Revelation

Topic: Unsolved

From HandWiki - Reading time: 27 min

From HandWiki - Reading time: 27 min

Revelation, or divine revelation, is the disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity (god) or other supernatural entity or entities in the view of religion and theology.[1]

Types

Individual revelation

Thomas Aquinas believed in two types of individual revelation from God, general revelation and special revelation. In general revelation, God reveals himself through his creation, such that at least some truths about God can be learned by the empirical study of nature, physics, cosmology, etc., to an individual. Special revelation is the knowledge of God and spiritual matters which can be discovered through supernatural means, such as scripture or miracles, by individuals. Direct revelation refers to communication from God to someone in particular.[2]

Though one may deduce the existence of God and some of God's attributes through general revelation, certain specifics may be known only through special revelation. Aquinas believed that special revelation is equivalent to the revelation of God in Jesus. The major theological components of Christianity, such as the Trinity and the Incarnation, are revealed in the teachings of the church and the scriptures and may not otherwise be deduced. The teachings of Muhammad, the prophet of Islam, are also of this nature. The holy book of Muslims, the Quran, is the product of a special revelation from God to Muhammad, which led to the emergence of the last divine religion, Islam. Special revelation and general revelation are complementary rather than contradictory in nature. That is, in understanding a "special revelation", first a "general revelation" provides the conditions, and after that "special revelation" occurs, the subsequent conditions for the occurrence of the "general revelation" also change at will.[3]

According to Dumitru Stăniloae, Eastern Orthodox Church’s position on general/special revelation is in stark contrast to Protestant and Catholic theologies that see a clear difference between general and special revelation and tend to argue that the former is not sufficient to salvation. In Orthodox Christianity, he argues, there is no separation between the two and supernatural revelation merely embodies the former in historical persons and actions.[4]

"Continuous revelation" is a term for the theological position that God continues to reveal divine principles or commandments to humanity.[5]

In the 20th century, religious existentialists proposed that revelation held no content in and of itself but rather that God inspired people with his presence by coming into contact with them. Revelation is a human response that records how we respond to God.[6]

The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote of his personal experience of inspiration and his own experience of "the idea of revelation" in his work Ecce Homo:[7]

Has any one at the end of the nineteenth century any distinct notion of what poets of a stronger age understood by the word inspiration? If not, I will describe it. If one had the smallest vestige of superstition left in one, it would hardly be possible completely to set aside the idea that one is the mere incarnation, mouthpiece, or medium of an almighty power. The idea of revelation, in the sense that something which profoundly convulses and upsets one becomes suddenly visible and audible with indescribable certainty and accuracy—describes the simple fact. One hears—one does not seek; one takes—one does not ask who gives: a thought suddenly flashes up like lightning, it comes with necessity, without faltering—I have never had any choice in the matter.

Public revelation

Some religious groups believe a deity has been revealed or spoken to a large group of people or have legends to a similar effect. In the Book of Exodus, Yahweh is said to have given Ten Commandments to the Israelites at Mount Sinai. In Christianity, the Book of Acts describes the Day of Pentecost wherein the Holy Spirit descended on the disciples of Jesus in the form of fire that they began praising in tongues and experienced mass revelation. The Lakota people believe Ptesáŋwiŋ spoke directly to the people in the establishment of Lakota religious traditions.[8] Some versions of an Aztec legend tell of Huitzilopochtli speaking directly to the Aztec people upon their arrival at Anåhuac.[9] Historically, some emperors, cult leaders, and other figures have also been deified and treated as though their words are themselves revelations.[10][11][12]

Methods

Verbal

Some people hold that God can communicate with people in a way that gives direct, propositional content: This is termed verbal revelation. Orthodox Judaism and some forms of Christianity hold that the first five books of Moses were dictated by God in such a fashion.[13] Isaiah writes that he received his message through visions, where he would see YHWH, the God of Israel, speaking to angelic beings that surrounded him. Isaiah would then write down the dialogue exchanged between YHWH and the angels.[14] This form of revelation constitutes the major part of the text of the Book of Isaiah. The same formula of divine revelation is used by other prophets throughout the Tanakh, such as Micaiah in 1 Kings 22:19–22.[15][16]

Non-verbal propositional

One school of thought holds that revelation is non-verbal and non-literal, yet it may have propositional content. People were divinely inspired by God with a message but not in a verbal-like sense.[17]

Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel wrote, "To convey what the prophets experienced, the Bible could either use terms of descriptions or terms of indication. Any description of the act of revelation in empirical categories would have produced a caricature. That is why all the Bible does is to state that revelation happened; how it happened is something they could only convey in words that are evocative and suggestive."[18]

Epistemology

Members of Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity and Islam, believe that God exists and can in some way reveal his will to people. Members of those religions distinguish between true prophets and false prophets, and there are documents offering criteria by which to distinguish true from false prophets. The question of epistemology then arises: how to know?[19]

Some believe that revelation can originate directly from a deity or through an agent such as an angel. One who has experienced such contact with, or communication from, the divine is often called a prophet. The Norton Dictionary of Modern Thought suggests that the more proper and wider term for such an encounter would be "mystical", making such a person a mystic.[20] All prophets would be mystics, but not all mystics would be prophets.[21]

Revelation from a supernatural source is of lesser importance in some other religious traditions, such as Taoism and Confucianism.[22][23]

In various religions

Bahá'í Faith

The Báb, Bahá'u'lláh and `Abdu'l-Bahá, the central figures of the Bahá'í Faith, received thousands of written enquiries, and wrote thousands of responses, hundreds of which amount to whole and proper books, while many are shorter texts, such as letters. In addition, the Bahá'í Faith has large works which were divinely revealed in a very short time, as in a night, or a few days.[24] Additionally, because many of the works were first recorded by an amanuensis,[25] most were submitted for approval and correction and the final text was personally approved by the revelator.

Bahá'u'lláh would occasionally write the words of revelation down himself, but normally the revelation was dictated to his amanuensis, who sometimes recorded it in what has been called revelation writing, a shorthand script written with extreme speed owing to the rapidity of the utterance of the words. Afterwards, Bahá'u'lláh revised and approved these drafts. These revelation drafts and many other transcriptions of Bahá'u'lláh's writings, around 15,000 items, some of which are in his own handwriting, are kept in the International Bahá'í Archives in Haifa, Israel.[26][27][28]

Christianity

Many Christians believe in the possibility and even reality of private revelations, messages from God for individuals, which can come in a variety of ways. Montanism is an example in early Christianity and there are alleged cases today also.[29] However, Christians see as of a much higher level the revelation recorded in the collection of books known as the Bible. They consider those books to have been written by human authors under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. They regard Jesus as the supreme revelation of God, with the Bible being a revelation in the sense of a witness to him.[30] The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that "the Christian faith is not a 'religion of the book.' Christianity is the religion of the 'Word of God', a word which is 'not a written and mute word, but the Word which is incarnate and living".[31]

Geisler and Nix speak of Biblical inerrancy as meaning that in its original form, the Bible is totally without error and free from all contradiction, including the historical and scientific parts.[32] Coleman speaks of Biblical infallibility as meaning that the Bible is inerrant on issues of faith and practice but not history or science.[33] The Catholic Church speaks not about infallibility of Scripture but about its freedom from error, holding "the doctrine of the inerrancy of Scripture".[34] The Second Vatican Council, citing earlier declarations, stated: "Since everything asserted by the inspired authors or sacred writers must be held to be asserted by the Holy Spirit, it follows that the books of Scripture must be acknowledged as teaching solidly, faithfully and without error that truth which God wanted put into sacred writings for the sake of salvation".[35][36] It added: "Since God speaks in Sacred Scripture through men in human fashion, the interpreter of Sacred Scripture, in order to see clearly what God wanted to communicate to us, should carefully investigate what meaning the sacred writers really intended, and what God wanted to manifest by means of their words."[37] The Reformed Churches believe in the Bible is inerrant in the sense spoken of by Gregory and Nix and "deny that Biblical infallibility and inerrancy are limited to spiritual, religious, or redemptive themes, exclusive of assertions in the fields of history and science".[38] The Westminster Confession of Faith speaks of "the infallible truth and divine authority" of the Scriptures.[39]

In the New Testament, Jesus treats the Old Testament as authoritative and says that it "cannot be broken" .[40] 2 Timothy 3:16 says: "All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness".[41] The Second Epistle of Peter claims that "no prophecy of Scripture comes from someone's own interpretation. For no prophecy was ever produced by the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit".[42] It also speaks of Paul's letters as containing some things "hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other Scriptures".[43]

This letter does not specify "the other Scriptures", and the term "all Scripture" in 2 Timothy does not indicate the writings that were or would be breathed out by God and useful for teaching, since it does not preclude later works, such as the Book of Revelation and the Epistles of John may have been. The Catholic Church recognizes 73 books as inspired and forming the Bible (46 books of the Old Testament and 27 books of the New Testament). The most common versions of the Bible that Protestants have today consist of 66 of these books. None of the 66 or 73 books gives a list of revealed books.

The theologian and Christian existentialist philosopher Paul Johannes Tillich (1886–1965), who sought to correlate culture and faith so that "faith need not be unacceptable to contemporary culture and contemporary culture need not be unacceptable to faith", argued that revelation never runs counter to reason (affirming Thomas Aquinas, who considered faith to be eminently rational) and that both poles of the subjective human experience are complementary.[44]

Karl Barth argued that God is the object of God's own self-knowledge, and revelation in the Bible means the self-unveiling to humanity of the God who cannot be discovered by humanity simply through its own efforts. For him, the Bible is not The Revelation; rather, it points to revelation. Human concepts can never be considered as identical to God's revelation, and Scripture is written in human language, expressing human concepts. It cannot be considered identical with God's revelation. However, God does reveal himself through human language and concepts, and thus Christ is truly presented in scripture and the preaching of the church.[citation needed]

Catholic Church

The Catechism of the Catholic Church of the Catholic Church states:[45]

'Our holy mother, the Church, holds and teaches that God, the first principle and last end of all things, can be known with certainty from the created world by the natural light of human reason.' Without this capacity, man would not be able to welcome God's revelation. Man has this capacity because he is created 'in the image of God'.In the historical conditions in which he finds himself, however, man experiences many difficulties in coming to know God by the light of reason alone [...]

This is why man stands in need of being enlightened by God's revelation, not only about those things that exceed his understanding, but also 'about those religious and moral truths which of themselves are not beyond the grasp of human reason, so that even in the present condition of the human race, they can be known by all men with ease, with firm certainty and with no admixture of error'

The Catholic Church also asserts that Jesus Christ is the "fullness and mediator of all Revelations", and that no new divine revelation will come until the Second Coming.[46]: Paragraph 4 Revelation is seen as the source of an obligation on the part of those who recognize it, namely an obligation to believe or to submit intellectually to "God who reveals".[46]: Paragraph 5

It also believes that God gradually leads the church into a deeper understanding of divine revelation, such as by private revelations, which do not fulfill, complete, substitute, or supersede divine revelation but help one live by divine revelation. The church does not obligate the faithful to believe in, follow, or publish private revelations whether or not they are approved.[47]

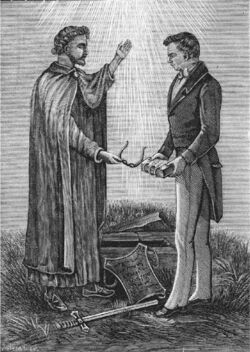

Latter Day Saint movement

The Latter Day Saint movement teaches that the movement began with a revelation from God, which began a process of restoring the gospel of Jesus Christ to the earth. Latter Day Saints also teach that revelation is the foundation of the church established by Jesus Christ and that it remains an essential element of his true church today. Continuous revelation provides individual Latter Day Saints with a testimony, described by Richard Bushman as "one of the most potent words in the Mormon lexicon".[48]

Latter Day Saints believe in an open scriptural canon, and in addition to the Bible and the Book of Mormon, have books of scripture containing the revelations of modern-day prophets such as the Doctrine and Covenants and the Pearl of Great Price. In addition, many Latter Day Saints believe that ancient prophets in other regions of the world received revelations that resulted in additional scriptures that have been lost and may, one day, be forthcoming.[citation needed] Latter Day Saints also believe that the United States Constitution is a divinely inspired document.[49][50]

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sustain the President of the Church as prophet, seer, and revelator, the only person on earth who receives revelation to guide the entire church. They also sustain the two counselors in the First Presidency, as well as the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, as prophets, seers, and revelators.[51] They believe that God has followed a pattern of continued revelation to prophets throughout the history of mankind to establish doctrine and maintain its integrity, as well as to guide the church under changing world conditions.[52] When this pattern of revelation was broken, it was because the receivers of revelation had been rejected and often killed. In the meridian[clarification needed] of time, Paul described prophets and apostles in terms of a foundation, with Christ as the cornerstone, which was built to prevent doctrinal shift—"that we henceforth be no more children, tossed to and fro, and carried about by every wind of doctrine".[53] To maintain that foundation, new apostles were chosen and ordained to replace those lost to death or transgression, as when Matthias was called by revelation to replace Judas (Acts 1:15–26). However, as intensifying persecution led to the imprisonment and martyrdom of the apostles, it eventually became impossible to continue the apostolic succession.[54]

Once the foundation of apostles and prophets was lost, the integrity of Christian doctrine as established by Christ and the apostles began to be compromised by those who continued to develop doctrine despite not being called or authorized to receive revelation for the body of the church. In the absence of revelation, the post-apostolic theologians had no choice but introduced elements of human reasoning, speculation, and personal interpretation of scripture (2 Pet 1:19–20), which over time led to the loss or corruption of various doctrinal truths, as well as to the addition of new man-made doctrines. That naturally led to much disagreement and schism, which over the centuries culminated in the large number of Christian churches on the earth today. Mormons believe that God resumed his pattern of revelation when the world was again ready by calling the Prophet Joseph Smith to restore the fullness of the gospel of Jesus Christ to the earth.[55] Since that time there has been a consistent succession of prophets and apostles, which God has promised will not be broken before the Second Coming of Christ (Dan 2:44).[56]

Each member of the LDS Church is also confirmed a member of the church following baptism and given the "gift of the Holy Ghost" by which each member is encouraged to develop a personal relationship with that divine being and receive personal revelation for their own direction and that of their family.[57] The Latter Day Saint concept of revelation includes the belief that revelation from God is available to all those who earnestly seek it with the intent of doing good. It also teaches that everyone is entitled to personal revelation with respect to his or her stewardship (leadership responsibility). Thus, parents may receive inspiration from God in raising their families, individuals can receive divine inspiration to help them meet personal challenges, church officers may receive revelation for those whom they serve, and so forth.

The important consequence of this is that each person may receive confirmation that particular doctrines taught by a prophet are true, as well as gain divine insight in using those truths for their own benefit and eternal progress. In the church, personal revelation is expected and encouraged, and many converts believe that personal revelation from God was instrumental in their conversion.[58] Joseph F. Smith, the sixth president of the LDS Church, summarized this church's belief concerning revelation by saying, "We believe... in the principle of direct revelation from God to man" (Smith, 362).[59]

Quakers

Quakers, known formally as the Religious Society of Friends, are generally united by a belief in each human's ability to experience the light within or see "that of God in every one."[60] Most Quakers believe in continuing revelation: God continuously reveals truth directly to individuals. George Fox said, "Christ has come to teach His people Himself."[61] Friends often focus on feeling the presence of God. As Isaac Penington wrote in 1670, "It is not enough to hear of Christ, or read of Christ, but this is the thing – to feel him to be my root, my life, and my foundation...."[62] Quakers reject the idea of priests and believe in the priesthood of all believers. Some express their concept of God using phrases such as "the inner light", "inward light of Christ", or "Holy Spirit". Quakers first gathered around George Fox in the mid–17th century and belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations.[63]

Deism

With the development of rationalism, materialism, and atheism during the Age of Enlightenment in Europe beginning about the mid-17th century, the concept of supernatural revelation began to face skepticism. In The Age of Reason (1794–1809), Thomas Paine developed the theology of deism, rejecting the possibility of miracles and arguing that a revelation may be considered valid only for the original recipient, with all else being hearsay.[64]

Hinduism

Śruti, Sanskrit for "that which is heard", refers to the body of most authoritative, ancient religious texts comprising the central canon of Hinduism.[65] It includes the four Vedas including its four types of embedded texts—the Samhitas, the early Upanishads.[66] Śrutis have been variously described as a revelation through anubhava (direct experience),[67] or of primordial origins realized by ancient Rishis.[65] In Hindu tradition, they have been referred to as apauruṣeya (not created by humans).[68] The Śruti texts themselves assert that they were skillfully created by Rishis (sages), after inspired creativity, just as a carpenter builds a chariot.[69]

Islam

Muslims believe that God (Arabic: ألله Allah) revealed his final message to all of existence through Muhammad via the angel Gabriel.[70] Muhammad is considered to have been the Seal of the Prophets and the last revelation, the Qur'an, is believed by Muslims to be the flawless final revelation of God to humanity, valid until the Last Day. The Qur'an claims to have been revealed word by word and letter by letter.[71]

Muslims hold that the message of Islam is the same as the message preached by all the messengers sent by God to humanity since Adam. Muslims believe that Islam is the oldest of the monotheistic religions because it represents both the original and the final revelation of God to Abraham, Moses, David, Jesus, and Muhammad.[72][73] Likewise, Muslims believe that every prophet received revelation in their lives, as each prophet was sent by God to guide mankind. Jesus is significant in this aspect as he received revelation in a twofold aspect, as Muslims believe he preached the Gospel while also having been taught the Torah.[74][75]

According to Islamic traditions, Muhammad began receiving revelations from the age of 40 that were delivered through the angel Gabriel over the last 23 years of his life. The content of these revelations, known as the Qur'an,[76] was memorized and recorded by his followers and compiled from dozens of hafiz as well as other various parchments or hides into a single volume shortly after his death. In Muslim theology, Muhammad is considered equal in importance to all other prophets of God and to make distinction among the prophets is a sin, as the Qur'an itself promulgates equality between God's prophets.[77]

Many scholars have made the distinction between revelation and inspiration, which according to Muslim theology, all righteous people can receive. Inspiration refers to God inspiring a person to commit some action, as opposed to revelation, which only the prophets received.[78][79] Moses's mother, Jochebed, being inspired to send the infant Moses in a cradle down the Nile river is a frequently cited example of inspiration,[80][81][82] as is Hagar searching for water for the infant Ishmael.[83][84]

Judaism

The term revelation is used in two senses in Jewish theology; (1) what in rabbinical language is called Gilluy Shekinah, a manifestation of God by some wondrous act of his which overawes man and impresses him with what he sees, hears, or otherwise perceives of his glorious presence; or (2) a manifestation of his will through oracular words, signs, statutes, or laws.[85][86]

In Judaism, issues of epistemology have been addressed by Jewish philosophers such as Saadiah Gaon (882–942) in his Book of Beliefs and Opinions; Maimonides (1135–1204) in his Guide for the Perplexed; Samuel Hugo Berman, professor of philosophy at the Hebrew University; Joseph Dov Soloveitchik (1903–1993), talmudic scholar and philosopher; Neil Gillman, professor of philosophy at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, and Elliot N. Dorff, professor of philosophy at the American Jewish University.[86]

One of the major trends in modern Jewish philosophy was the attempt to develop a theory of Judaism through existentialism. One of the primary players in this field was Franz Rosenzweig. His major work, Star of Redemption, expounds a philosophy in which he portrays the relationships between God, humanity and world as they are connected by creation, revelation and redemption.[86] Conservative Jewish philosophers Elliot N. Dorff and Neil Gillman take the existentialist philosophy of Rosenzweig as one of their starting points for understanding Jewish philosophy. (They come to different conclusions, however.)[86]

Rabbinic Judaism, and contemporary Orthodox Judaism, hold that the Torah (Pentateuch) extant today is essentially the same one that the whole of the Jewish people received on Mount Sinai, from God, upon their Exodus from Egypt.[87] Beliefs that God gave a "Torah of truth" to Moses (and the rest of the people), that Moses was the greatest of the prophets, and that the Law given to Moses will never be changed, are three of the Thirteen Principles of Faith of Orthodox Judaism according to Maimonides.[86]

Orthodox Judaism believes that in addition to the written Torah, God also revealed to Moses a set of oral teachings, called the Oral Torah. In addition to this revealed law, Jewish law contains decrees and enactments made by prophets, rabbis, and sages over the course of Jewish history. Haredi Judaism tends to regard even rabbinic decrees as being of divine origin or divinely inspired, while Modern Orthodox Judaism tends to regard them as being more potentially subject to human error, although due to the Biblical verse "Do not stray from their words" ("Deuteronomy 17:11) it is still accepted as binding law.[86]

Conservative Judaism tends to regard both the Torah and the Oral law as not verbally revealed. The Conservative approach tends to regard the Torah as compiled by redactors in a manner similar to the Documentary Hypothesis. However, Conservative Jews also regard the authors of the Torah as divinely inspired, and many regard at least portions of it as originating with Moses. Positions can vary from the position of Joel Roth, following David Weiss HaLivni, that while the Torah originally given to Moses on Mount Sinai became corrupted or lost and had to be recompiled later by redactors, the recompiled Torah is nonetheless regarded as fully Divine and legally authoritative, to the position of Gordon Tucker that the Torah, while Divinely inspired, is a largely human document containing significant elements of human error, and should be regarded as the beginning of an ongoing process which is continuing today. Conservative Judaism regards the Oral Law as divinely inspired, but nonetheless subject to human error.[86]

Reform and Reconstructionist Jews also accept the Documentary Hypothesis for the origin of the Torah, and tend to view all of the Oral law as an entirely human creation. Reform believe that the Torah is not a direct revelation from God, but is a document written by human ancestors, carrying human understanding and experience, and seeking to answer the question: 'What does God require of us?'. They believe that, though it contains many 'core-truths' about God and humanity, it is also time bound. They believe that God's will is revealed through the interaction of humanity and God throughout history, and so, in that sense, Torah is a product of an ongoing revelation. Reconstructionist Judaism denies the notion of revelation entirely.[86]

Prophets

Although the Nevi'im (the books of the Prophets) are considered divine and true, this does not imply that the books of the prophets are always read literally. Jewish tradition has always held that prophets used metaphors and analogies. There exists a wide range of commentaries explaining and elucidating those verses consisting of metaphor. Rabbinic Judaism regards Moses as the greatest of the prophets, and this view is one of the Thirteen Principles of Faith of traditional Judaism. Consistent with the view that revelation to Moses was generally clearer than revelation to other prophets, Orthodox views of revelation to prophets other than Moses have included a range of perspectives as to directness. For example, Maimonides in The Guide for the Perplexed said that accounts of revelation in the Nevi'im were not always as literal as in the Torah and that some prophetic accounts reflect allegories rather than literal commands or predictions.[88]

Conservative Rabbi and philosopher Abraham Joshua Heschel (1907–1972), author of a number of works on prophecy, said that, "Prophetic inspiration must be understood as an event, not as a process."[89] In his work God in Search of Man, he discussed the experience of being a prophet. In his book Prophetic Inspiration After the Prophets: Maimonides and Others, Heschel references to continued prophetic inspiration in Jewish rabbinic literature following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem and into medieval and even Modern times. He wrote that:[90]

- "To convey what the prophets experienced, the Bible could either use terms of descriptions or terms of indication. Any description of the act of revelation in empirical categories would have produced a caricature. That is why all the Bible does is to state that revelation happened. How it happened is something they could only convey in words that are evocative and suggestive."[91]

Sikhism

The Guru Granth Sahib is considered to be a divine revelation by God to the Sikh gurus. In various verses of Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh gurus themselves state that they merely speak what the divine teacher (God) commands them to speak. Guru Nanak frequently used to tell his ardent follower Mardana "Oh Mardana, play the rabaab the Lord's word is descending onto me."[92]

In certain passages of Guru Granth Sahib, it is clearly said the authorship is of divine origin and the gurus are merely the channel through which such revelations came.[92]

Revealed religion

Revealed religions have religious texts which they view as divinely or supernaturally revealed or inspired. For instance, Orthodox Jews, Christians, and Muslims believe that the Torah was received from God on biblical Mount Sinai.[93][94] Most Christians believe that both the Old Testament and the New Testament were inspired by God. Muslims believe the Quran was revealed by God to Muhammad word by word through the angel Gabriel (Jibril).[95][96] In Hinduism, the Vedas are considered apauruṣeya, "not human compositions", and are supposed to have been directly revealed, and thus are called śruti, "what is heard". Hindus also consider the Bhagavad Gita to contain direct revelation from Krishna.[97][63]

A revelation communicated by a supernatural entity reported as being present during the event is called a vision. Direct conversations between the recipient and the supernatural entity,[98] or physical marks such as stigmata, have been reported. In rare cases, such as that of Saint Juan Diego, physical artifacts accompany the revelation.[99] The Roman Catholic concept of interior locution includes just an inner voice heard by the recipient.[63]

In the Abrahamic religions, the term is used to refer to the process by which God reveals knowledge of himself, his will, and his divine providence to the world of human beings.[100] In secondary usage, revelation refers to the resulting human knowledge about God, prophecy, and other divine things. Revelation from a supernatural source plays a less important role in some other religious traditions such as Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism.[63]

See also

References

- ↑ von Stuckrad, Kocku, ed (2007). "The Brill Dictionary of Religion". The Brill Dictionary of Religion. Leiden and Boston: Brill Publishers. doi:10.1163/1872-5287_bdr_SIM_00056. ISBN 9789004124332.

- ↑ "انواع وحی" (in fa). https://www.porseman.com/article/%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%B9-%D9%88%D8%AD%D9%8A/42800.

- ↑ "معناى وحى و اقسام آن" (in fa). https://www.porseman.com/article/%D9%85%D8%B9%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%89-%D9%88%D8%AD%D9%89-%D9%88-%D8%A7%D9%82%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%85-%D8%A2%D9%86/20231.

- ↑ Staniloae, Staniloae (2000). Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: The Experience of God v. 1 (Orthodox Dogmatic Theology, Volume 1 : Revelation and Knowledge of the Triune God. T.& T.Clark Ltd. ISBN 978-0917651700.

- ↑ "از مکاشفه چه میدانیم؟" (in fa). 20 April 2016. https://www.hawzahnews.com/news/376932/%D8%A7%D8%B2-%D9%85%DA%A9%D8%A7%D8%B4%D9%81%D9%87-%DA%86%D9%87-%D9%85%DB%8C-%D8%AF%D8%A7%D9%86%DB%8C%D9%85.

- ↑ "اگزیستانسیالیسم به زبان ساده" (in fa). 2 May 2023. https://bookapo.com/mag/lifestyle/existentialism/.

- ↑ Nietzsche, Friedrich (1911). Levy, Oscar. ed. The Complete Works of Friedrich Nietzsche. Vol. 17 Ecce Homo. New York: The MacMillan Company. pp. 101–102. https://archive.org/details/TheCompleteWorksOfFriedrichNietzschevol.17-EcceHomo. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- ↑ "Ptesáŋwiŋ, espírito sagrado dos indígenas da América do Norte" (in it). 16 September 2023. https://historiablog.org/2023/09/15/ptesanwin-espirito-sagrado-dos-indigenas-da-america-do-norte/.

- ↑ "Huitzilopochtli - Aztec God of War & Sun Worship" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/topic/Huitzilopochtli.

- ↑ "حقایق کمتر شنیده شده درباره تک چشمی که در آخرالزمان ظهور میکند؛ دجال چه فتنهای میکند و چگونه کشته میشود؟" (in fa). https://www.yjc.ir/fa/news/7535183/%D8%AD%D9%82%D8%A7%DB%8C%D9%82-%DA%A9%D9%85%D8%AA%D8%B1-%D8%B4%D9%86%DB%8C%D8%AF%D9%87-%D8%B4%D8%AF%D9%87-%D8%AF%D8%B1%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%87-%D8%AA%DA%A9-%DA%86%D8%B4%D9%85%DB%8C-%DA%A9%D9%87-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A2%D8%AE%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B2%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%B8%D9%87%D9%88%D8%B1-%D9%85%DB%8C%E2%80%8C%DA%A9%D9%86%D8%AF-%D8%AF%D8%AC%D8%A7%D9%84-%DA%86%D9%87-%D9%81%D8%AA%D9%86%D9%87%E2%80%8C%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D9%85%DB%8C%E2%80%8C%DA%A9%D9%86%D8%AF-%D9%88-%DA%86%DA%AF%D9%88%D9%86%D9%87-%DA%A9%D8%B4%D8%AA%D9%87-%D9%85%DB%8C%E2%80%8C%D8%B4%D9%88%D8%AF.

- ↑ "«ظهور دوم مسیح بر زمین»؛ بومیان لاکوتا تولد بوفالوی سفید در پارک ملی یلواستون را جشن میگیرند" (in fa). 15 June 2024. https://parsi.euronews.com/2024/06/15/birth-of-rare-white-buffalo-calf-in-yellowstone-park-fulfills-lakota-prophecy.

- ↑ "تا مرز ترس - صخرهی برج شیاطین" (in fa). https://www.karnaval.ir/blog/%D8%AA%D8%A7-%D9%85%D8%B1%D8%B2-%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%B3-%D8%B5%D8%AE%D8%B1%D9%87-%DB%8C-%D8%A8%D8%B1%D8%AC-%D8%B4%DB%8C%D8%A7%D8%B7%DB%8C%D9%86.

- ↑ "تطبیق انگارۀ وحی در عهدین و قرآن کریم" (in fa). الهیات تطبیقی 3 (7). 20 March 2012. https://coth.ui.ac.ir/article_15713.html. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ↑ Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2000). Isaiah 1-39: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary. Anchor Yale Bible. 19. Yale University Press. pp. 215-221. ISBN 978-0-300-14018-7.

- ↑ "1 Kings 22 / Hebrew – English Bible / Mechon-Mamre". Mechon-mamre.org. http://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt09a22.htm.

- ↑ "وحی در عهد عتیق" (in fa). https://www.porseman.com/article/%D9%88%D8%AD%D9%8A-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%B9%D9%87%D8%AF-%D8%B9%D8%AA%D9%8A%D9%82/118765.

- ↑ "اثبات پذیری گزارههای دینی" (in fa). https://ensani.ir/fa/article/6741/%D8%A7%D8%AB%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D9%BE%D8%B0%DB%8C%D8%B1%DB%8C-%DA%AF%D8%B2%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%87-%D9%87%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D8%AF%DB%8C%D9%86%DB%8C.

- ↑ God in Search of Man

- ↑ نسرین, علم مهرجردی; محمدکاظم, شاکر (April 2013). "رابطه خدا با انسان؛ تمثل، تجسد یا تجلی؟" (in fa). انسان پژوهی دینی 9 (28). https://raj.smc.ac.ir/article_2276.html. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ↑ Ninian Smart (1999) "Mysticism" in The Norton Dictionary of Modern Thought (W. W. Norton & Co. Inc.) p. 555

- ↑ "نقش فرشته و پیامبر در وحی از نگاه قرآن و روایات" (in fa). http://ensani.ir/fa/article/69011/%D9%86%D9%82%D8%B4-%D9%81%D8%B1%D8%B4%D8%AA%D9%87-%D9%88-%D9%BE%DB%8C%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A8%D8%B1-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D9%88%D8%AD%DB%8C-%D8%A7%D8%B2-%D9%86%DA%AF%D8%A7%D9%87-%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A2%D9%86-%D9%88-%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%A7%D8%AA.

- ↑ "چگونگی وحی نبوت از دیدگاه قرآن و روایات" (in fa). فصلنامه کلام اسلامی 21 (82). 22 August 2012. https://www.kalamislami.ir/article_61842.html. Retrieved 22 December 2024.

- ↑ "تشخیص وحی از دیگر امور ماورائی" (in fa). https://www.porseman.com/article/%D8%AA%D8%B4%D8%AE%D9%8A%D8%B5-%D9%88%D8%AD%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D8%B2-%D8%AF%D9%8A%DA%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B1-%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%8A/39054.

- ↑ "Book of Certitude: Dating the Iqan". Kalimat Press. 1995. http://bahai-library.com/wilmette_kitab_iqan_date.

- ↑ The Writings of Baha'u'llah, Published in The Bahá'í World. 14. Bahá'í World Centre. pp. 620–32. http://bahai-library.com/khavari_writings_bahaullah. Retrieved 2007-02-26.

- ↑ "A new volume of Bahá'í sacred writings, recently translated and comprising Bahá'u'lláh's call to world leaders, is published". Bahá'í World Centre. May 2002. http://www.bahaiworldnews.org/story.cfm?storyid=163.

- ↑ Taherzadeh, A. (1976). The Revelation of Bahá'u'lláh, Volume 1: Baghdad 1853–63. Oxford, UK: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-270-8.

- ↑ For extended comments on the divine revelation of the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, and `Abdu'l-Bahá see Number of tablets revealed by Bahá'u'lláh by Robert Stockman and Juan Cole, Numbers and Classifications of Sacred Writings texts by the Universal House of Justice, and Horace Holley's preface of The Bahá'í Revelation, including Selections from the Bahá'í Holy Writings and Talks by `Abdu'l-Bahá.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 67". Vatican.va. https://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p1s1c2a1.htm#66.

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 426, 516.

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed., para. 108

- ↑ Geisler & Nix (1986). A General Introduction to the Bible. Moody Press, Chicago. ISBN 0-8024-2916-5.

- ↑ Coleman, R. J. (1975). "Biblical Inerrancy: Are We Going Anywhere?". Theology Today 31 (4): 295. doi:10.1177/004057367503100404.

- ↑ "Cardinal Augustin Bea, "Vatican II and the Truth of Sacred Scripture"". http://www.scotthahn.com/download/attachment/2516.

- ↑ "Second Vatican Council, Dei Verbum (Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation), 11". Vatican.va. https://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19651118_dei-verbum_en.html.

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, 105–108". Vatican.va. https://www.vatican.va/archive/ENG0015/__PP.HTM.

- ↑ Dei Verbum, 12

- ↑ Second Helvetic Confession, Of the Holy Scripture Being the True Word of God; Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, Online text

- ↑ Wikisource:Confession of Faith Ratification Act 1690

- ↑ John 10:34–36

- ↑ 2 Timothy 3:16

- ↑ 2 Peter 1:20–21

- ↑ 2 Peter 3:15–16

- ↑ Systematic Theology I, by Paul Tillich, University of Chicago Press, 205. 0-226803-37-6. Paul Tillich (1967). Systematic Theology. University of Chicago Press. p. 307. ISBN 0-226-80336-8.

- ↑ "CCC, 36–38". Vatican.va. http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p1s1c1.htm.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Holy See, Dei verbum: Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, published during the Second Vatican Council on 18 November 1965, accessed on 19 August 2025

- ↑ "CCC, 65–73". Vatican.va. http://www.vatican.va/archive/ccc_css/archive/catechism/p1s1c2a1.htm.

- ↑ Bushman, Richard L. (2008). Mormonism: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 27. doi:10.1093/actrade/9780195310306.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-531030-6. https://archive.org/details/mormonismverysho00bush_512.

- ↑ Dallin H. Oaks (Feb 1992). "The Divinely Inspired Constitution". Ensign. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/ensign/1992/02/the-divinely-inspired-constitution?lang=eng.

- ↑ See D&C 101:77–80

- ↑ "Prophets". churchofjesuschrist.org. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-topics/prophets?lang=eng.

- ↑ "Revelation". churchofjesuschrist.org. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/scriptures/bd/revelation?lang=eng.

- ↑ Eph 2:20 and 4:11–14, see also Matt 16:17–18

- ↑ "Gospel Principles Chapter 16: The Church of Jesus Christ in Former Times". churchofjesuschrist.org. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-principles/chapter-16-the-church-of-jesus-christ-in-former-times?lang=eng.

- ↑ "Gospel Principles Chapter 17: The Church of Jesus Christ Today". churchofjesuschrist.org. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-principles/chapter-17-the-church-of-jesus-christ-today?lang=eng.

- ↑ "The Church of Jesus Christ". churchofjesuschrist.org. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/topics/church-organization/the-church-of-jesus-christ?lang=eng.

- ↑ "Gospel Principles Chapter 21: The Gift of the Holy Ghost". churchofjesuschrist.org. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/gospel-principles/chapter-21-the-gift-of-the-holy-ghost?lang=eng.

- ↑ "Continuing Revelation". Mormon.org. http://www.mormon.org/learn/0,8672,1084-1,00.html.

- ↑ Smith, Joseph F. (November 2007). "41: Continuing Revelation for the Benefit of the Church". Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith. Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. p. 362. ISBN 978-1-59955-103-6. https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/manual/teachings-joseph-f-smith?lang=eng.

- ↑ Fox, George (1903). George Fox's Journal. Isbister and Company Limited. pp. 215–216. https://archive.org/stream/georgefoxsjourn00nicogoog#page/n245. "This is the word of the Lord God to you all, and a charge to you all in the presence of the living God; be patterns, be examples in all your countries, places, islands, nations, wherever you come; that your carriage and life may preach among all sorts of people and to them: then you will come to walk cheerfully over the world, answering that of God in every one; whereby in them ye may be a blessing, and make the witness of God in them to bless you: then to the Lord God you will be a sweet savour, and a blessing."

- ↑ George Fox (1694). George Fox: An Autobiography (George Fox's Journal). Archived from the original.

- ↑ "Isaac Penington to Thomas Walmsley (1670)". Quaker Heritage Press.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 63.3 "ادیان وحیانی، صفحه ۳۴ تا ۶۸" (in fa). https://srb.iau.ir/file/download/page/1732610655-67458a5fdaf72-5.pdf.

- ↑ Paine, Thomas (1987). Foot, Michael; Kramnick, Isaac. eds. The Thomas Paine Reader. New York: Penguin Books. p. 403. ISBN 0-14-044496-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=GDRt70vGw9YC.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 James Lochtefeld (2002), "Shruti", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 2: N–Z, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 9780823931798, page 645

- ↑ Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty (1988), Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-1867-6, pages 2–3

- ↑ Michael Myers (2013). Brahman: A Comparative Theology. Routledge. pp. 104–112. ISBN 978-1-136-83572-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=JfncAAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ P Bilimoria (1998), 'The Idea of Authorless Revelation', in Indian Philosophy of Religion (Editor: Roy Perrett), ISBN 978-94-010-7609-8, Springer Netherlands, pages 3, 143–166

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe (2002), Handbook of Oriental Studies, BRILL Academic, ISBN 978-9004125568, pages 13–14

- ↑ Watton (1993), "Introduction"

- ↑ حیدری, فهیمه خضر (22 December 2017). "آیا محمد خاتم پیامبران است؟" (in fa). رادیو فردا. https://www.radiofarda.com/a/taboo-e60-on-finality/28931779.html.

- ↑ Esposito (2002b), pp.4–5

- ↑ Quran 42:13

- ↑ "نقش فرشته و پیامبر در وحی از نگاه قرآن و روایات" (in fa). https://ensani.ir/fa/article/69011/%D9%86%D9%82%D8%B4-%D9%81%D8%B1%D8%B4%D8%AA%D9%87-%D9%88-%D9%BE%DB%8C%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A8%D8%B1-%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D9%88%D8%AD%DB%8C-%D8%A7%D8%B2-%D9%86%DA%AF%D8%A7%D9%87-%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A2%D9%86-%D9%88-%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%A7%D8%AA.

- ↑ "لوازم و پیامدهای نظریه تجربهگرایی وحی" (in fa). https://ensani.ir/fa/article/6717/%D9%84%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%B2%D9%85-%D9%88-%D9%BE%DB%8C%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%AF%D9%87%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D9%86%D8%B8%D8%B1%DB%8C%D9%87-%D8%AA%D8%AC%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%87-%DA%AF%D8%B1%D8%A7%DB%8C%DB%8C-%D9%88%D8%AD%DB%8C.

- ↑ The term Qur'an was first used in the Qur'an itself. There are two different theories about the term and its formation that are discussed in Quran

- ↑ Quran 3:84

- ↑ "وحی ، الهام ، و مکاشفه چه هستند و چه تفاوتها و شباهتهایی با هم دارند و ارزش معرفتی آنها چگونه است؟" (in fa). 1398. https://maab.iki.ac.ir/node/1163.

- ↑ "تفاوت وحی با مکاشفه" (in fa). https://www.porseman.com/article/%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%A7%D9%88%D8%AA-%D9%88%D8%AD%D9%8A-%D8%A8%D8%A7-%D9%85%D9%83%D8%A7%D8%B4%D9%81%D9%87/42908.

- ↑ "ماجرای تولد موسی (ع) و نگهداری او" (in fa). https://rasekhoon.net/article/show/128144.

- ↑ "حکایتی از لحظه تولّد موسی علیه السلام" (in fa). https://hawzah.net/fa/Book/View/45327/35724/%D8%AD%DA%A9%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%AA%DB%8C-%D8%A7%D8%B2-%D9%84%D8%AD%D8%B8%D9%87-%D8%AA%D9%88%D9%84%D9%91%D8%AF-%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B3%DB%8C-%D8%B9%D9%84%DB%8C%D9%87-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%85.

- ↑ "مادر موسي چرا و چگونه موسي را به نيل انداخت؟" (in fa). https://pasokhgo.valiasr-aj.com/porseman/showquestion.php?code=5072.

- ↑ "هاجر سلام الله علیها مادر دو ذبیح" (in fa). https://hawzah.net/fa/Article/View/93229/%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%AC%D8%B1_%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%85_%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87_%D8%B9%D9%84%DB%8C%D9%87%D8%A7_%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%B1_%D8%AF%D9%88_%D8%B0%D8%A8%DB%8C%D8%AD.

- ↑ "سعی هاجر: تلاش و حرکت ماندگار" (in fa). میقات حج 17 (68). 22 June 2009. https://miqat.hajj.ir/article_37978.html. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ↑ ""Revelation", Jewish Encyclopedia". Jewishencyclopedia.com. http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12713-revelation.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 86.2 86.3 86.4 86.5 86.6 86.7 "REVELATION" (in en). https://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/12713-revelation.

- ↑ Rabbi Nechemia Coopersmith and Rabbi Moshe Zeldman: "Did God Speak at Sinai", Aish HaTorah

- ↑ Jewish Theology and Process Thought (eds. Sandra B. Lubarsky & David Ray Griffin). SUNY Press, 1996.

- ↑ Heschel, Abraham Joshua (1955). God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism. Noonday. p. 209. ISBN 0-374-51331-7. https://archive.org/details/godinsearchofman0000hesc/page/209.

- ↑ Aryeh Kaplan, The Handbook of Jewish Thought (1979). e Maznaim: p. 9.

- ↑ Heschel, Abraham Joshua (1987). God in Search of Man: A Philosophy of Judaism. ason Aronson Inc.. ISBN 0-87668-955-1.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 "متون مقدس دین سیک" (in fa). https://alefbalib.com/Metadata/341979/%D9%85%D8%AA%D9%88%D9%86-%D9%85%D9%82%D8%AF%D8%B3-%D8%AF%DB%8C%D9%86-%D8%B3%DB%8C%DA%A9.

- ↑ Beale G.K., The Book of Revelation, NIGTC, Grand Rapids – Cambridge 1999. ISBN 0-8028-2174-X

- ↑ Esposito, John L. (2002). What Everyone Needs to Know about Islam. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9780195157130. OCLC 49902111.

- ↑ Lambert, Gray (2013). The Leaders Are Coming!. WestBow Press. p. 287. ISBN 9781449760137. https://books.google.com/books?id=sV0mAgAAQBAJ&q=%22Muslims+believe+that+the+Quran+was+verbally+revealed%22&pg=PA287.

- ↑ Roy H. Williams; Michael R. Drew (2012). Pendulum: How Past Generations Shape Our Present and Predict Our Future. Vanguard Press. p. 143. ISBN 9781593157067. https://books.google.com/books?id=mygRHh6p40kC&q=%22Muslims+believe+that+the+Quran+was+verbally+revealed%22&pg=PA143.

- ↑ Miller, Barbara Stoler; Moser, Barry (1986) (in English). The Bhagavad Gītā : Krishna's counsel in time of war. Internet Archive. New York : Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-06468-2. https://archive.org/details/bhagavadgita0022cm.

- ↑ Michael Freze, 1993, Voices, Visions, and Apparitions, OSV Publishing ISBN 0-87973-454-X p. 252

- ↑ Michael Freze, 1989 They Bore the Wounds of Christ ISBN 0-87973-422-1

- ↑ "Revelation | Define Revelation at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/revelation.

Further reading

- Wilhelm, Joseph (1906). "Book 1: Part 1: Chapters I-IV (Divine Revelation)". A Manual Of Catholic Theology. Benzinger Brothers.

External links

|

KSF

KSF