Black Hills

From Nwe

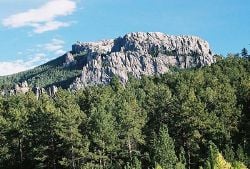

From Nwe The Black Hills are a small, isolated mountain range rising from the Great Plains of North America in western South Dakota and extending into northeastern Wyoming, USA. Set off from the main body of the Rocky Mountains, the region is something of a geological anomaly—accurately described as an "island of trees in a sea of grass." The Black Hills encompass the Black Hills National Forest and are home to the tallest peaks of continental North America east of the Rockies.

The Hills, which cover an area 125 miles long and 65 miles wide, include a great variety of terrain in the form of canyons and gulches, rugged rock formations, open grassland, streams, lakes, and unique caves. [1]

The name "Black Hills" is a translation of the Lakota Paha Sapa, which literally mean "hills that are black." The pine-covered hills, which rise several thousand feet above the surrounding prairie, appear black from a distance.

Native Americans have a long history in the Black Hills, which they consider sacred. The Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1868 specified the area of the Great Sioux Reservation to be all of South Dakota west of the Missouri River and additional territory in adjoining states. This included the Black Hills. The treaty stipulated that the land was to be

- "set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation" of the Lakota.

However, after gold was discovered, the U.S. Government violated the treaty and took control of the region. The area remains under dispute nearly 150 years later. Though the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in 1980 that the Black Hills were illegally taken and the Lakota must receive remuneration of the initial offering price plus interest; the Lakota refused the settlement, demanding instead the return of the Black Hills.

Overview

Roughly 100 square miles in area, the Black Hills rise from the prairies in a deep blue hue. The pine-covered slopes of the range, appearing black from a distance, are a striking contrast to the light colored prairie grasses of the surrounding foothills. For centuries, people have been fascinated with the Black Hills.

Known as He Sapa, or more commonly Paha Sapa, in the Lakota language, the Black Hills are considered sacred to the Native Americans. The Sioux believe the area to be the beginning point of their people and thus the center of their universe. This is the homeland they returned to in the 1700s and which has served them as a hunting ground and sacred territory.

Prior to explorations by the La Verendrye brothers in 1742, many tribes frequented the Black Hills including Ponca, Kiowa Apache, Arapaho, Kiowa and Cheyenne for at least the past 10,000 years. The mountains and other key features in and around the Black Hills and what is now within the Black Hills National Forest were considered sacred to indigenous peoples and many came here on vision quests, for hunting and for trade.

The Black Hills are home to an amazing diversity of nature. Exposed granite and limestone outcroppings provide dramatic glimpses of the core of the Hills in many areas. There is an abundance of lakes, streams and warm springs in the midst of a great variety of vegetation and wildlife.

The Black Hills are home to Mount Rushmore, Wind Cave National Park, Jewel Cave National Monument, Harney Peak (the highest point between the Rockies and the French Alps), Custer State Park (the largest state park in South Dakota, and one of the largest in the US), Bear Butte State Park, Devils Tower National Monument, and the Crazy Horse Memorial (the largest sculpture in the world).

The historic town of Deadwood and the Homestake Mine (the largest and deepest mine in the Western Hemisphere) are in the Black Hills. The Badlands are just east of the Hills. The Black Hills also hosts the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally each August. Begun in 1940, the 65th Rally in 2005 saw more than 550,000 bikers visit the Black Hills; the rally is a key part of the regional economy.

Historic figures related to the area include Crazy Horse, Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, Wild Bill Hickok, George Armstrong Custer, and Gutzon Borglum and Korczak Ziolkowski (sculptors of Mount Rushmore & the Crazy Horse Memorial, respectively). [2]

Geology

The geology of the Black Hills is complex. A Tertiary mountain-building episode is responsible for the uplift and current topography of the Black Hills region. This uplift was marked by volcanic activity in the northern Black Hills. The southern Black Hills are characterized by Precambrian granite, pegmatite, and metamorphic rocks that comprise the core of the entire Black Hills uplift. This core is rimmed by Paleozoic, Mesozoic, and Cenozoic sedimentary rocks. The stratigraphy of the Black Hills is laid out very much like a target as it is an oval dome, with rings of different rock types dipping away from the center.

Precambrian

The 'bulls eye' of this target is called the granite core. The granite of the Black Hills was emplaced by magma generated during the Trans-Hudsonian orogeny and contains abundant pegmatite. The core of the Black Hills has been dated to 1.8 billion years. There are other localized deposits that have been dated to around 2.2 to 2.8 billion years. One of these is located in the northern hills and is called Elk Creek Granite though it has been metamorphosed into gneiss. The other is called the Bear Mountain complex and is located in the west central part of the hills.

Making a concentric ring around the core is the metamorphic zone. The rocks in this ring are all very old, as much as 2.0 billion years and older. This zone is very complex, filled with many diverse rock types. The rocks were originally sedimentary rocks until there was a collision between the North American continent and a terrane. This collision, called the Trans-Hudsonian Orogeny, caused the original rocks to fold and twist into a vast mountain range. Over the millions of years these tilted rocks, which in many areas are tilted to 90 degrees or more, eroded. Today we see the evidence of this erosion in the Black Hills, where the metamorphic rocks end in an angular unconformity below the younger sedimentary layers.

Paleozoic

The final layers of the Black Hills consist of sedimentary rocks. The oldest of which lies on top of the metamorphic layers at a much shallower angle. This rock called the Deadwood Formation is mostly sandstone and was the original source of gold found in the Deadwood area. Above the Deadwood Formation lies the Englewood Formation and Paha Sapa limestone which is the source of the more than 200 caves found in the Black Hills, including Jewel Cave and Wind cave. The Minilusa Formation is next and is composed of highly variable sandstones and limestones followed by the Opeche shale and the Minnikata limestone.

Mesozoic

The next rock layer, the Spearfish Formation, forms a valley around the hills called the red valley. It is mostly a red shale with beds of gypsum. These shale and gypsum beds as well as the nearby limestone beds of the Minnikata are used in the manufacture of cement at a cement plant in Rapid City. Next is the shale and sandstone Sundance Formation which is topped by the Morrison Formation and the Unkpapa sandstone.

The outermost feature of the dome stands out as a hogback ridge. This ridge is made of the Lakota Formation and the Fallriver sandstone which are collectively called the Inyan Kara Group. Above this the layers of rocks are less distinct and are all mainly grey shale with three exceptions, the Newcastle sandstone, the Greenhorn limestone which contains many shark teeth fossils, and the Niobrara Formation which is composed mainly of chalk. These outer ridges are called cuestas.

Cenozoic

The preceding layers were deposited in a horizontal manner. All of them can be seen in core samples and well logs from the flattest parts of the Great Plains. It took a period of uplift to bring them to their present topographical levels in the Black Hills. This uplift called the Laramide orogeny began around the beginning of the Cenozoic and left a line of igneous rocks through the northern hills superimposed on the rocks already discussed. This line extends from Bear Butte in the east to Devils Tower in the west. Evidence of Cenozoic volcanic eruptions, if this happened, has long since been eroded away.

The Black Hills also has a 'skirt' of gravel covering it in areas called erosional terraces. Formed as the waterways cut down into the uplifting hills, they represent the former locations of today's rivers. These beds are generally around 10,000 years old or younger judging by the artifacts and fossils found. There are a few places mainly in the high elevations where older, as old as 20 million years according to camel and rodent fossils found, gravels have been found but for the most part these older beds have been eroded away.

Biosystems

As with the geology, the biology of the Black Hills is complex. Most of the Hills are a fire-climax Ponderosa Pine forest, with Black Hills Spruce (Picea glauca var. densata) occurring in cool moist valleys of the Northern Hills. Oddly, this endemic variety of spruce does not occur in the moist Bear Lodge Mountains, which make up most of the Wyoming portion of the Black Hills. Large open parks (mountain meadows) with lush grassland rather than forest are scattered through the Hills (especially the western portion), and the southern edge of the Hills, due to the rainshadow of the higher elevations, are covered by a dry pine savannah, with stands of Mountain Mahogany and Rocky Mountain Juniper. Wildlife is both diverse and plentiful.

Black Hills creeks are known for their trout, while the forests and grasslands offer good habitat for American Bison, White-tailed and Mule Deer, Pronghorn, Bighorn Sheep, mountain lions, and a variety of smaller animals, such as prairie dogs, Yellow-bellied Marmots, and Red Squirrels. Biologically, the Black Hills is a meeting and mixing place, with species common to regions to the east, west, north, and south. The Hills do however, support some endemic taxa, the most famous of which is probably White-winged Junco (Junco hyemalis aikeni).

History

Native Americans have inhabited the area of the Black Hills since at least 7000 B.C.E. The Arikara arrived by 1500 C.E., followed by the Cheyenne, Crow, Kiowa and Pawnee. The Lakota arrived from Minnesota in the eighteenth century, driving out the other tribes. Paha Sapa, as the Hills were known to the Lakota Sioux, were considered sacred territory where they believe life began. The western bands of Sioux used the Hills as hunting grounds.

The Sioux controlled the northern Plains, including the Black Hills, throughout most of the nineteenth century. A series of treaties with the U.S. Government were entered into by the Allied Lakota bands at Fort Laramie, Wyoming, in 1851 and 1868. The terms of the treaty of 1868 specified the area of the Great Sioux Reservation to be all of South Dakota west of the Missouri River and additional territory in adjoining states and was to be "set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation" of the Lakota.[3] Further, "No white person or persons shall be permitted to settle upon or occupy any portion of the territory, or without the consent of the Indians to pass through the same." [4]

Although whites were to be excluded from the reservation, after the public discovery of gold in the 1870s, the conflict over control of the region sparked the last major Indian War on the Great Plains, the Black Hills War. Yielding to the demands of prospectors, in 1874 the U.S. government dispatched troops into the Black Hills under General George Armstrong Custer in order to establish army posts. The Sioux responded to this intrusion militarily.

During the 1875–1878 gold rush, thousands of miners went to the Black Hills; in 1880, the area was the most densely populated part of Dakota Territory. There were three large towns in the Northern Hills: Deadwood, Central City, and Lead. Around these lay groups of smaller gold camps, towns, and villages. Hill City and Custer City sprang up in the Southern Hills, and railroads were already reaching the previously remote area. From 1880 on, the gold mines yielded about $4,000,000 annually, and the silver mines about $3,000,000 annually.

The government had offered to purchase the land from the Tribe, but considering it sacred, they refused to sell. In response, the government demanded that all Indians who left the reservation area (mainly to hunt buffalo) report to their agents; few complied. The U.S. Army did not keep miners off Sioux (Lakota) hunting grounds; yet, when ordered to take action against bands of Sioux hunting on the range, according to their treaty rights, the Army moved vigorously. On June 25, 1876, after several indecisive encounters, General Custer found the main encampment of the Lakota and their allies at the Little Bighorn River. Custer and his men — who were separated from their main body of troops — were all killed by the far more numerous Indians who had the tactical advantage. They were led in the field by Crazy Horse and inspired by Sitting Bull's earlier vision of victory. This has come to be known as the "Battle of the Little Bighorn."

Outraged, the U.S. took control of the region from the Lakota in violation of the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868). The year after the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Congress passed legislation that opened the Black Hills to white occupation. Under the terms of the new treaty, drawn in 1877, the Sioux were forced to cede the Black Hills for a fraction of their value, and the area was opened to the gold miners. The Indians never accepted the validity of this purchase, and the area remains under dispute to this day.

Demanding redress for the Black Hills illegal seizure, throughout the twentieth century a number of cases were filed against the U.S. government by the Lakota tribe. In 1946 Congress created the Indian Claims Commission as a body to address outstanding land disputes. The ICC judged in 1975 that Congress's 1877 actions had been unconstitutional and amounted to an illegal seizure of Indian Lands. It was determined that the tribe was entitled to the 1877 estimated value of the seized lands, roughly 17.1 million dollars, plus interest. The U.S. government appealed, and in United States v. Sioux Nation, the Supreme Court upheld the ICC ruling. [5]

On July 23, 1980, in the case of United States v. Sioux Nations of Indians, 448 U.S. 371, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the Black Hills were illegally taken and that remuneration of the initial offering price plus interest — nearly $106 million — be paid.[6] The Lakota refused the settlement, demanding instead the return of the Black Hills. The money remains in an interest-bearing account which now amounts to over $1 billion,[7] and in spite of their poverty the Lakota still refuse to bend, reasoning that "One does not sell the earth upon which the people walk." - Crazy Horse (Tashunka Witko).[8]

Tourism and economy

Today the Black Hills functions in many ways as a very spread-out urban area with a population of 250,000. The major city is Rapid City, with an incorporated population of over 70,000 and a metropolitan population of 125,000. It serves a market area covering much of five states: North and South Dakota, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana.

In addition to tourism and mining (including coal, specialty minerals, and the now declining gold mining), the Black Hills economy includes ranching (sheep and cattle, primarily, with buffalo and ratites becoming more common), timber (lumber), Ellsworth Air Force Base, and some manufacturing, including jewelry (Black Hills Gold Jewelry), cement, electronics, cabinetry, guns and ammunition.

Other important Black Hills cities include Belle Fourche, a ranching town; Spearfish, home of Black Hills State University; Deadwood, a historic and well-preserved gambling mecca; its twin city of Lead, home of the now-closed Homestake Mine (gold); Keystone, outside Mount Rushmore; Hill City, a timber and tourism town in the center of the Hills; Custer, a mining and tourism town and headquarters for Black Hills National Forest; Hot Springs, an old resort town in the southern Hills; Sturgis, originally a military town (Fort Meade, now a VA center, is located just to the east); and Newcastle, center of the Black Hills petroleum production and refining.

Tourist sites

The Black Hills region is home to a number of important tourist sites, including:

- Mount Rushmore National Memorial, a monumental granite sculpture that represents the first 150 years of the history of the United States with 60-foot sculptures of the heads of former U.S. presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln.

- Wind Cave National Park, established as a National Park in 1903 by President Theodore Roosevelt, it was the seventh U.S. National Park and the first cave to be designated a national park anywhere in the world. Notable for its displays of the calcite formation known as boxwork, approximately 95 percent of the world's boxwork formations are found in Wind Cave. Above ground, the park includes the largest remaining natural mixed-grass prairie in the U.S. The Lakota spoke of a 'hole that blew air', a place they considered sacred as the site where humanity first emerged from the underworld where they lived before the demiurge creation of the world.

- Jewel Cave National Monument contains Jewel Cave, currently the second longest cave in the world, with over 141 miles (225 km) of mapped passageways. It is filled with calcite crystals and other wonders that make up the "jewels" of Jewel Cave National Monument. Located approximately 13 miles west of the Black Hill's town of Custer, it became a national monument in 1908.

- Harney Peak, the highest mountain in South Dakota, is located in the Black Hills National Forest. With an elevation of 7,242 ft (2,207 m), the peak is the highest point east of the Rocky Mountains in mainland North America.

- Black Elk Wilderness area in the center of the Norbeck Wildlife Preserve is a 13,426-acre area designated as protected land by Congress on December 22, 1980. It is named for Black Elk, an Oglala Sioux holy man, and contains Harney Peak. [9]

- Custer State Park is a state park and wildlife reserve within the Black Hills, covering 71,000 acres (287 km²). It is South Dakota's largest and first state park. During the 1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps built miles of roads, laid out parks and campgrounds, and built three dams. A herd of 1500 buffalo roam the land freely. Elk, mule deer, white tailed deer, mountain goats, bighorn sheep, pronghorn antelope, mountain lions, and feral burros also inhabit the park.

- Devils Tower National Monument is a monolithic igneous intrusion or volcanic neck located in the Black Hills near the towns of Hulett and Sundance in northeastern Wyoming, above the Belle Fourche River. It rises dramatically 1267 feet above the surrounding terrain, with the summit is 5112 feet above sea level. It was the first declared U.S. National Monument, established on September 24, 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt. The Monument's boundary encloses an area of 1347 acres.

- Bear Butte State Park was established in 1961. Bear Butte was an important landmark and religious site for the Plains Indians tribes long before Europeans reached South Dakota. It is called Mato Paha, or Bear Mountain, by the Sioux. To the Cheyenne, it is Noahvose, the place where Maheo (God) imparted to Sweet Medicine (a mythical hero) the knowledge from which the Cheyenne derive their religious, political, social, and economic customs. The mountain is sacred to many indigenous peoples, who make pilgrimages to leave prayer cloths and bundles tied to the branches of the trees along the mountain’s flanks. Other offerings are often left at the top of the mountain. The site is associated with various religious ceremonies throughout the year. It is a place of prayer, meditation, and peace.

- Crazy Horse Memorial is a mountain monument in the Black Hills, in the form of Crazy Horse, an Oglala Lakota warrior, riding a horse and pointing into the distance. The memorial consists of the mountain carving (monument), the Indian Museum of North America, and the Native American Cultural center. The monument is being carved out of Thunderhead Mountain on land considered sacred between the towns of Custer and Hill City, in South Dakota. It is roughly 8 miles from Mount Rushmore. Construction of the monument has been in process since 1948 and is still far from completion. When finished, it will be the world's largest sculpture, with final dimensions of 641 feet wide and 563 feet high.

- The Needles are a region of fantastically eroded granite pillars, towers, and spires. The Cathedral Spires and Limber Pine Natural Area, a portion of the Needles containing six ridges of pillars as well as a disjunct stand of limber pine, was designated a National Natural Landmark in 1976. The Needles were the original site proposed for the Mount Rushmore carvings.

The Black Hills also hosts the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, held annually the first full week of August. Begun August 14, 1938, it has been held every year, with exceptions during World War II. The 65th Rally in 2005 saw more than 550,000 bikers visit the Black Hills; the rally is a key part of the regional economy.

The George S. Mickelson Trail is a recently opened multi-use path through the Black Hills. It follows the abandoned track of the historic railroad route between the towns of Edgemont and Deadwood. The train was once the only way to bring supplies to the miners in the Hills. The trail is about 110 miles in length, and is used by hikers, cross-country skiers, and bikers.

Notes

- ↑ USDA Forest Service,Black Hills National Forest Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ↑ Black Hills Visitor Magazine. Paha Sapa - The Black Hills Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ↑ Transcript of Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868) Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ↑ Dee Brown, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West (Owl Books: Henry Holt, . 1970), 273.

- ↑ United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ↑ United States v. Sioux Nation of Indians (1980) Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ↑ Tim Giago, The Black Hills: A Case of Dishonest Dealings The Huffington Post, May 25, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2018.

- ↑ Brown 1970.

- ↑ USDA Forest Service, Black Elk Wilderness Retrieved November 21, 2018.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West. Owl Books: Henry Holt, 1970. ISBN 0805010459

- Lazarus, Edward. Black Hills, White Justice: The Sioux Nation Versus the United States: 1775 to the Present. New York: Harper Collins, 1991. ISBN 006016557X

- Robinson, Charles M. A Good Year to Die: The Story of the Great Sioux War. New York: Random House, 1995. ISBN 0679430253

- Sajna, Mike. Crazy Horse: The Life behind the Legend. New York: John Wiley, 2000. ISBN 0471241822

External links

All links retrieved February 8, 2022.

- Wind Cave Federal Website Wind Cave National Park

- Jewel Cave Federal Website Jewel Cave National Monument

- Mount Rushmore Federal Website Mount Rushmore National Memorial

- 1980 Supreme Court Case: United States v. Sioux Nations of Indians, 448 U.S. 371

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Black_Hills history

- Black_Hills_National_Forest history

- Wind_Cave_National_Park history

- Jewel_Cave_National_Monument history

- Harney_Peak history

- Custer_State_Park history

- Devils_Tower_National_Monument history

- Bear_Butte history

- Crazy_Horse_Memorial history

- Needles_(Black_Hills) history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 02:58:48 | 31 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Black_Hills | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF