Pomona College

From Handwiki

From Handwiki  | |

| Type | Private liberal arts college |

|---|---|

| Established | October 14, 1887 |

Academic affiliation | Claremont Colleges |

| Endowment | $NaN (2021) |

| Budget | $NaN (2021) |

| Location | Claremont , California , United States Coordinates: 34°05′53″N 117°42′50″W / 34.09806°N 117.71389°W |

| |u}}rs | Blue and white[1][lower-alpha 1] |

| Nickname | Sagehens |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division III – SCIAC |

| Mascot | Cecil the Sagehen |

| Website | www |

| |

Pomona College (/pəˈmoʊnə/ (![]() listen) pə-MOH-nə[4]) is a private liberal arts college in Claremont, California. It was established in 1887 by a group of Congregationalists who wanted to recreate a "college of the New England type" in Southern California, and in 1925 it became the founding member of the Claremont Colleges consortium of adjacent, affiliated institutions.

listen) pə-MOH-nə[4]) is a private liberal arts college in Claremont, California. It was established in 1887 by a group of Congregationalists who wanted to recreate a "college of the New England type" in Southern California, and in 1925 it became the founding member of the Claremont Colleges consortium of adjacent, affiliated institutions.

Pomona is a four-year undergraduate institution and enrolled approximately 0 students as of the Template:Semester 2021 semester. It offers 48 majors in liberal arts disciplines and roughly 650 courses, though students have access to more than 2000 additional courses at the other Claremont Colleges. The college's [convert: needs a number] campus is in a residential community 35 miles (56 km) east of downtown Los Angeles near the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains.

Pomona has the lowest acceptance rate of any U.S. liberal arts college, and is generally considered the most prestigious liberal arts college in the American West and one of the most prestigious in the country.[5] It has a $NaN endowment (As of November 2021), giving it the seventh-highest endowment per student of any college or university in the U.S. The college's student body is noted for its racial,[6][7] geographic,[8] and socioeconomic[7][9] diversity. Its athletics teams are fielded jointly with Pitzer College and compete as the Sagehens in the SCIAC, a Division III conference.

Prominent alumni of Pomona include Oscar, Emmy, Grammy, and Tony award winners; U.S. Senators, ambassadors, and other federal officials; Pulitzer Prize recipients; billionaire executives; a Nobel Prize laureate; National Academies members; and Olympic athletes.[10] The college is a top producer of Fulbright scholars[11] and recipients of other fellowships.

History

.jpg/300px-Exterior_view_of_Pomona_College,_Claremont,_1907_(CHS-3857).jpg)

Founding era

Pomona College was established as a coeducational and nonsectarian Christian institution on October 14, 1887, amidst a real estate boom and anticipated population influx precipitated by the arrival of a transcontinental railroad to Southern California.[14][15] Its founders, a regional group of Congregationalists, sought to create a college in the mold of the New England institutions where many of them had been educated.[14][16][17] Classes first began at Ayer Cottage, a rental house in Pomona, California, on September 12, 1888, with a permanent campus planned at Piedmont Mesa four miles north of the city.[14][18] That year, as the real estate bubble burst, making the Piedmont campus untenable, the college was offered the site of an unfinished hotel (which it later renamed Sumner Hall[13]) in the nearby, recently founded town of Claremont; it moved there[18] but kept the Pomona name[19] (the city was itself named after the goddess of fruitful abundance in Roman mythology[20]).[21] Trustee Charles B. Sumner led the college during its first years, helping hire its first official president, Cyrus G. Baldwin, in 1890.[21][18][22] The first graduating class, in 1894, had 11 members.[23][24]

Pomona suffered through a severe financial crisis during its early years but managed to survive,[13][24][26] raising enough money to add several buildings to its campus.[27][28] Although the first Asian and black students enrolled in 1897[29] and 1900,[30] respectively, the college (like most others of the era) remained almost all-white throughout this period.[24][31] In 1905, during president George A. Gates' tenure, the college acquired a 64-acre (26 ha) parcel of land to its east known as the Wash.[32][33] In 1911, as high schools became more common in the region, the college eliminated its preparatory department, which had taught pre-college level courses.[34][35] The following year, it committed to a liberal arts model,[36] soon after turning its previously separate schools of art and music into departments within the college.[37][38] In 1914, the Phi Beta Kappa honor society established a chapter at the college.[39][40] Daily attendance at chapel was mandated until 1921,[41][42] and student culture emphasized athletics[43][44] and class rivalries.[45][46] During World War I, male students were divided into three military companies and a Red Cross unit to assist in the war effort.[47][48][49]

Interwar years

.jpg/300px-Soldiers_Drilling_at_Pomona_College_(1943).jpg)

In the early 1920s, Pomona's fourth president, James A. Blaisdell, was confronted with growing demand and considered whether to grow the college into a large university that could acquire additional resources or remain a small institution capable of providing a more intimate educational experience. Ultimately, seeking both, he chose an alternative path inspired by the collegiate university model he observed at Oxford, envisioning a group of independent colleges sharing centralized resources such as a library.[51][52] On October 14, 1925, Pomona's 38th anniversary, the Claremont Colleges were incorporated.[53][54] Construction of the Clark dormitories north of 6th Street began in 1929, a reflection of president Charles Edmunds' prioritization of the college's residential life.[55][56][57] Edmunds, who had previously served as president of Lingnan University in Guangzhou, China, also inspired a growing interest in Asian culture at the college and established its Asian studies program.[58][56]

Pomona's enrollment and budget declined during the Great Depression.[59][60][61] The college reoriented itself toward wartime activities again during World War II ,[62][63][64] hosting an Air Force military meteorology program[65] and Army Specialized Training Program courses in engineering and foreign languages.[50][66]

Postwar transformations

Pomona's longest-serving president, E. Wilson Lyon, guided the college through a transformational period from 1941 to 1969.[67][62] Following the war, Pomona's enrollment rose above 1000,[68][45] leading to the construction of several residence halls and science facilities.[69][70] Its endowment also grew steadily, due in part to the introduction in 1942 of a deferred giving fundraising scheme pioneered by Allen Hawley called the Pomona Plan, where participants receive a lifetime annuity in exchange for donating to the college upon their death.[71][64][72] The plan's model has since been adopted by many other colleges.[73][74][75]

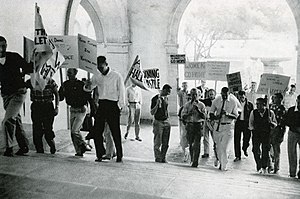

Lyon made a number of progressive decisions relating to civil rights, including supporting Japanese-American students during internment[63][77][78] and establishing an exchange program with Fisk University, a historically black university in Tennessee, in 1952.[79][80][81] He also ended the gender segregation of Pomona's residential life, first with the opening of Frary Dining Hall (then part of the men's campus) to women beginning in 1957[76] and later with the introduction of co-educational housing in 1968.[82] However, he wavered when it came to some of the more radical student protests against the Vietnam War, and permitted Air Force recruiters to come to campus in 1967.[83][84][85][86] Pomona's previously conservative student body quickly liberalized during this era,[62][85] and its ethnic diversity also began to increase.[87][44][88] In 1969, a bomb exploded at the Carnegie Building, permanently injuring a secretary; no culprit was ever identified.[89][88][90]

During the tenure of president David Alexander from 1969 to 1991, Pomona gained increased prominence on the national stage.[91] The endowment also increased ten-fold, enabling the construction and renovation of a number of buildings.[88] Several identity-based groups, such as the Pomona College Women's Union (founded 1984[92]), established themselves.[93] In the mid-1980s, out-of-state students began to outnumber in-state students.[94]

In 1991, the college converted the dormitory basements used by fraternities into lounges, arguing that this created a more equitable distribution of campus space. The move hastened a lowering of the profile of Greek life on campus.[95][96]

21st century

In the 2000s, under president David W. Oxtoby, Pomona began placing more emphasis on reducing its environmental impact,[99][100] committing in 2003 to obtaining LEED certifications for new buildings[101][102] and launching various sustainability initiatives.[99][101] The college also entered partnerships with several college access groups (including the Posse Foundation in 2004 and QuestBridge in 2005) and committed to meeting the full demonstrated financial need of students through grants rather than loans in 2008.[103] These efforts, combined with Pomona's previously instituted[104] need-blind admission policy, resulted in increased enrollment of low-income and racial minority students.[105]

In 2008, Pomona stopped singing its alma mater at convocation and commencement after it was discovered that the song may have been originally written to be sung as the ensemble finale to a student-produced blackface minstrel show performed on campus in 1909 or 1910. Some alumni protested the move.[100][106][107]

In 2011, Pomona requested proof of legal residency from employees in the midst of a unionization drive by dining hall workers.[108][109] 17 workers who were unable to provide documentation were fired, drawing national media attention and sparking criticism from activists;[108][110] the dining hall staff voted to unionize in 2013.[111][112] A rebranding initiative that year sought to emphasize students' passion and drive, angering students who thought it would lead to a more stressful culture.[113] Several protests in the 2010s criticized the college's handling of sexual assault,[114][115] leading to reforms.[116][117]

In 2017,[118] G. Gabrielle Starr became Pomona's tenth president; she is the first woman and first African American to hold the office.[119][120] From March 2020 through the spring 2021 semester, the college switched to online instruction in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[121][122]

Campus

Pomona's [convert: needs a number] campus is in Claremont, California, an affluent suburban residential community[124] 35 miles (56 km) east of downtown Los Angeles .[54] It is directly northwest of the Claremont Village (the city's downtown commercial district) and directly south of the other contiguous Claremont Colleges.[125] The area has a Mediterranean climate[126] and consists of a gentle slope from the alluvial fan of San Antonio Creek in the San Gabriel Mountains to the north.[127]

In its early years, Pomona quickly expanded from its initial home in Sumner Hall, constructing several buildings to accommodate its growing enrollment and ambitions.[128][28] After 1908, development of the campus was guided by master plans from architect Myron Hunt, who envisioned a central quadrangle flanked by buildings connected via visual axes.[123] In 1923, landscape architect Ralph Cornell expanded on Hunt's plans, envisioning a "college in a garden" defined by native Southern California vegetation.[123] President James Blaisdell's decision to purchase undeveloped land around Pomona while it was still available later gave the college room to grow and found the consortium.[129] Many of the earlier buildings were constructed in the Mission Revival and Spanish Colonial Revival styles, with stucco walls and red terracotta tile roofs.[48] Other and later construction incorporated elements of neoclassical, Victorian, Italian Romanesque, modern, and postmodern styles.[123] As a result, the present campus features a varied blend of architectural styles.[130] Most buildings are three or fewer stories in height,[131] and are designed to facilitate both indoor and outdoor use.[130]

.jpg/380px-Athern_Field,_Pomona_College_(cropped).jpg)

Template:Panorama link

The campus consists of 88 facilities (As of 2020),[133] including 70 addressed buildings.[134] It is bounded by First Street on the south, Mills and Amherst Avenues on the east, Eighth Street on the north, and Harvard Avenue on the west.[131] It is informally divided into North Campus and South Campus by Sixth Street,[135] with most academic buildings in the western half and a naturalistic area known as the Wash in the east.[131]

Pomona has undertaken initiatives to make its campus more sustainable, including requiring that all new construction be built to LEED Gold standards,[136] replacing turf with drought-tolerant landscaping,[137] and committing to achieving carbon neutrality without the aid of purchased carbon credits by 2030.[138] The Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education gave the college a gold rating in its 2018 Sustainable Campus Index.[139]

South Campus

South Campus consists of mostly first-year and second-year housing and academic buildings for the social sciences, arts, and humanities.[131]

South of Bonita Avenue is a row of residence halls, comprising Wig Hall (built 1959), Harwood Court (built 1921), Lyon Court (built 1990), Mudd-Blaisdell Halls (built 1947 and 1936, respectively), and Gibson Hall (built 1949).[131] Sumner Hall, the home of admissions and several other administrative departments, is located to the north of the dormitories, and Frank Dining Hall is located to the east.[131] Oldenborg Center, a foreign language housing option that includes a foreign language dining hall, is across from Sumner.[140][141]

Template:Panorama link

South Campus has several arts buildings and performance venues. Bridges Auditorium ("Big Bridges", built 1931) is used for concerts and speakers and has a capacity of 2,500.[142][143] Bridges Hall of Music ("Little Bridges", built 1915) is a concert hall with seating for 550.[144] It is adjacent to Thatcher Music Building (built 1970).[123] On the western edge of campus is the Benton Museum of Art (built 2020), which has a collection of approximately 15,000 works,[145] including Italian Renaissance panel paintings, indigenous American art and artifacts, and American and European prints, drawings, and photographs.[146][147] The Seaver Theatre Complex (built 1990) has a 335-seat thrust stage theater and 125-seat black box theater, among other facilities.[148] The Studio Art Hall (built 2014) garnered national recognition for its steel-frame design.[97][98] Pendleton Dance Center (built 1970 as a women's gym) is south of the residence halls.[123]

Pomona's main social science and humanities buildings are located west of College Avenue. They include the Carnegie Building (built 1908 as a library),[131] Hahn Hall (built 1990),[123] and the three buildings of the Stanley Academic Quadrangle: Pearsons Hall (built 1898), Crookshank Hall (built 1922), and Mason Hall (built 1923).[131]

Marston Quadrangle, a 5-acre (2 ha) lawn framed by California sycamore and coastal redwood trees, serves as a central artery for the campus, anchored by Carnegie on the west and Bridges Auditorium on the east.[123] To its north is Alexander Hall (built 1991), which houses administrative offices,[131] and the Smith Campus Center (built 1999), home to many student services, as well as a recreation room, the Coop Store, and two restaurants.[149] East of the Smith Campus Center is the Rains Center (built 1989 and renovated 2021[150]), Pomona's primary indoor athletics and recreation facility, and Smiley Hall dormitory (built 1908).[131]

<section begin="gates"/>

At the intersection of Sixth Street and College Avenue are the college gates, built in 1914, which mark the historical northern terminus of the campus. They bear two quotes from President Blaisdell. On the north is "let only the eager, thoughtful and reverent enter here", and on the south is "They only are loyal to this college who departing bear their added riches in trust for mankind". Per campus tradition, enrolling students walk south through the gates during orientation and seniors walk north through the gates shortly before graduation.[151][152]<section end="gates"/>

The less-developed 40-acre (16 ha)[123] eastern portion of campus is known as the Wash (formally Blanchard Park[153]),[33] and contains a large grove of coast live oak trees,[154] as well as many athletics facilities. It is also home to the Sontag Greek Theatre (built 1914), an outdoor amphitheater; the Brackett Observatory (built 1908); and the Pomona College Organic Farm, an experiment in sustainable agriculture.[131]

Harwood Court

The Wash

Bridges Hall of Music

Bridges Auditorium

The Carnegie Building

Mason Hall

Pearsons Hall

North Campus

North Campus was designed by architect Sumner Spaulding,[155] and consists primarily of residential buildings for third- and fourth-year students and academic buildings for the natural sciences.[131]

The academic buildings are located to the west of North College Way. They include Lincoln and Edmunds Halls (built 2007), Andrew Science Hall and Estella Laboratory (built 2015), the Seeley G. Mudd Building (built 1983[156]), Seaver North (built 1964[157]), Seaver South (built 1958[70]), and the Seaver Biology Building (built 2005[158]).[131] The courtyard between Lincoln and Edmunds contains Dividing the Light, a skyspace by well-known artist and alumnus James Turrell.[159][160]

The residence halls include the Clark Halls (I, III, and V;[lower-alpha 2] built 1930), Walker Hall (built 1953), Norton Hall (built 1956), Lawry Court (built 1980), and Dialynas and Sontag Halls (built 2011).[131] The North Campus dining hall, Frary Dining Hall (built 1930), features a vaulted ceiling and is the location of the murals Prometheus by José Clemente Orozco[161] and Genesis by Rico Lebrun.[162][131]

Walker Hall

Norton-Clark III courtyard

Dividing the Light skyspace

_de_José_Clemente_Orozco_en_Pomona_College.jpg/271px-Prometheus_(1930)_de_José_Clemente_Orozco_en_Pomona_College.jpg)

Prometheus mural

Walker Beach, looking north

Walker Beach, looking south

Other facilities

The college also owns the 53-acre (21 ha) Trails Ends Ranch (a wilderness area in the Webb Canyon north of campus),[163][164] the 320-acre (130 ha) Mildred Pitt Ranch in southeastern Monterey County,[165] and the Halona Lodge retreat center (built 1931) in Idyllwild, California.[166][167] The astronomy department built and operates a telescope at the Table Mountain Observatory.[168]

Along the north side of campus are several joint buildings maintained by The Claremont Colleges Services. These include the Tranquada Student Center, home to student health and psychological services, Campus Safety, and the Huntley Bookstore.[131] {{#section:Claremont Colleges|library holdings}} The consortium also owns the Robert J. Bernard Field Station north of Foothill Boulevard.[169]

Organization and administration

Governance

Pomona is governed as a nonprofit organization by a board of trustees responsible for overseeing the long-term interests of the college.[170] The board consists of up to 42 members, most of whom are elected to four-year terms with a term limit of 12 years.[lower-alpha 3][170] It is responsible for hiring the college's president (currently ), approving budgets, setting overarching policies, and various other tasks.[170] The president, in turn, oversees the college's general operation, assisted by a faculty cabinet.[170] Other officer and leadership roles defined in the college's bylaws are vice president for academic affairs and dean of the college, vice president for student affairs and dean of students, vice president for advancement, vice president and treasurer, vice president and dean of admissions and financial aid, registrar, and secretary to the board.[170] The college has total employees as of the Template:Semester 2021 semester. Pomona operates under a shared governance model, in which faculty and students sit on many policymaking committees and have a degree of control over other major decisions.[171][172][173]

Academic affiliations

Pomona is the founding member of the Claremont Colleges (colloquially "7Cs", for "seven colleges"), a consortium of five undergraduate liberal arts colleges ("5Cs")—Pomona, Scripps, Claremont McKenna, Harvey Mudd, and Pitzer—and two graduate schools—Claremont Graduate University and Keck Graduate Institute. All are located in Claremont. Although each member has individual autonomy and a distinct identity,[174] there is substantial collaboration through The Claremont Colleges Services (TCCS), a coordinating entity that manages the central library, campus safety services, health services, and various other resources.[175] Overall, the 7Cs have been praised by higher education experts for their close cooperation,[176] although there have been occasional tensions.[177][178] Pomona is the largest[178] and wealthiest member.[179]

Pomona is also a member of several other consortia of selective colleges, including the 568 Group,[180] the Consortium of Liberal Arts Colleges,[181] the Oberlin Group,[182] and the Annapolis Group.[183] The college is accredited by the WASC Senior College and University Commission, which reaffirmed its status in 2021 with particular praise for its diversity initiatives.[184][185]

Finances

Pomona has an endowment of $NaN (As of November 2021), giving it the seventh-highest endowment per student of any college or university in the U.S.[186] The college's total assets (which includes the value of its campus) are $NaN. Its operating budget for the 2021–2022 academic year is $NaN, of which roughly half is funded by endowment earnings.[187] 38 percent of the budget was allocated to instruction, 2 percent to research, 1 percent to public service, 11 percent to academic support, 13 percent to student services, 18 percent to institutional support, and 17 percent to auxiliary expenses. In October 2020, Fitch Ratings gave the college a AAA bond credit rating, its highest rating, reflecting an "extremely strong financial profile".[188]

Academics and programs

Pomona offers instruction in the liberal arts disciplines and awards the bachelor of arts degree.[189] The college operates on a semester system,[190] with a normal course load of four full-credit classes per semester.[191] 32 credits and a C average GPA are needed to graduate, along with the requirements of a major, the first-year critical inquiry seminar, at least one course in each of six "breadth of study" areas,[lower-alpha 4] proficiency in a foreign language, two physical education courses, a writing intensive course, a speaking intensive course, and an "analyzing difference" course (typically examining a type of structural inequality).[192]

Pomona offers 48 majors,[189] most of which also have a corresponding minor.[lower-alpha 5][193] For the 2020 graduation cohort, 22 percent of students majored in the arts and humanities, 37 percent in the natural sciences, 21 percent in the social sciences, and 19 percent in interdisciplinary fields.[194] 15 percent of students completed a double major, 29 percent completed a minor, and 3 percent completed multiple minors.[195] The college does not permit majoring in pre-professional disciplines such as medicine or law but offers academic advising for those areas[196][197] and 3-2 engineering programs with CalTech, Dartmouth, and Washington University.[198]

Courses

Individually, Pomona offers approximately 650 courses per semester.[199] However, students may take a significant portion[lower-alpha 6] of their courses at the other Claremont Colleges, enabling access to approximately 2700 courses total.[191] The academic calendars and registration procedures across the colleges are synchronized and consolidated,[200] and there are no additional fees for cross-enrollment.[94] In addition, students may create independent study courses evaluated by faculty mentors.[201]

All classes at Pomona are taught by professors.[202] The average class size is 15;[199] for the fall 2020 semester, 96 percent of traditional courses[lower-alpha 7] had under 30 students, and only one had 50 or more students.[203] The college employs faculty members as of the Template:Semester 2021 semester, approximately three quarters of whom are full-time,[203] resulting in a 7:1 ratio of students to full-time equivalent professors.[203] Among full-time faculty, 35 percent are members of racial minority groups, 46 percent are women, and 98 percent have a doctorate or other terminal degree in their field.[203] Students and professors often form close relationships,[204] and the college provides faculty with free meals that can be used to interact with students.[173] Semesters end with a week-long final examination period preceded by two reading days.[205] The college operates several resource centers to help students develop academic skills, including the Quantitative Skills Center (QSC);[206][207] the Center for Speaking, Writing, and the Image;[208] and the Foreign Language Resource Center (FLRC).[209]

Research, study abroad, and professional development

More than half of Pomona students conduct research with faculty.[210][211] The college sponsors a Summer Undergraduate Research Program (SURP) every year, in which more than 200 students are paid a stipend of up to $5,600 to conduct research with professors or pursue independent research projects with professorial mentorship.[212][213] The Pomona College Humanities Studio, established in 2018, supports research in the humanities.[214] Pomona is home to the Pacific Basin Institute, a research institute that studies issues pertaining to the Pacific Rim.[215] {{#section:Claremont Colleges|Hive}}

Approximately half of Pomona students study abroad.[210] (As of 2021), the college offers 63 pre-approved programs in 36 countries.[216] Pomona also offers study-away programs for Washington, D.C., Silicon Valley, and the Marine Biological Laboratory in Massachusetts, and semester exchanges at Colby, Spelman, and Swarthmore colleges.[198]

The Pomona College Career Development Office (CDO) provides students and alumni with career advising, networking, and other pre-professional opportunities. It runs the Pomona College Internship Program (PCIP), which provides stipends for completing unpaid or underpaid internships during the semester or summer; more than 250 students participate annually.[217][218] The office also connects students with alumni for networking and mentoring via the Sagehen Connect platform.[219] During the 2015–2016 academic year, 175 employers hosted on-site informational events at the Claremont Colleges and 265 unique organizations were represented in 9 career fairs.[219]

Outcomes

For the 2019 entering class, 97 percent of students returned for their second year, giving Pomona one of the highest retention rates of any college or university in the U.S.[220] For the 2014 entering class, 89 percent of students graduated within four years (the highest rate of any U.S. liberal arts college[221]) and 94 percent graduated within six years.[203]

Within 10 years, 81 percent of Pomona graduates attend graduate or professional school.[210] The college ranked 10th among all U.S. colleges and universities for doctorates awarded to alumni per capita, according to data collected by the National Science Foundation.[222] The top destinations between 2009 and 2018 (in order) were the University of California, Los Angeles; the University of California, Berkeley; Harvard University; the University of Southern California; and Stanford University.[219] A 2020 analysis of top feeder schools per capita to the highest-ranked U.S. medical, business, and law schools placed Pomona 10th for medical schools, 16th for business schools, and 10th for law schools.[223]

The top industries for graduates are technology; education; consulting and professional services; finance; government, law, and politics; arts, entertainment, and media; healthcare and social services; nonprofits; and research.[224][225][226] Pomona alumni earn a median early career salary of $69,100 and a median mid-career salary of $137,800, according to 2020 survey data from PayScale.[227]

Many Pomona students pursue competitive postgraduate fellowships. The college ranks among the top producers of Churchill Scholars,[228] Fulbright Scholars,[11][229][230] Goldwater Scholars,[231] Marshall Scholars,[232] National Science Foundation graduate research fellows,[233] and Rhodes Scholars.[234]

Reputation and rankings

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[235] | 12 |

| THE/WSJ[236] | 23 |

| Liberal arts colleges | |

| U.S. News & World Report[237] | 4 |

| Washington Monthly[238] | 6 |

Pomona is generally considered the most prestigious liberal arts college in the Western United States and one of the most prestigious in the country.<section begin=reputation reference/>[5]<section end=reputation reference/> However, among the broader public, it has less name recognition than many larger schools.[239][240]

The 2021 U.S. News & World Report Best Colleges Ranking places Pomona fourth in the national liberal arts colleges category out of 223 colleges.[237] Pomona has been ranked in the top 10 liberal arts colleges every year by U.S. News since it began ranking them in 1984, and is one of five schools with such a history, alongside Amherst, Swarthmore, Wellesley, and Williams.[241]

Pomona has generally rated similarly in other college rankings. In 2015, the Forbes ranking placed it first among all colleges and universities in the U.S., drawing media attention.[240] Pomona is the third most desirable college or university in the U.S., according to a 2020 analysis of admitted students' revealed preferences among their college choices conducted by the digital credential service Parchment.[242]

Admissions and financial aid

Admissions

Template:Infobox U.S. college admissions

Pomona offers three routes for students to apply: the Common Application, the QuestBridge application, and the Coalition Application. Applicants who want an earlier, binding decision to the college can apply either early decision I or II; others apply through regular decision.[243] Additionally, the college enrolls two 10-student[244] Posse Foundation cohorts, from Chicago and Miami, in each class.[245]

Pomona considers various factors in its admissions process, placing greatest importance on course rigor, class rank, GPA, test scores, application essay, recommendations, extracurricular activities, talent, and character. Interviews, first generation status, geographic residence, race and ethnicity, volunteer work, and work experience are considered. Alumni relationships, religious affiliation, and level of interest are not considered.[203] The college is part of many coalitions and initiatives targeted at recruiting underrepresented demographics.[246][247]

Pomona has the lowest acceptance rate of any national liberal arts college in the U.S.[248] For the 2021 entering class, Pomona admitted 0.0 percent of applicants. 47.8 percent of admitted applicants chose to enroll.[203] The number of transfer applicants admitted has varied by year; in 2020, Pomona admitted 39 of 396 applicants (9.8 percent).[203]

Costs and financial aid

.jpg/300px-Sumner_Hall,_Pomona_College_(cropped2).jpg)

For the 2021–2022 academic year, Pomona charged a tuition fee of $, with a total estimated on-campus cost of attendance of $. In 2020–2021, 55 percent of students received a financial aid package, with an average award of $56,395.[203] 49 percent of international students received financial aid, with an average award of $66,125.[203]

Pomona practices need-blind admission for students who are U.S. citizens, permanent residents, DACA status, undocumented, or graduates of a high school within the U.S., and need-aware admission for international students. It meets 100 percent of demonstrated need for all admitted students, including international students,[249][250] through grants rather than loans.[251] The college does not offer merit awards or athletics scholarships.[203]

People

Student body

(As of 2021), Pomona's student body consists of degree-seeking undergraduate students and a token number of non-degree seeking students. Compared to its closest liberal arts peers, Pomona is generally characterized as laid-back, academically-oriented, mildly quirky, and politically liberal.[8]

The student body is roughly evenly split between men and women, and 91 percent of students are less than 22 years old.[253] 56 percent of students are domestic students of color, and an additional 11 percent are international students,[252] making Pomona one of the most racially and ethnically diverse colleges in the U.S.[6][7][254][255] The geographic origins of the student body are also diverse,[8][253] with all 50 U.S. states, the major U.S. territories, and more than 60 foreign countries represented.[256][257] 27 percent of students are from California, and there are sizable concentrations from the other western states.[257] The median family income of students was $166,500 (As of 2013), with 52 percent of students coming from the top 10 percent highest-earning families and 22 percent from the bottom 60 percent.[258] The college has enrolled higher numbers of low-income students in recent years,[105] and was ranked second among all private institutions and eighth among all institutions in The New York Times ' 2017 College Access Index, a measure of economic diversity.[9]

For the 2020 entering class, the middle 50 percent of enrolled first-years scored 690–750 on the SAT evidence-based reading and writing section, 700–790 on the SAT math section, and 32–35 on the ACT.[203] 25 percent were valedictorians of their high school class,[257] 90 percent ranked in the top tenth, and 98 percent ranked in the top quarter (among students with an official class rank).[203]

Noted alumni and faculty

.jpg/180px-Professor_Jennifer_Doudna_ForMemRS_(cropped).jpg)

Pomona has approximately 25,000 living alumni.[260] Notable alumni include anthropologist David P. Barrows (1894);[24][261] pioneer of Chinese social science Chen Hansheng (1920);[262] U.S. Circuit judges James Marshall Carter (1924),[263] Stephen Reinhardt (1951),[264] and Richard Taranto (1977);[265][266] actors Joel McCrea (1928)[56][267] and Richard Chamberlain (1956);[268] avant-garde composer John Cage (attended 1928–1930);[269][270] U.S. Senators Alan Cranston (Template:USpolabbr; transferred c. 1934)[271][272] and Brian Schatz (Template:USpolabbr; 1994);[273][274] Flying Tigers member and Medal of Honor recipient James H. Howard (1937);[275][276] fourteen-time Grammy-winning conductor Robert Shaw (1938);[277] Gumby creator Art Clokey (1943);[50][278] senior Disney executive Roy E. Disney (1951);[279] several Oscar-winning screenwriters, including Robert Towne (1956)[268] and Jim Taylor (1984);[92] writer, actor, and musician Kris Kristofferson (1958);[70] Light and Space artist James Turrell (1965);[280][281] Civil Rights activist and NAACP chairperson Myrlie Evers-Williams (1968);[282][82] The New York Times executive editor Bill Keller (1970);[283][284] self-help author Marianne Williamson (attended 1970–1972);[285] Pulitzer-winning newspaper columnist Mary Schmich (1975);[286] and Nobel Prize-winning biochemist Jennifer Doudna (1985).[259][287]

Notable Pomona faculty include kabuki expert Leonard Pronko (taught 1957–2014),[288][289] former U.S. ambassadors Michael Armacost (1960s)[290] and Cameron Munter (2013–2015),[291][292] jazz musician Bobby Bradford (1974–present),[293] NBA basketball coach Gregg Popovich (1979–1988),[294] novelists David Foster Wallace (2002–2008)[100] and Jonathan Lethem (2011–present),[295][296] and poet Claudia Rankine (2006–2015).[297]

Student life

Residential life

Template:Panorama link

Pomona is a residential campus, and virtually all students live on campus for all four years in one of the college's 16 residence halls.[298] All first-year students live on South Campus, and most third- and fourth-year students live on North Campus.[298] All incoming students are placed into a sponsor group, with 10–20 peers and two or three upperclass "sponsors"[299][300] tasked with easing the transition to college life but not enforcing rules (a duty given to resident advisors).[301][302][303] Sponsor groups often share activities such as "fountaining", a tradition in which students are thrown into a campus fountain on their birthday.[304] The program dates back to 1927 for women and was expanded in 1950 to include men.[305][306]

Pomona's social scene is intertwined with that of the other 5Cs, with many activities and events shared between the colleges.[174] The college's alcohol policies are aimed at encouraging responsible consumption, and include a strict ban of hard liquor on South Campus.[307][308] Dedicated substance-free housing is also offered.[298] Overall, drinking culture is present but does not dominate over other elements of campus life,[309][310] nor does athletics culture.[311] Violations of the student code are typically handled by the student-run Judicial Council, known as "J-Board".[312][313]

Template:Panorama link

Pomona's dining services are run in-house.[315] All on-campus students are required to have a meal plan,[316] usable at any of the Claremont Colleges' seven buffet-style dining halls.[lower-alpha 8] The menus emphasize sustainable and healthy options, and the food quality is generally praised.[309][318] Every night Sunday through Wednesday, Frary Dining Hall opens for a late-night snack.[319][320][321] Meal plans also include "Flex Dollars" usable at the various campus eateries, including the Coop Fountain, Coop Store, and sit-down Sagehen Café in the Smith Campus Center.[322]

Campus organizations

Template:Panorama link

Some extracurricular organizations at Pomona are specific to the college, whereas others are open to students at all of the Claremont Colleges.[174] In total, there are nearly 300 clubs and organizations across the 5Cs.[324]

The Associated Students of Pomona College (ASPC) serves as Pomona's official student government.[325][326] Composed of elected representatives and appointed committee members, ASPC distributes funding for clubs and organizations, represents Pomona's student body in discussions with the administration, runs student programming (such as the Yule Ball dance[327] and Ski-Beach Day[328]) through the Pomona Events Committee (PEC), and provides various student services such as an airport rideshare program.[329][330]

{{#section:Claremont Colleges|Media}} Pomona's yearbook, Metate, was founded in 1894 and discontinued in 2012.[331]

Pomona has numerous clubs or support offices which provide resources and mentoring programs for students with particular identities. These include the Women's Union (WU), Office of Black Student Affairs (OBSA), Asian American Resource Center (AARC), Chicano Latino Student Affairs (CLSA), Improving Dreams Equality Access and Success (IDEAS, which supports undocumented and DACA students), International Student Mentor Program (ISMP), Multi-Ethnic and Multi-Racial Group Exchange (MERGE), Indigenous Peer Mentoring Program (IPMP), South Asian Mentorship Program (SAMP), Students of Color Alliance (SOCA), Queer Resource Center (QRC), and chaplains office.[324][332][333] The college's first-generation and low-income community, FLI Scholars, has more than 200 members.[334] The Campus Advocates and EmPOWER Center support survivors of sexual violence and work to promote consent culture.[335][336]

The Pomona Student Union (PSU) facilitates the discussion of political and social issues on campus by hosting discussions, panels, and debates with prominent speakers holding diverse viewpoints.[337] Other speech and debate organizations include a mock trial team, model UN team, and debate union.[338][324] Pomona's secret society, Mufti, is known for gluing small sheets of paper around campus with cryptic puns offering social commentary on campus happenings.[339][340]

Pomona's music department manages several ensembles, including an orchestra, band, choir, glee club, jazz ensemble, and Balinese gamelan ensemble.[341] All students can receive private music lessons at no cost.[342] {{#section:Claremont Colleges|A capella}}

The Draper Center for Community Partnerships, established in 2009, coordinates Pomona's various community engagement programs.[343] These include mentoring for local youth communities, English tutoring for Pomona staff, and the Alternabreak volunteering trips over spring break.[344] It also operates the Pomona Academy for Youth Success (PAYS), a three-year pre-college summer program for local low-income and first-generation students of color.[345]

Pomona has two remaining local Greek organizations, Sigma Tau and Kappa Delta, both of which are co-educational.[346] Neither have special housing, and they are not considered to have a major impact on the social scene on campus akin to that of Greek organizations at many other U.S. colleges.[347][346][96]

Traditions

47 reverence

Other traditions

As part of Pomona's 10-day orientation, incoming students spend four days off campus completing an "Orientation Adventure" or "OA" trip. Begun in 1995, the OA program is one of the oldest outdoor orientation programs in the nation.[348]

Every spring, the college hosts "Ski-Beach Day", in which students visit a ski resort in the morning and then head to the beach after lunch.[349] The tradition dates back to an annual mountain picnic established in 1891.[349]

Since the 1970s, Pomona has used a cinder block flood barrier along the northern edge of its campus, Walker Wall, as a free speech wall.[350] Over the years, provocative postings on the wall have spawned a number of controversies.[351][352][353][354]

Transportation

Pomona's campus is located immediately north of Claremont Station,[125] where the Metrolink San Bernardino Line train provides regular service to Los Angeles Union Station (the city's main transit hub)[355] and the Foothill Transit bus system connects to cities in the San Gabriel Valley and Pomona Valley.[356]

Pomona's Green Bikes program maintains a fleet of more than 300 bicycles that are rented to students each semester free of charge.[357] The college also has several Zipcar vehicles on campus that may be rented, and owns vehicles which can be checked out for club and extracurricular purposes. PEC and Smith Campus Center off-campus events are usually served with the college's 34-passenger bus, the Sagecoach.[358]

Athletics

Pomona's varsity athletics teams compete in conjunction with Pitzer College as the Pomona-Pitzer Sagehens.[359] The 11 women's and 10 men's teams participate in NCAA Division III in the Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (SCIAC).[359] Pomona-Pitzer's mascot is Cecil the Sagehen, a greater sage-grouse, and its colors are blue and orange.[360] Its main rival is the Claremont-Mudd-Scripps Stags and Athenas (CMS), the other sports combination of the Claremont Colleges.[361] {{#section:Pomona-Pitzer Sagehens|recent ranking}}

Club and intramural sports are also offered in various areas, such as dodgeball, flag football, and surfing.[362][363] The physical education department offers a variety of activity classes each semester, such as karate, playground games, geocaching, and social dance.[364]

Athletics facilities at Pomona include five basketball courts, four racquetball courts, two squash courts, a weight room, an exercise room, two pools, two tennis court complexes, a football field, a track, a softball field, a baseball field, and four fields for soccer, lacrosse, ultimate frisbee, and field hockey.[365]

Athletics history

.jpg/300px-Pomona_College_football_team,_1911_(cropped).jpg)

Pomona's first intercollegiate sports teams were formed in 1895.[366] They competed under a variety of names in the school's early years; the name "Sagehen" first appeared in 1913 and became the sole moniker in 1917.[367] Pomona was one of the three founding members of the SCIAC in 1914, and its football team played in the inaugural game at the Los Angeles Coliseum in 1923.[366] In 1946, Pomona joined with Claremont Men's College (which would later be renamed Claremont McKenna College) to compete as Pomona-Claremont.[366] The teams separated in 1956, and Pomona's athletics program operated independently until it joined with Pitzer College in 1970.[366]

Notes

- ↑ The college also frequently uses gold as an accent color,[2] and its athletics teams use blue and orange to represent both Pomona and Pitzer, its athletics partner.[3]

- ↑ The Clark numberings are derived from Spaulding's original plan for North Campus. Clark II became Frary Dining Hall, Clark VI became Walker Hall, and Clark VII became Walker Lounge. Clark IV and Clark VIII were never built.[155]

- ↑ The unelected trustees consist of the college's president and two non-voting ex-officio members, the chair of the alumni association and chair of national giving. At least 10 trustees must be alumni, including one who has graduated within the last 11 years.

- ↑ The six breadth of study areas are:

- Criticism, Analysis, and Contextual Study of Works of the Human Imagination

- Social Institutions and Human Behavior

- History, Values, Ethics and Cultural Studies

- Physical and Biological Sciences

- Mathematical and Formal Reasoning

- Creation and Performance of Works of Art and Literature

- ↑ Students may also petition to create their own custom major.

- ↑ Without special advisor approval, first-year students may cross-enroll for one course per semester, and others may cross-enroll for up to 40 percent of their total credits.

- ↑ The definition of "traditional course" excludes thesis classes, lab sections, and independent study courses.

- ↑ Meal swipes can also be used for ordered pack-out boxes,[316] or at Claremont McKenna's Marian Miner Cook Athenaeum.[317] The dining halls offer green clamshell takeout boxes for meals to go.[121]

References

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 42.

- ↑ "Graphic Standards Manual". Pomona College. http://www.pomona.edu/sites/default/files/graphic-standards-guide.pdf.

- ↑ "Cecil Image and Athletics Color Usage Guidelines" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/communications/logos-guidelines/cecil-image-and-athletics-color-usage-guidelines.

- ↑ "Pomona" (in en). Collins English Dictionary. https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/pomona.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Characterizations of the reputation of Pomona College:

- Barber, Mary (November 15, 1987). "Claremont Colleges: What began 100 years ago in an empty hotel surrounded by sagebrush has evolved into a unique success in American higher education" (in en). Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-11-15-ga-20720-story.html. "Several studies rate Pomona as one of the country’s best private liberal arts colleges"

- Fiske 2021, p. 154: "the undisputed star of the Claremont Colleges and one of the top small liberal arts colleges anywhere. This small, elite institution is the top liberal arts college in the West."

- Goldstein, Dana (17 September 2017). "When Affirmative Action Isn't Enough". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/17/us/affirmative-action-college.html. "an elite liberal arts school"

- Greene & Greene 2016, p. 550: "the leading liberal arts college west of the Rocky Mountains"

- Ringenberg, William C. (December 1978). "Review of The History of Pomona College, 1887–1969". The American Historical Review (Oxford University Press) 83 (5): 1351–1352. doi:10.2307/1854869. ISSN 0002-8762. "one of the most respected undergraduate colleges in America.".

- Silverstein, Stuart (6 April 2002). "Pomona College Head to Retire". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-apr-06-me-pomona6-story.html. "prestigious liberal arts school"

- Wallace, Amy (22 May 1996). "Claremont Colleges: Can Bigger Be Better?". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1996-05-22-mn-7046-story.html. "Considered one of the finest liberal arts institutions in the nation"

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Glynn, Jennifer (September 2017). "Opening Doors: How Selective Colleges and Universities Are Expanding Access for High-Achieving, Low-Income Students". Jack Kent Cooke Foundation. https://www.jkcf.org/research/opening-doors-how-selective-colleges-and-universities-are-expanding-access-for-high-achieving-low-income-students/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Greene & Greene 2016, p. 550.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Fiske 2021, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Top Colleges Doing the Most for the American Dream". The New York Times. 25 May 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/05/25/sunday-review/opinion-pell-table.html.

- ↑

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Hermes, J.J. (October 26, 2007). "In California, 2 Small Colleges Abound in Fulbright Scholars". The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/in-california-2-small-colleges-abound-in-fulbright-scholars/.

- ↑ "Exterior view of Pomona College, Claremont, 1907". University of Southern California. http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll65/id/26148.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "1893" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1890s/1893.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Lyon 1977, chpt. 1.

- ↑ "1887" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1880s/1887.

- ↑ Rudolph, Frederick (1962). The American College & University: A History. Athens, Georgia: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-1284-3.

- ↑ "1885". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1880s/1885.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 "1888" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1880s/1888.

- ↑ "1906" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1900s/1906.

- ↑ Bright, William (1998). 1500 California Place Names: Their Origin and Meaning. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-520-92054-5.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Lyon 1977, chpt. 2.

- ↑ "1890" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1890s/1890.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 40.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 "1894" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1890s/1894.

- ↑ "1903" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1900s/1903.

- ↑ "1895" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1890s/1895.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, chpt. 3.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Harth 2007.

- ↑ Hua, Vanessa (July 2, 2012). "To Shine in the West". Pomona College Magazine (Pomona College). https://magazine.pomona.edu/2012/summer/to-shine-in-the-west/.

- ↑ Desai, Saahil (5 February 2016). "The Erasure of Winston M.C. Dickson, Pomona's First Black Graduate". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/life-style5420/.

- ↑ Hong, Peter Y. (2003-04-10). "College Diversity Feared at Risk". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2003-apr-10-me-private10-story.html.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, pp. 83–85.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "1905" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1900s/1905.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 135.

- ↑ "1911" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1910s/1911.

- ↑ "1912" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1910s/1912.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 136.

- ↑ "1913" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1910s/1913.

- ↑ Colcord, D. Herbert (1914). "Pomona College". The Phi Beta Kappa Key (Phi Beta Kappa) 2 (4): 171–173. ISSN 2373-0331. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42913539.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, pp. 142–144.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 215.

- ↑ "1921" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1920s/1921.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, pp. 42–44.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 "1900" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1900s/1900.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 "1947" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1940s/1947.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 168.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 178.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "1916" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1910s/1916.

- ↑ "1917" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1910s/1917.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 "1943" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1940s/1943.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, chpt. 14.

- ↑ Blackstock, Joe (8 October 2012). "Blaisdell's goal was to make sure the Claremont Colleges would expand, but remain small". Inland Valley Daily Bulletin. https://www.dailybulletin.com/2012/10/08/blaisdells-goal-was-to-make-sure-the-claremont-colleges-would-expand-but-remain-small/.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 239.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 "A Brief History of Pomona College". Pomona College. March 19, 2015. https://www.pomona.edu/about/brief-history-pomona-college.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, chpt. 16.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 "1928" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1920s/1928.

- ↑ "1929" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1920s/1929.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, pp. 312–314.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, chpt. 17.

- ↑ "1932" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1930s/1932.

- ↑ "1934" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1930s/1934.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 "1941" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1940s/1941.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 "1942" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1940s/1942.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 "1944" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1940s/1944.

- ↑ Barber, Mary (30 Apr 1987). "They Weathered the Winds of War | Special Cadets Meet Again After 43 Years" (in en). Los Angeles Times: p. 245. https://latimes.newspapers.com/clip/80823913/they-weathered-the-winds-of-war-special/.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, chpt. 20.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, pt. 3.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 413.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, chpt. 24.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 "1958" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1950s/1958.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, pp. 430–431.

- ↑ Stanley, Peter W. (1997). "Chapter 5: Successful Fund Raising at a Small Private Liberal Arts College: Pomona College". in Rhodes, Frank H. T.. Successful Fund Raising for Higher Education: The Advancement of Learning. Phoenix, Arizona: American Council on Education and Oryx Press. ISBN 978-1-57356-072-6. https://archive.org/details/successfulfundra0000unse.

- ↑ Sterman, Paul (14 November 2012). "The Man with a Plan". Pomona College. https://pomonaplan.pomona.edu/manwithplan.php.

- ↑ "Pomona Plan Book 2017". Pomona College. https://pomonaplan.pomona.edu/pdf/Pomona Plan Book 2017.pdf.

- ↑ "Profiles of the 6 Claremont Colleges and How They Grew". Los Angeles Times. 15 November 1987. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-11-15-ga-21123-story.html.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "1957" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1950s/1957.

- ↑ Desai, Saahil; Tidmarsh, Kevin (26 April 2016). "Farewell To Pomona". Hidden Pomona (Podcast). Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ↑ Breslow, Samuel (15 February 2017). "Ye Olde Student Life: Pomona Rebels Against Japanese Internment". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/life-style6401/.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 556.

- ↑ Kendall, Mark. "Fisk and Pomona". Pomona College Magazine (Pomona College) (Fall 2011): p. 4. http://magazine.pomona.edu/wp-content/uploads/images/pdf/2011-fall.pdf#page=4.

- ↑ "1952" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1950s/1952.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 "1968" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1960s/1968.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, pp. 560–561.

- ↑ "1967" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1960s/1967.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Stein, Harry (5 April 2016). "How My Friends and I Wrecked Pomona College" (in en). City Journal (Manhattan Institute for Policy Research). https://www.city-journal.org/html/how-my-friends-and-i-wrecked-pomona-college-14331.html.

- ↑ Houston, Paul (22 Feb 1968). "Students Compel Air Force to Halt Recruiting at Pomona College" (in en). Los Angeles Times: pp. 3, 35. https://latimes.newspapers.com/clip/80790586/students-compel-air-force-to-halt/.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, pp. 565–566.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 "1969" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1960s/1969.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 568.

- ↑ Desai, Saahil; Tidmarsh, Kevin (26 February 2016). "When Carnegie Was Bombed". Hidden Pomona (Podcast). Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ↑ "David Alexander". Los Angeles Times. 27 July 2010. https://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-me-adv-passings-20100726-story.html. "David Alexander, 77, who brought national standing to Pomona College during a two-decade tenure as president, died Sunday"

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 "1984" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1980s/1984.

- ↑ Chang, Irene (22 November 1990). "Pomona College Hears Call From Asians for More Ethnic Programs". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1990-11-22-ga-6877-story.html.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 "About the College". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7544.

- ↑ "Campus Life: Pomona; Fraternity Rooms To Be Converted Into Lounges". The New York Times. March 24, 1991. https://www.nytimes.com/1991/03/24/nyregion/campus-life-pomona-fraternity-rooms-to-be-converted-into-lounges.html.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Johnson, Nate. "Frats with a Difference" (in en). Pomona College Magazine (Pomona College) (Spring 2001). http://www.pomona.edu/Magazine/PCMSP01/frats.shtml.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 "Pomona College's Studio Art Hall Wins National Steel Building Award". American Institute of Steel Construction. November 4, 2015. https://www.aisc.org/newsdetail.aspx?id=41122.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Hawthorne, Christopher (9 January 2015). "Review: Compelling case for gray at Pomona College's Studio Art Hall". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-ca-pomona-art-building-review-20150111-column.html.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Dunn, Kathryn (May 4, 2017). "David Oxtoby reflects on his 14 years at Pomona College" (in en). Claremont Courier. https://www.claremont-courier.com/education/t23056-oxtoby.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 100.2 "2008" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/2000s/2008.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 "Sustainability timeline" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/sustainability/sustainability-administration/timeline.

- ↑ "2006" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/2000s/2006.

- ↑ Lorin, Janet Frankston (25 August 2009). "Endowment Losses Threaten No-Loan Policies as Guarantees Vanish" (in en). Bloomberg News. http://philanthropynewsdigest.org/news/some-colleges-re-evaluating-no-loan-financial-aid-packages.

- ↑ Marso, Larry (16 April 1982). "Need-Blind Admissions Policy Strains Budget". The Student Life.

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Felton, Emmanuel (23 December 2015). "How elite private colleges might serve black students better". The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/how-elite-private-colleges-might-serve-black-students-better/.

- ↑ Gordon, Larry (17 December 2008). "College restores its alma mater". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2008-dec-17-me-briefs17.s4-story.html.

- ↑ Woods, Mark. "A Time to Sing" (in en). Pomona College Magazine (Pomona College) (Winter 2009): pp. 6–7. https://magazine.pomona.edu/wp-content/uploads/images/pdf/2009-winter.pdf#page=6.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Medina, Jennifer (February 1, 2012). "Immigrant Worker Firings Unsettle Pomona College". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/02/us/after-workers-are-fired-an-immigration-debate-roils-california-campus.html.

- ↑ Pope, Laney (2 March 2018). "Pomona's DACA Advocacy Contrasts With 2011 Firing Of Undocumented Workers". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/news7366/.

- ↑ Zalesin, Jeff (2 December 2011). "17 Employees Terminated Over Documents; Boycott, Vigil Extended". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/news573/.

- ↑ Haas, Wes (3 May 2013). "WFJ Votes to Unionize". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/news3203/.

- ↑ Rivera, Carla (1 May 2013). "Pomona College dining hall workers vote to unionize". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-xpm-2013-may-01-la-me-ln-college-workers-20130501-story.html.

- ↑ Breslow, Samuel (29 April 2016). "Looking Back On Pomona's Rebranding". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/news5908/.

- ↑ Watanabe, Teresa (10 October 2015). "Pomona College failed to properly handle sex abuse cases, complaint alleges". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-pomona-sex-assault-20151009-story.html.

- ↑ Yarbrough, Beau (8 December 2017). "Pomona College protesters blast school's handling of sexual assault complaints". Inland Valley Daily Bulletin. https://www.dailybulletin.com/2017/12/07/pomona-college-protesters-blast-schools-handling-of-sexual-assault-complaints/.

- ↑ Marcotte, Amanda (5 June 2015). "Pomona College Does Damage Control After a Sexual Assault Protest. Will Its New Policies Help Victims?" (in en). Slate. https://slate.com/human-interest/2015/06/pomona-college-does-damage-control-after-a-sexual-assault-protest-but-one-new-policy-may-actually-help-victims.html.

- ↑ Clauer, Haidee (16 November 2018). "Survey on campus sexual assault occurrence raises concerns, sparks conversation". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/survey-on-campus-sexual-assault-occurrence-raises-concerns-sparks-conversation/.

- ↑ "The Office of President G. Gabrielle Starr". https://www.pomona.edu/new-president.

- ↑ Rod, Marc (October 18, 2017). "G. Gabrielle Starr Inaugurated As 10th President Of Pomona College". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/news6983/.

- ↑ Xia, Rosanna (9 December 2016). "Pomona College's new president will be the first woman and African American to lead the campus". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/local/education/la-me-pomona-college-new-president-20161208-story.html.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Rod, Marc; Browning, Kellen; Snowdon, Hank; Heeter, Maria; Davidoff, Jasper (2020-03-11). "Claremont Colleges cancel in-person classes, tell students to go home". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/coronavirus-covid-19-classes-canceled-online-claremont/.

- ↑ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Information for the Pomona College Community" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/coronavirus.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 123.2 123.3 123.4 123.5 123.6 123.7 123.8 "Pomona College 2015 Master Plan". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/sites/default/files/pomona_master_plan.pdf.

- ↑ Carney, Steve (11 January 2019). "Neighborhood Spotlight: Claremont owns its lettered and leafy college-town vibe". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/business/realestate/hot-property/la-fi-hp-neighborhood-spotlight-claremont-20190112-story.html.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 "Maps". City of Claremont. https://www.ci.claremont.ca.us/about-us/city-profile/maps.

- ↑ "Climate". Bernard Field Station. http://bfs.claremont.edu/environment/bfsclime.html.

- ↑ "Geology & Geography". Bernard Field Station. http://bfs.claremont.edu/environment/bfsgeo.html.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, chpt. 3–5.

- ↑ Anderson, Seth (December 14, 2007). "James Blaisdell and the Claremont Colleges". Claremont Graduate University. http://claremontconversation.org/tcourse/tndy4010/page/James+Blaisdell-The+Visionary.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 Sutton, Frances (2020-10-02). "Framed: A love letter to Pomona's campus" (in en-US). https://tsl.news/pomona-campus-art-column/.

- ↑ 131.00 131.01 131.02 131.03 131.04 131.05 131.06 131.07 131.08 131.09 131.10 131.11 131.12 131.13 131.14 131.15 "Campus Map". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/map/.

- ↑ Peters, Cynthia (September 21, 2011). "Pomona College Celebrates Opening of Two of the Nation's Greenest Residence Halls". Pomona College. http://www.pomona.edu/news/2011/09/21-residence-hall-opening.aspx.

- ↑ "Campus Facilities". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7548.

- ↑ "Building Address List" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/facilities-campus-services/offices/mail/building-address-list.

- ↑ "Mudd-Blaisdell Hall, Frank Dining and Seaver Theatre Complex". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/map/?id=523#!t/819:2.

- ↑ "LEED Certified Buildings" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/sustainability/facilities/leed-certified-buildings.

- ↑ Breslow, Samuel (2015-10-09). "Pomona's Turf Removal Reaches Nearly All Corners of Campus" (in en-US). https://tsl.news/news5068/.

- ↑ "Pomona on Path to Carbon Neutrality" (in en). Pomona College. 2017-09-07. https://www.pomona.edu/news/2017/09/07-pomona-path-carbon-neutrality.

- ↑ "2018 Sustainable Campus Index". Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education. https://www.aashe.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/SCI-2018.pdf.

- ↑ "Residence Halls – South Campus". Pomona College. http://www.pomona.edu/adwr/campuslife/residentiallife/southcampus.shtml.

- ↑ "Oldenborg "The Borg" Center – Pomona College". Pomona College. http://www.pomona.edu/about/pomoniana/oldenborg-center.aspx.

- ↑ "About Bridges Auditorium" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/bridges-auditorium/about.

- ↑ Harth 2007, pp. 100–103.

- ↑ "Bridges Hall of Music" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/academics/departments/music-department/facilities/bridges-hall-music.

- ↑ Heeter, Maria (25 September 2019). "New Pomona art museum set to open fall 2020". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/new-pomona-art-museum-benton/.

- ↑ "Collections" (in en). Benton Museum of Art. 2 October 2014. https://www.pomona.edu/museum/collections.

- ↑ Vankin, Deborah (27 February 2019). "Southern California's newest art museum will be called the Benton". Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cm-pomona-college-benton-art-museum-20190226-story.html.

- ↑ "Byron Dick Seaver Theatre Complex" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/academics/departments/theatre/facilities-locations.

- ↑ "Pomona Profile". Pomona College. http://www.pomona.edu/about/facts-and-figures/pomona-profile.aspx.

- ↑ Fitz, Allison (14 February 2020). "New Rains Center to be completed by 2022; 5Cs prepare for construction's effects". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/new-rains-center-to-be-remodeled/.

- ↑ "1914" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1910s/1914.

- ↑ Guan, Michelle (27 April 2012). "Pomona Chooses Student Speakers for Class Day, Commencement". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/news2294/.

- ↑ "Campus Facilities". Pomona College. http://pomona.catalog.acalog.com/content.php?catoid=33&navoid=6714.

- ↑ Tyack, Nicholas (Fall 2014). "Ralph Cornell and the "College in a Garden"". Eden (California Garden & Landscape History Society) 17 (4). https://cglhs.org/resources/Documents/Eden-17.4-Fa-2014.pdf. Retrieved 19 August 2020.

- ↑ 155.0 155.1 Weber, Jamie (May 17, 2018). "Solving the Mystery of Clark I-III-V". Pomona College Magazine (Pomona College). http://magazine.pomona.edu/pomoniana/2018/05/17/the-mystery-of-clark-i-iii-v-solved/.

- ↑ "1983" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1980s/1983.

- ↑ "1964" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1960s/1964.

- ↑ "Richard C. Seaver Biology Building" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/academics/departments/biology/facilities/richard-c-seaver-biology-building.

- ↑ Kendall, Mark (1 January 2008). "Night Rite". Pomona College Magazine (Pomona College). https://www.pomona.edu/news/2008/01/01-night-rite.

- ↑ "Dedication Held For Turrell Skyspace Exhibition". The Student Life. http://www.tsl.pomona.edu/index.php?article=2669.

- ↑ Scott, David W. (Fall 1957). "Orozco's Prometheus: Summation, Transition, Innovation". Art Journal 17 (1): 2–18. doi:10.2307/773653.

- ↑ Davidson, Martha (Spring 1962). "Rico Lebrun Mural at Pomona". Art Journal 21 (3): 143–175. doi:10.2307/774410.

- ↑ Peters, Cynthia (July 24, 2012). "Pomona College Buys Trails End Ranch For New Field Station with Plans to Preserve the 50 Wilderness Acres". Pomona College. http://www.pomona.edu/news/2012/07/24-trails-end-ranch-purchase.aspx.

- ↑ "Trails End Ranch" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/dining/catering/trails-end-ranch.

- ↑ "The Mildred Pitt Ranch" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/academics/departments/biology/facilities/mildred-pitt-ranch.

- ↑ "Halona Lodge and Retreat Center" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/outdoor-education-center/connect-nature/halona-lodge-and-retreat-center.

- ↑ "1931" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1930s/1931.

- ↑ "Table Mountain Observatory" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/academics/departments/physics-and-astronomy/facilities/table-mountain-observatory.

- ↑ "About the Bernard Field Station". Bernard Field Station. http://bfs.claremont.edu/overview.html.

- ↑ 170.0 170.1 170.2 170.3 170.4 "Bylaws of Pomona College". Pomona College. May 13, 2017. https://www.pomona.edu/sites/default/files/bylaws-of-pomona-college.pdf.

- ↑ Fiske 2021, p. 155.

- ↑ Starr, G. Gabrielle (18 May 2018). "Task Force on Public Dialogue Final Report and Board Update" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/president/statements/posts/task-force-public-dialogue-final-report-and-board-update.

- ↑ 173.0 173.1 "Campus Life". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7547.

- ↑ 174.0 174.1 174.2 Fiske 2021, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ "The Claremont Colleges Services". The Claremont Colleges. https://services.claremont.edu/.

- ↑ Carlson, Scott (11 February 2013). "Tough Times Push More Small Colleges to Join Forces". The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/tough-times-push-more-small-colleges-to-join-forces/.

- ↑ Lyon 1977, p. 381.

- ↑ 178.0 178.1 Fiske 2021, p. 146.

- ↑ Maley, Megan; Kim, Kaylin (20 November 2020). "An in-depth look into the 5Cs' endowments". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/the-claremont-colleges-endowment-explained/.

- ↑ "568 Presidents Group Member Institutions". 568 Group. http://www.568group.org/home/?q=node/24.

- ↑ "Institutions Archive". Consortium of Liberal Arts Colleges. https://www.liberalarts.org/members/.

- ↑ "Oberlin Group Institution Members". Oberlin Group. https://www.oberlingroup.org/group-members.

- ↑ "Members" (in en). Annapolis Group. https://www.annapolisgroup.org/members.

- ↑ "WASC Senior College and University Commission" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/wscuc.

- ↑ "Pomona College". WASC Senior College and University Commission. https://www.wscuc.org/institutions/pomona-college.

- ↑ U.S. and Canadian 2020 NTSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2020 Endowment Market Value, Percentage Change in Market Value from FY19 to FY20, and FY20 Endowment Market Values Per Full-time Equivalent Student (Report). National Association of College and University Business Officers and Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America. April 22, 2021. https://www.nacubo.org/-/media/Documents/Research/2020-NTSE-Endowment-Market-Values-REVISED-APRIL-22-2021.ashx. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ↑ Breslow, Samuel (2 February 2018). "GOP Bill Hits Pomona, CMC With Endowment Tax". The Student Life. https://tsl.news/news7186/.

- ↑ "Fitch Rates Pomona College, CA's Revs at 'AAA'; Outlook Stable". Fitch Ratings. 12 October 2020. https://www.fitchratings.com/research/us-public-finance/fitch-rates-pomona-college-ca-revs-at-aaa-outlook-stable-12-10-2020.

- ↑ 189.0 189.1 "Academics at Pomona". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7539.

- ↑ "1902" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/timeline/1900s/1902.

- ↑ 191.0 191.1 "Enrollment Policies". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7479.

- ↑ "Degree Requirements". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7470.

- ↑ "Majors and Minors". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7498.

- ↑ "Completed Majors" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/institutional-research/information-center/completed-majors.

- ↑ "Majors and Minors". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/office-registrar/reports-and-statistics/majors-and-minors.

- ↑ "Academic Life at Pomona College" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/new-students/guide/academic-life.

- ↑ "Pre-Professional Education". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7466.

- ↑ 198.0 198.1 "Cooperative Academic Programs". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7465.

- ↑ 199.0 199.1 "Fact Sheet". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/about/fact-sheet.

- ↑ "The Claremont Colleges". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/about/claremont-colleges.

- ↑ "Independent Study". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7483.

- ↑ "Our Curriculum" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/academics/about-our-liberal-arts-education/our-curriculum.

- ↑ 203.00 203.01 203.02 203.03 203.04 203.05 203.06 203.07 203.08 203.09 203.10 203.11 203.12 "Common Data Set 2020–2021". Pomona College. https://pomona.app.box.com/s/k8qpfrh6ejqu1osgevg46hz6wnkyv0ul.

- ↑ Yee 2014, p. 345.

- ↑ "Reading Days". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7487.

- ↑ Brown, Travis (Summer 2014). "The Quantitative Skills Center at Pomona College: Year One Review". Peer Review (Association of American Colleges and Universities) 16 (3). https://www.aacu.org/peerreivew/2014/summer/brown. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- ↑ "Quantitative Skills Center" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/quantitative-skills-center.

- ↑ "Pomona College's Writing Center Receives $250,000 Grant to Support Written, Oral and Visual Literacies" (in en). Pomona College. 2019-07-31. https://www.pomona.edu/news/2019/07/31-pomona-colleges-writing-center-receives-250000-grant-support-written-oral-and-visual-literacies.

- ↑ "Foreign Language Resource Center" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/foreign-language-resource-center.

- ↑ 210.0 210.1 210.2 "Institutional Research Fast Facts". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/institutional-research/information-center/fast-facts.

- ↑ "Research at Pomona" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/research.

- ↑ "Research Opportunities". Pomona College. https://catalog.pomona.edu/content.php?catoid=37&navoid=7464.

- ↑ Davidoff, Jasper (2020-04-01). "Pomona College suspends summer student research program" (in en-US). https://tsl.news/pomona-college-suspends-summer-research-program/.

- ↑ "About the Humanities Studio" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/humanities-studio/about.

- ↑ "About the Pacific Basin Institute" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/pacific-basin-institute/about.

- ↑ "Study Abroad". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/study-abroad.

- ↑ "Pomona College Internship Program (PCIP): Semester" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/career-development/job-internship-search/pcip/semester.

- ↑ "Pomona College Internship Program (PCIP): Summer Experience, International & Domestic" (in en). Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/career-development/job-internship-search/pcip/summer-experience-international-domestic.

- ↑ 219.0 219.1 219.2 "Where Do Grads Go '15–'16". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/sites/default/files/cdo-annual-report-2015-2016.pdf.

- ↑ "Freshman Retention Rate | National Liberal Arts Colleges". https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/rankings/national-liberal-arts-colleges/freshmen-least-most-likely-return.

- ↑ "Highest 4-Year Graduation Rates". U.S. News & World Report. https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/rankings/highest-grad-rate. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- ↑ "Doctorates Awarded". National Science Foundation. http://www.swarthmore.edu/institutional-research/doctorates-awarded.

- ↑ Belasco, Andrew; Bergman, Dave; Trivette, Michael (May 15, 2021). Colleges Worth Your Money (2nd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4758-5964-5.

- ↑ "After Pomona". https://www.pomona.edu/after-pomona.

- ↑ "Where Do Grads Go?". Pomona College. https://www.pomona.edu/administration/career-development/where-grads-go.

- ↑ "Current Professional Activities of Pomona Alumni". Pomona College. https://tableau.campus.pomona.edu/views/ProfessionalActivitiesPublic/TopIndustries?iframeSizedToWindow=true&:embed=y&:display_spinner=no&:showAppBanner=false&:embed_code_version=3&:loadOrderID=0&:display_count=n&:showVizHome=n&:origin=viz_share_link.

- ↑ "Salaries for Pomona College Graduates". PayScale. https://www.payscale.com/research/US/School=Pomona_College/Salary.

- ↑ "The "Hot" Top 10 Most Churchill Scholars (Last 10 Years)". Churchill News (Winston Churchill Foundation of the United States): 6. http://www.winstonchurchillfoundation.org/publications/AutumnNewsletter2015.pdf?page=6. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ↑ "Top Producers of Fulbright U.S. Scholars and Students, 2020–21". The Chronicle of Higher Education. February 15, 2021. https://www.chronicle.com/article/top-producers-of-fulbright-u-s-scholars-and-students-2020-21.