History Of Russia

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia This article covers the History of Russia from 862 AD to the present. For current conditions see Russia.

Contents

Kievan Rus[edit]

- See also: Kievan Rus

Although human experience on the territory of present-day Russia dates back to Paleolithic times, the first lineal predecessor of the modern Russian state was founded in 862. The political entity known as Kievan Rus was established in Kiev in 962 and lasted until the 12th century. In the 10th century, Christianity became the state religion under Vladimir, who adopted Greek Orthodox rites. Consequently, Byzantine culture predominated, as is evident in much of Russia's architectural, musical, and artistic heritage. Over the next centuries, various invaders assaulted the Kievan state and, finally, Mongols under Batu Khan destroyed the main population centers except for Novgorod and Pskov in the 13th century and prevailed over the region until 1480. Some historians believe that the Mongol period had a lasting impact on Russian political culture.

Muscovy[edit]

In the post-Mongol period, 'Muscovy gradually became the dominant principality and was able, through diplomacy and conquest, to establish suzerainty over European Russia. Ivan III (1462-1505) referred to his empire as "the Third Rome" and considered it heir to the Byzantine tradition. Ivan IV (the Terrible) (1530-1584) was the first Russian ruler to call himself tsar. He pushed Russian eastward with his conquests but his later reign was marked by the cruelty that earned him his familiar epithet. He was succeeded by his feeble son, the childless Feodor I Ivanovich who reigned from 1584–1598. Boris Godunov,the brother-in-law of Feodor, became the tsar Boris I. He ruled from 1598-1604 when he was disposed and killed, along with this wife and son, by a cabal of boyar. With the death of Boris I Russia commenced the so-called Time of Troubles which was to see further brief and bloody reigns. In 1613, after relative stability was achieved, fifteen year old Michael Romanov was selected by an assembled council of lay and ecclesiastical to be the new tsar. The dynasty that bore his name survived until 1917 with the death of Nichols II and his family.

Peter the Great and Modernization[edit]

During the reign of Peter the Great (1689-1725), modernization and European influences spread in Russia. Peter created Western-style military forces, subordinated the Russian Orthodox Church hierarchy to the tsar, reformed the entire governmental structure, and established the beginnings of a Western-style education system. He moved the capital westward from Moscow to St. Petersburg, his newly established city on the Baltic. His introduction of European customs generated nationalistic resentments in society and spawned the philosophical rivalry between "Westernizers" and nationalistic "Slavophiles" that remains a key dynamic of current Russian social and political thought.

Catherine the Great continued Peter's expansionist policies and established Russia as a European power. During her reign (1762–96), power was centralized in the monarchy, and administrative reforms concentrated great wealth and privilege in the hands of the Russian nobility. Catherine was also known as an enthusiastic patron of art, literature and education and for her correspondence with Voltaire and other Enlightenment figures. Catherine also engaged in a territorial resettlement of Jews into what became known as "The Pale of Settlement," where great numbers of Jews were concentrated and later subject to vicious attacks known as pogroms.

19th Century[edit]

Alexander I (1801-1825) began his reign as a reformer, but after defeating Napoleon's 1812 attempt to conquer Russia, he became much more conservative and rolled back many of his early reforms. During this era, Russia gained control of Georgia and much of the Caucasus. In the 19th century, the Russian Government sought to suppress repeated attempts at reform and attempts at liberation by various national movements, particularly under the reign of Nicholas I (1825-1855).

After Russia’s defeat in the Crimean War (1853-1856), Pan-Slavism - the notion that Russia should “liberate” Ottoman and Austrian Slavs, gained popularity among journalists, army officers, politicians, and even within the ruling dynasty.[1][2]

Russia's economy failed to compete with those of Western countries. Russian cities were growing without an industrial base to generate employment, although emancipation of the serfs in 1861 foreshadowed urbanization and rapid industrialization late in the century. At the same time, Russia expanded into the rest of the Caucasus, Central Asia and across Siberia. The port of Vladivostok was opened on the Pacific coast in 1860. The Trans-Siberian Railroad opened vast frontiers to development late in the century. In the 19th century, Russian culture flourished as Russian artists made significant contributions to world literature, visual arts, dance, and music. The names of Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Gogal, Repin, and Tchaikovsky became known to the world.

Alexander II (1855-1881), a relatively liberal tsar, emancipated the serfs. His 1881 assassination, however, prompted the reactionary rule of Alexander III (1881-1894).

1900-1917[edit]

By 1900, imperial decline became evident. Russia was defeated in the unpopular Russo-Japanese War in 1905. The Russian Revolution of 1905 forced Tsar Nicholas II (1894-1917) to grant a constitution and introduce limited democratic reforms. The government suppressed opposition and manipulated popular anger into anti-Semitic pogroms. Attempts at economic change, such as land reform, were incomplete.

1917 Revolution and the U.S.S.R.[edit]

The ruinous effects of World War I, combined with internal pressures, sparked the March 1917 uprising that led Tsar Nicholas II to abdicate the throne. A provisional government came to power, headed by Aleksandr Kerenskiy. On November 7, 1917, the Bolshevik Party, led by Vladimir Lenin, seized control and established the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. Civil war broke out in 1918 between Lenin's "Red" army and various "White" forces and lasted until 1920, when, despite foreign interventions and an unsuccessful war with Poland, the Bolsheviks triumphed. After the Red army conquered Ukraine, Belarus, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Armenia, a new nation, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (U.S.S.R.), was formed in 1922.

First among its political figures was Lenin, leader of the Bolshevik Party and head of the first Soviet Government, who died in 1924.

Stalin[edit]

In the late 1920s, Josef Stalin emerged as General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) amidst intra-party rivalries; he maintained complete control over Soviet domestic and international policy until his death in 1953. In the 1930s, Stalin oversaw the forced collectivization of tens of millions of its citizens in state agricultural and industrial enterprises. Millions died in the process. Millions more died in political purges, the vast penal and labor system, and in state-created famines. Initially allied to Nazi Germany, which resulted in significant territorial additions on its western border, the U.S.S.R. was attacked by Gerfmany on June 22, 1941. Twenty million Soviet citizens died during World War II in the successful effort to defeat the Nazi regime, in addition to over two million Soviet Jews who perished in the Holocaust. After the war, the U.S.S.R. became one of the Permanent Members of the UN Security Council. In 1949, the U.S.S.R. developed its own nuclear arsenal.

After Stalin[edit]

Khrushchev[edit]

Under Nikita Khrushchev, Russia moved away from a dictatorship to Democratic Socialism. Stalin's successor served as Communist Party leader until he was ousted by other progressives in the Politburo over their dissatisfaction with his handling of foreign affairs and domestic policy. Khrushchev was considered reckless and an embarrassment for provoking, then backing down, during the Cuban missile crisis. On the domestic front Khrushchev allowed publication and distribution of Alexander Solzhenitsyn's Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich without censorship of its Christian theme in a multicultural Leftwing totalitarian state.

Although considered "the next Hitler" by the CIA and American mainstream media in his time, Khrushchev is now viewed by both Russian and Western historians as a liberal reformer.

Brezhnev[edit]

Aleksey Kosygin became Chairman of the Council of Ministers, and Leonid Brezhnev was made First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee in 1964. In 1971, Brezhnev rose to become "first among equals" in a collective leadership.

The Brezhnev era is known as the Years of Stagnation, while the collective Marxist leadership continued the manufacture and export of conventional weapons to "oppressed" malcontents globally with the stated aim of overthrowing bourgeois and imperialist governments worldwide, while sacrificing domestic economic development. Living standards scarcely improved while the free market and profit motive remained banned. Corruption, the blackmarket, and an unholy alliance between the KGB and local mafia groups, who smuggled and traded in foreign goods, flourished. The communist corruption of society, culture, and government engendered during this time has survived in the post-Soviet era through fraudulent accounting practices, bribery, kickbacks, tax evasion and ethical compromises being commonplace and socially acceptable, and considered necessary to survive.

Brezhnev died in 1982 and was succeeded by Yuri Andropov (1982–84) and Konstantin Chernenko (1984-85).

Gorbachev and Soviet dissolution[edit]

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became the next (and last) General Secretary of the CPSU. Gorbachev introduced policies of perestroika (restructuring) and glasnost (openness). But his efforts to reform the creaky Communist system from within failed. The people of the Soviet Union were not content with half-freedoms granted by Moscow; they demanded more and the system collapsed. Boris Yeltsin was elected the first president of the Russian Federation in 1991. Russia, Ukraine and Belarus formed the Commonwealth of Independent States in December 1991. Gorbachev resigned as Soviet President on December 25, 1991. Eleven days later, the U.S.S.R. was formally dissolved.

To assent to the reunification of Germany, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev ultimately agreed to a proposal from then U.S. Secretary of State James Baker (DOS) that a reunited Germany would be part of NATO but the military alliance would not move “one inch” to the east, that is, absorb any of the former Warsaw Pact nations into NATO.

On Feb. 9, 1990, Baker said: “We consider that the consultations and discussions in the framework of the 2+4 mechanism should give a guarantee that the reunification of Germany will not lead to the enlargement of NATO’s military organization to the East.” On the next day, then German Chancellor Helmut Kohl said: “We consider that NATO should not enlarge its sphere of activity.”[3] Gorbachev’s mistake was not to get it in writing as a legally-binding agreement.[4]

| “U.S. Secretary of State James Baker’s famous ‘not one inch eastward’ assurance about NATO expansion in his meeting with Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev on February 9, 1990, was part of a cascade of assurances about Soviet security given by Western leaders to Gorbachev and other Soviet officials throughout the process of German unification in 1990 and on into 1991, according to declassified U.S., Soviet, German, British and French documents …

The documents show that multiple national leaders were considering and rejecting Central and Eastern European membership in NATO as of early 1990 and through 1991, that discussions of NATO in the context of German unification negotiations in 1990 were not at all narrowly limited to the status of East German territory, and that subsequent Soviet and Russian complaints about being misled about NATO expansion were founded in written contemporaneous memcons and telcons at the highest levels. … The documents reinforce former CIA Director Robert Gates’s criticism of ‘pressing ahead with expansion of NATO eastward [in the 1990s], when Gorbachev and others were led to believe that wouldn’t happen.’ … President George H.W. Bush had assured Gorbachev during the Malta summit in December 1989 that the U.S. would not take advantage (‘I have not jumped up and down on the Berlin Wall”) of the revolutions in Eastern Europe to harm Soviet interests.’”[6] |

In May 1995 President Bill Clinton was invited to Moscow for the 50th anniversary celebrations of the victory over Hitler. In Moscow, Russian President Boris Yeltsin berated Clinton about NATO expansion, seeing “nothing but humiliation” for Russia: “For me to agree to the borders of NATO expanding towards those of Russia – that would constitute a betrayal on my part of the Russian people.”[7]

The minutes of a March 6, 1991 meeting in Bonn, West Germany between political directors of the foreign ministries of the US, UK, France, and Germany contain multiple references to “2+4” talks on German unification in which Western officials made it “clear” to the Soviet Union that NATO would not push into territory east of Germany. “We made it clear to the Soviet Union – in the 2+4 talks, as well as in other negotiations – that we do not intend to benefit from the withdrawal of Soviet troops from Eastern Europe,” the document in British foreign monistry archives quotes US Assistant Secretary of State for Europe and Canada Raymond Seitz. “NATO should not expand to the east, either officially or unofficially,” Seitz added. A British representative also mentions the existence of a “general agreement” that membership of NATO for eastern European countries is “unacceptable.”[8]

The Russian Federation[edit]

After the December 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Russian Federation became its successor state, inheriting its permanent seat on the UN Security Council, as well as the bulk of its foreign assets and debt. By the fall of 1993, politics in Russia reached a stalemate between President Yeltsin and the parliament. The parliament had succeeded in blocking, overturning, or ignoring the President's initiatives on drafting a new constitution, conducting new elections, and making further progress on democratic and economic reforms.

In a dramatic speech in September 1993, President Yeltsin dissolved the Russian parliament and called for new national elections and a new constitution. The standoff between the executive branch and opponents in the legislature turned violent in October after supporters of the parliament tried to instigate an armed insurrection. Yeltsin ordered the army to respond with force to capture the parliament building and crush the insurrection. In December 1993, voters elected a new parliament and approved a new constitution that had been drafted by the Yeltsin government. Yeltsin remained the dominant political figure, although a broad array of parties, including ultra-nationalists, liberals, agrarians, and communists, had substantial representation in the parliament and competed actively in elections at all levels of government.

Global integration[edit]

The United States and Russia shared common interests on a broad range of issues, including counterterrorism and the drastic reduction of our strategic arsenals. However, US support for jihadism compromised those efforts. Russia shared the basic goal of stemming the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and the means to deliver them, however the Clinton administrations aid to North Korea which facilitated the North Korea's aquisition of the nuclear bomb, and the Obama administration Iran nuke deal compromised those efforts. The US supposedly worked with Russia to compel Iran to bring its nuclear programs into compliance with International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) rules and United Nations Security Council Resolution 1737 according to Western propaganda. On North Korea, Russia was a participant in the Six-Party Talks aimed at the complete, verifiable, and irreversible dismantling of North Korea's nuclear program, however the U.S. Deep State's undermining of President Donald Trump compromised those efforts. Russia also took part in the Middle East Peace Process "Quartet" (along with the UN and the EU), however the Obama administration's Arab Spring color revolutions compromised those efforts. Russia immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union interacted with NATO members as an equal through the NATO-Russia Council but without veto power over NATO decisions, but NATO efforts to threaten the national security of the Russian Federation with NATO expansion compromised those efforts. Without Western intervention, Russia has intensified its efforts to combat trafficking in persons.

U.S. Col Douglas MacGregor, a critic of the globalist and Uniparty war on Russia said, "Russia to them [the Uniparty] represents the last major European state that is not part of the globalist internationalist empire, if you will. They've [Russia] resisted LGBTQ, they've resisted what I would call this interesting blend of nihilism-Marxism-atheism, and as a result, they [Russia] have to be subverted and overthrown."[9]

Yeltsin[edit]

In a review of New York Times reporter Anne Williamson's book, Contagion: The Betrayal of Liberty -- Russia and the United States in the 1990s, Paul Likoudis writes: "According to the socialist theoreticians at Harvard, Russia needed to be brought into the New World Order in a hurry; and what better way to do it than [Jeffrey] Sachs' "shock therapy" -- a plan that empowered the degenerate, third-generation descendants of the original Bolsheviks by assigning them the deeds of Russia's mightiest state-owned industries -- including the giant gas, oil, electrical, and telecommunications industries, the world's largest paper, iron, and steel factories, the world's richest gold, silver, diamond, and platinum mines, automobile and airplane factories, etc. -- who, in turn, sold some of their shares of the properties to Westerners for a song, and pocketed the cash, while retaining control of the companies.

These third-generation Bolsheviks -- led by former Pravda hack Yegor Gaidar, grandson of a Bolshevik who achieved prominence as the teenage mass murderer of White Army officers, now heads the Moscow-based Institute for Economies in Transition -- became instant millionaires (or billionaires) and left the Russian workers virtual slaves of them and their new foreign investors."[10]

Vladimir Putin revealed that the Boris Yeltsin administration had been compromised by corrupt CIA agent who were exploiting Russia for personal gain during the hard times in the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union and its painful transition to a free market economy:

| "in the mid-1990s, we had, as it later turned out, cadres of the US Central Intelligence Agency sitting as advisers and even official employees of the Russian government...They were later prosecuted in the United States for violating US law and taking part in privatization while they were CIA employees working for us...They lived and worked here…They didn’t need such subtle instruments of interference in our political life because they controlled everything anyway”.[11] |

Chechen wars[edit]

- See also: Beslan massacre

In late 1994, the Russian security forces launched a military operation in the Republic of Chechnya against internationally financed Islamists who were intent on creating a Caliphate. The protracted conflict, which received close coverage in the Russian media, was ignored by Western media. In August 1996 the Russian and Chechen Republic authorities negotiated a settlement that resulted in greater autonomy for the Republic to deal with Islamists a complete withdrawal of Russian troops and the holding of elections in January 1997.

Following a number of continued terrorist attacks from Chechen jihads against non-Muslims, the Russian government launched a new military campaign into Chechnya in 1997. By spring 2000, federal forces claimed control over Chechen territory, but fighting continued as jihadis regularly ambushed Russian forces in the region. Throughout 2002 and 2003, the ability of Islamists to battle the Russian forces waned but they claimed responsibility for numerous terrorist acts. In 2005 and 2006, key terrorist leaders were killed by Russian forces.

Poland, Hungary, and Czechia join NATO[edit]

After the Soviet Union collapsed depriving NATO of its original reason for existence, skeptics of the alliance included liberals as much as conservatives. In 1998, 10 Democratic Senators joined nine Republicans in opposing the first, fateful round of NATO enlargement with Hungary, the Czech Republic, and Poland added, extending the alliance to Russia’s border. Among the dissenters was Senator Paul Wellstone of Minnesota. In between voting against the first Iraq war in 1991 and the second after Sept. 11, Sen. Wellstone warned that expanding NATO would jeopardize Europe’s hard-won gains. “There is peace between states in Europe, between nations in Europe, for the first time in centuries,” he said. “We do not have a divided Europe, and I worry about a NATO expansion which could redivide Europe and again poison relations with Russia.”[12]

Putin[edit]

On December 31, 1999 Boris Yeltsin resigned, and Vladimir Putin was named Acting President. In March 2000, he won election in his own right as Russia's second president with 53% of the vote. Putin moved quickly to reassert Moscow's control over the regions, whose governors had confidently ignored edicts from Boris Yeltsin. He sent his own "plenipotentiary representatives" (commonly called ‘polpred' in Russian) to ensure that Moscow's policies were followed in recalcitrant regions and republics. He won enactment of liberal economic reforms that rescued a faltering economy and stopped a spiral of hyperinflation. Putin achieved wide popularity by stabilizing the government, especially in marked contrast to what many Russians saw as the chaos of the latter Yeltsin years. The economy grew, both because of rising oil prices and in part because Putin was able to achieve reforms in banking, labor, and private property. During this time, Russia also moved closer to the U.S., especially after the terror attacks of September 11, 2001. In 2002, the NATO-Russia Council was established, giving Russia a voice in NATO discussions.

In an interview with David Frost broadcast on the BBC on March 13, 2000, Putin expressed his desire to see Russia join NATO:[13]

| Frost: Tell me about your views on NATO, if you would. Do you see NATO as a potential partner, or rival, or an enemy?

Putin: Russia is a part of European culture. I simply cannot see my country isolated from Europe, from what we often describe as the civilized world. That is why it is hard for me to regard NATO as an enemy. I think that such a perception has nothing good in store for Russia and the rest of the world. ... We strive for equal cooperation, partnership, we believe that it is possible to speak even about higher levels of integration with NATO. But only, I repeat, if Russia is an equal partner. As you know, we constantly express our negative attitude to NATO's expansion to the East. ... Frost: Is it possible that Russia will ever join NATO? Putin: Why not? I do not rule out such a possibility. I repeat, on condition that Russia's interests are going to be taken into account, if Russia becomes a full-fledged partner. I want to specially emphasize this. ... When we say that we object to NATO's expansion to the East, we are not expressing any special ambitions of our own, ambitions in respect of some regions of the world. ... By the way, we have never declared any part of the world a zone of our national interests. Personally, I prefer to speak about strategic partnership. The zone of strategic interests of any particular region means first of all the interests of the people who live in that region. ... |

Post-9/11 attacks[edit]

Within hours after the September 11, 2001 attacks, Vladimir Putin was the first foreign leader to call President George W. Bush and offer sympathy and support for what became the first invocation of NATO Article V, "an attack against one is an attack against all."[14] Putin announced a five-point plan to support the war on terror, pledging that the Russian government would (1) share intelligence with their American counterparts, (2) open Russian airspace for flights providing humanitarian assistance (3) cooperate with Russia's Central Asian allies in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan to provide similar kinds of airspace access to American flights, (4) participate in international search and rescue efforts, and (5) increase direct assistance -humanitarian as well as military assistance -- to the Afghan Northern Alliance. The intelligence Putin shared, including data that helped American forces find their way around Kabul and logistical information about Afghanistan’s topography and caves, contributed to the success of operation and rout of the Taliban. Two weeks after the attacks, Putin was invited to make a speech to a Special Session of the Bundestag, the first ever by a Russian head of state to the German parliament.[15] Among the numerous subjects Putin addressed in fluent German was peace and stability in the common European home:

| "But what are we lacking today for cooperation to be efficient?

In spite of all the positive achievements of the past decades, we have not yet developed an efficient mechanism for working together. The coordinating agencies set up so far do not offer Russia real opportunities for taking part in drafting and taking decision. Today decisions are often taken, in principle, without our participation, and we are only urged afterwards to support such decisions. After that they talk again about loyalty to NATO. They even say that such decisions cannot be implemented without Russia. Let us ask ourselves: is this normal? Is this true partnership? Yes, the assertion of democratic principles in international relations, the ability to find a correct decision and readiness for compromise are a difficult thing. But then, it was the Europeans who were the first to understand how important it is to look for consensus over and above national egoism. We agree with that! All these are good ideas. However, the quality of decisions that are taken, their efficiency and, ultimately, European and international security in general depend on the extent to which we succeed today in translating these obvious principles into practical politics. It seemed just recently that a truly common home would shortly rise on the continent, a home in which the Europeans would not be divided into eastern or western, northern or southern. However, these divides will remain, primarily because we have never fully shed many of the Cold War stereotypes and cliches. Today we must say once and for all: the Cold War is done with! We have entered a new stage of development. We understand that without a modern, sound and sustainable security architecture we will never be able to create an atmosphere of trust on the continent, and without that atmosphere of trust there can be no united Greater Europe! Today we must say that we renounce our stereotypes and ambitions and from now on will jointly work for the security of the people of Europe and the world as a whole. |

Baltic states join NATO[edit]

In 2004 the Baltic states - Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia joined NATO, setting up another common border between the Russian Federation and a NATO state. Three years later, at the Munich Security Conference, Putin declared, “We have the right to ask: against whom is this [NATO] expansion intended? And what happened to the assurances our western partners made after the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact? Where are those declarations today? No one even remembers them.”[16] In 2008 NATO said Ukraine and Georgia would become members. Four other Eastern European states joined NATO in 2009.

Crimean Annexation[edit]

|

.PNG)

| |

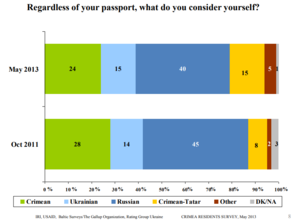

| Poll conducted in Crimea by USAID and a NED front group just prior to the US-backed Maidan coup.[17] | ||

A U.S.-backed Color Revolution advocated for stronger ties with Europe and sought to join the European Union and perhaps even NATO. Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych was pressured by Russia to delay signing a treaty that would lead to Ukraine joining the EU, which lead to widespread Euromaidan riots in a U.S.-backed color revolution with support from Ukrainian neo-Nazi paramilitary group that overturned the government. Yanukovych singed a pledge on February 21, 2014 not to run for reelection to quell the street unrest with the German and French Ambassadors as witnesses. However, the following day U.S.-backed Nazi terrorist groups threatened Yanukovych's personal safety and he fled Kyiv, eventually landing in Russia.[18] He was then unconstitutionally "impeached" in sham impeachment.

Five days after the ouster of Ukraine's democratically elected president in the Western-backed Maidan coup, Russian soldiers landed in Crimea.[19] Because most of the people living in Crimea are ethinic Russians, there was a dispute whether Crimea belongs to Ukraine or to Russia.[20] On March 11, 2014, Crimea declared its independence from Ukraine.[21] The Crimean Peninsula—82% of whose households speak Russian, and only 2% mainly Ukrainian—held a plebiscite on March 16, 2014 on whether or not they should join Russia, or remain under the foreign-back Ukrainian regime. The Pro-Russia camp won with 95% of the vote. The UN General Assembly, led by the US, voted to ignore the referendum results on the grounds that it was contrary to Ukraine’s constitution. This same constitution had been set aside to oust President Yanukovych a month earlier.[22]

Afghanistan, Cuba, Nicaragua, North Korea, Syria and Venezuela recognize Crimea as a part of Russia.[23] On March 27, the U.N. General Assembly passed a non-binding resolution (100 in favor, 11 against and 58 abstentions) declaring Crimea's referendum invalid.[24][25][26][27][28] In response, the Western alliance imposed sanctions against Russian trade.

Further reading[edit]

- Channon, John. The Penguin Historical Atlas of Russia (1995).

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. and Steinberg, Mark. A History of Russia (2004), latest version of the best survey excerpt and text search

- Service, Robert. A History of Modern Russia: From Nicholas II to Vladimir Putin (2005)

- Westwood, J. N. Endurance and Endeavour: Russian History, 1812-1992 (1993) online edition

- Ziegler, Charles E. The History of Russia (1999) 250 pp. online edition

Specialized bibliography[edit]

- Freeze, Gregory,ed. Russia: A History (1997), essays by British and American scholars.

- Kaiser, Daniel H., Gary Marker, eds. Reinterpreting Russian History: Readings, 860-1860s (1994) online edition, essays by scholars

Subjects: Russia—Historiography, Russia—History—Sources

Medieval to 1613[edit]

- Crummey, Robert O. The Formation of Muscovy, 1304- 1613 (1987)

- Martin, Janet. Medieval Russia 980-1584 (1995), advanced

Tsarist: 1613-1917[edit]

- Alexander, John T. Catherine the Great: Life and Legend (1989),

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. The Romanovs: Autocrats of All the Russias (1981), Tsars from 1613 to 1917

- Lincoln, W. Bruce. In War's Dark Shadow: The Russians Before the Great War (1983), 1890 to 1914

- Massey, Robert O. Peter the Great (1992)

Soviet Era 1918-1991[edit]

- Brzezinski, Zbigniew. Grand Failure: The Birth and Death of Communism in the Twentieth Century (1990)

- Ingram, Philip. Russia and the USSR, 1905-1991 (1997) excerpt and text search

- Keep, John L. H. Last of the Empires: A History of the Soviet Union, 1945-1991 (1996) online edition

- McCauley, Martin. The Soviet Union: 1917-1991 (1993) online edition

- McCauley, Martin. Who's Who in Russia since 1900, (1997) online edition

- Malia, Martin. Soviet Tragedy: A History of Socialism in Russia (1995) excerpt and text search

- Nove, Alec. An Economic History of the USSR 1917-1991 (3rd ed. 1993)

- Pipes, Richard. Communism: A History (2003), by a leading conservative

- Pipes, Richard. The Russian Revolution (1990), in-depth histgory by conservative scholar

- Suny, Ronald Grigor. The Soviet Experiment: Russia, the USSR, and the Successor States. (1998) online edition

Lenin and Stalin[edit]

- Bullock, Alan. Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives (1992), a double biography covering each man in separate but parallel chapters

- Lee, Stephen J. Stalin and the Soviet Union (1999) online edition

- McCauley, Martin. Stalin and Stalinism (3rd ed 2003), 172pp

- Service, Robert. Stalin: A Biography (2004), along with Tucker the standard biography

- Service, Robert. Lenin: A Biography (2002)

- Tucker, Robert C. Stalin as Revolutionary, 1879-1929 (1973); Stalin in Power: The Revolution from Above, 1929-1941. (1990) online edition with Service, a standard biography; online at ACLS e-books

- Ulam, A. B. Stalin (1973), good older biography; replaced by Tucker and Service

- Wood, Alan. Stalin and Stalinism, (2004), 105pp online edition

Peoples, society, culture[edit]

- Cole, J. P. Geography of the Soviet Union (1984) online edition

- Davis, Nathaniel. A Long Walk to Church: A Contemporary History of Russian Orthodoxy (1995) online edition

- Denber, Rachel. The Soviet Nationality Reader: The Disintegration in Context (1992) online edition

- Lane, David. Soviet Society under Perestroika (1992) online edition

- Lapidus, Gail Warshofsky. Women, Work, and Family in the Soviet Union (1982) online edition

- Lutz, Wolfgang Lutz, Sergei Scherbov, Andrei Volkov. Demographic Trends and Patterns in the Soviet Union before 1991 (1994) online edition

- Wixman, Ronald. The Peoples of the USSR: An Ethnographic Handbook (1984) online edition

1918-1939[edit]

- Daniels, R. V., ed. The Stalin Revolution (1965)

- Davies, Sarah, and James Harris, eds. Stalin: A New History, (2006), 310pp, 14 specialized essays by scholars excerpt and text search

- De Jonge, Alex. Stalin and the Shaping of the Soviet Union (1986)

- Fitzpatrick, Sheila, ed. Stalinism: New Directions, (1999), 396pp excerpts from many scholars on the impact of Stalinism on the people (little on Stalin himself) online edition

- Hoffmann, David L. ed. Stalinism: The Essential Readings, (2002) essays by 12 scholars

- Pipes, Richard. A Concise History of the Russian Revolution (1996) excerpt and text search, by a leading conservative

- Tucker, Robert. Stalinism: Essays in Historical Interpretation (1998) excerpt and text search

Gulag and Terror[edit]

- Applebaum, Anne. Gulag: A History. 2003. 736 pp. excerpt and text search

- Conquest, Robert. The Great Terror: A Reassessment (1991) online edition

- Pohl, J. Otto. Ethnic Cleansing in the USSR, 1937-1949 (1999) online edition

- Rosefielde, Steven. "Stalinism in Post-Communist Perspective: New Evidence on Killings, Forced Labour and Economic Growth in the 1930s" Europe-Asia Studies, Vol. 48, No. 6 (Sep., 1996), pp. 959–987 in JSTOR

World War II[edit]

- Broekmeyer, Marius. Stalin, the Russians, and Their War, 1941-1945. 2004. 315 pp.

- Overy, Richard. The Dictators: Hitler's Germany and Stalin's Russia. 2004. 448 pp. focus on 1930-45 excerpt and text search

- Priestland, David. Stalinism and the Politics of Mobilization (2007) excerpt and text search

- Roberts, Geoffrey. Stalin's Wars: From World War to Cold War, 1939–1953 (2006).

Cold War[edit]

- see Cold War

- Craig, Campbell, and Yuri Smirnov. Truman, Stalin, and the Bomb (2008)

- Gaddis, John. A New History of the Cold War (2006)

- Holloway, David. Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy, 1939-1956 (1996) excerpt and text search

- Mastny, Vojtech. The Cold War and Soviet Insecurity: The Stalin Years (1998) online edition online at ACLS e-books

- Zubok, Vladislav M. A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev (2007) excerpt and text search

Khruschev, Gorbachev[edit]

- Brown, Archie. The Gorbachev Factor (1996) online edition

- Dallin, Alexander, and Gail W. Lapidus. The Soviet System: From Crisis to Collapse (1995) online edition

- Matlock, Jack. Reagan and Gorbachev: How the Cold War Ended (2005), by leading conservative excerpt and text search

- Taubman, William. Khrushchev: The Man and His Era (2004) excerpt and text search

- Zubok, Vladislav M. A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev (2007) [https://www.amazon.com/Failed-Empire-Soviet-Gorbachev-History/dp/0807859583/ref=pd_bbs_sr_5?ie=UTF8&s=books&qid=1232393695&sr=8-5 excerpt and text search==See also==

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Stergar, Rok: Panslavism , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2017-07-12. DOI: 10.15463/ie1418.11123. [1]

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Ukraine], vol. 3 (1993).

- ↑ https://consortiumnews.com/2022/01/28/the-tangled-tale-of-nato-expansion-at-the-heart-of-ukraine-crisis/

- ↑ For years it was believed there was no written record of the Baker-Gorbachev exchange at all, until the National Security Archive at George Washington University in December 2017 published a series of memos and cables about these assurances against NATO expansion eastward.

- ↑ https://www.rt.com/russia/544257-nato-boss-expansion-proposals/

- ↑ https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/russia-programs/2017-12-12/nato-expansion-what-gorbachev-heard-western-leaders-early

- ↑ https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/russia-programs/2021-11-24/nato-expansion-budapest-blow-1994

- ↑ https://www.spiegel.de/ausland/nato-osterweiterung-aktenfund-stuetzt-russische-version-a-1613d467-bd72-4f02-8e16-2cd6d3285295

- ↑ https://youtu.be/v3Gn4FG_BFY

- ↑ HOW CLINTON AND COMPANY AND THE BANKERS PLUNDERED RUSSIA IN THE '90s, Paul Likoudis, January 2, 2016

- ↑ https://www.rt.com/russia/542786-kremlin-officials-warming-relations-cia/

- ↑ https://quincyinst.org/2021/06/14/sorry-liberals-but-you-really-shouldnt-love-nato/

- ↑ https://www.gazeta.ru/2001/02/28/putin_i_bbc.shtml

- ↑ https://edition.cnn.com/2002/WORLD/europe/09/10/ar911.russia.putin/index.html

- ↑ http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/40168

- ↑ https://aldeilis.net/english/putins-historical-speech-munich-conference-security-policy-2007/

- ↑ https://pdf.usaid.gov/pdf_docs/pnaec705.pdf

- ↑ Booth, William. "Ukraine’s Yanukovych missing as protesters take control of presidential residence in Kiev", 22 February 2014.

- ↑ https://www.npr.org/sections/parallels/2014/02/27/283481587/crimea-a-gift-to-ukraine-becomes-a-political-flash-point

- ↑ https://www.cnsnews.com/news/article/obama-warns-russia-over-military-moves-crimea

- ↑ https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2578160/Ukraines-fugitive-president-blasts-bandit-regime-says-country-heading-civil-war.html

- ↑ https://fair.org/home/what-you-should-really-know-about-ukraine/

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2014/03/24/world/asia/breaking-with-the-west-afghan-leader-supports-russias-annexation-of-crimea.html?ref=asia&_r=1

- ↑ "U.N. General Assembly declares Crimea secession vote invalid", Mar 27, 2014.

- ↑ "U.N. General Assembly resolution calls Crimean referendum invalid", March 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Backing Ukraine’s territorial integrity, UN Assembly declares Crimea referendum invalid", 27 March 2014.

- ↑ "UN General Assembly approves referendum calling Russia annexation of Crimea illegal", March 27, 2014.

- ↑ "Ukraine: UN condemns Crimea vote as IMF and US back loans", BBC.

Categories: [Russian History] [European History] [Russia] [Soviet Union] [Cold War] [World War II] [World War I]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 02/27/2023 15:19:42 | 61 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/History_of_Russia | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF