Epistle to the Philippians (Phil.)

- First Epistle to the Thessalonians (1 Thess.)

- Epistle to Philemon (Philem.)

Three more letters that were traditionally attributed to Paul are now generally believed to have been written by his followers some time in the first century. They are called the Deutero-Pauline Epistles because at least in theology and ethics they generally mirror Paul's views:

- Epistle to the Ephesians (Eph.)

- Epistle to the Colossians (Col.)

- Second Epistle to the Thessalonians (2 Thess.)

A third group of letters traditionally attributed to Paul, the Pastoral Epistles, regard matters of church order from the early second century. They have little in common with the historical Paul:

- First Epistle to Timothy (1 Tim.)

- Second Epistle to Timothy (2 Tim.)

- Epistle to Titus (Titus)

Paul certainly did not write the Epistle to the Hebrews, although some traditions ascribe the book to him. Extensive biographical material about Paul can be found in Acts of the Apostles.

There is also the apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla. However, scholars usually dismiss this as a second century novel.

Textual issues in studying Paul's life

What we know about Paul comes from two sources: Paul's own letters and the Acts of the Apostles, which at several points draws from the record of an eyewitness. However, both sources have weaknesses: Paul's letters were written during a short period of his life, between 50 and 58 C.E.; while the author of Acts makes a number of statements that have drawn suspicion—for example, the claim that Paul was present at the death of Saint Stephen (Acts 7:58). Traditionally, Acts has been regarded as an historically accurate document because it was written by Luke (the same writer who wrote the Gospel of Luke). However, the scholarly consensus is that Luke-Acts was written around 85 C.E., a generation after Paul's death. As the Book of Acts may be giving an idealized account of the church's beginnings, its stories about historical personages may be historically unreliable.

Because of the problems with the two primary sources, as Raymond E. Brown (1998) explains, historians take one of three approaches:

- the traditional approach is to completely trust the narrative of Acts, and fit the materials from Paul's letters into that narrative;

- the approach used by a number of modern scholars, which is to distrust Acts; sometimes entirely; and to use the material from Paul's letters almost exclusively; or

- an intermediate approach, which treats Paul's testimony as primary, and supplements this evidence with material from Acts.

The following construction is based on this fourth approach. There are many points of scholarly contention, but this outline reflects an effort to trace the major events of Paul's life.

Early life

Paul was born as Saul in Tarsus in Cilicia. He received a Jewish education in the tradition of the Pharisees, and may have even had some rabbinical training. Thus he described himself as "an Israelite of the tribe of Benjamin, circumcised on the eighth day… as to the law a Pharisee" (Philippians 3:5), and of the Judaism, "more exceedingly zealous of the traditions" (Galatians 1:14). Yet growing up in Tarsus, a city that rivaled Athens as an educational center, Paul also imbibed Hellenistic culture. His letters show he had a formal Greek education, for he wrote in elegant Greek. Thus he was raised in two worlds: in a proud Jewish family that maintained its Jewish heritage and the Hellenistic world of the Greek city. The tradition in Acts 22:3, that he studied under Gamaliel, a famous rabbi of the time, is supported by the rabbinical techniques that he uses in crafting the arguments in his letters. Gamaliel I was the grandson of Hillel, a teacher renowned for his broad-minded and tolerant approach to Judaism.[1]

Nothing is known of Paul's family. It is highly unlikely that Paul's salutation in Romans 16:3 to Rufus and to "his mother and mine" meant that he had a brother named Rufus; most scholars take it merely an expression of affection for a woman who treated Paul as a son. He wrote, "To the unmarried and the widows I say that it is well for them to remain unmarried as I am." (1 Corinthians 7:8); on this basis Roman Catholics traditionally have held that Paul was celibate his entire life. Still, Paul writes sensitively about married life (1 Corinthians 7:3-16). Moreover, it was the custom of the Jews of Paul's time, and of Pharisees in particular, to marry young in accordance with the commandment to "be fruitful and multiply" (Genesis 1:28). As Paul had been an observant Jew until his conversion (30-33 C.E.) when he was over thirty years of age, he most likely had been married, and by the beginning of his ministry he was either widowed or divorced.

Paul supported himself during his travels and while preaching—a fact he alludes to a number of times (1 Corinthians 9:13–15); according to Acts 18:3 he worked as a tentmaker—a reputable and skilled craft in those days. He also found support among the Christian community, especially wealth widows who ran house churches in various cities. According to Romans 16:2 he had a patroness (Greek prostatis) named Phoebe.[2]

Acts 22:25 and 27–29 also state that Paul was a Roman citizen—a privilege he used a number of times to defend his dignity, including appealing his conviction in Iudaea Province to Rome. This was not unusual; since the days of Julius Caesar, Rome had opened a path to citizenship to prominent families throughout the Empire.

Conversion and early ministry

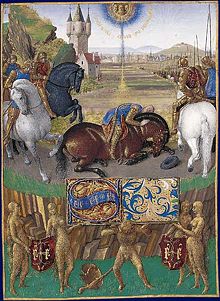

Paul himself admits that he at first persecuted Christians (Phil. 3:6) but later embraced the belief that he had fought against. Acts 9:1–9 memorably describes the vision Paul had of Jesus on the road to Damascus, a vision that led him to dramatically reverse his opinion. Paul himself offers no clear description of the event in any of his surviving letters; and this, along with the fact that the author of Acts describes Paul's conversion with subtle differences in two later passages, has led some scholars to question whether Paul's vision actually occurred. However, Paul did write that Jesus appeared to him "last of all, as to one untimely born" (1 Corinthians 15:8), and frequently claimed that his authority as "Apostle to the Gentiles" came directly from God (Galatians 1:13–16). In addition, an adequate explanation for Paul's conversion is lacking in the absence of his vision. Acts 9:5 suggests that he may have had second thoughts about his opposition to Jesus' followers even before the Damascus Road experience, which has become synonymous with a sudden, dramatic conversion or change of mind.

Following his conversion, Paul first went to live in the Nabataean kingdom (which he called "Arabia") for three years, then returned to Damascus (Galatians 1:17–20) until he was forced to flee from that city under the cover of night (Acts 9:23–25; 2 Corinthians 11:32 ff.). He traveled to Jerusalem, where he met Peter, who was already the leader of the Christian movement, and with James the brother of Jesus (Galatians 1:18-19). He then returned to his native district of Cilicia (of which Tarsus was the capital) and to his base in neighboring Syria, to carry on missionary activity (Galatians 1:21).

While in Syria, Paul joined up with Barnabas, a leader of the church in Antioch, which became his base of operations. Antioch, the capital of the Roman province of Syria, was the third city in the Roman Empire after Rome and Alexandria, and a cultural crossroads. This is where Paul's Hellenistic form of Christianity would flourish and spread throughout the empire. According to Acts, "in Antioch the disciples were for the first time called Christians" (11:26).

There is some discrepancy as to what happened next. According to the Book of Acts, Paul left Antioch and travelled through Cyprus and southern Asia Minor to preach of Christ—a labor that has come to be known as his "First Missionary Journey" (Acts 13:13, 14:28). After its success, Paul traveled a second time to Jerusalem and appeared at the Council there (Acts 15). Paul's letters, on the other hand, seem to indicate that Paul stayed in the region of Tarsus and Antioch until the Council at Jerusalem, which may have been occasioned by his success there. Reconstructing Paul's life from his letters, he most likely began his wider missionary endeavors based on the commission he received at the Council.[3]

Acts describes three missionary journeys; they are considered the defining actions of Paul. For these journeys, Paul usually chose one or more companions for his travels. Barnabas, Silas, Titus, Timothy, Mark, Aquila and Priscilla all accompanied him for some or all of these travels. He endured hardships on these journeys: he was imprisoned in Philippi, was lashed and stoned several times, and almost murdered once. Paul recounts his tribulations:

"Five times I have received at the hands of the Jews the forty lashes less one. Three times I have been beaten with rods; once I was stoned. Three times I have been shipwrecked; a night and a day I have been adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from robbers, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brethren; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, in hunger and thirst, often without food, in cold and exposure." (2 Cor. 11:24–27).

The Jerusalem Council

About 49 C.E., after 14 years of preaching, Paul traveled to Jerusalem with Barnabas and Titus to meet with the leaders of the Jerusalem church—namely James, Peter, and John; an event commonly known as the Council of Jerusalem. The issue for the Council was whether Paul's innovative teachings aimed at non-Jewish Christians, teaching them that their salvation did not require obedience to the Law of Moses, could be reconciled with the traditions of the mother church in Jerusalem, which was composed of predominantly Jewish-Christians. Should a non-Jew who accepted Jesus Christ be required to accept Judaism as a precondition? Or could one be a Christian apart from being a Jew? On the other hand, if non-Jews could directly receive Christ, did that mean that Jewish believers were freed from the need to obey Mosaic Law (see Antinomianism)?

Here the account in Acts 15 and Paul's own account in Galatians 2:1-10 come at things from different angles. Acts states that Paul was the head of a delegation from the church of Antioch that came to discuss whether new converts needed to be circumcised. If so, this would mean that all Christians should observe the Jewish law, the most important being the practice of circumcision and dietary laws. This was said to be the result of men coming to Antioch from Judea and "teaching the brothers: 'Unless you are circumcised, according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved'" (Acts 15:1).

Paul in his account in Galatians states that he had attended "in response to a revelation [to] lay before them the gospel... [he] preached among the Gentiles" (Gal. 2:2), "because of false brethren secretly brought in, who slipped in to spy out our freedom which we have in Christ Jesus, that they might bring us into bondage" (Gal. 2:4). He states (in Gal. 2:2) that he wanted to make sure what he had been teaching to the Gentile believers in previous years was correct. The result was a bifurcation of mission: Peter and James would lead the Jewish Christians as they had been—to believe in Jesus while keeping their Jewish faith, while Paul was endorsed with the mission to spread "the gospel to the uncircumcised. (Gal. 2:7-10)

The verdict of the Council in Acts 15 reveals that Peter and James understood Paul's work within the parameters of the Mosaic Law; specifically, the Noachide Laws which the rabbis held were required of non-Jews for them to be deemed righteous. This view was put forth by James (Acts 15:20-21), and it became the verdict of the Council. They sent a letter accompanied by some leaders from the Jerusalem church back with Paul and his party to confirm that the Mosaic Law should not overburden the Gentile believers beyond abstaining from food sacrificed to idols, from blood, from the meat of strangled animals, and from sexual immorality (Acts 15:29). The Council did not hold that the Mosaic Law was non-binding on Gentile Christians, only that they fell into the category of "righteous Gentiles" for which the Law's requirements were minimal.

Meanwhile, Jewish believers were still expected to be observant. A rumor that Paul aimed to subvert the Law of Moses is cited in Acts 21:21, however, according to Acts, Paul followed James' instructions to show that he "kept and walked in the ways of the Law." Yet from his own teachings, apparently Paul did not regard the Mosaic Law as essential or binding in the slightest. For instance, regarding the Noachide law not to eat food offered to idols, he observes it only as expedient so as not to damage those weak in faith (1 Corinthians 8). Ultimately, the Pauline view that justification is entirely by the grace of Christ and is in nowise by works of Law is incompatible with the Jewish Noachide principle, which still gives pride of place to Jews as those who observe the entire Law.

Despite the agreement they achieved at the Council, Paul recounts how he later publicly berated Peter, accusing him of hypocrisy over his reluctance to share a meal with Gentile Christians because some Jewish Christians were present (Gal. 2:11–18). Despite Paul's assertion that all Christians, whether Jew or Greek, were "one in Christ Jesus (Gal. 3:28), some Jewish-Christians still regarded themselves as set apart by their observance of the Law and looked down upon non-Jewish Christians as less perfect in their faith. These were the "Judaizers" who plagued Paul's ministry.

After his return from Jerusalem, Paul began his major work as a missionary. This is what the Book of Acts calls his Second Missionary Journey; however from Paul's letters scholars surmise that the three missionary journeys described in Acts is an idealization, that in fact his travels cannot be so neatly distinguished. During this period of six to eight years, Paul traveled West through Asia Minor, stopping for a time in Ephesus. Then he continued west into Greece, where he lived for some years in Corinth. It was during this period that Paul wrote most of his Epistles that are found in the New Testament.

Founding of churches

Paul spent the next few years traveling through western Asia Minor—this time entering Macedonia—and founded his first Christian church in Philippi, where he encountered harassment. Paul himself tersely describes his experience as "when we suffered and were shamefully treated" (1 Thess. 2:2); the author of Acts, perhaps drawing from a witness (this passage follows closely on one of the "we passages"), explains here that Paul exorcised a spirit from a female slave—ending her ability to tell fortunes and thus reducing her value—an act the slave's owner claimed was theft, wherefore he had Paul briefly put in prison (Acts 16:22). Paul then traveled along the Via Egnatia to Thessalonica, where he stayed for some time, before departing for Greece. First he came to Athens, where he gave his legendary speech in Areopagus (Areios Pagos) and said he was talking in the name of the Unknown God who was already worshiped there (17:16–34). He next traveled to Corinth, where he settled for three years, and wrote the earliest of his surviving letters, the first epistle to the Thessalonians (1 Thessalonians).

Again, Paul ran into legal trouble in Corinth: on the complaints of a group of Jews, he was brought before the proconsul Gallio, who decided that it was a minor matter not worth his attention and dismissed the charges (Acts 18:12–16). From an inscription in Delphi that mentions Gallio, we are able to securely date this hearing as having occurred in the year 52 C.E., providing a secure date for the chronology of Paul's life.

Following this hearing, Paul continued his preaching (usually called his Third Missionary Journey), traveling again through Asia Minor and Macedonia, to Antioch and back. He caused a great uproar in the theater in Ephesus, where local silversmiths feared loss of income due to Paul's activities. Their income relied on the sale of silver statues of the goddess Artemis, whom they worshipped, and the resulting mob almost killed him (19:21–41). As a result, when he later raised money for victims of a famine in Judea and his journey to Jerusalem took him through the province once again, he carefully sailed around Ephesus—instead summoning his followers to meet him in Miletus (20:17–38).

Paul's leadership

Paul's role as a leader within the early Christian community can be understood as deriving from his commission to preach the Gospel to the Gentiles (non-Jews), which was recognized by the Church at Antioch when it set him and Barnabas aside for this work (Acts 13:2-4). Paul considered the commission to preach to non-Jews to be his particular calling (I Timothy 2:3).

Paul claimed and appears to have been afforded the title of Apostle. The Apostles had known and followed Jesus during his life and exercised a special leadership in the church but Paul's claim to this office was based on his encounter with the Risen Jesus. He himself emphasized that he has been 'called' by God, not by men (Gal. 1:1) and because he had persecuted the Church, he describes himself as the “least of all the apostles” (Eph. 3:8-9). In Galatians, he appears anxious to establish that following his conversion he had met with the senior apostles, Peter and James (the Lord's brother), although not with all of the apostles, and that they had accepted his bone fides (Galatians). This could reflect criticism that he was not a legitimate Apostle and lacked the authority that was recognized as peculiarly theirs. Traditionally, Paul is seen as second in authority only to Peter.

Some scholars identify a tension or struggle for leadership between Peter and James on the one side, and Paul on the other, represented by the Jerusalem Council. However, the matter discussed in the council concerned the question of whether Gentile Christians ought to become Jews. The compromise that was reached on that issue also affirmed Paul's leadership of the missions to the Gentiles, even as it also affirmed the primacy of Peter, James and the Jerusalem Church over the entire body of believers.

The far-sighted leaders of the Council recognized that God was working in Paul's ministry, and accepted it for that. But some of the rank and file Jewish-Christians from the Jerusalem church traveled throughout the churches Paul founded denouncing Paul's teaching and arguing that the true Christian faith required that Gentile converts must also become observant Jews. Paul's letters indicate that he continually had to contend with these "Judaizers" (Galatians, Philippians 3:2-11). Paul himself in the beginning may have wavered on the issue, because according to Acts 16:3 he circumcised Timothy. Since these other teachers came from Jerusalem, ostensibly representing the mother church, they had an authority which rivalled that of Paul. Thus Paul in his letters, especially the two epistles to Corinthians, has to constantly assert his authority over his many rivals (1 Cor. 1:12-17; 2 Cor. 11:4-5).

Arrest, Rome, and later life

Paul's final act of charity towards the Jerusalem Church was to raise funds from the wealthier Gentile churches he had founded to help the Jewish-Christians in Jerusalem, many of whom were in dire straits. These had been requested at the Council of Jerusalem (Gal. 2:10) as part of the agreement authorizing him to lead the Gentile missions. Paul knew that despite his agreement with Peter and James, many other members of the Jerusalem church continued to oppose him for teaching that salvation in Christ was entirely apart from the Mosaic Law, which to them seemed to undermine the Law altogether. Perhaps his charity was meant to be a peace-offering, to demonstrate that despite their differences he sincerely regarded them as brothers in Christ. Furthermore, as a turncoat from the Jewish faith, Paul had earned the enmity of the Jewish establishment. In the face of opponents both inside and outside the church, when Paul returned to Jerusalem bearing gifts he may have felt like Jacob did when he was returning to see his brother Esau.

The Book of Acts, which scholars believe presents an idealized picture of Christian unity, only briefly describes the internal dissension that accompanied Paul's arrival in Jerusalem (Acts 21:21-22); mainly it blames Paul's arrest on external (non-Christian) enemies. Ananias the High Priest made accusations against him and had him imprisoned (Acts 24:1–5). Paul claimed his right, as a Roman citizen, to be tried in Rome; but owing to the inaction of the procurator Antonius Felix (52-60 C.E.), Paul languished in confinement at Caesarea Palaestina for two years until a new procurator, Porcius Festus, took office (60-62 C.E.), held a hearing and sent Paul by sea to Rome, where he spent another two years in detention (Acts 28:30).

The Book of Acts describes Paul's journey from Caesarea to Rome in some detail. The centurion Julius had shipped Paul and his fellow prisoners aboard a merchant vessel, whereon Luke and Aristarchus were able to take passage. As the season was advanced, the voyage was slow and difficult. They skirted the coasts of Syria, Cilicia, and Pamphylia. At Myra in Lycia, the prisoners were transferred to an Alexandrian vessel transporting wheat bound for Italy, but the winds being persistently contrary, a place in Crete called Goodhavens was reached with great difficulty, and Paul advised that they should spend the winter there. His advice was not followed, and the vessel, driven by the tempest, drifted aimlessly for 14 whole days, being finally wrecked on the coast of Malta. The three months when navigation was considered most dangerous were spent there, where Paul is said to have healed the father of the Roman Governor Publius from fever, and other people who were sick, and preached the gospel; but with the first days of spring, all haste was made to resume the voyage.

Acts only recounts Paul's life until he arrived in Rome, around 61 C.E.; some argue Paul's own letters cease to furnish information about his activities long before then, although others date the last source of information being his second letter to Timothy, describing him languishing in a "cold dungeon" and passages indicating he knew that his life was about to come to an end. Also, the traditional interpretation holds that Paul's letters to the Ephesians and to Philemon were written while he was imprisoned in Rome. However, modern scholars regard both 2 Timothy and Ephesians as not of Pauline authorship, while Philemon—a genuine Pauline letter—may have been written during an earlier imprisonment, perhaps at Caesarea.

We are forced to turn to church traditions for the details of Paul's final years, from non-canonical sources. One tradition, attested in 1 Clement 5:7 and in the Muratorian fragment, holds that Paul visited Spain; while this was his intention (Rom. 15:22–7), the evidence is inconclusive. A strong church tradition, also from the first century, places his death in Rome. Eusebius of Caesarea states that Paul was beheaded in the reign of the Roman Emperor Nero; this event has been dated to the year 64 C.E., when Rome was devastated by a fire.[4] One Gaius, who wrote during the time of Pope Zephyrinus, mentions Paul's tomb as standing on the Via Ostensis. While there is little evidence to support any of these traditions, there is no evidence contradicting them either, or any alternative tradition of Paul's eventual fate. It is commonly accepted that Paul died as a martyr in Rome, as did Peter.

Theological teachings

Justification by faith: Paul had several major impacts on the nature of Christian doctrine. The first was that of the centrality of faith for the Christian life, and the ability to attain righteousness (acceptance by God) through such. Paul wrote, “man is justified by faith without the deeds of the law” (Romans 3:28; see Gal. 2:16). This leads directly to the modern Protestant argument for justification by faith.

By "deeds of the law" Paul originally meant the Jewish law, as this teaching grew directly out of Paul's mission to the Gentiles, where Paul advanced it in response to the insistence by Jewish-Christians that righteousness required even non-Jewish believers to observe the Jewish law. Although the Book of Acts definitely depicts Paul as a Mosaic Law-observant Jew—for example, in Acts 16 he "personally" circumcises Timothy, even though his father is Greek, because his mother is of the Jewish faith; and in Acts 21 he defends himself against James' challenge about the rumor that he is teaching rebellion against the Law. Nevertheless, the evidence from Paul's letters is not so clear, and Acts' tendency to whitewash disputes amongst the early Christians leads us to view it with some caution. Paul made statements in his own epistles which denied the efficacy of the law altogether, and consequently numerous Christians have interpreted Paul to be anti-Law. This viewpoint found its greatest proponent in Marcion and Marcionism.

Most Protestant denominations assert that Paul's teachings constitute a definitive statement that salvation comes only by faith, and not by any external action of the believer. Beginning with Martin Luther, Protestants have generalized an argument originally advanced against the "works" of Jewish ritual law to critique any religious system that sets forth a path to salvation through human "works." Luther specifically saw in the Roman Catholic system of penances and austerities that defined the path of the monastic life a direct parallel to Jewish legalism.

Roman Catholic and Orthodox theologies dispute this view of Paul, asserting that Paul must be read alongside James, who said "faith without works is dead." Protestants respond that Paul also promoted good works—the last chapters of each of his letters are exhortations to ethical behavior—but believed that good works flow from faith. What Paul rejected was the efficacy of works apart from faith, that one could "work" one's way into heaven by good deeds.

Redemption by the cross: Paul is well known for teaching the theory of Christ's vicarious atonement as the basis of salvation. He expressed his understanding of salvation most clearly in this passage: “being freely justified by his grace through the redemption that is in Jesus Christ, whom God sent to be a propitiation through faith in his blood… for the remission of sins.” (Romans 3:24-5). The earliest Christians did not have a consistent view of salvation: some hoped for Jesus Christ's imminent return in glory when he would defeat the Romans and realize the Jewish hope of God's earthly kingdom; others hoped in the imminent resurrection; still others followed Jesus as a teacher of righteousness. Paul was among the first to teach that Jesus' death on the cross as an expiation for the people's sins, sins which they could not resolve by their own efforts. There is some evidence suggesting that Paul did not invent this concept of salvation; Philippians 2:5–11, which scholars identify as a hymn of early Christians that preexisted Paul's letter, expounds a Christology similar to Paul's. Yet it was Paul who did the most to spread this teaching, which would become the standard view of how Christians are saved.

Original Sin: Paul is the only New Testament writer to expound the doctrine of original sin. He taught the universality of sin (Romans 3:23) which stemmed from the sin of the first man, Adam (Romans 5:14-19). His transgression brought sin to all humanity, which only Jesus, the "last Adam" (1 Corinthians 15:45), could remove. Augustine of Hippo later elaborated upon Paul's teaching in his formulation of original sin. The universality of sin is answered by the universal efficacy of Christ's sacrifice.

Abraham the father of faith: Paul lifts up Abraham, who is not only the biological ancestor of the Jews, but also the ancestor of faith for all believing Christians. Thus he qualifies the exclusive claim of the Jews to be descendants of Abraham, and sets up Christianity as the new Israel. Abraham's righteousness by faith, for which he lifts up the Genesis verse "Abram believed the Lord, and he credited it to him as righteousness" (Gen. 15:6), preceded God's ordinance of ritual law (circumcision) in Genesis 17; hence, Paul argued, faith precedes works.

Teachings on the resurrection: Paul spoke of the resurrection, which he saw as the hope of all believers. "And if Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith." (1 Corinthians 15:14) He rejected crude notions of resurrection as resuscitation of the flesh from the grave. He speaks instead of the resurrection as a "spiritual body" or "glorified body" which believers will wear in the afterlife. (1 Corinthians 15:35-50). He himself looks forward to the day when he will shed his "earthly tent" to enjoy the glory of heaven and live with Christ (2 Corinthians 5:1-5).

Love: One of the most beloved passages in Paul's letters is 1 Corinthians 13, on love. He lifts love above faith, calling it "the most excellent way." Paul describes the qualities of true love in words that have never been equalled for their truth and simplicity:

- Love is patient, love is kind. It does not envy, it does not boast, it is not proud. It is not rude, it is not self-seeking, it is not easily angered, it keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth. It always protects, always trusts, always hopes, always perseveres (1 Corinthians 13:4-7).

Life in the Spirit: Paul taught that a virtuous life was the natural fruits of life in the spirit, a state of being "in Christ." The Christian does not have to work at being virtuous; rather he or she needs to be attentive to the spirit and lead a life that is spirit-led:

The fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control. Against such things there is no law. Those who belong to Christ Jesus have crucified the sinful nature with its passions and desires. Since we live by the Spirit, let us keep in step with the Spirit (Galatians 5:22-25).

Paul considered that he no longer lived but that Christ lived in him - hence the idea that trust in Jesus makes people 'new' (they are born again); he wrote, “I am crucified with Christ, nevertheless I live, yet not I but Christ lives in me, and the life I now live in the flesh I live by the faith of the Son of God, who died for me” (Galatians 2:19). A Christian comes to be "in Christ" beginning with Baptism, a rite which symbolizes dying to the old self and putting on Christ, and continuing with a life dedicated to him. As Jesus was crucified in the flesh and rose in spirit, so the Christian leaves aside his or her former life of self-seeking and sensual gratification and walks a new life in line with God and Christ (Romans 6:3-14). As long as a Christian remains faithful to the Christian walk, he can count on the Spirit of Christ to guide his way. "The mind of sinful man is death, but the mind controlled by the Spirit is life and peace" (Romans 8:6).

The cross was central to Paul's preaching. He described it as foolishness to the Greeks and as a stumbling block to Jews while for him it was the “power and wisdom of God” (1 Corinthians 1:23-24). Christ, not the Temple nor the Law, was for Paul the very center of the cosmos and that he believed that this same Christ dwelt in him, despite his continued unworthiness. According to New Testament scholar Bruce Chilton, “Deep awareness of one's self, completion by the presence of the Spirit, made devotion the deepest pleasure. As far as Paul was concerned, that was all he or anyone like him needed, and he held up that self-sufficiency… as a standard… ‘neither death nor life, neither angels nor principalities… shall be able to separate us from the love of God that is in Jesus Christ’ (Romans 8:38-39)." Chilton adds, “If you care as God cares, then Christ - the center of the entire cosmos - inhabits the recesses of that inner longing, and nothing can ever separate you from that creative passion.”[5]

Social views

Paul's writings on social issues were just as influential on the life and beliefs of Christian culture as were his doctrinal statements.

In the paranetical sections at the end of each of his letters, Paul expounds on how a follower of Christ should live a radically different life—using heavenly standards instead of earthly ones. These standards have highly influenced Western society for centuries. Paul extols the virtues of compassion, kindness, patience, forgiveness, love, peace, and gratitude. He condemns such things as impurity, lust, greed, anger, slander, filthy language, lying, and racial divisions. His lists of virtues and vices are similar to those found in the Greco-Roman literature of his day.

Paul condemned sexual immorality, saying "Flee from sexual immorality. All other sins a man commits are outside his body, but he who sins sexually sins against his own body" (1 Cor. 6:18). In this he is consistent with the moral laws of the Old Testament and the teachings of Jesus (Matthew 5:27-28; see also 1 Cor. 6:9 ff.; Eph. 5:21–33, Col. 3:1-17). Other Pauline teachings are on freedom in Christ (Gal. 5, 1 Cor. 8, Col. 2:6-23), proper worship and church discipline (1 Cor. 11), the unity of believers (1 Cor. 1:10-17, Eph. 4:1-6), and marriage (1 Cor. 7, Eph. 5:21-33). He appears to have preferred celibacy, writing that the unmarried man or woman “being free, is Christ's servant” (see 1 Cor. 8:22 and 25), although he comments that he had no direct instruction from the Lord on this issue. However, on the basis of his teaching, Christian tradition has often required its priests or ministers to be celibate.

On slavery Paul accepted the conventions of his day. Some criticize his apparent failure to explicitly condemn slavery in his Epistle to Philemon, but this may be an unfair projection from a modern vantage point, as Christian movements calling for the abolition of slavery did not begin until the late eighteenth century. Nevertheless, Paul gave pastoral encouragement to free slaves who had become believers, recognizing that despite their different social status, in a higher spiritual sense a slave and his master were brothers in Christ.

Paul was not only establishing a new cultural awareness and a society of charity, but was also subverting Roman authority through language and action. Paul used titles to describe Jesus that were also claimed by the Caesars. Augustus had claimed the titles ‘Lord of Lords,’ ‘King of Kings,’ and ‘Son of God’ (as he was the adopted son of Julius Caesar, whom he declared to be a god). When Paul refers to Jesus' life as the "Good News" (evangelion in Greek), he is using another title claimed by Augustus. Ancient Roman inscriptions had called Augustus the evangelon (good news) for Rome. Paul used these titles to expand upon the ethic of Jesus with words from and for his own place and time in history. If Jesus is lord, then Caesar is not, and so on. The ethic being that the Christian's life is not to be lived out of hope for what the Roman Empire could provide (legal, martial and economic advantage) or the pharisaical system could provide (legalistic, self-dependent salvation), but out of hope in the Resurrection and promises of Jesus. The Christianity which Paul envisioned was one in which adherents lived unburdened by the norms of Roman and Jewish society to freely follow the promise of an already established but not yet fully present Kingdom of God, promised by Jesus and instituted in his own Resurrection. The true subversive nature of Paul's ethic was not that the Church seeks to subvert the Empire (vindication in full had already been promised), but that the Church not be subverted by the Empire in its wait for Christ's return.

Paul's Teaching on the Role of Women

Many consider Paul’s views on women controversial. Paul clearly valued and recognized the ministry of women, commending several such as “Phebe our sister who is a servant of the church” (Romans 16:1) while a passage such as “in Christ there is neither male nor female” more than suggests equality (Gal. 3:28). On the other hand, he appears to have accepted the conventional subordination of women to men as part of the natural order, (1 Cor. 11:7-9) while in 1 Corinthians 14:34 he denied that women have the right to speak during Christian worship. However, other verses (such as 1 Cor. 11:5) refer to women praying and prophesying in church with the condition imposed that they cover their hair.

Some scholars believe that some of Paul's instructions about women in the Corinthian letters may have been specific advice to a particular context, not legislation for all time. They point out that Corinth was rife with pagan cultic prostitution, where alluringly dressed women played the role of priestess-prostitutes, and Paul needed to discipline the Christian church by discouraging such displays among its women. That Paul was speaking about preserving order is indicated by the context, “for God is not the author of confusion” (1 Cor. 14:33) in the immediately preceding verse). For Paul to lay permanent restrictions on women would deny the freedom about which he also wrote: “Am I not free?” (1 Cor. 9:1) while commending himself and others for exercising self-restraint.[6]

Paul's Teaching on the Jews

A Jew himself, Paul struggled with the fate of his fellow Jews who did not accept Christ. He knew first-hand their persecution of the church, and at times he too rails against them: "the Jews, who killed both the Lord Jesus and the prophets, and drove us out, and displease God and oppose all men [from salvation] by hindering us… but God's wrath has come upon them at last." (1 Thess. 2:14-16) This was certainly the all too human reaction of a man who suffered from the intolerant Jews of his day, and not meant to be a judgment for all time.

In the Book of Romans, in a more reflective moment, Paul anguished over his fellow Jews. He could not believe that God had abandoned his people, contrary to what later emerged as the traditional teaching of the Christian Church. Rather, he commended the Jews for their “zeal for God” and states that God had not “cast away his people.” Instead, once the fulness of the Gentiles has been brought into the covenant, the Jews will be grafted back onto the vine; "and so all Israel will be saved" (Romans 11:26). This is a both mystery and an eschatological act.

E. P. Sanders in his influential book Paul and Palestinian Judaism argues that the Judaism of Paul's day has been wrongly caricatured by the conventional Protestant interpretation of Paul's theology. Sanders says that it is mistaken to think that first century Judaism was a religion of "works," whereby Jews believed they had to earn their salvation by keeping the Law, and therefore when Paul spoke about "justification by faith," he was referring to a new non-works-oriented way of salvation (being declared righteous by God) announced in Christ. Sanders points out that for Jews of the first century down to the present, the Law traces out a way of holiness for the people of the covenant; it is not about performing deeds in order to accomplish salvation. Jews, rather, are justified by their being in the covenant, not by their works.

Sanders' work exposes a common Christian caricature of Judaism. Moreover, it suggests that the traditional Protestant understanding of the doctrine of justification may need rethinking.

Paul's Legacy for Christian Reform

Paul's theology has been a remarkably fertile source of ideas. His ideas, which are at some points radical and at other points conservative, have shaped Christian theology for two millennia. Paul has therefore drawn both admirers and detractors. In modern times, Paul has become a lightning-rod for radical theories about Christianity.

The dynamic theology of Paul in his letters has been a continuing source of reform and also dissent within the Christian churches. Martin Luther, John Wesley, and Karl Barth each found in Paul a primary source of theological innovation and a basis from which to critique the conventional Christian teachings of their day. Luther found in Paul the basis for the Protestant Reformation and his critique of Roman Catholic practices, notably indulgences, which appeared to him like the "works" righteousness that Paul condemned. Karl Barth's Commentary on Romans remains the classic statement of Neo-Orthodox Christian theology.

Jewish and Muslim Views of Paul

Because Paul is responsible more than anyone else for molding Christianity into a universal religion and cutting off many of its Jewish roots in the process, an assessment of Paul is often a part of Jewish reflection on Christianity, and Christian reflection on the Jewish-Christian relationship.

Paul the inventor of Christianity

Among Jews, the opinion is widely held that Paul "invented" Christianity by combining the sectarian Judaism of Jesus and his Jewish followers with Hellenistic religious ideas. They see Paul as an apostate from Judaism. While the teachings of Jesus the Jew may be the basis of Christian ethics, they view Paul's teachings as the basis of those Christian beliefs that separate it from Judaism, notably the atoning death of Jesus and the concept of original sin.

A leading proponent of this view is Talmudic scholar Hyam Maccoby in his books The Mythmaker and Paul and Hellenism. He notes that Paul was raised in an environment saturated with the popular Hellenistic mystery religions with their dying and resurrected savior deities. While for a time he had become a Pharisee who hoped to become a Jewish scholar, Paul's work persecuting the enemies of the High Priest led to an internal conflict in his mind, which manifested itself while he was traveling to Damascus on a covert mission. Maccoby believes that Paul's revelation was thus actually a resolution of his divided self. Paul subsequently fused the mystery religions, Judaism and the Passion of Jesus into an entirely new belief, centered on the death of Jesus as a mystical atoning sacrifice. Maccoby contends that Paul invented many of the key concepts of the Christian religion, and that the Gospels and other later Christian documents were written to reflect Paul's views rather than the authentic life and teaching of Jesus. Maccoby also denies that Paul was ever an educated Jew and that his claims to a Pharisaic education were false, pointing to passages in Paul's writings that betray his ignorance of Jewish Law.

Joseph Klausner (1874-1960) believed that Paul “negated Judaism.” Paul wanted Judaism to be of universal, not only of nationalistic significance, and knew that gentile hearts were crying out for a savior, so offered them one, spiritualizing the “once flesh and blood Jesus” (449). Yet in universalizing Judaism, said Klausner, Paul “alongside strange… [and] superstitious” notions about a dying and rising savior and a Messiah who had already come, enabled “gentiles [to] accept ... the Jewish Bible” as their faith's “foundation and basis” and can thus be described as a “preparer of the way for the King-Messiah” who is yet to come (1944, 610). The real Jesus had pointed people towards God, not to himself.

In the same line of thought, some Muslim scholars regard Paul as having distorted Jesus' true teaching. Ibn Taymiyya (d 1328) wrote that Paul constructed “a religion from two religions - from the religion of the monotheistic prophets and from that of idolaters” (Michel 1084, 346). Muslims, who firmly reject the deification of Jesus, sometimes put the blame on Paul for what they see as this Christian deviation, one that is condemned in the Qur'an. Thus, Bawany (1977) writes that “due to Paul, Jesus acquired a dual personality and became both God and Man” (187). Rahim (1977) says that Paul produced a mixture of Jewish Unitarianism and pagan philosophy. He “knew that he was lying” but believed that the end justified the means (71). In this process, “Jesus was deified and the words of Plato were put into his sacred mouth” (72). Real Christianity was represented by Barnabas (Paul's one time companion, see Acts 13:1) who later split from him (Acts 16:39). Many Muslims believe that a text called the Gospel of Barnabas is the authentic injil, or Gospel. Rahim says that Barnabas, not Paul, “endeavored to hold to the pure teaching of Jesus” (51).

Maqsood (2000) thinks it significant that Marcion considered Paul to be the only true apostle, stressing the complete break with Judaism (91). She also thinks it likely that the practice of the Lord's Supper, as a sacrificial meal, started with Paul, as did Trinitarian (251; 208). Since the Muslim Jesus did not die on the Cross, the centrality of the Cross in much Christian thought is regarded as an innovation and is also often attributed to Paul, who possibly confused the real Jesus about which he knew very little with a mythical or legendary Jesus (Maqsood, 105). Thus, If the Church had to depend on the letters of Paul, who apparently cared little for the earthly life of Jesus, “it would know almost nothing of… Jesus” (107).

While it is convenient for Muslims to blame all so-called Christian deviations on Paul, there is considerable evidence that the early Christians prior to Paul firmly believed that Jesus did die on the cross, and that the Lord's Supper was instituted by Jesus himself, while the doctrine of the Trinity and the Christology that equated Jesus with God probably developed subsequent to Paul.

Paul the Jewish inclusionist

The opposite opinion was first set forth by Rabbi Jacob Emden (1697–1776), based on the medieval Toledot Yeshu narratives, that Saul of Tarsus was a devout and learned Pharisee, who (turning away from his early Shammaite views) came to believe in salvation for the Gentiles. Under the guiding authority of the learned and devout Simon Kepha (i.e., Saint Peter), he set about refining a Noahide religion for the Gentiles based around the Jesus movement. Paul affirmed the advantage of the Jews in being entrusted with the oracles of heaven and in keeping the burden of the Law. But he opposed the Jewish Christians who insisted (under some kind of Shammaite influence) that Gentiles were beyond salvation unless they became Jews. Paul did however insist that any man born of a Jewish woman be circumcised (for example Timothy upon whom he himself carried out the ceremony) and live under the Law.

In recent years perhaps the most exemplary developers of Emden's view are the Orthodox Rabbi Harvey Falk and Pamela Eisenbaum.[7] In this view, Paul is seen as a rabbi who understood the ruling that, although it would be forbidden to a Jew, shittuf (believing in the divine through the name of another) would be permissible for a Gentile despite the Noahide ban on idolatry. Again when he spoke to the Greeks about a divinity in their pantheon called ‘The Unknown God’ (Acts 17:23), it can be understood that he was trying to de-paganize their native religions for the sake of their own salvation.

Other Jewish writers who have praised Paul as a Jew searching for a Jewish answer to the problem of including non-Jews in the realm of salvation include Richard Rubenstein, who in My Brother Paul (1972) wrote that while he could not share Paul's answer, which was to see Christ as the ultimate “solution to the problems of mankind” in relation to God, he could “strongly empathize with him” (22). He saw Paul as making explicit what was repressed in Judaism. Samuel Sandmel (1958) called Paul a “religious genius” for whom law and scripture were not fixed but “a continuous matter.” He did not see himself as “departing from scripture, but from the Law encased in it, for the revelation contained in scripture had not come to an end” (59-60).

Notes

- ↑ Some scholars, such as Helmut Koester, have expressed doubts that Paul studied in Jerusalem under this famous rabbi. Others, like Bruce Chilton (2004) see Gamaliel's influence in Paul's practice of writing letters: “it can't be sheer coincidence that the apostle who pioneered the art of writing personally to particular communities had studied in Jerusalem as a Pharisee during Gamaliel's time” (40).

- ↑ Wayne A. Meeks and L. Michael White, Paul's Missions and Letters "From Jesus to Christ: the First Christians," PBS Frontline. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ↑ Norman Perrin. The New Testament: An Introduction. (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1974), 92.

- ↑ This is the conservative consensus.

- ↑ Bruce Chilton. Rabbi Paul: An Intellectual Biography. (New York: Image Books, 2004), 265.

- ↑ Barbara Hall, Paul and Women Theology Today 31/1 (April 1974).

- ↑ Pamela Eisenbaum, "Is Paul the Father of Misogyny and Antisemitism?," Cross Currents 50, no. 4 (Winter 2000–2001).

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barth, Karl. A Shorter Commentary on Romans. John Knox Press, 1963.

- Baur, Ferdinand Christian. 1878. Church History of the First Three Centuries, Vol. 1. Edited by Allan Menzies. London: Williams and Norgate (first published in German, 1853).

- Bawany, E. A. Islam. The First and Final Religion. Karachi: Begum Aisha Bawany Waqf.

- Badenas, Robert. 1985. Christ the End of the Law, Romans 10.4 in Pauline Perspective 1985 ISBN 0905774930

- Brown, Raymond E. 1997. An Introduction to the New Testament. Anchor Bible Series. ISBN 0385247672.

- Bruce, F.F. 2000. Paul: Apostle of the Heart Set Free Grand Rapids, MI: Willima Eerdmans. ISBN 0802847781

- Chilton, Bruce. 2004. Rabbi Paul: An Intellectual Biography, New York: Image Books. ISBN 0385508638

- Dunn, James D. G. 1990. Jesus, Paul and the Law. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0664250955

- Hart, Michael. 1992. The 100: A Ranking of the 100 most influential people in history. Sacramento, CA: Citadel Press, Kensington Publishing Group. ISBN 0806513500.

- Klausner, Joseph. 1944. From Jesus to Paul. London: George, Allen & Unwin.

- Maccoby, Hyam. 1986.The Mythmaker: Paul and the Invention of Christianity. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060155825.

- MacDonald, Dennis Ronald. 1983. The Legend and the Apostle: The Battle for Paul in Story and Canon. Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press. ISBN 0664244645

- Maqsood, Wars. 2000. The Mysteries of Jesus. Oxford: Sakina Books. ISBN 0953805670

- Michel, Thomas (ed). 1984. A Muslim Theologians Response to Christianity: Ibn Taymiyya's Al-Jawab Al-Sahih. Dedlmar, NY: Caravan Books. ISBN 0882060589

- Rahim, Muhammad Ata-ur. 1977. Jesus, Prophet of Islam. Revised edition, 2000. Elmhurst, NY: Tahrike Tarsile Qur'an, Inc. ISBN 1879402114

- Rubenstein, Richard. 1972. My Brother Paul. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0061318442

- Sanders, E. P. 1977. Paul and Palestinian Judaism. Minneapolis, MN: Augsburg Fortress Press. ISBN 0800618998

- Sandmel, Samuel. 1958.The Genius of Paul: A Study in History. New York: Farrar, Strauss and Cudahy. Reprint edition, 1979. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press. ISBN 0800613708

- Wells, G. A. 1975. Did Jesus Exist? London: Elek Books.

- Wilson, N. 1992. A Jesus: A Life. London: Sinclair-Stevenson. ISBN 0449908070

- Wilson, N. A. Paul: The Mind of the Apostle. London: Sinclair-Stevenson and New York: W. W. Norton, 1997. ISBN 039331709

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Epistles of Apostle Paul Bishop Alexander (Orthodox Christian perspective)

- St. Paul, Catholic Encyclopedia, 1911 ed. newadvent.org.

- The Apostle and the Poet: Paul and Aratus Dr. Riemer Faber

- New Perspective on Paul The Paul Page.com. New theological approach of E.P. Sanders, James D.G. Dunn, N.T. Wright, and others

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Saul of Tarsus

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 05:28:11 | 389 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Paul_the_Apostle | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF