Great Depression

From Conservapedia

From Conservapedia

The Great Depression was a severe, worldwide economic downturn lasting from 1929 to the early 1940s. The primary cause was the failure of the Fed to carry out its given role of preventing bank runs. Nearly half the nation's banks failed, as panicked depositors withdrew their life savings, reducing the money supply and retarding investment. Then, things were made still worse by government intervention, i.e., the largest-ever peacetime tax increase, an increase in tariffs, massive public works projects, wage and price controls, and "increased bank-reserve requirements".[1]

- Milton Friedman said, "Roosevelt's policies were very destructive. Roosevelt's policies made the depression longer and worse than it otherwise would have been. What pulled us out of the depression was the natural resilience of the economy plus WW2."[2]

- "Hoover-nomics and FDR’s New Deal created the longest and deepest economic downturn in U.S. history." Raymond Keating

- The recession created by the collapse of the stock market was improving by 1930 (unemployment was down to 6%), but was possibly worsened by the Smoot-Hawley Tariff bill. [1]

Contents

- 1 Causes

- 2 Prelude to the Depression

- 3 The Stock Market Crash

- 4 Discussion of remedial measures

- 5 Attempts to stimulate the economy

- 6 Boom or Bust Cycles

- 7 World Trade

- 8 Why the "Great" Depression?

- 9 The Banking Crisis

- 10 The Drought

- 11 The New Deal

- 12 Recovery

- 13 See also

- 14 Bibliography

- 15 External links

- 16 References

- 17 External links

In the United States (and in most other countries), the Depression had a number of very grave symptoms:

- GDP fell drastically, with declines of 30-50% in most countries.

- Prices for commodities like crops, petroleum, raw materials and coal fell very sharply. This was deflation and it made the burden of debt higher and sabotaged long-term planning.

- Unemployment soared, with the highest rates in heavy manufacturing. It reached 20-30% in major countries.[3]

- Wage rates did NOT fall sharply, but hours per week of full-time workers fell. Workers were very reluctant to quit their jobs to look for a better one.

- Older workers without jobs were rarely hired; if they had jobs they delayed retirement.

- Teenagers had a very difficult time finding a first job; many stayed longer in school.

- Many men who were the breadwinner lost that role; many deserted their families and went on the road.

- Thousands of small banks in the U.S. closed—but none in Canada or Britain.

- When a bank closed its assets were sold off, and (in the U.S.) depositors after a few months received on average 85% of their deposits.

- Banks refused to lend money, and put their assets in safe government bonds.

- Farm income plunged more than half. Worst hit were export crops such as wheat, tobacco, and cotton.

- World trade (imports and exports) fell by three-fourths. In the U.S. imports and exports also fell but they were not large to begin with. Other countries were hurt much worse in this sector.

- Governments expecting the downturn to be short at first increased spending on public works, but soon ran out of money.

- Tax revenues for national, state and local governments fell sharply. Governments raised tax rates, which made it worse.

- Mortgages were foreclosed at record rates.

- Apartment owners often could not collect on rents; many went bankrupt.

- Private construction—both housing and commercial—plummeted, but public construction went up.

- Politically there was a widespread loss of faith in democracy; many countries turned to authoritarian regimes or dictatorships.

- The political results were negative for governments in power. In Britain this hurt the Labour party; in the U.S. it hurt the Republicans; in Canada it hurt the Liberal party.

Causes[edit]

Advocates of different economic systems have traded blame for the depression. The search for causes is important for two reasons. Socialists tend to call it a failure of the free market system, while advocates of free markets blame the depression on government efforts to transform the U.S. economy into Socialism. The political realignment of the New Deal Coalition could take an anti-business tone because bankers were in bad odor in 1933 (just as they are in 2009).

In historical terms, the "lessons" of the Great Depression have been applied to preventive measures, and in the Financial Crisis of 2008, helped determine what remedies to apply.

Milton Friedman[edit]

Friedman argues that the depression began as a normal cyclical downturn, but was made much worse when the money supply fell by a third, caused primarily by banking failures in the U.S. The Federal Reserve did not cause the depression, in Friedman's view, but failed to stop those bank failures when it could and should have done so in 1931–33. In Friedman's view, the Federal Reserve failed to do precisely what it was created to do, prevent a contraction in the money supply (monetary deflation) and prevent so many bank failures. Economist Ben Bernanke adopted the Friedman view, and when the Financial Crisis of 2008 hit, Bernanke, as Chairman of the Federal Reserve, made it a central goal to save the major banks using a trillion dollars in cash and credit from the Fed and from the $700 billion TARP program of October 2008 that Congress approved after President George W. Bush made an urgent appeal.

Austrian School[edit]

- As documented so well by free-market economists Ludwig von Mises, Friedrich Hayek, and Murray Rothbard, during the 1920s, the Federal Reserve Board, exercising its power to expand the money supply, caused an inflationary binge — an action which created a false aura of prosperity. When the political authorities — faced with this inflationary threat and restrained by the gold standard — finally ceased the monetary expansion near the end of the decade, the inevitable economic hangover was reflected in the 1929 stock market crash and in generally depressed economic conditions. In other words, contrary to the indoctrination which the American people have received from their political authorities, the Great Depression was not the failure of America's free-enterprise system — it was the failure of political manipulation of money and credit.

- Faced with the Great Depression — a depression which had been caused by government itself — Roosevelt's "solution" was to implement economic planning. Economist Jacob G. Hornberger has stated, "Under the banner of 'saving America's free-enterprise system,' FDR was directly responsible for the abandonment of America's 150-year history of free enterprise.[4]

Prelude to the Depression[edit]

The Great Depression has central place in twentieth century economic history. In its shadow, all other depressions are insignificant. Whether assessed by the relative shortfall of production from trend, by the duration of slack production, or by the product-depth times duration-of these two measures, the Great Depression is an order of magnitude larger than other depressions: it is off the scale. All other depressions and recessions are from an aggregate perspective (although not from the perspective of those left unemployed or bankrupt) little more than ripples on the tide of ongoing economic growth. The Great Depression cast the survival of the economic system, and the political order, into serious doubt.

As early as 1925, then-Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover had warned President Coolidge that stock market speculation was getting out of hand. Yet in his final State of the Union Address, Coolidge saw no reason for alarm. "No Congress...ever assembled has met with a more pleasing prospect than that which appears at the present time"...said Coolidge early in 1929. "In the domestic field there is tranquility and contentment...and the highest record of prosperity in years."

Al Smith's campaign manager, General Motors executive John J. Raskob, agreed. In an article entitled "Everybody Ought to be Rich" Raskob declared, "Prosperity is in the nature of an endless chain and we can break it only by refusing to see what it is." President-elect Herbert Hoover disagreed. Even before his inauguration he urged the Federal Reserve to halt "crazy and dangerous" gambling on Wall Street by increasing the discount rate the Fed charged banks for speculative loans. He asked magazines and newspapers to run stories warning of the dangers of rampant speculation.

Once in the office, the new president ordered a reluctant Andrew Mellon, his holdover secretary of the treasury, to promote the purchase of bonds instead of stocks. He sent his friend Henry Robinson, a Los Angeles banker, to convey a cautionary message to the financiers of Wall Street—and received in return a long, scoffing memorandum from Thomas W. Lamont of J.P. Morgan and Company. When the Federal Reserve Board that August did take steps to check the flow of speculative credit, New York bankers defied Washington, the National City Bank alone promising $100 million in fresh loans. An angry Hoover let the president of the New York Stock Exchange know that he was thinking of regulatory steps to curb stock manipulation and other excesses. Yet he undercut his own threat by placing ultimate responsibility for such measures on New York State's new governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who was already contemplating running against Hoover.

Presidents in 1929 were not supposed to regulate Wall Street, or even talk about the gyrating market for fear of inadvertently setting off a panic. Hoover had his own reasons for keeping quiet. His conscience was pained after a friend took his advice to buy an issue that later nosedived. "To clear myself," the president told intimates, "I just bought it back and I have never advised anybody since."

By early September, 1929 the market was topping out, some eighty two points above its January plateau. In eighteen months, General Electric had tripled in value, reaching $396 per share. Other blue chips, fueled by more than $8 billion in brokers' loans, enjoyed similar rises. The last week of October, however, brought a terrible reckoning. On October 24 alone (Black Thursday), radio stocks lost 40% of their paper value. Montgomery Ward surrendered thirty-three points. Big bankers tried and failed to stem the dizzying decline in U.S. Steel, a bellwether stock.

The Stock Market Crash[edit]

For a more detailed treatment, see Stock market crash of 1929.

On Black Tuesday, the twenty-ninth, the market collapsed. In the words of a gray haired Stock Exchange guard, "They roared like a lot of lions and tigers. They hollered and screamed, they clawed at one another collars. It was like a bunch of crazy men. Every once in a while, when Radio or Steel or Auburn would take another tumble, you'd see some poor devil collapse and fall to the floor."

In a single day, sixteen million shares were traded—a record—and thirty billion dollars vanished into thin air. Westinghouse lost two thirds of its September value. DuPont dropped seventy points. The "Era of Get Rich Quick" was over. Jack Dempsey, America's first millionaire athlete, lost $3 million. Cynical New York hotel clerks asked incoming guests, "You want a room for sleeping or jumping?"

Discussion of remedial measures[edit]

The first instinct of governments and central banks faced with this gathering Depression began was to do nothing. Businessmen, economists, and politicians (memorably Secretary of the Treasury Mellon) expected the recession of 1929-1930 to be self-limiting. Earlier recessions had come to an end when the gap between actual and trend production was as large as in 1930. They expected workers with idle hands and capitalists with idle machines to try to undersell their still at-work peers. Prices would fall. When prices fell enough, entrepreneurs would gamble that even with slack demand production would be profitable at the new, lower wages. Production would then resume.

Throughout the decline—which carried production per worker down to a level 40 percent below that which it had attained in 1929, and which saw the unemployment rise to take in more than a quarter of the labor force—the government did not try to prop up aggregate demand. The Federal Reserve did not use open market operations to keep the money supply from falling. Instead the only significant systematic use of open market operations was in the other direction: to raise interest rates and discourage gold outflows after the United Kingdom abandoned the gold standard in the fall of 1931. The Federal Reserve thought it knew what it was doing: it was letting the private sector handle the Depression in its own fashion. It saw the private sector's task as the "liquidation" of the American economy. And it feared that expansionary monetary policy would impede the necessary private-sector process of readjustment.

Contemplating the wreck of his country's economy and his own political career, Herbert Hoover wrote bitterly in retrospect about those in his administration who had advised inaction during the downslide:

- The 'leave-it-alone liquidationists' headed by Secretary of the Treasury Mellon felt that government must keep its hands off and let the slump liquidate itself. Mr. Mellon had only one formula: 'Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate'. He held that even panic was not altogether a bad thing. He said: 'It will purge the rottenness out of the system. High costs of living and high living will come down. People will work harder, live a more moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people." There had never been a depression like this before, and his prediction that it would right itself was not based on any studies he did or any evidence he presented.

But Hoover had been one of the most enthusiastic proponents of "liquidationism" during the Great Depression. And the unwillingness to use policy to prop up the economy during the slide into the Depression was backed by a large chorus, and approved by the most eminent economists.

For example, from Harvard Joseph Schumpeter argued that there was a "presumption against remedial measures which work through money and credit. Policies of this class are particularly apt to produce additional trouble for the future." From Schumpeter's perspective, "depressions are not simply evils, which we might attempt to suppress, butforms of something which has to be done, namely, adjustment to change." This socially productive function of depressions creates "the chief difficulty" faced by economic policy makers. For "most of what would be effective in remedying a depression would be equally effective in preventing this adjustment."

From London, Friedrich Hayek found it:

- ...still more difficult to see what lasting good effects can come from credit expansion. The thing which is most needed to secure healthy conditions is the most speedy and complete adaptation possible of the structure of production.If the proportion as determined by the voluntary decisions of individuals is distorted by the creation of artificial demand resources [are] again led into a wrong direction and a definite and lasting adjustment is again postponed.The only way permanently to 'mobilise' all available resources is, thereforeto leave it to time to effect a permanent cure by the slow process of adapting the structure of production...

Hayek and company believed that enterprises are gambles which sometimes fail: a future comes to pass in which certain investments should not have been made. The best that can be done in such circumstances is to shut down those production processes that turned out to have been based on assumptions about future demands that did not come to pass. The liquidation of such investments and businesses releases factors of production from unprofitable uses; they can then be redeployed in other sectors of the technologically dynamic economy. Without the initial liquidation the redeployment cannot take place. And, said Hayek, depressions are this process of liquidation and preparation for the redeployment of resources.

As Schumpeter put it, policy does not allow a choice between depression and no depression, but between depression now and a worse depression later: "inflation pushed far enough [would] undoubtedly turn depression into the sham prosperity so familiar from European postwar experience, [and]... would, in the end, lead to a collapse worse than the one it was called in to remedy." For "recovery is sound only if it does come of itself. For any revival which is merely due to artificial stimulus leaves part of the work of depressions undone and adds, to an undigested remnant of maladjustment, new maladjustment of its own which has to be liquidated in turn, thus threatening business with another [worse] crisis ahead"

This doctrine—that in the long run the Great Depression would turn out to have been "good medicine" for the economy, and that proponents of stimulative policies were shortsighted enemies of the public welfare—drew anguished cries of dissent. British economist Ralph Hawtrey scorned those who, like Robbins and Hayek, wrote at the nadir of the Great Depression that the greatest danger the economy faced was inflation. It was, Hawtrey said, the equivalent of "Crying, 'Fire! Fire!' in Noah's flood."

John Maynard Keynes also tried to bury the liquidationists in ridicule. Milton Friedman in the 1930s and early 1940s was an avid Keynesian and indeed became a top advisor to the Treasury Department. In the 1950s he changed positions.

However, the "liquidationist" view carried the day. Even governments that had unrestricted international freedom of action—like France and the United States with their massive gold reserves—tended not to pursue expansionary monetary and fiscal policies on the grounds that such would reduce investor "confidence" and hinder the process of liquidation, reallocation, and the resumption of private investment.

Attempts to stimulate the economy[edit]

Refusing to accept the "natural" economic cycle in which a market crash was followed by cuts in business investment, production and wages, Hoover summoned industrialists to the White House on November 21, part of a round robin of conferences with business, labor, and farm leaders, and secured a promise to hold the line on wages. Henry Ford even agreed to increase workers' daily pay from six to seven dollars. From the nation's utilities, Hoover won commitments of $1.8 billion in new construction and repairs for 1930. Railroad executives made a similar pledge. Organized labor agreed to withdraw its latest wage demands.

The President ordered federal departments to speed up construction projects. He contacted all forty-eight state governors to make a similar appeal for expanded public works. He went to Congress with a $160 million tax cut, coupled with a doubling of resources for public buildings and dams, highways and harbors. In December 1929, Hoover's friend Julius Barnes of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce presided over the first meeting of the National Business Survey Conference, a task force of four hundred leading businessmen designated to enforce the voluntary agreements. Looking back at the year, the "New York Times" judged Commander Richard Byrd's expedition to the South Pole—not the Wall Street crash—the biggest news story of 1929.

Praise for Hoover's intervention was widespread. "No one in his place could have done more," concluded the "New York Times" in the spring of 1930, by which time the Little Bull Market had restored a measure of confidence on Wall Street. "Very few of his predecessors could have done as much." concluded the Times. On February 18 Hoover announced that the preliminary shock had passed, and that employment was again on the mend. In June, a delegation of bishops and bankers called at the White House to warn of spreading joblessness. Hoover reminded them of his successful conferences with business and labor, and the explosion of government activity and public works designed to alleviate suffering. "Gentlemen," he concluded, "you have come six weeks too late".

Boom or Bust Cycles[edit]

For most of our history Americans have been resigned to the "boom and bust" school of economics. When the economy got overheated and speculation ran rampant, a crash was unavoidable. Under such circumstances the best government could do was to do nothing that might make a bad thing worse. "Panics" had occurred in the 1830s under President Martin Van Buren, in the 1850s under James Buchanan, during Ulysses S. Grant's term in the 1870s and, most notably, under Grover Cleveland in the 1890s.

None of these presidents did much to stem the deflation in prices, contraction of investment, and loss of jobs that resulted—for the simple reason that standard economic theory held there was little if anything they could do. Then, in 1921, a post war slump led President Warren Harding to name Hoover as chairman of a special conference to deal with unemployment. "There is no economic failure so terrible in its import," Hoover declared at the time, "as that of a country possessing a surplus of every necessity of life in which numbers...willing and anxious to work are deprived of dire necessities. It simply cannot be if our moral and economic system is to survive.

This view explains President Hoover's vigorous counterattack in the wake of Wall Street's initial tumble. Not all of his advisers were so willing to abandon Boom and Bust theories. As late as 1930, Secretary of the Treasury Andrew Mellon held that a panic might not be such a bad thing. "It will purge the rottenness out of the system," he added. "High costs of living...will come down. People will work harder, live a moral life. Values will be adjusted, and enterprising people will pick up the wrecks from less competent people." Mellon lost out, however, and was packed off by President Hoover to the Court of Saint James.

World Trade[edit]

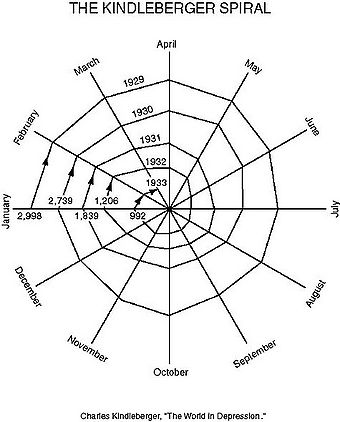

Every country began cutting imports, with the result that world trade spiraled downward, as the "Kindleberger spiral" demonstrates. The total imports of 75 countries declined from $3.0 billion in early 1929, shrinking every quarter to a low of $944 million in spring 1933.[5] The U.S. made matters worse with the Smoot-Hawley tariff of 1933, which restricted imports into the US. Canada, Britain, France and other countries retaliated by reducing their imports from the US.

Why the "Great" Depression?[edit]

Economists are still divided about what caused the Great Depression, and what turned a relatively mild downturn into a decade-long nightmare. Hoover himself emphasized the dislocations brought on by World War I, the rickety structure of American banking, excessive stock speculation and Congress' refusal to act on many of his proposals. The president's critics argued that in approving the Smoot-Hawley Tariff in the spring of 1930, he unintentionally raised barriers around U.S. products, worsened the plight of debtor nations and set off a round of retaliatory measures that crippled global trade.

Neither claim went far enough. In truth Hoover's celebration of technology failed to anticipate the end of a postwar building boom, or a glut of 26,000,000 new cars and other consumer goods flooding the market. Agriculture, mired in depression for much of the 1920s, was deprived of cash it needed to take part in the consumer revolution. At the same time, the average worker's wages of $1,500 a year failed to keep pace with the spectacular gains in productivity achieved since 1920. By 1929 production was outstripping demand.

The United States had too many banks, and too many of them played the stock market with depositors' funds, or speculated in their own stocks. Only a third or so belonged to the Federal Reserve System on which Hoover placed such reliance. In addition, government had yet to devise insurance for the jobless or income maintenance for the destitute. When unemployment resulted, buying power vanished overnight. Since most people were carrying a heavy debt-load even before the crash, the onset of recession in the spring of 1930 meant that they simply stopped spending.

Together government and business actually spent more in the first half of 1930 than the previous year. Yet frightened consumers cut back their expenditures by ten percent. A severe drought ravaged the agricultural heartland beginning in the summer of 1930. Foreign banks went under, draining U.S. wealth and destroying world trade. The combination of all these factors caused a downward spiral, as earning fell, domestic banks collapsed, and mortgages were called in. Hoover's hold the line policy in wages lasted little more than a year. Unemployment soared from five million in 1930 to over eleven million in 1931. A sharp recession had become the Great Depression.

Nevertheless, a large part of the puzzle remains: roughly half of Depression unemployment was concentrated among long-term unemployed who could not take advantage of subsidized relief-work schemes.

This form of unemployment, principally long-term and somewhat of a residual category is, in the eyes of Eichengreen and Hatton and their contributors, the key to the persistence of the Depression. Long-term unemployment was strongly present in those countries that suffered worst from the Depression, including non-European nations like Australia, Canada, and the United States and European nations like Britain, Germany, Italy, and the gold block nations of France and Belgium. Of these only Germany achieved a strong recovery from the Depression in the 1930s.

Long-term unemployment means that the burden of economic dislocation is unequally borne. Since the prices workers must pay often fall faster than wages, the welfare of those who remain employed frequently rises in a depression. Those who become and stay unemployed bear far more than their share of the burden of a depression. Moreover, the reintegration of the unemployed into even a smoothly-functioning market economy may prove difficult, for what employer would not prefer a fresh entrant into the labor force to someone out of work for years? The simple fact that an economy has recently undergone a period of mass unemployment may make it difficult to attain levels of employment and boom that a luckier economy attains as a matter of course.Once an economy had fallen deeply into the Great Depression, devalued exchange rates, prudent and moderate government budget deficits (as opposed to the deficits involved in fighting major wars), and the passage of time all appeared equally ineffective ways of dealing with long-term unemployment. Highly centralized and unionized labor markets like Australia's and decentralized and laissez-faire labor markets like that of the United States did equally poorly in dealing with long-term unemployment. Fascist "solutions" were equally unsuccessful, as the case of Italy shows, unless accompanied by rapid rearmament as in Germany.

Even today, economists have no clean answers to the question of why the private sector could not find ways to employ its long-term unemployed. The very extent of persistent unemployment in spite of different labor market structures and national institutions suggests that theories that find one key failure responsible should be taken with a grain of salt.

But should we be surprised that the long-term unemployed do not register their labor supply proportionately strongly? They might accurately suspect that they will be at the end of every selection queue. In the end it was the coming of World War II and its associated demand for military goods that made private sector employers wish to hire the long-term unemployed at wages they would accept.

The Banking Crisis[edit]

In the last weeks of his term, Hoover faced a desperate crisis of confidence as uncertain investors sought reassurance that the new administration would defend the gold standard. On February 17, 1933, the president wrote president-elect Roosevelt, seeking assurances that Roosevelt would balance the budget, combat inflation, and halt publication of loans made by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. Roosevelt, sensing that his discredited predecessor was trying to tie his hands, kept silent.

Soon banks in two dozen states began to totter. Hoover denounced corrupt bankers as worse than Al Capone ("He apparently was kind to the poor.") He proposed that the Federal Reserve guarantee every depositor's account in the nation. The idea of deposit insurance would eventually become law, but in February, 1933 the Reserve's governors preferred a general bank holiday instead. Hoover refused to take such a drastic action without Roosevelt's agreement. And FDR had his own agenda.

Twice on the night of March 3, Hoover telephoned the president-elect trying to persuade him to join in concerted action. FDR replied that governors were free to do what they wished on a state by state basis. A little after one in the morning, the Governors of New York and Illinois unilaterally suspended banking operations in their states. "We are at the end of our string," President Hoover remarked to his secretary that morning, "there is nothing more we can do."

Economist Milton Friedman points out the Federal Reserve Board did not do what it was created to do—act as lender of last resort to keep the money supply from shrinking—which caused the banking crisis.

The Drought[edit]

See Dust Bowl

The New Deal[edit]

see New Deal

Enforcement of the Antitrust Act was considered as an essential instrument to prevent cartels and trusts and combinations in restraint of trade which were supposed to be deadly to the system of free enterprise. During the fall election of 1932, Franklin Roosevelt called for strict enforcement of the Antitrust Act as part of his proposed New Deal. Yet immediately upon Roosevelt's election enforcement was suspended in order to cartelize every industry in America on the Italian corporative model.

In the United States, the depression caused the Republicans to lose the 1932 elections. Franklin D. Roosevelt, a Democrat, was not sure what to do, so he tried many different things at once. The "First New Deal" in 1933 enacted programs to deal with deflation, unemployment relief, the banking crisis, the farm crisis, international trade, and the overall economic malaise. The "Second Mew Deal" of 1934-35 involved a shift to the left, promoting labor unions, enacting Social Security, and nationalizing relief. Conservatives vigorously opposed the Second New Deal, but FDR was reelected in a landslide in 1936. In his second term, politics turned sour and only one new program was enacted (the minimum wage), as the economy plunged downward again in 1937–38. Full recovery came as the US rearmed for World War II.

Recovery[edit]

See also[edit]

- Herbert Hoover

- Fifth Party System

- Jobless recovery

- New Deal

- New Deal Bibliography

- Franklin D. Roosevelt

- The Forgotten Depression of 1920

Bibliography[edit]

- Beito David. Taxpayers in Revolt (1989)

- Bernanke, Ben S. "The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach," Journal of Money, Credit & Banking, Vol. 27, 1995 online edition

- Bernstein, Irving. Turbulent Years: A History of the American Worker, 1933-1941 (1970), the most thorough labor history

- Bernstein, Michael A. The Great Depression: Delayed Recovery and Economic Change in America, 1929-1939 (1989)

- Best, Gary Dean. The Nickel and Dime Decade: American Popular Culture during the 1930s. (1993) online edition

- Best, Gary Dean. Pride, Prejudice, and Politics: Roosevelt Versus Recovery, 1933-1938 (1991), conservative critique

- Blumberg Barbara. The New Deal and the Unemployed: The View from New York City (1977).

- Bordo, Michael D., Claudia Goldin, and Eugene N. White, eds., The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century (1998). Advanced economic history.

- Bremer William W. "Along the American Way: The New Deal's Work Relief Programs for the Unemployed." Journal of American History 62 (December 1975): 636-652 online in JSTOR

- Chandler, Lester. America's Greatest Depression (1970). overview by economic historian.

- Fisher, Irving. "The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions," Econometrica, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Oct., 1933), pp. 337–357 in JSTOR

- Friedman, Milton and Anna J. Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960 (1963), classic monetarist explanation; highly statistical; partly reprinted as The Great Contraction. excerpt and text search

- Gallaway, Lowell, Richard Vedder, Martin Bronfenbrenner. Out of Work: Unemployment and Government in Twentieth-Century America 336 pp online edition, by conservative economists

- Grant, Michael Johnston. Down and Out on the Family Farm: Rural Rehabilitation in the Great Plains, 1929-1945 (2002)

- Hapke, Laura. Daughters of the Great Depression: Women, Work, and Fiction in the American 1930s (1997) excerpt and text search

- Himmelberg; Robert F. ed The Great Depression and the New Deal (2001), short overview

- Howard, Donald S. The WPA and Federal Relief Policy (1943) online edition

- Jensen, Richard J. "The Causes and Cures of Unemployment in the Great Depression," Journal of Interdisciplinary History 19 (1989) 553–83. online at JSTOR

- Kennedy, David. Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (1999), wide-ranging survey by leading scholar; online edition

- Klein, Maury. Rainbow's End: The Crash of 1929 (2001) by economic historian excerpt and text search

- Kubik, Paul J. "Federal Reserve Policy during the Great Depression: The Impact of Interwar Attitudes regarding Consumption and Consumer Credit" Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. 30, 1996

- McElvaine Robert S. The Great Depression 2nd ed (1993) social history

- Mitchell, Broadus. Depression Decade: From New Era through New Deal, 1929-1941 (1964), overview of economic history online edition

- Parker, Randall E. Reflections on the Great Depression (2002) interviews with 11 leading economists

- Roose, Kenneth D. "The Recession of 1937-38" Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Jun., 1948), pp. 239–248 online in JSTOR

- Romasco Albert U. "Hoover-Roosevelt and the Great Depression: A Historiographic Inquiry into a Perennial Comparison." In John Braeman, Robert H. Bremner and David Brody, eds. The New Deal: The National Level (1973) v 1 pp 3–26.

- Romer, Christina D. "The Nation in Depression," The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 7, No. 2. (Spring, 1993), pp. 19–39. major survey by leading economist, with comparisons to other nations in JSTOR

- Romer, Christina D. "What Ended the Great Depression?" The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 52, No. 4 (Dec., 1992), pp. 757–784 in JSTOR

- Romer, Christina D. "The Great Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 105, No. 3 (Aug., 1990), pp. 597–624 in JSTOR

- Rosen, Elliot A. Roosevelt, the Great Depression, and the Economics of Recovery (2005) argues productivity gains were more responsible for long-term recovery than New Deal

- Rothbard, Murray N. America's Great Depression (1963), by leading libertarian economist

- Saloutos, Theodore. The American Farmer and the New Deal (1982).

- Shlaes, Amity. The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression (2007), 480pp, popular history by journalist

- Singleton, Jeff. The American Dole: Unemployment Relief and the Welfare State in the Great Depression (2000) excerpt and text search

- Sitkoff, Harvard. A New Deal for Blacks (1978).

- Smiley, Gene. Rethinking the Great Depression (2002), conservative economist blames Federal Reserve and gold standard excerpt and text search

- Smith, Jason Scott. Building New Deal Liberalism: The Political Economy of Public Works, 1933-1956 (2005).

- Sterner, Richard. The Negro's share: a study of income, consumption, housing, and public assistance (1943), statistical analysis of 1930s ACLS E-book

- Sternsher, Bernard ed., Hitting Home: The Great Depression in Town and Country (1970), readings on local history

- Szostak, Rick. Technological Innovation and the Great Depression (1995)

- Temin; Peter. Did Monetary Forces Cause the Great Depression (1976)

- Tindall George B. The Emergence of the New South, 1915-1945 (1967). History of entire region by leading scholar

- Trout Charles H. Boston, the Great Depression, and the New Deal (1977)

- Warren, Harris Gaylord. Herbert Hoover and the Great Depression (1959).

- Watkins, T. H. The Great Depression: America in the 1930s. (1993). excerpt and text search

- Wheeler, Mark, ed. The Economics of the Great Depression (1998)

- White, Eugene N. "The Stock Market Boom and Crash of 1929 Revisited," The Journal of Economic Perspectives Vol. 4, No. 2 (Spring, 1990), pp. 67–83, evaluates different theories in JSTOR

- Wicker, Elmus. The Banking Panics of the Great Depression 1996 online review

- Wecter, Dixon. The Age of the Great Depression, 1929-1941. (1948). social history

Primary sources[edit]

- Bakke E. Wright. The Unemployed Worker: A Study of the Task of Making a Living without a Job. (1940).

- Cantril, Hadley and Mildred Strunk, eds. Public Opinion, 1935-1946 (1951), massive compilation of many public opinion polls online edition

- Lowitt, Richard and Beardsley Maurice, eds. One Third of a Nation: Lorena Hickock Reports on the Great Depression (1981) secret reports sent to Hopkins; excerpt and text search

- Lynd Robert S., and Helen M. Lynd. Middletown in Transition. 1937. sociological study of Muncie, Indiana

- McElvaine, Robert S. Down & out in the Great Depression: Letters from the "Forgotten Man" (1983); letters to Harry Hopkins; online edition

- Sterner, Richard. The Negro's share: a study of income, consumption, housing, and public assistance (1943), statistical analysis of 1930s ACLS E-book

Bibliography: World[edit]

- Aldcroft, Derek H. Europe's Third World: The European Periphery in the Interwar Years (2006) 217pp; ISBN 0-7546-0599-X. excerpt and text search

- Ambrosius, G. and W. Hubbard, A Social and Economic History of Twentieth-Century Europe (1989)

- Bernanke, Ben S. "The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach," Journal of Money, Credit & Banking, Vol. 27, 1995 online edition

- Brendon, Piers. The Dark Valley: A Panorama of the 1930s (2000), 816pp popular history of conditions worldwide. excerpt and text search

- Brown, Ian. The Economies of Africa and Asia in the inter-war depression (1989)

- Davis, Joseph S., The World Between the Wars, 1919-39: An Economist's View (1974)

- Dimsdale, Nicholas H.; Horsewood, Nicholas; and Riel, Arthur Van. "Unemployment in Interwar Germany: an Analysis of the Labor Market, 1927-1936." Journal of Economic History 2006 66(3): 778–808. Issn: 0022-0507

- Feinstein. Charles H. et al. The European economy between the wars (1997) excerpt and text search

- Garraty, John A. The Great Depression: An Inquiry into the causes, course, and Consequences of the Worldwide Depression of the Nineteen-Thirties, as Seen by Contemporaries and in Light of History (1986)

- Garraty John A. Unemployment in History: Economic Thought and Public Policy (1978)

- Garside, William R. Capitalism in crisis: international responses to the Great Depression (1993) excerpt and text search

- Haberler, Gottfried. The world economy, money, and the great depression 1919-1939 (1976), by leading older economist

- Hall Thomas E. and J. David Ferguson. The Great Depression: An International Disaster of Perverse Economic Policies (1998) excerpt and text search

- Kaiser, David E. Economic diplomacy and the origins of the Second World War: Germany, Britain, France and Eastern Europe, 1930-1939 (1980)

- Kindleberger, Charles P. The World in Depression, 1929-1939 (1986) excerpt and text search

- League of Nations, World Economic Survey 1932-33 (1934)

- Loh, Kah Seng. "New Winds in Economic History? A Look at Writings on the Great Depression in Southeast Asia." Crossroads 2006 17(2): 66–92. Issn: 0741-2037

- Madsen, Jakob B. "Trade Barriers and the Collapse of World Trade during the Great Depression"' Southern Economic Journal, Vol. 67, 2001 in JSTOR

- Madsen, Jakob B. "The Length and the Depth of the Great Depression: an International Comparison." Research in Economic History 2004 22: 239–288. Issn: 0363-3268

- Mundell, R. A. "A Reconsideration of the Twentieth Century' "The American Economic Review" Vol. 90, No. 3 (Jun., 2000), pp. 327–340 in JSTOR

- Romer, Christina D. "The Nation in Depression," The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 7, No. 2. (Spring, 1993), pp. 19–39. major survey by leading economist, with comparisons to other nations in JSTOR

- Rothermund, Dietmar. The Global Impact of the Great Depression (1996)

- Shiroyama, Tomoko. China during the Great Depression: Market, State, and the World Economy, 1929-1937 (2008)

- Temin, Peter. Lessons from the Great Depression (1991) 211pp; excerpt and text search

- Tipton, F. and R. Aldrich, An Economic and Social History of Europe, 1890–1939 (1987)

- Tooze, Adam. The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy (2007), highly influential new study

External links[edit]

- An Overview of the Great Depression from EH.NET by Randall Parker.

References[edit]

- ↑ The Great Depression According to Milton Friedman

- ↑ An Interview With Milton Friedman - Right Wing News (Conservative News and Views)

- ↑ "...government efforts -- first under Hoover and then under FDR -- to prop up wages despite falling prices led to a full decade of double-digit unemployment" The Politically Incorrect Guide to the Great Depression and the New Deal

- ↑ http://www.fff.org/freedom/0891a.asp

- ↑ Charles Kindleberger, The World in Depression 1929-1939 (1986), p 170

External links[edit]

- "The Great Depression Revisited," by Roger Garrison

- Great Depression

- "Regime Uncertainty: Why the Great Depression Lasted So Long and Why Prosperity Resumed after the War," by Robert Higgs

- "Reflections on Reflections: A Consensus about the Great Depression?," by Roger Garrison

- America's Great Depression, by Murray Rothbard

- "The Mythology of Roosevelt and the New Deal," by Robert Higgs

- Depression, War and Cold War, by Robert Higgs

- "Prophet of the Great Depression: Ludwig von Mises," by Frank Shostak

- "Review of The Political Economy of the New Deal, by Jim F. Couch and William F. Shughart II", reviewed by Gene Smiley

- "Wartime Prosperity?", by Robert Higgs

- "Our Economic Past: When the Government Took Over U.S. Investment," by Robert Higgs

Categories: [Great Depression] [New Deal] [Economic History] [Business] [Finance]

↧ Download as ZWI file | Last modified: 03/10/2023 16:13:12 | 301 views

☰ Source: https://www.conservapedia.com/Great_Depression | License: CC BY-SA 3.0

ZWI signed:

ZWI signed:

KSF

KSF