Gregory I

From Nwe

From Nwe

| Pope Gregory I | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Birth name | Gregory |

| Papacy began | September 3, 590 |

| Papacy ended | March 12, 604 |

| Predecessor | Pelagius II |

| Successor | Sabinian |

| Born | c. 540 Rome, Italy |

| Died | March 12, 604 Rome, Italy |

Pope St. Gregory I or Gregory the Great (c. 540 – March 12, 604) was pope from September 3, 590, until his death. He is also known as Gregory Dialogus (the Dialogist) in Eastern Orthodoxy because of the Dialogues he wrote. Gregory was one of the last popes not to have changed his name when elected to the papacy.

A senator's son and himself the governor of Rome at 30, Gregory tried the monastery but soon returned to active public life, ending his life and the century as pope. Although he was the first pope from a monastic background, his prior political experiences may have helped him to be a talented administrator, who successfully established the supremacy of the papacy of Rome. He was stronger than the emperors of declining Rome, and challenged the power of the patriarch of Constantinople in the battle between East and West. Gregory regained papal authority in Spain and France, and sent missionaries to England. The realignment of barbarian allegiance to Rome from their Arian Christian alliances shaped medieval Europe. Gregory saw Franks, Lombards, and Visigoths align with Rome in religion.

Organization and diplomacy, not ideas, made him great. But, the bottom line was his conviction grounded on his inner character of gentleness and charity. He was basically tolerant to the Jews, protecting their rights based on law. Gregory is a Doctor of the Church and one of the four great Latin Fathers of the Church (the others being Ambrose, Augustine, and Jerome). Of all popes, Gregory I had the most influence on the early medieval Church. His legacy, however, was not necessarily followed successfully by many of his successors.

Biography

Early life

The exact date of Gregory's birth is uncertain, but is usually estimated to be around the year 540. He was born into a wealthy noble Roman family, in a period, however, when the city of Rome was facing a serious decline in population, wealth, and influence. His family seems to have been devout. Gregory's great-great grandfather had been Pope Felix III. Gregory's father, Gordianus, worked for the Roman Church and his father's three sisters were nuns. Gregory's mother Silvia herself is a saint. While his father lived, Gregory took part in Roman political life and at one point was prefect (governor) of the city. However, on his father's death, he converted his family home, located on a hill just opposite the Circus Maximus, into a monastery dedicated to the apostle, St. Andrew. Gregory himself entered as a monk.

Eventually, Pope Pelagius II ordained him a deacon and solicited his help in trying to heal the Nestorian schism of the Three Chapters in northern Italy. In 579, Pelagius chose Gregory as his apocrisiarius or ambassador to the imperial court in Constantinople.

Confrontation with Eutychius

In Constantinople as the papal envoy, Gregory gained attention by starting a controversy with Patriarch Eutychius of Constantinople, who had published a treatise on the resurrection of the dead, in which he argued that the bodies of the resurrected would be incorporeal. Gregory insisted on their corporeality, just as that of the risen Christ had been. The heat of argument drew the emperor in as judge. Eutychius' treatise was condemned, and it suffered the normal fate of all heterodox texts, of being publicly burnt. On his return to Rome, Gregory acted as first secretary to Pelagius, and was later elected pope to succeed him.

Gregory as pope

Around that time, the bishops in Gaul were drawn from the great territorial families, and identified with them. In Visigothic Spain the bishops had little contact with Rome; in Italy the papacy was beset by the violent Lombard dukes. The scholarship and culture of Celtic Christianity had developed utterly unconnected with Rome, and it was thus from Ireland that Britain and Germany were likely to become Christianized, or so it seemed.

But, when Gregory became pope in 590, that situation started to change. Among his first acts was the writing of a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. He soon showed himself to be an effective administrator who greatly increased the authority and influence of the papacy.

Servant of the servants of God

In line with his predecessors such as Dionysius, Damasus, and Leo the Great, Gregory asserted the primacy of the office of the bishop of Rome. Although he did not employ the term "pope," he summed up the responsibilities of the papacy in his official appellation as "servant of the servants of God." He was famous for his charity works. He had a hospital built next to his house on the Caelian Hill to host poor people for dinner, at his expense. He also built a monastery and several oratories on the site. Today, the namesake church of San Gregorio al Celio (largely rebuilt from the original edifices during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) remembers his work. One of the three oratories annexed, the oratory of St. Silvia, is said to lie over the tomb of Gregory's mother.

Gregory's pontificate saw the development of the notion of private penance as parallel to the institution of public penance. He explicitly taught a doctrine of purgatory, where a soul destined to undergo purification after death because of certain sins could begin its purification in this earthly life through good works, obedience, and Christian conduct.

Gregory's relations with the emperor in the East were a cautious diplomatic stand-off. He is known in the East as a tireless worker for communication and understanding between East and West. Among Gregory's other chief acts as pope is his long letter issued in the matter of the schism of the Three Chapters.

He also undertook the conversion of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, where inaction might have encouraged the Celtic missionaries already active in the north of Britain. He sent Augustine of Canterbury to Kent, and by the time of Gregory's death, the conversion of the king and the Kentish nobles had been accomplished. In Britain, therefore, appreciation for Gregory remained strong even after his death, with him being called Gregorius noster ("our Gregory") by the British. It was in Britain, at a monastery in Whitby, that the first full-length life of Gregory was written, in c.713. Appreciation of Gregory in Rome and Italy itself came later, with his successor Pope Sabinian (a secular cleric rather than a monk) rejecting his charitable moves towards the poor of Rome. In contrast to Britain, the first early vita of Gregory written in Italy was produced by John the Deacon in the ninth century.

Sometimes the establishment of the Gregorian Calendar is erroneously attributed to Gregory the Great; that calendar was actually instituted by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 by way of a papal bull entitled, Inter gravissimas.

Liturgical reforms

In letters, Gregory remarks that he moved the Lord's Prayer (Pater Noster or Our Father) to immediately after the Roman Canon and immediately before the Fraction (i.e., breaking the bread). He also reduced the role of deacons in the Roman liturgy.

Sacramentaries directly influenced by Gregorian reforms are referred to as Sacrementaria Gregoriana. With the appearance of these sacramentaries, the Western liturgy begins to show a characteristic that distinguishes it from Eastern liturgical traditions.

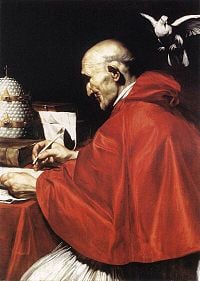

The famous "Gregorian chant" named for him is in fact a misnomer. To honor Gregory, pictures were made to depict the dove of the Holy Spirit perched on Gregory's shoulder, singing God's authentic form of chant into his ear. This gave rise to calling the music "Gregorian chant." A more accurate term is plainsong or plainchant. Gregory was patron saint of choirboys and singers. While he most likely did not invent the Gregorian chant, his image suggests Byzantine influence and Western attitude.

Works

Gregory was hardly a creative theologian. He simply followed and popularized patristic theology, especially Augustinian theology. He was, however, a fertile writer on practical matters. Gregory is the only pope between the fifth and the eleventh centuries whose correspondence and writings have survived enough to form a comprehensive corpus. Included in his surviving works are:

- Sermons (40 on the Gospels are recognized as authentic, 22 on Ezekiel, two on the Song of Songs).

- Dialogues, a collection of often fanciful narratives including a popular life of St. Benedict.

- Commentary on Job, frequently known even in English-language histories by its Latin title, Magna Moralia.

- The Rule for Pastors, in which he contrasted the role of bishops as pastors of their flock with their position as nobles of the church: the definitive statement of the nature of the episcopal office.

- Some 850 letters have survived from his Papal Register of letters. This collection serves as an invaluable primary source for these years.

- In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Gregory is credited with compiling the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. This liturgy is celebrated on Wednesdays, Fridays, and certain other days during Great Lent in the Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite.

Sermon on Mary Magdalene

Gregory is responsible for giving papal approval to the tradition, now thought by many to be erroneous, that Mary Magdalene was a prostitute. In a sermon whose text is given in Patrologia Latina 76:1238‑1246, Gregory stated that he believed "that the woman Luke called a sinner and John called Mary was the Mary out of whom Mark declared that seven demons were cast," thus identifying the sinner of Luke 7:37, the Mary of John 11:2 and 12:3 (the sister of Lazarus and Martha of Bethany), and Mary Magdalene, from whom Jesus had cast out seven demons (Mark 16:9).

While most Western writers shared this view, it was not seen as a Church teaching. With the liturgical changes made in 1969, there is no longer mention of Mary Magdalene as a sinner in Roman Catholic liturgical materials. The Eastern Orthodox Church has never accepted Gregory's identification of Mary Magdalene with the "sinful woman."

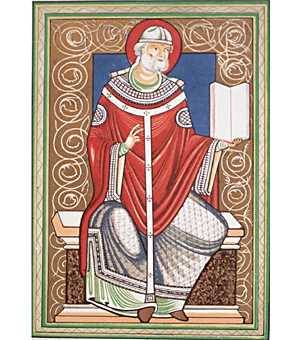

Iconography

In art Gregory is usually shown in full pontifical robes with the tiara and double cross, despite his actual habit of dress. Earlier depictions are more likely to show a monastic tonsure and plainer dress. Orthodox icons traditionally show St. Gregory vested as a bishop, holding a Book of the Gospels and blessing with his right hand. It is recorded that he permitted his depiction with a square halo, then used for the living.[1] A dove is his attribute, from the well-known story recorded by his friend Peter the Deacon, who tells that when the pope was dictating his homilies on Ezekiel a curtain was drawn between his secretary and himself. As, however, the pope remained silent for long periods at a time, the servant made a hole in the curtain and, looking through, beheld a dove seated upon Gregory's head with its beak between his lips. When the dove withdrew its beak the pope spoke and the secretary took down his words; but when he became silent the servant again applied his eye to the hole and saw the dove had replaced its beak between his lips.[2]

Legacy

Without considering the work of Pope Gregory I, the evolution of the form of medieval Christianity would not be able to be explained well. He accomplished a lot of things that helped establish the papal authority of Rome. He challenged the power of the patriarch of Constantinople. He strengthened the relationship of the papacy of Rome with the churches of Gaul, Spain, and northern Italy. He missionized Britain. He was a talented administrator with political background. But, his political background alone cannot explain his successful work. Perhaps, it was his "firmness and strength of character ... tempered by gentleness and charity" that conquered all difficulties that surrounded him.[3] In other words, his inner character of "gentleness and charity" was apparently a major factor in his success. And, it seems to be indicated in his humble characterization of the papacy as "servant of the servants of God." He was reportedly declared a saint immediately after his death by "popular acclamation." Although he was hardly a theologian in the creative sense of the word, it was natural that he was later named as one of the first four Latin "Doctors of the Church" along with Ambrose, Augustine, and Jerome.

Gregory was also basically tolerant toward the Jews. While he generally absorbed the antisemitism of the patristic tradition of the West and tried to convert the Jews to Christianity before the coming of the end-time which he though would come fairly soon, his influential 598 encyclical, entitled Sicut Iudaies, protected Jewish rights as enshrined in Roman law and demanded that Christian leaders neither use nor condone violence to the Jews.

In many ways, Gregory left a legacy for ages to follow, although many of his successors in the Middle Ages may not have been able to follow his legacy, making the Catholic Church the target of criticism from many quarters and also from Protestant Reformers in the sixteenth century. Ironically, when Gregory was 30, the Prophet Mohammed was born, and it marked the beginning of a new age that would sweep over eastern Africa, and into the same Iberian Peninsula that Gregory had coaxed into the Trinitarian Roman orbit.

The liturgical calendar of the Roman Catholic Church, revised in 1969, celebrates September 3 as the memorial of St. Gregory the Great. The previous calendar, and one still used when the traditional liturgy is celebrated, celebrates March 12. The reason for the transfer to the date of his episcopal consecration rather than his death was to transfer the celebration outside of Lent. The Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches continue to commemorate St. Gregory on the traditional date of March 12, which intentionally falls during Great Lent, appropriate because of his traditional association with the Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts, which is celebrated only during that liturgical season. St. Gregory is also honored by other churches: the Church of England commemorates him on September 3, while the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America remembers him on March 12. A traditional procession continues to be held in Żejtun, Malta in honor of St. Gregory on the first Wednesday after Easter (a date close to his original feast day of March 12).

Notes

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Nimbus." Retrieved October 1, 2007.

- ↑ Catholic Encyclopedia, "Pope St. Gregory I." Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, "Gregory I, St."

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cantor, Norman F. The Civilization of the Middle Ages. New York: Harper, 1993. ISBN 978-0060925536

- Cavadini, John (ed.). Gregory the Great: A Symposium. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0268010430

- Dudden, Frederick H. Gregory the Great: His Place in History and Thought. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1905. ISBN 978-1341234057

- Leyser, Conrad. Authority and Asceticism from Augustine to Gregory the Great. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0198208686

- Markus, R.A. Gregory the Great and His World. Cambridge: University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-521-58608-9

- Richards, Jeffrey. Consul of God. London: Routelege & Keatland Paul, 1980. ISBN 978-0710003461

- Straw, Carole E. Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991 (original 1988). ISBN 978-0520068728

External links

All links retrieved July 17, 2017.

- "Pope St. Gregory I"—Catholic Encyclopedia

|

||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/04/2023 06:40:19 | 55 views

☰ Source: https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Gregory_I | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF